Olympic Throwback: When South Africa Soared to Olympic Gold in Athens 400 Freestyle Relay

When South Africa Soared to Olympic Gold in Athens 400 Freestyle Relay

In Swimming World’s latest Olympic flashback, attention is paid to the 2004 breakthrough triumph of South Africa in the 400 freestyle relay. The victory arrived on August 15, 2004 at the Athens Games.

As they walked to the blocks, there was a sense something special was about to unfold. They knew their moment was imminent, a mere three-plus minutes from coming to fruition. Never mind that a trawl through the past declared them to be an underdog. This foursome had a business appointment with history.

Prior to the 2004 Games in Athens, the 400-meter freestyle relay had been contested on eight occasions in Olympic competition. The first seven times the race was held, the United States captured the gold medal. In 2000, with the Games set in Sydney, Australia used its home-pool advantage, and a raucous crowd of 17,000 supporters, to put an end to the American streak.

As the Athens Games neared, the United States again held favorite status, Swimming World predicting the Americans to finish ahead of Italy. The Aussies were picked to finish fourth, although a caveat noted that if certain injuries healed – notably the back and shoulder of Michael Klim – Australia would certainly factor into the medals chase.

Predicted to earn the bronze medal was South Africa. Boasting a squad powered by internationally experienced veterans Roland Schoeman and Ryk Neethling, South Africa certainly belonged in the medals discussion. But the leap from a lower step on the podium to the top is far from easy, and nothing could go wrong for the South Africans if they were to pull off an upset on the second night of action.

“As we got closer to Athens, we knew that if every swimmer did what they were capable of doing, then we would be close to a world record,” Neethling said. “Whoever beats us would have to be at their absolute best. We never once spoke about medals. Just focusing on the process took a lot of pressure off us at the time.”

Photo Courtesy:

South African swimming has long produced world-class athletes, the likes of Karen Muir in the 1960s and Jonty Skinner in the 1970s registering world-record performances. A glance at the Olympic record book, however, will not reveal the names of Muir or Skinner or any other South Africans, for that matter, from 1964 through 1988. The problem? South Africa operated under apartheid, a racial segregation policy in which the white minority dominated politically, socially and economically.

Although apartheid was instituted in 1948, the practice did not affect South Africa’s Olympic participation until 1964, when the International Olympic Committee announced it would ban the nation unless it publicly denounced racial discrimination. When South Africa failed to condemn apartheid, even following a last-chance, 50-day window, the IOC banned the country from Olympic participation.

Muir and Skinner were affected the most by the ban and received a closeup view of how politics and sports have often shared a contentious relationship. Despite setting numerous world records during her career in the 100 and 200 backstroke events, Muir never got to prove herself on the biggest stage in her sport. As for Skinner, he would have been a contender for gold in the 100 freestyle at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, where American Jim Montgomery set a world record of 49.99 to become the first man in history to break the 50-second barrier in the event. To prove just how formidable a contender he would have been, Skinner broke Montgomery’s world record three weeks later, the South African clocking 49.44 while racing at the Amateur Athletic Union Championships in Philadelphia.

South Africa’s ban from the Olympics lasted through the 1988 Games in Seoul. In June 1991, however, South African Parliament repealed key apartheid statutes and, one month later, the IOC welcomed the country back into the Olympic family for the 1992 Games in Barcelona. South Africa won two silver medals in Spain, Elana Meyer finishing second in the women’s 10,000-meter run and Wayne Ferreira and Piet Norval claiming second place in the men’s tennis doubles competition.

Between the 1996 and 2000 Olympics, South Africa added 10 medals, half of which were won by swimmers. In 1996 in Atlanta, Penny Heyns doubled as champion of the 100 breaststroke and 200 breaststroke while Marianne Kriel earned bronze in the 100 backstroke. Four years later in Sydney, Heyns picked up a bronze medal in the 100 breaststroke, with Terence Parkin securing a silver medal in the 200 breaststroke.

Those efforts in the pool served as table-setters for 2004.

The status of minor-medal contender might have been the prevailing prediction for South Africa in the 400 free relay in Athens. In the minds of Schoeman and Neethling, though, the gold medal was within reach. The confidence of the team’s veterans permeated to Lyndon Ferns and Darian Townsend. Given the pressure-filled atmosphere of every Olympiad, having the junior members of the squad envision the ultimate result – and believe in its attainability – was imperative.

The fact that South Africa remained optimistic about its hopes was a testament to the inner confidence possessed by the team’s members. At the 2003 World Championships, South Africa – using the same squad it brought to Athens – finished eighth in the final of the 400 freestyle relay. The team was more than four seconds off the pace set by Russia and finished nearly two seconds behind seventh-place Canada. It was not an effort reflective of the team’s potential, and that shortcoming percolated for the months ahead.

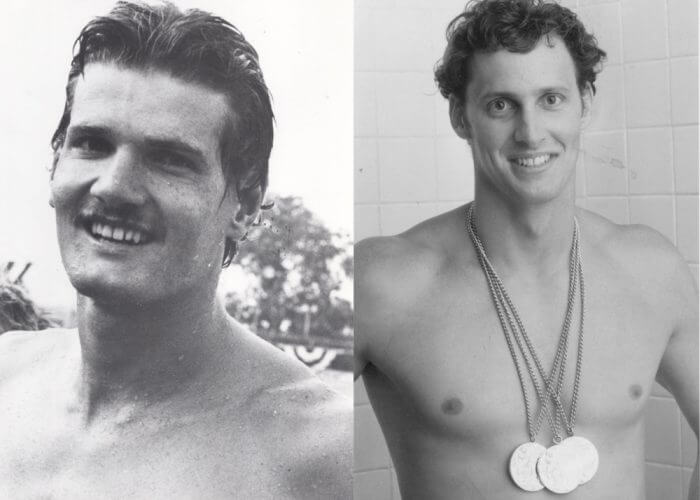

Ryk Neethling

“It was painful and embarrassing,” Neethling said of the World Champs finish. “We knew that we had the manpower to be more competitive, but we couldn’t put it together. We had our excuses ready: No money. No sponsors. No coaches with us. The usual South African struggles. We had to put the excuses behind us. From Barcelona, it was all about supporting each other, knowing full well that we still had to race individually but we believed that we could achieve a lot more as a team than as individuals. This wasn’t just lip service or feel-good mumbo jumbo. We really lived this daily and encouraged each other in every session. We truly became like brothers.”

Aside from representing South Africa, there was a connection between Schoeman, Neethling and Ferns, as all competed collegiately for the University of Arizona, where they were coached by Frank Busch and Rick DeMont. There was overlap between Schoeman and Neethling in Wildcat suits, with Ferns hitting campus a little later. Still, they all were coached by Busch and his right-hand man, DeMont, as they prepared for Athens, and their daily practice battles sharpened their skills ahead of the most important meet of their careers.

Schoeman and Neethling had to stymie a rivalry that brewed between them. While Schoeman was always a pure sprinter, Neethling was better known for his distance-freestyle abilities in the early portion of his career. Eventually, he shifted his focus down to the shorter distances, which meant clashes with Schoeman. To their credit, Schoeman and Neethling were able to put their fierce rivalry aside for the betterment of team and country.

Ferns’ biggest contribution was the confidence he supplied from a performance in late 2003. Racing at the Texas Invitational, Ferns posted a time of 48.9 in the 100 freestyle, a significant leap from a previous best of 50-low. Because they were training with Ferns, Schoeman and Neethling knew the work they were putting in was being rewarded.

Townsend, meanwhile, was younger than his compatriots but armed with talent and on the path to a sterling career. Originally an athlete at the University of Florida, Townsend eventually transferred to the University of Arizona, following the road mapped out by Schoeman, Neethling and Ferns. But for the summer of 2004, all that mattered was coming through with an admirable contribution, specifically a leg that wouldn’t doom South Africa’s chances.

It became immediately clear that each member of South Africa’s relay was ready to shine, even if there were still a few hurdles to clear. There is a lengthy history of tumult between Swimming South Africa, the governing body of the sport in the nation, and its top athletes. While other countries substantially fund their premier swimmers, Swimming South Africa has been known to force its swimmers to pay for airfare to international competitions, and come up short on promised rewards, including financial bonuses.

Lyndon Ferns

Prior to Athens, Swimming South Africa officials promised that DeMont, based on his work with the headliners of the team, would have a deck pass and accommodations close to the pool. Upon arrival, DeMont had neither and some running around was necessary to get him situated. Through connections, DeMont ultimately received a deck pass via Venezuela, a move that allowed him to properly coach the relay.

To preserve energy, it is commonplace in relay events for countries to swim a team in the preliminary heats that will undergo a change for the final. The United States only returned one athlete, Neil Walker, from its prelim squad for the final. Australia subbed in two fresh swimmers. South Africa went with its Big Four in prelims, the quartet clocking 3:13.84 to take the top seed for the final and missing the world record by just .17. Perhaps most important, the South Africans’ already brimming confidence received an extra boost.

“It was tough keeping it together after the heats,” Neethling said. “We knew we still had a little bit left in us for the finals but also knew that the Aussies, Russians and Americans would come with new, fresh teams. Once we got to the Olympic Village, we tried to get some rest, but it was tough to relax. We could really feel that we were close to something special.”

The original plan was for South Africa to rest Neethling during the preliminaries, since the veteran was scheduled to compete in the 200 freestyle, an event dubbed the Race of the Century due to its showdown between Aussie Ian Thorpe, the Netherlands’ Pieter van den Hoogenband and American Michael Phelps. A few days ahead of the Athens Games, South Africa conducted a time trial in which Eugene Botes, Gerhard Zanberg and Karl Thaning were given the chance to earn a prelim position on the relay. But after none of the swimmers produced a satisfactory performance, South Africa couldn’t risk sitting Neethling and missing the final. As a result, Neethling scratched the 200 free and went to work in the prelims of the relay.

After qualifying second behind South Africa during the morning, Team USA head coach Eddie Reese and his staff had to decide on the lineup for the final. As the first- and second-place finishers from the United States Trials, Jason Lezak and Ian Crocker were locks. By virtue of posting the fastest split of the prelims, Walker earned his spot. The fourth position came down to Olympic stalwart Gary Hall Jr., a proven relay contributor and reigning Olympic champion in the 50 freestyle, and Phelps, who had become the face of the sport and was chasing eight medals in Athens. The problem with Phelps was his lack of experience and track record in the 100 free. As talented as he was, Phelps wasn’t a sprinter, so the staff determined if two of the Americans in the prelims raced faster than 48.3, Phelps’ time from earlier in the year, then Phelps would be displaced.

Only Walker managed to clock in under 48.3 and, ultimately, Reese and his assistant coaches chose Phelps, a decision that – to put it mildly – irked Hall. Rather than sit back, Hall was vocal about the decision. Journalists covering the Games did not miss the opportunity to let the veteran vent and express his views.

“I felt like I had egg on my face,” Hall said. “I very much wanted to be part of the relay that reclaimed that medal. There were no exceptions for anyone else. No one qualified for the Olympic Team in February except Michael Phelps.”

Regardless of Hall’s displeasure with Reese’s coaching, the final of the 400 freestyle relay went off without him. Really, with the way Schoeman jumpstarted the South Africans on the leadoff leg, the race went off without any type of challenge.

Covering the opening leg in 48.17, Schoeman promptly gave South Africa a .99 edge on Italy and a 1.20-second margin over Russia. How about the United States? Well, Crocker’s leadoff leg was a disaster, as the American touched in 50.05 to finish nearly two seconds behind Schoeman and, for all intents and purposes, eliminate the United States from gold-medal contention.

It was later revealed that Crocker had been battling a sore throat prior to the start of the Games. But Reese, Crocker’s coach at the University of Texas, felt his athlete had earned his slot on the relay at Trials, and wasn’t going to remove him from relay duty.

With clean water in front of him, Ferns was superb as the follow-up to Schoeman. Ferns delivered the fastest split (48.13) of any of the second-leg swimmers and, by that point, South Africa was basically in coronation mode.

“After seeing the size of the leadoff I’d gotten, I knew we were in with a great shot,” Schoeman said. “Lyndon was an absolute beast in the water. We’d spoke a lot about this moment and how we would handle it. He was out fast and kept the lead.”

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

After Ferns maintained South Africa’s edge, Townsend checked in with a split of 48.96 for the third leg, allowing Neethling to cap his country’s gold-medal triumph in grand fashion, a split of 47.91 doing the job. South Africa’s time of 3:13.17 not only provided a 1.19-second margin of victory over the Netherlands, it slashed exactly a half-second off Australia’s world record of 3:13.67, set at the Sydney Games.

The Netherlands’ surprise silver medal was the result of van den Hoogenband anchoring his team in 46.79, the fastest split in the field by more than a second. After Crocker’s nightmare start, the United States relied on Phelps, Walker and Lezak to rally for the bronze medal.

“This was our day,” Schoeman said after the race. “As the movie says, ‘Any Given Sunday.’ For the relay, I told the guys, this is our Sunday.”

Schoeman didn’t just propel South Africa to its first relay crown. The sprint star carried his momentum into the 50 freestyle and 100 freestyle, where he earned bronze and silver medals, respectively. Neethling just missed a medal in the 100 free, as he placed fourth. At the next year’s World Championships, Schoeman was the champion of the 50 freestyle and 50 butterfly and Neethling was the bronze medalist in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle. Ferns and Townsend also enjoyed sensational careers, NCAA titles dotting their resumes.

There is no doubt, though, that the Summer of 2004 remains the defining moment in South African swimming history. The success of that day in Athens allowed future Olympic champions Cameron van der Burgh and Chad Le Clos to chase their own gold medals.

“We believed we had a point to prove – to our country, to the world of swimming, but most importantly, to ourselves,” Schoeman said. “I believe it helped kickstart swimming again in South Africa. It had been quite a few years since any (male) swimmer in the country really had someone they could look up to, someone who had been successful internationally and could pave the way. We had Penny Heyns and Marianne Kriel, but no real world-beaters that the young men in South Africa could look up to. I also believe that evening helped unite South Africa. As a country, we have had a fair amount of challenges and we tend to focus a lot on our differences and past atrocities, and understandably so. On that night, we, like the rugby teams that won World Cups, allowed South Africans to celebrate what we have in common. It was a life-changing event in many ways, something that I’ll always remember.”

Neethling also remembers the moment with fondness and has used the events of Athens – confidence, defying odds and performing under pressure – to serve him in the business world. It isn’t unusual for someone to approach Neethling and recount where he was on the night South Africa struck gold.

Neethling also recognizes that the success found in that outdoor pool in the Greek capital was attained through the ultimate team effort, four guys pooling their talents to prevail over the best competition the world had to offer.

“It boggles my mind sometimes that we managed to get four guys from a small country like South Africa together to beat the rest of the world,” he said. “We were also the only team that swam the same four guys at night as the morning, and in the same order. I am thankful for my teammates, coaches and everybody that played a part in it, especially (Busch) and (DeMont). They believed in this dream when no South African coach or administrator did. I am thankful that I have a gold medal to show for all the hard work and sacrifice. A lot of people don’t get anything and come very close. I wouldn’t be where I am if it wasn’t for the whole experience. The race that changed my life.”

Great article. Well written.

Great nostalgic article, always great reading about the relay from the South African perspective leading up to that performance

But what about that Eddie Reese/Ian Crocker storyline eh? I would love to read more about what happened there from the US perspective as it seems Gary Hall was justified in his response about being left out of the relay squad.

This was a great group, obviously. And besides their impact on South African Swimming, they had impact on swimming in the state of Arizona, long beyond each of their collegiate careers in Tucson — and continuing..

I’m not sure when (if?) Neethling and Ferns finished their aquatic escapades in Arizona but Schoeman and then Townsend have had impact even up to this last year.

Memory can get foggy, but I seem to recall Schoeman was introduced to the state pre-college at the US Swimming Grand Prix meet in May of 1998 at Phoenix Swim Club. Roland was born on the 4th of July, 1980 and would have been 17, about to turn 18 and then be a freshman at UofA that fall. Gary Hall, Jr. was working to promote the sport and had convinced the bulk of the best sprinters in the country to come to the meet primarily so they could have a three round sprint down from 8 in a heat to 4 in a heat to 2 in a heat, obviously making a bigger deal out of each heat as they went. No one here had ever heard of the teenager from Africa, and, after having to talk his way into the field, it was quite a deal when he made it to the ‘Final.’

He continued on with varying levels of success through being on the SA Olympic team in London and the 2023 SA World Championship team(even after becoming an American citizen in 2022). He tried again this year but came up short, though his Season Best :22.77 would have been fast enough to qualify for the US Trials (:22.79 cut) at age 43, nearly Gaby Rose-ish. He’s been at Phoenix Swim Club for multiple years now, where his 2004 teammate Darian Townsend has been the Head Coach for a few years, after coaching stops at other Arizona USA Swimming Clubs.

Darian’s Arizona aquatic experience has been long and rich, as well. After a year at Florida prior to Athens, Darian also came to UofA where he completed an excellent college career, including 2 individual NCAA titles (2007, 200 free; 2008, 200 IM). He continued to swim internationally for South Africa through 2012 and then, like Roland, became and American citizen(2014). Unlike Roland, Darian changed his Sport Citizenship as well and was on the US National team from 2014-2016(including 2014 SCM Worlds), announcing his retirement from open competition in 2017. He’d also been dabbling a bit in Masters meets and by then already held 25 Master’s World Records.

I found a podcast he did with Josh Davis in which he described his YouTube highlight (aside from Athens, of course), and it was really cool. On the World Cup circuit in Berlin after the 2009 Rome Worlds, he swam a 200 SCM IM next to Michael P. Darian, in one race, (which happened to be the SCM version of Michael’s 4-peat Olympic event) Darian beat MP by over 2 seconds (1:51.55 – 1:53.72) and broke Ryan Lochte’s WR (1:51.55 v 1:51.56). Third was Chad LeClos, 3 years out from his London 200 Fly Gold.