When She Beat the Boys: Celebrating Anniversary of Gertrude Ederle’s Historic English Channel Crossing

When She Beat the Boys: Celebrating Anniversary of Gertrude Ederle’s Historic English Channel Crossing

Today leaves us six years shy of the centenary of Getrude Ederle’s pioneering swim across the English Channel as the first woman to conquer the most famous stretch of open water in the world, courtesy of traction, Captain Matthew Webb and all that.

Ninety four years ago, 19-year-old Gertrude Ederle took to the waters at Cap Gris-Nez, France, and set off to the other side in England. She would come ashore at Kingsdown in Kent, the Garden of England, 14 hours and 39 minutes later. The official distance: 21 miles – except the rough seas always makes it more and for Ederle, winner of relay gold and two bronze medals over 100m and 400m freestyle for the United States at the Paris Olympics two years before, rough water, the swell and wash meant 35 miles.

That meant something extraordinary had happened, an event that not so much dented as pulverised male pride: she set a World record for the Crossing, the standard having been held to that date by Enrique Tiraboschi. A woman: faster than a man. Imagine the twitching of whiskers, the tugging of beards, the pipes being extinguished by sharp intakes of breath, the monocles peering down at the messenger before a bellow of “don’t be a fool, boy! Sew faster than men they may but swim? Heavens, no!”

Well, Trudy proved ’em wrong. Indeed, she set out to do just that. Later in life, she would say: “People said women couldn’t swim the Channel, but I proved they could.” She was to be taken seriously – after all, none of the five men who held the Channel record from 1875 to 1923 had got close to the speed she mustered this day 94 years ago.

Ederle grew up in New York City as one of four daughters and two sons of Henry Ederle, a butcher and provisioner, and his wife, Anna. Her father owned a summer cottage in Highlands, N.J., and she learned to swim on the Jersey Shore before beginning to train as a competitive swimmer at a time when women’s swimming was becoming ever-more popular on the back of pathfinders such as Australians Annette Kellerman and the first Olympic swim champion among women, Fanny Durack.

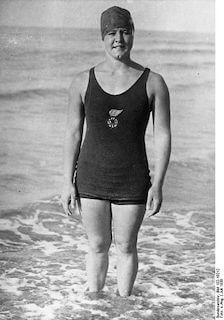

If Kellerman invented a skimpy black bodysuit that made it possible for women to swim unimpeded by frocks and helped to save a great many lives, Ederle was a leading light in a generation that promoted the streamlining of women’s suits. She wasn’t afraid to grease up for the fight either: she swam across the Channel coated in lanolin and sheep grease to help her stay warm and to protect her from jellyfish stings.

Photo Courtesy:

In 1919, Gertrude “Trudy” Ederle, aged 13 years and 9 months, became the first official world record holder over 880yd, in 13:19.0. She swam the time in a 110-yard pool in Indianapolis and it would be six years before her standard would be surpassed. Ederle was the first woman to hold all the world freestyle records from 100m to 800m. In a single swim at Brighton Beach, New York, in 1922, she set seven world records, from 100yd to 500m. In June 1923, she set a world record of 1:12.8 in the 100m freestyle and arrived in Paris for the 1924 Olympics tipped to win three gold medals.

Two of her teammates and rivals in the sprint freestyle had other ideas. In the first heat, two days before the final, Mariechen Wehselau broke the world record in 1:12.2. The next heat saw Ethel Lackie match Ederle’s best, at 1:12.8, and in the third heat Ederle stopped the clock at 1:12.6. In the final, Wehselau turned in 32.4, a touch ahead of Lackie, and both came home stroke for stroke. But it was Lackie who got her hand to the wall first, in 1:12.4, to Wehselau’s 1:12.8, with Ederle on 1:14.2 for bronze. In fourth, Constance Jeans (GBR), matched the placing she had earned four years earlier in Antwerp, despite a seven-second improvement in her personal best. Lackie was coached by Bill Bacharach, who had two other solo champions in Paris: Johnny Weissmuller (100m and 400m freestyle) and Robert Skelton (200m breaststroke).

For Ederle, the race meant a second bronze medal: five days earlier she finished behind teammates Martha Norelius and Helen Wainwright in the 400m. But she did take home a gold medal – as a member of the 4x100m relay with Lackie, Wehselau and Euphrasia Donnelly – and a new ambition: to become the first woman to swim the English Channel. Not only did she achieve this goal, she did so in a time almost two hours faster than the world record held by a man. Two million people greeted her with a ticker-tape parade through the streets of New York, where Mayor Walker likened her achievement to Moses parting the Red Sea and Caesar crossing the Rubicon. Ederle brought swimming to box-office status in the “Golden Age of Sport.”

Greeted By A Ticker-Tape Parade Of 2-Million Folk

Back to 1926 and upon arrival home from England and her great accomplishment, Ederle was greeted with a ticker-tape parade and an estimated two million people turned out to honour her. Her story is well told in “The Great Swim“.

Ederle was called “America’s best girl” by President Calvin Coolidge after her great swim of 1926. He invited her to the White House and told her: “I am amazed that a woman of your small stature should be able to swim the English Channel.” Ederle actually weighed 142 pounds and would become an adviser to a manufacturer of dresses for larger women.

Photo Courtesy:

She became a symbol of the Roaring 20’s, a decade that lauded heroics as much as materialism. For a while, she rated in the American public’s affection on a par with Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Bill Tilden and Red Grange.

Ederle had another name for herself: “water baby”. She often said that she was “happiest between the waves”. So much so that they couldn’t stop her: not even a post-measles hearing problem at five that had doctors telling her parents ‘no swimming’ could keep her from her element. She’d later says:

“The doctors told me my hearing would get worse if I continued swimming, but I loved the water so much, I just couldn’t stop.”

When famous after her swim, Ederle was invited to join a touring vaudeville act at up to $3,000 a week but it didn’t last, the doctor having been close to the mark on her hearing. She would later say of a short Hollywood stint: “I finally got the shakes. I was just a bundle of nerves. I had to quit the tour and I was stone deaf.”

In 1929, she was about to become engaged when she told the suitor that it might be difficult being married to a woman with poor hearing. He agreed – and scarpered. Later, Ederle recalled: “There never was anyone else. I just didn’t want to get hurt again.”

It came to good: for many years, Ederle taught swimming to children at the Lexington School for the Deaf in New York.

Paris To The French Coast & On To England

If medals over 100 and 400m hardly prepared her for the channel, her capability to cover the distance and endure was confirmed when she swam more than 16 miles through tough currents between the Battery and Sandy Hook, N.J. before Olympic selection.

In Paris in 1924, she raced with an injured knee and, together with the other female athletes from the United States, she had an added handicap of fatigue because of the five-hour trip from the hotel to pool each day. Were the hotels of Paris fully booked? No. United States officials felt the French capital city’s bohemian morality should be kept well away from the young ladies.

The Games done and dusted, she set about practising to do for women what Captain Webb had done for the blokes in 1875 over a staggering 21 hours 45 minutes.

Photo Courtesy:

Ederle first tried to swim the Channel in 1925. The Women’s Swimming Association provided financial backing but a mistake in the observation boat cost Ederle dear: after swimming 23 miles in 8 hours 43 minutes, the folk in the boat were not sure whether she had fallen unconscious. They prodded her to see – and those broke the rule: no touching. The attempt was over.

A perturbed Ederle insisted that she had not been drowning but resting. She felt embarrassed and later said: “All I could wonder was, ‘What will they think of me back in the States’?”

For her second attempt, she raised the $9,000 herself and with the help of her sister Margaret, she designed a two-piece bathing suit that “causes less drag in the water [but] be decent in case I failed and they had to drag me out.”

Shortly after 7 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1926, Ederle lined up on the shore at Cap Gris-Nez, a warning flag to small craft to avoid the choppy sea that day bristling on the breeze. “Please, God, help me,” is what she prayed, she would later recall. Beyond the strain, pain and gain, “Gertie”, as she was known to family, returned home to cheers of “trudy! Trudy! Trudy!”

At one point, the crowds were so excited to see her that she had to be rushed into Mayor Jimmy Walker’s office in City Hall. In the weeks that followed, someone even wrote a song titled prophetically: “Tell Me, Trudy, Who Is Going to Be the Lucky One?'” – for weeks on end she received proposals of marriage every day from men across the United States.

In 1933, she injured her back in an accident and was told she might never walk or swim again. She did both and in 1939 appeared in Billy Rose’s Aquacade at the New York World’s Fair.

Down the years, the anniversary of her swim has been celebrated many times but she once told The New York Times that she hated the reviews because they seemed too melancholy and apt to make her pitiable. In 1956, she told the newspaper: “Don’t weep for me, don’t write any sob stories.”

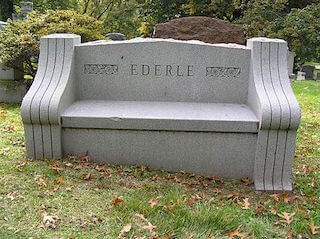

She died on November 30, 2003, in Wyckoff, New Jersey, at the age of 98 and was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City, a great innings done, Ederle and her legacy immortal.

why was it so important for Gertrude ederler’s siwn across the English channel was an important achievement