Great Races: When Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner Broke a Special Barrier – A Unique Summer Pursuit Of Sub-50

When Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner Chased Sub-50: A Unique Summer Pursuit

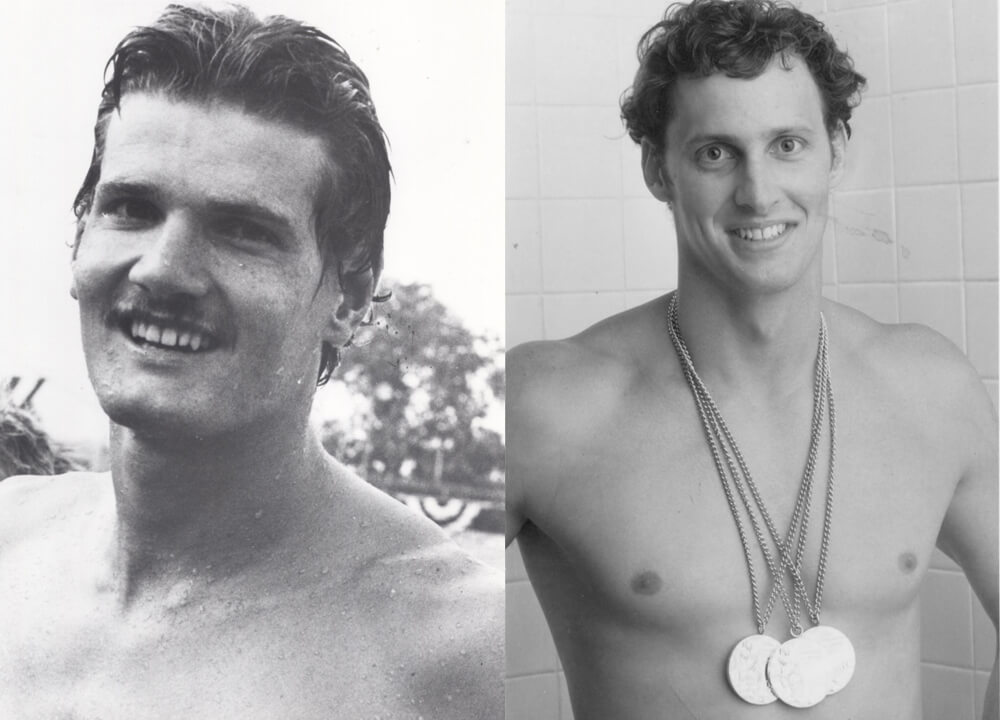

Swimming World’s Great Races Series has featured numerous duels between star athletes. In this edition, Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner engaged in a great race, albeit one in separate pools.

The most iconic barrier-breaking performance in sports history is not difficult to decipher. It is the 3:59.4 mile run by Great Britain’s Roger Bannister in 1954, marking the first time the four-minute threshold was eclipsed. The effort captured the attention of the world and opened the imagination of what was possible in an athletic endeavor.

Fourteen years later, American sprinter Jim Hines produced another legendary outing, as he became the first man to officially cover the 100-meter dash in under 10 seconds. The speed Hines displayed in 1968 handed him the gold medal in the event at the Olympic Games in Mexico City.

From the equine world, Secretariat is celebrated as the greatest racehorse of all-time and used the 1973 Kentucky Derby to put on a show that remains unmatched. Running 1:59.40 at Churchill Downs, Big Red – as he was known – became the first horse to crack the two-minute barrier in the Derby, which is run on a 11⁄4-mile track.

In the pool, breaching the 50-second barrier in the 100-meter freestyle became a major storyline of 1976. The men at the center of the chase, American Jim Montgomery and South African Jonty Skinner, never met during that Summer of Speed, as politics kept them apart. Nonetheless, they engaged in an entertaining, albeit long-distance, duel.

The 100 freestyle has long been considered swimming’s blue-ribbon event, and the territory of some of the sport’s legends. Duke Kahanamoku, Johnny Weissmuller, Don Schollander and Mark Spitz, to name a quartet, won Olympic gold in the two-lap discipline. More, Weissmuller was the first man to break the one-minute barrier, accomplishing the feat in 1922. Over the next half-century, the record continued to dip, to the point where sub-50 became a legitimate possibility midway through the 1970s.

In most eras, the Olympics bring together the best competitors an event has to offer. However, that was not the case at the 1976 Games in Montreal, where a key figure was missing from the pool deck. Four years before President Jimmy Carter infused politics into sports by leading a United States boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, politics played a role in the 1976 Games.

Due to its apartheid policies, South Africa was banned from the Olympic Games by the International Olympic Committee in 1964, a restriction that lasted until the 1992 Games. Caught in the middle of his country’s segregation practices, which he did not support, was Skinner, one of the world’s premier sprint freestylers.

Competing collegiately for the University of Alabama, Skinner established himself as an NCAA and United States national champion in the 100 freestyle. As much as Skinner might have been detached from his homeland and apartheid, his citizenship – based on IOC rule – made Skinner ineligible to compete on the biggest stage in sports. It was a hand Skinner was forced to accept, and it also dealt a blow to the depth of the 1976 Games. Without Skinner, Montgomery raced the clock, and not a rival who would have raised the level of competition.

As he prepared for the Montreal Games, Montgomery was a well-known commodity. In 1973, Montgomery flourished as a member of Team USA at the inaugural World Championships. In Belgrade, Yugoslavia, Montgomery earned gold medals in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle, and helped the United States win three relay titles.

Following the World Champs, Montgomery joined the power program of Indiana University, which was guided by Hall of Fame coach Doc Counsilman. As a Hoosier, Montgomery captured three individual NCAA titles and developed into an Olympian, thanks to Counsilman’s influence. Although Montgomery exhibited natural ability before working with Counsilman, the coach enabled Montgomery to hone his mental approach.

Jim Montgomery

Ahead of the Olympics in Montreal, Counsilman convinced the men’s team that it could establish itself as the greatest team in history. Indeed, that is what Team USA accomplished, as it won 12 of the 13 events and swept the podium in four disciplines.

“He’s the smartest guy I’ve ever known in my entire life,” Montgomery said of Counsilman. “Just sheer brain power. And he had a sense of humor. He just put it right on the plate. ‘We’re going to absolutely dominate. That’s my goal, and that’s my goal for you guys.’”

Montgomery personally accepted Counsilman’s challenge.

Coming off a bronze medal in the 100 freestyle from the 1975 World Championships, Montgomery elevated his performances in Montreal, a fact that was evident during the semifinals of the 100 freestyle. Erasing any doubt over who was the favorite for gold, Montgomery blistered a world record of 50.39, a mark which was nearly more than a second faster than the No. 2 seed, Italian Marcello Guarducci (51.35). Montgomery’s dominance allowed he and Counsilman to experiment in the final.

“After the prelims, we figured we had the race pretty much won,” Counsilman said. “So we risked it. We swam the race to break the record by going out harder. We figured that even if he died a little coming home, he’d still have enough to win.”

Montgomery and Counsilman were not just concerned with lowering the world record. The final was about taking Montgomery into – pardon the pun – uncharted waters. A sub-50 performance was within reach and producing a readout on the clock that started with a “4” was an enticing opportunity.

As a member of a squad that was obliterating the opposition, there was a competition within a competition of sorts for Team USA. Who could produce the most memorable performance? For that honor, the battle primarily came down to Montgomery and John Naber, the University of Southern California star who won the 100 backstroke and 200 backstroke events in world-record time. Montgomery, though, had the extra power of delivering a barrier-breaking outing.

The bronze medal Montgomery claimed in the 100 freestyle at the 1975 World Champs also served as motivation. During 1974 training, Montgomery and Counsilman toyed with a workload that was more geared toward the middle-distance events. Ultimately, it cost Montgomery some of his pop in his main event, but the error was better realized at the World Champs, rather than the Olympics. By the time Montreal called, Montgomery was in peak form and possessed lofty target times.

“I thought realistically I could swim 49.4 or 49.5,” Montgomery said. “I had some relay splits that were that fast at that time, and back then we didn’t have the fancy relay starts they do now. If I didn’t have that training failure in 1974, I wouldn’t have become Olympic champion. I was stronger and handled the power training necessary for the 100 free.”

The confidence brewed by Counsilman in Montgomery was clear from the start in the final as the 21-year-old bolted to the front of the field and held a half-body-length lead at the turn. Coming off the wall in 24.14, the question wasn’t whether Montgomery would win the race, but if he could join Bannister and Hines as a barrier breaker. Indeed, Montgomery was given access to the club by the slimmest of margins, the scoreboard flashing 49.99. Countryman Jack Babashoff followed in the silver-medal position, well behind in 50.81.

“This will put Montgomery in the Swimming Hall of Fame,” Counsilman said. “I think this is the last barrier in swimming. We broke one minute in the 100 freestyle 50 years ago, and I don’t think we are going to break 40 seconds. So this is it, at least for a long time. I thought it was the best swim of the Olympics, and we’ve had some good swims.”

Counsilman was prophetic in his statement, as Montgomery was enshrined into the International Swimming Hall of Fame as a member of the Class of 1986. While Montgomery’s profile obviously highlights his gold medal, it also references his barrier-breaking identity and place in history alongside Bannister.

Jonty Skinner – Photo Courtesy: Amelia B. Barton

As monumental as it was, Montgomery’s world record and solo status in the sub-50 club was short lived. Without the opportunity to race at the Olympics, Skinner identified the Amateur Athletic Union National Championships in Philadelphia as his focus meet for the summer. Scheduled for three weeks after the Olympics, the competition lacked the firepower present in Montreal, but Skinner wasn’t really racing the men in the adjacent lanes in Kelly Pool. Instead, Skinner was racing the clock and Montgomery.

Before settling on Philadelphia as the stage for his personal Olympics, an attempt was made to get Skinner American citizenship in time to compete at the United States Olympic Trials. A petition with more than 50,000 signatures was sent to Washington, D.C. and Representative Walter Flowers, a democrat from Alabama, introduced a bill to Congress – HR 12257 – that would award Skinner citizenship in time to compete at Trials. Alas, the push on Skinner’s behalf fell through, leaving him as a spectator to the Montreal Games.

“I really had no issues with not being there since I was focused on Philly,” Skinner said. “It ticked me off that (Montgomery) 50, and that is what fueled me the last few weeks getting ready. I had focused on breaking 50 as a season goal, so when (Montgomery) went 49.9, I adjusted to 49.8. I wasn’t nervous at all. I did a lot of visualization to prepare, so I was ready in my mind.”

Racing alone or without rivals to push the pace is not an easy chore, but Skinner had plenty of motivation. Despite besting the field by more than two seconds, Skinner relented. He went out in 23.83, .31 quicker than the split of Montgomery, and he came home slightly quicker as well. At the touch, Skinner produced a time of 49.44 to shave .55 off Montgomery’s performance from the Olympic Games.

Although an Olympic medal was not draped around Skinner’s neck, the moment was as meaningful. He had an opportunity taken from him for no fault of his own, but Skinner turned his situation into a positive. His world record was so impressive, it last nearly five years, until Rowdy Gaines clocked 49.36 in April 1981. As impressive, Skinner’s time would have won Olympic gold in 1980 and 1984 and would have earned the bronze medal at the 1988 and 1992 Games.

“Coach, I did it,” said Skinner to his coach at the University of Alabama, Don Gambril. “Since I couldn’t swim against (Montgomery), my opponent had to be the clock. I just kept telling myself, ‘This is your only chance. Don’t blow it.’”

Linked by the Summer of 1976, Montgomery and Skinner have remained involved in the sport in prominent ways. Montgomery followed his Olympiad by winning the silver medal in the 100 freestyle at the 1978 World Championships and, following a brief retirement, started training for the 1980 Olympic Trials, a pursuit that ended when the American boycott of the Moscow Games was announced. Montgomery eventually shifted into Masters competition and has operated swim clubs and swim schools.

As for Skinner, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1985, he took his skills in the water to the deck and a coaching career. Skinner served as the first coach of USA Swimming’s Resident National Team at the United States Olympic Training Center and later held the role of USA Swimming’s Director of Performance Science and Technology. The latter role is one he also held for British Swimming. Before retiring in 2020, Skinner returned to the college ranks, serving as an assistant coach for the University of Alabama, and then Indiana University.

“I could always talk from experience when it came to helping swimmers prepare for peak-level events,” Skinner said of the transition from elite athlete to coach. “I very rarely talked about (his world record in Philadelphia), but the athletes knew my background, so they trusted my opinions.”

Montgomery and Skinner each had his moment to shine, and history looks back favorably at each career. Montgomery will always have his Olympic gold medal. Skinner will always have his day, Aug. 14, 1976, as proof of overcoming disappointment and factors beyond one’s control. There is room to honor both men.

“The Olympics were one day, and this was another,” Skinner said. “But I hope Jim was watching me on TV.”

Madison East High School Grad Jim Montgomery!

great story of focus on beating the clock! not the politics…

a great story indeed; glad to have Jim as a fellow Masters swimmer and Jonty as a stroke technique mentor

Good case to be made for Jonty as the best sports person to ever come out of SA. Not allowed to compete internationally he had to make his own Olympics in Philadelphia. That 49.44 and the 5+ years it stood puts him up there with The Duke, Weismuller, Spitz, Popov and Hoogy.

And of course Biondi.

A great story about a great swimmer .But more than that a wonderful human being .Have not seen Jonty since we were team mates in 1971 .Wishing him good health and a happy retirement.

I am honored to have witnessed both of those great 100-meter swims … Jonty’s venue at Kelly Pool was old and shallow compared to Montreal’s state-of-the-art facility and when these two giants did finally come together to race it was a half-year later at the ’77 NCAA Champs in Cleveland. USC’s Joe Bottom broke the American record in prelims (43.49) setting up a big 3 race in the center of the pool, but it was outside smoker Dave Fairbank from Stanford who stole the spotlight in that much-ballyhooed 100-yard showdown (sorry that our divers’ room kept you awake that night before Jim!).

From the archives:

100‐Yard Freestyle Results 1, Dave Fairbank, Stanford, 43.68 seconds (American and N.C.A.A. record 43.49 by Joe Bottom, Southern California, in afternoon trials and NCAA record of 43.92 by Jonty Skinner, Alabama, 1975); 2, Jonty Skinner, Alabama, 43.94; 3, Jim Montgomery, Indiana, 44.05 4 Jack Babashoff, Alabama, 44.09; 5, Robert Sells, Tennessee, 44.10; 6, Joe Bottom, Southern California, 44.21; 7, John Ebuna, Tennessee, 44.37; 8, Rick DeMont, Arizona, 44.66; 9. Gary Schatz, Auburn, 44,67; 10, Rick Hartman, Auburn, 45.05; 11, John Newton, Tennessee, 45.13; 12, Jim Fairbank, California, 45.32.