Underappreciated, Don Schollander Was a Legend; And a Star During the First Tokyo Games

Underappreciated, Don Schollander Was a Legend; And a Star During the First Tokyo Games

How can a five-time Olympic champion be underappreciated? How can a man who set double-digit individual world records go overlooked? How can the one-time face of Team USA find himself snubbed on the scale of historical greatness?

By all measures, Don Schollander is a legend in the sport, a Hall of Fame talent who was unrivaled in his heyday. He was dominant. He was versatile. He was clutch in pressure situations. A half-century beyond retirement, he deserves continued recognition of his greatness. Yet, Schollander is a largely forgotten star, his impact lost to a combination of unfortunate timing and modern-day fascination.

Among aquatic enthusiasts, there is little debate regarding the greatest American triumvirate among male athletes. Michael Phelps sits at the head of the boardroom table, the CEO of the sport. Meanwhile, vice presidential status is held by Johnny Weissmuller, actually best known for his cinematic identity as Tarzan, and Mark Spitz, he of seven gold medals and seven world records at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich.

Because modernity plays a role in most subjective rankings, the next name typically mentioned is that of Matt Biondi, the highest-profile American star of the 1980s and 1990s. What about Schollander? While he was widely appreciated in his era, his greatness was quickly dismissed, the aura of Spitz casting an inescapable shadow.

Timing simply was not on Schollander’s side. His excellence was delivered prior to the period in which professionalism was an option, with endorsement deals available to the top-tier athletes in the sport. More, Schollander was the victim of Spitz’s surging star and monumental performance at the Munich Games.

Really, the lack of appreciation for Schollander is an injustice.

A Stellar Career

There are several ways to place the career of Don Schollander in perspective. The task could be handled by focusing on his Olympic exploits. Or, we could dissect the power of his world-record performances. Instead, let’s go with this bullet point on the man’s resume: Schollander was a member of the inaugural induction class into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

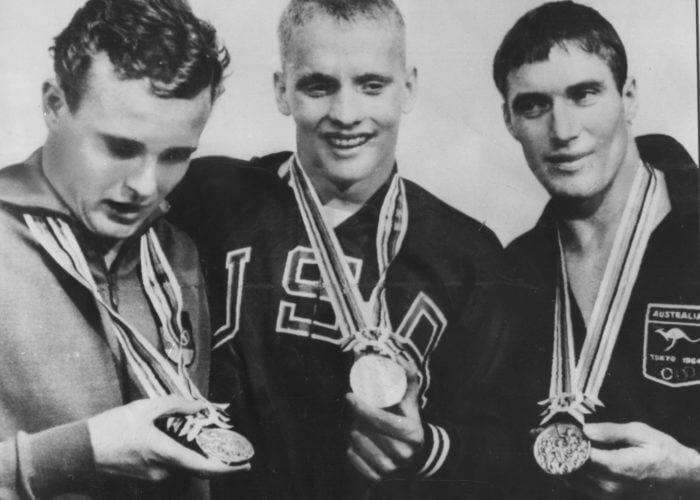

Schollander, only 18, matched what legendary track athlete, Jesse Owens, managed at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin: four gold medals. (Pictured, from left: 1964 men’s Olympic 400 freestyle medalists: Frank Wiegand, United Team of Germany, silver; Schollander, gold; and Allan Wood, Australia, bronze.)

When the Hall of Fame announced its initial entrants in 1965, Schollander was just a year removed from starring at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. He was also a mere 19 years old, with several more impressive years ahead of him. Yes, Schollander earned Hall of Fame status as a teenager and in the prime of his career.

Schollander’s precocious talent was on display in his early teens, as he guided Lake Oswego High School to the Oregon state championship as a freshman. Meanwhile, by the time he was 16, he was a multi-time national champion and on pace to become a headliner for the United States. That identity was etched at the 1964 Olympics.

Having qualified for the Tokyo Games in the 100 freestyle and 400 freestyle, Schollander embraced a four-event schedule. In relay action, Schollander fueled the United States to world records in the 400 freestyle relay and 800 freestyle relay, with Germany the runnerup in both events. His individual success required a bit more work but was just as golden.

In the 100 freestyle, Schollander (53.4) eked out a narrow triumph over Great Britain’s Bobby McGregor (53.5). A couple of days later, he went back to work in the 400 freestyle, this time prevailing with a world record of 4:12.2, more than two seconds clear of the silver-medal time of Germany’s Frank Wiegand (4:14.9). The critical nature of the 100 freestyle was not lost on Schollander, as that event jumpstarted his success and supplied much-needed momentum.

“Because it was my first event, I felt that this race could make me or break me for the rest of the Games,” he said. “If I won, I would be up for the rest of my events – my confidence would be flying high. If I lost, I would be down. That sounds temperamental, but I have seen an early race work this way on swimmers. So this 100 free took on much more importance than just another event.”

With four gold medals to his credit, Schollander became an Olympic hero, with his title count matching what the legendary track athlete, Jesse Owens, managed at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. The total could have been higher, too, if not for the U.S. coaching staff’s decision to not use Schollander on the 400 medley relay.

As the Olympic champion in the 100 freestyle, Schollander figured to have earned the anchor slot on the medley relay. Instead, the coaches went with Steve Clark, who was the fastest American in the 400 freestyle relay. The decision was highly questionable.

“Certainly, in the back of my mind, I was aware that this could mean my fifth gold medal,” Schollander said of being on the medley relay. “And it wouldn’t be just one more gold medal – it would be an unprecedented fifth gold medal. No swimmer had ever won four gold medals at an Olympics, but nobody in history – in any sport – had ever won five. But this wasn’t my arguing point. I felt that I had earned the spot on the medley relay team.”

In the ensuing years, Schollander added to his greatness, winning the 200 freestyle at the 1967 Pan American Games and adding Olympic gold in the 800 freestyle relay at the 1968 Games in Mexico City.

What Could Have Been?

The schedules utilized for today’s major championship competitions provide a little something for everyone. At the World Championships, sprint specialists are offered 50-meter events in each stroke. And at this summer’s Olympic Games in Tokyo, the 800 freestyle will be offered for men for the first time, with the 1500 freestyle new to the women’s program.

During Schollander’s era, the Olympic program was limited, and the World Championships were still a figment of the imagination. Specifically, Schollander was denied the chance to contest the 200 freestyle – his best event – when the American was at his peak at the 1964 Olympics.

Although he possessed the speed necessary to excel in the 100 freestyle and the endurance required of the 400 freestyle, Schollander was at his best in the 200 freestyle. It was his sweet spot and no foe had the ability to keep pace. A statistical look at the event serves as proof of Schollander’s dominance.

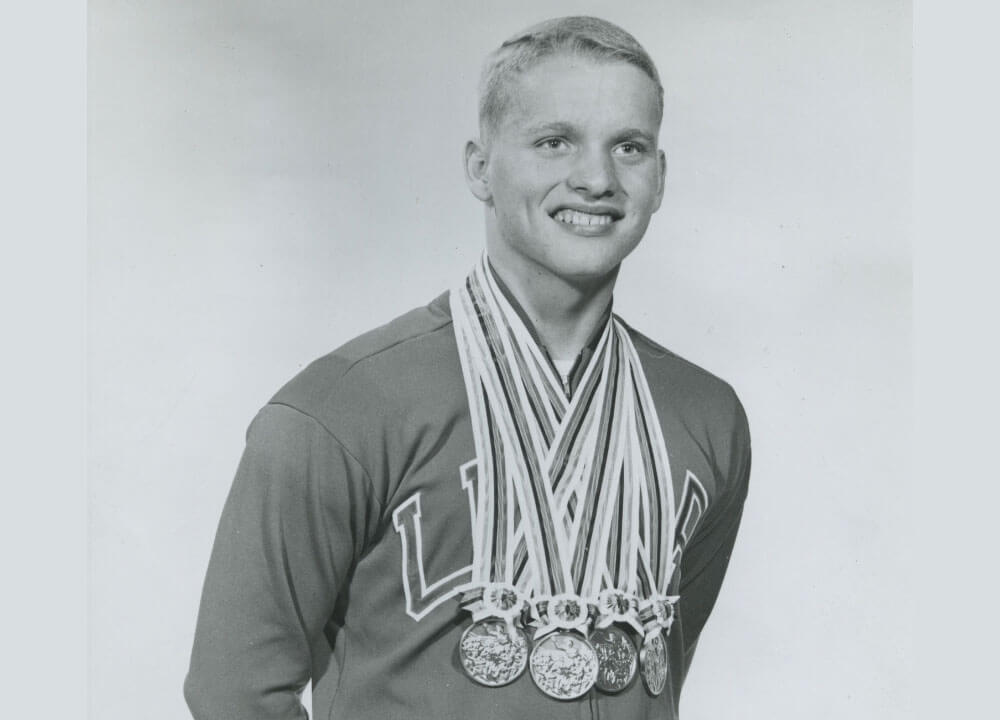

Don Schollander – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

From 1962 to 1968, Schollander set 11 world records in the 200 free, including seven consecutive marks from 1964 to 1968. Over the course of those records, Schollander took the time in the event from 2:00.4 to 1:54.3, a massive leap that speaks to the revolutionary nature of Schollander’s skill.

“There are three things that make Don such a terrific swimmer,” once said George Haines, who molded Schollander into a champion at the Santa Clara Swim Club. “First, he is almost flawless mechanically. Second, he has a tremendous desire to win. Finally, he is a thoroughly intelligent competitor with a wonderful tactical sense.”

As successful as Schollander was at the 1964 Olympics, his haul almost surely would have been five gold medals had the 200 freestyle been part of the program. But the four-lap discipline was not added to the schedule until 1968 and while Schollander was still superb at that point in his career, he was not the untouchable force who went to Tokyo and emerged as the sport’s main man.

At the Mexico City Games, Schollander claimed the silver medal in the 200 freestyle, beaten to the wall by Australian great Michael Wenden. It was a surprise setback, but one that Schollander took in stride and did not lament. Rather, he was able to view his career through a lens that focused on all that was accomplished, not what was lost.

“I feel very fortunate to have gained the success I’ve achieved,” he said. “I think it’s a career I’ll be able to look back on and be very pleased about. I would have liked to have won because it is my last race, but I did as fine a job as I could. I’m not disappointed a bit.”

A Cerebral Approach

One of the main struggles for swimmers who reach the pinnacle of their sport is finding an alternate identity. Athletes in the sport, including today, have a difficult time transitioning to life after swimming, or finding interests to offset the zoned-in nature of training. Schollander, though, was different.

After his Olympic success, Schollander enrolled at Yale University and continued to excel in the water. But as an introspective individual, he found a balance in his life and made sure he was well-rounded in his endeavors.

“This is the crux. Before you decide how you want to live your life, you must look at yourself and attempt to know yourself,” Schollander once said. “I look at myself as a person who’s trying to develop as an individual. It’s been important to me throughout my life to be much more than a student, to be much more than an athlete, to be much more than anything. This is consistent with my philosophy of the well-rounded, but not necessarily Renaissance, man. I’m proficient in the academic side, the athletic side and the social side. I’m not proficient in the arts – music, painting, sculpture. Unfortunately, I don’t have time to go to more plays, take in concerts. I’m always on the go. I think I have a very active mind. I don’t feel I do total justice to anything.”

Another element of Schollander’s career that defined his success was the mental game he played. Schollander walked with an air of confidence about him, and never appeared rattled. He played a psychological game with the opposition, his lack of nerves – well – unnerving.

Obviously, Schollander did justice to his career in the pool. Sure, the likes of Phelps, Spitz and Weissmuller might receive greater attention, but anyone with deep knowledge of the sport will recognize Don Schollander as a legend. He was a thoroughbred in the water, as once noted by his college coach, Phil Moriarty.

“His stroke is flawless,” Moriarty said. “Every other swimmer I’ve worked with had a flaw. With legs only, he does as well as anyone, and he has combined this so well with his stroke that he is a one-motored man. Many swimmers are two-motored, in that they don’t synchronize their stroke and kick. As a coach, all I can do is observe him and tell him when he’s going off pattern, keep him busy, give him a program. With Don Schollander I feel like I’m training a racehorse. How can I communicate with a horse?”

By letting him run, or in Schollander’s case, swim. And he performed his craft better than most.

Yay!!

He is the man, in swimming, that I looked up to…..and he made me want to be a better swimmer.

Schollander brought the spotlight to competitive swimming for the post WWII baby boom generation. I remember him on the cover of Life Magazine, a moment of well deserved national pride. His accomplishments were inspirational for me as a very average swimmer on a high school team in west Texas with several all-American swimmers. Doug Russell was one of those all-Americans. He came home from the ‘68 Mexico City Olympics with two gold medals including the 100 fly touching out Mark Spitz. Several teammates from those days have liked and commented on this article. Innocent times singing Beach Boys tunes with ukulele accompaniment on drives to swim meets. It seems like only yesterday …

He was my hero when I was a young swimmer.

Great swimmer and set the stage for multiple medal performances! It would have been good to see my good friend Ian Smith (formerly of South Africa) mix it up at the Olympics!

Yes perfect strike and great kick. If I remember correctly Shollander and Spits both kicked 56 or 57 for 100 yards in the kick board relay during the San Leandro Relay Onky Meet.

I swam on the Yale team with Don. He was far and away the best swimmer any of us had ever seen. Plus… a remarkable man, a true gentleman. I would like to know about Don now – and would be thrilled to see him at our Yale 55th (!!) reunion, coming up in just two more years.

Fred Bland, Yale 1968

(I’m still swimming, Don!)

Both Haines and Moriarity make reference, in your well resourced piece, to his flawless stroke. Schollander speaks of not being well versed in the arts; no, his was simply a different genre.

His stroke was art.

Many gave a portion of the credit in this regard to his development in Oregon under the tutelage of Walt Schlueter at Multnomah Aquatics before heading to Santa Clara. Schlueter was one of the founders of ASCA, its first Level 5 Certified Coach, and an inductee in the first ASCA Hall of Fame class in 2002.

I swim with Don in 1967 panamerican ganes and 1968 olimpics was amazing I lean his stroke with my coach Ronald Johnson

I was a young coach during his years of dominance. Not only a great athlete a better person. The lack of recognition can be blamed on USA Swimming, ASCA, ISCA not one of which view history as important. As a kid, like many of my friends, we knew ALL the baseball players. Most swimmers/Coaches know very little about the history of our fabulous sport!

Swam against Don many times!!! Maybe won race here and there. He is a very very nice guy!!

I had the pleasure of seeing him swim at Yale. He had the most beautiful stroke I have ever seen.