UK Sport Urged To ‘Review Values’ After ‘Tokyo Investment Principles’ Fail To Mention Olympic Sports Diversity

The Black Swimming Association in Britain has called on UK Sport to “immediately review its values and reconsider the power they have to make sports accessible and inclusive for everyone” after a report into Olympic sports diversity revealed heavy underrepresentation of Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups on the majority of sports squads at the Rio 2016 Games.

The report by Summus Sports notes that UK Sport – the umbrella body that decides what level of funding sports receive from the ring-fenced budget generated from the National Lottery for Olympic sports, made no mention of diversity or inclusion as a criteria or motivation in a nine-page Tokyo Investment Principles document.

That comes as no surprise in a realm in which medals on the biggest of occasions in sport, the Olympic Games at the peak, are the dominant driving force of funding, some ranked in the best 10 in the world going unfunded if their recent form includes places in finals at global level but no medal. As UK Sport states in its “Investment Principles”:

“Maximising the impact of sporting success by targeting investment at athletes and sports capable of winning medals …”

Olympic sports diversity planning appears to be uncoupled from elite funding handed out through sports federations, with many of the best-funded sports having fielded all-white teams at Rio 2016.

The Summus Sports report notes that in 16 out of 23 Olympic teams and eight out of 19 Paralympic squads comp[eting for Great Britain in Rio, there wasn’t a single BAMA athlete.

The issues stretch beyond ethnicity to financial divisions in society. In contrast to the BAME underrepresentation, the overrepresentation of the privately educated on Olympic teams was significant, the Summus report notes.

While the overall picture does not look dramatic – the United Kingdom population is comprised of 82.3% white people and 17.7% non-white, compared to a Rio 2016 overall GB team made up 85% of white athletes and 15% BAME athletes.

However, in the depths, the picture is much more dramatic, with swimming among the best funded but its Olympic squad entirely white. Among leading swim nations, that is not uncommon, swimming having long been a traditionally – but not exclusively – white realm.

Swimming, cycling and rowing are among the top four best-funded sports in the UK, with track and field. In terms of Olympic sports diversity, Rowing had one BAME athlete in Rio, swimming and cycling were “all-white” teams.

Ed Accura – ‘A film called Blacks Can’t Swim’ – not so much singing in the rain as scared in the rain as a result of having not learned to swim as a child… Photo Courtesy: Ed Accura

Those number reflect a long-term picture, tradition and reach, some of the barriers generated built by the BAME communities themselves, as Ed Accura’s “A Film Called Blacks Can’t Swim” points out so well.

If the picture is to change at elite level and sports are going to tap into talent in the BAME community, change needs to happen at all levels of sport to make each realm more accessible to all. In swimming, there is a huge added incentive required: swimming saves lives yet many children still never learn to swim.

A spokesperson for the BSA told Swimming World:

“When diversity and inclusion are not seen as motivating factors in the make up of our country’s most elite sport teams, national governing bodies are eliminating a huge demographic of our population that could be developed into talent to go on to become our county’s next Olympic medallists.

“At the very core of some of these most elite sports there are barriers that exist that preclude people from BAME backgrounds including factors around affordability, accessibility and of course representation and inclusion.

“We hope that UK Sport will immediately review its values and reconsider the power they have to make sports accessible and inclusive for everyone.”

To some extent, UK-Sport driven change is underway. Last September, Sport England and UK Sport announced a plan to action to tackle the diversity of sports boards with the help of recruitment group Perrett Laver. The need for action followed the publication of a “Diversity in Sport Governance” report (available here at the end of the news report of the day), which revealed that while women accounted for 40% of board members across Sport England and UK Sport funded bodies, diversity in areas such as ethnicity and disability “remained a challenge”.

In March, the former ASA, Swim England teamed up with the BSA “in a bid to further increase the numbers of the BME population participating in aquatic activity.”

At the times, Swim England said: “The partnership between the two organisations will aim to break down the barriers that prevent certain groups from taking part in swimming. Swim England and the BSA will work together to highlight the importance of swimming as a key life skill and educate the black community on water safety and drowning prevention.”

Former last year, the BSA represents all levels of swimming, from learners to Olympic hopefuls and including efforts to break down the barriers to swimming as a sport that is even considered as a realm for anyone who isn’t white.

Alice Dearing celebrating a podium finish at 2016 World Junior Championships on her way to the Britain senior team – Photo Courtesy: British Swimming

One of the founder members of the BSA, Alice Dearing is training for a place on Britain’s Open Water team at Tokyo 2020 in 2021. If she makes it, she would become the first black woman to swim for Britain at the Olympic Games. She is extremely rare: a Swim England survey recently revealed showed that “95 per cent of black adults and 80 per cent of black children in England do not swim”.

Last November, Swim England signed a partnership agreement with Sporting Equals to ensure the association’s Learn to Swim and Swim Safe programmes reach the BAME community.

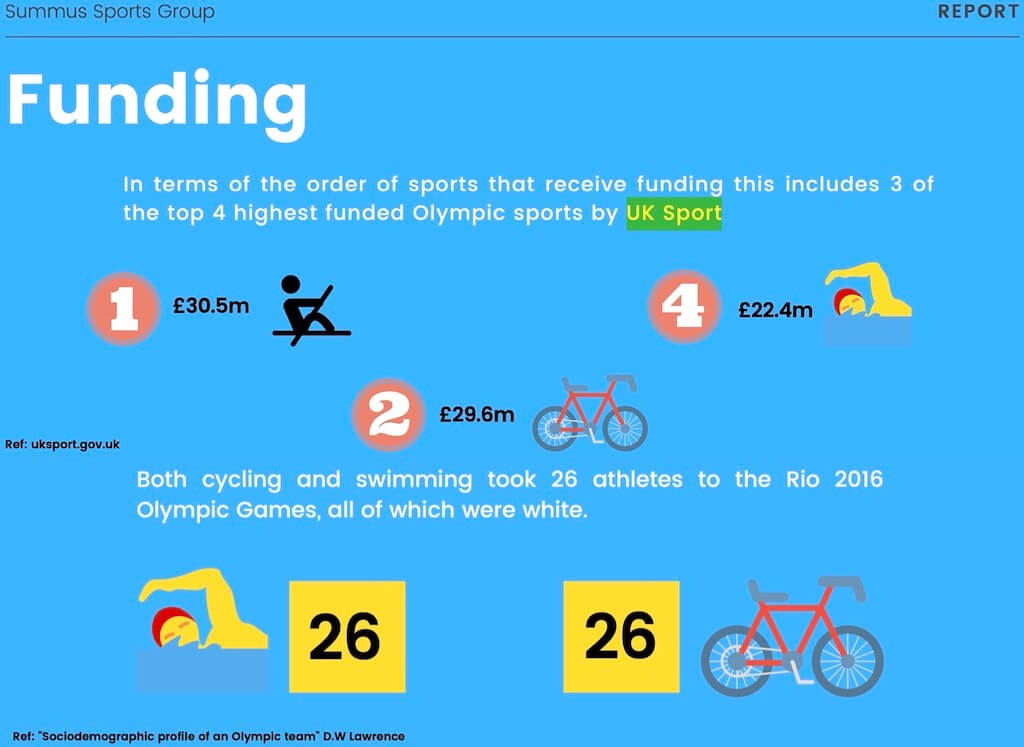

Swimming is matched by cycling among “all-white” Olympic squads, both with 26 athletes. Rowing had 1 non-white athlete. Those three sports are in the top four best-funded sports: rowing (£30m), cycling (£29.6m) and swimming (£22.4m) are the 1st, 2nd and 4th highest-funded Olympic sports.

At the Olympic Games in Rio, the reports notes, of the 23 Olympic sports representing Team GB, more than half showed significant bias towards white, privately educated athletes, according to research by a team at the University of Toronto in 2017, Summus noted.

The 10 most notable biases were found in equestrian, shooting, archery, field hockey, swimming, triathlon, rowing, road cycling, diving and sailing.

Of the 177 athletes those teams (plus related cycling teams such as BMX) sent to Rio, just two were “non-white”,one in hockey, the other in rowing.

Olympic sports diversity in the UK – Photo Courtesy: Summus Sports report ragout

The Summus Sports report comes in three parts:

Olympic Sports Diversity – overall ‘Movement’ report conclusion:

“The impact of race and education within the Olympic movement in the United Kingdom is a complex issue that varies across sports. The data shows that for the majority of sports and, as a result, for Team GB as a whole, white, privately educated individuals have a higher chance of both making an Olympic Games and winning a medal.

“Specific sports, such as Equestrian, shooting, triathlon, archery and rowing, demonstrated bias towards white and privately educated athletes. This bias is clearly a result of both the sports’ dependence on the private schooling system and its relative social status, due to the specialisation and cost of equipment and facilitates.

“Conversely athletics, boxing, taekwondo, and gymnastics demonstrated bias favouring non- white and non-privately educated athletes. This is no doubt in part down to the accessibility and affordability of the sports, but we must also be mindful of cultural influences on sports participation across race. Finance, as a barrier to participation and development in sport, on the other hand, should be scrutinised more fully. Cost and access to facilities are well- documented barriers to sport participation and advancement at every level.

“The conclusions are clear. With the exception of a small number of highly diverse and accessible sports, UK Sport funding of Olympic sports acts to reaffirming the socio-economic advantages and racial prejudices seen across the country, particularly in the education system. As a result, there is a strong bias towards white, privately educated athletes in a large number of sports that receive significant public money under the National Lottery investment scheme.

“Due to the short-term target of winning medals, funding is primarily spent on boosting Britain’s competitive advantage in sports that are particularly dependent on specialised and expensive equipment. Funding these sports and reaffirming the socio- economic advantages of the elite has come at the expense of diversity at an elite level and at the cost of funding for more widely played and accessible sports such as basketball.”

The suggestions as a result of this report are three-fold:

- Short term – diversity and inclusion to become a formal consideration for sports to

receive National Lottery funding. - Short term – invest in accelerator programs to increase the chances of success for

non-white, comprehensively educated athletes in sports that show significant biases

against them. - Long term – survey the accessibility of each sport that receives funding and mitigate

access-restrictions or evaluate the value of its continued inclusion in publicly funded programs.

Our commitment as an organisation in this space:

- We will use our influence within the industry and work with the athletes that we represent and their partners to facilitate accelerator programs in the areas where they are needed most.

- Continue to share information and to prioritise purpose, equality and diversity at the heart of every athlete strategy and partnership.