Too Much Heart To Swim

By Kristy Kinzer, Swimming World College Intern

Athletic careers can be shattered with one misstep, one break of focus, one freak accident that sidelines elite and rookie athletes alike. Every season, a team’s outcome can be defined by those whose potentials cannot be brought to fruition due to accidents and injuries.

But what if you had no control over your diagnosis or healing process? What if you were told you were a walking, talking cardiac arrest waiting to happen? What if, one doctor’s appointment later, you’re told you cannot compete again in the sport that has become a staple to your daily routine, identity, and social and competitive outlet? Some people’s spirits might crumple and become embittered. It is a rare person who can absorb this life-altering news and mold her life into one of outstanding strength, perseverance, and hope.

I’m fortunate enough to be able to put a name to this person- Hillary Glover. She’s a recent graduate from Calvin College’s accounting department (second to the left pictured below) with plans to become a CPA and work for Plante Moran in Chicago, Illinois. It is in her nature to already have a future plan and steady job lined up.

Photo Courtesy: Mrs. Glover

Matter of the Heart

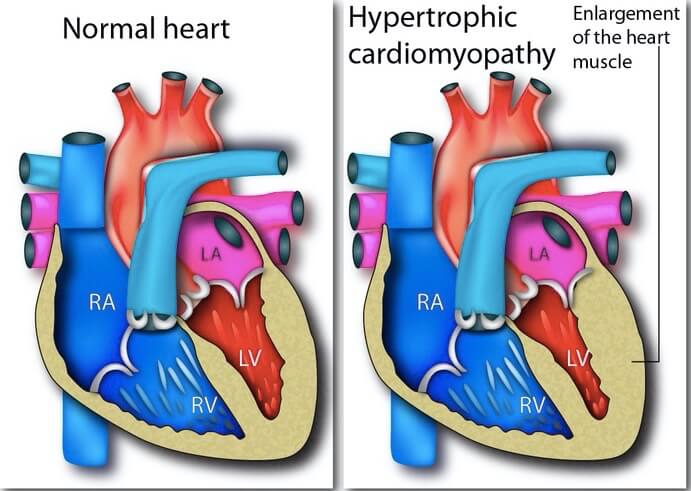

From the outside looking in, Hillary is not much different from any other athlete on campus. She’s strong, fit, determined, driven with schoolwork, and very sociable. She was voted captain of the Calvin swim and dive team and works hard toward her goals. No one would guess that the very heartbeat inside her chest could fail at any given time, especially if it crosses the threshold of 140 beats per minute. Many don’t notice the heart rate monitor she’s required to wear during every workout or the red box carried to every meet and practice in case she needed defibrillation. It has become a routine part of her life. But dealing with the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is anything but routine. It is terrifying, limiting, and chronic.

Photo Courtesy: Health Education Library for People

Diagnosis Day

HCM is a condition in which the muscle of the heart is excessively thick, particularly in the left ventricle, which pumps blood to the rest of the body. A thickened and stiffened heart wall prevents adequate amounts of blood from nourishing the body’s organs. It is the most common cause of sudden cardiac arrest in young people, particularly in athletes, and most do not realize they have the condition until it is too late.

Thanks to the diligence of a high-school nurse’s skills in detecting heart murmurs and follow-up with her primary care physician, Hillary was referred to the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital for more thorough testing just to be on the safe side. No one could have prepared her for their findings.

“On June 15, I was sitting in a room on the 10th floor of the Cardiovascular Center in Helen DeVos when I found out.” She vividly recalls the doctor’s words delivering the the news that his team of doctors were very surprised that nothing cardiac-related had yet happened to her, and that she had to be restricted from all competitive sports.

“I had sat quietly on the bed up until that point. But when those words came out of his mouth I felt like the world had frozen, and suddenly it all came crashing down on me in a billion little pieces. ‘No more swimming?’ I squeaked out, and then I couldn’t hold it in any longer. I broke down and sobbed,” Hillary described hearing her diagnosis for the first time. “Everything felt like it was in slow motion and all I could do was replay in my mind: ‘No more swimming. No more swimming. No more swimming.’”

Hillary had been captain of her swim team for the previous three years and was a part of the all-conference roster at her high school. “Basically, swimming was where I found my identity.” She began competing in the sport at the age of five and couldn’t imagine a life without it. When asked what helped her get through this time, Hillary credits her friends and family.

Photo Courtesy: Kristen Kinzer

“That senior swim season was far from easy watching from the sidelines. Seeing my spots on relays getting replaced and how much fun the girls were having in the pool made me hurt inside. Each day was a new challenge. But through this all I had the greatest support system imaginable.” Though being side-lined didn’t get easier, Glover says that she learned more how to accept her new reality as her future was out of her control.

Swimmer to Diver

Meanwhile, mail from recruiting schools continued to pour in, further aggravating the wound of her diagnosis. She dreaded telling each head coach the same story of having to quit swimming but would be interested in team management. But on her visit to Calvin College her senior year of high school, the head coach was unable to meet due to scheduling conflicts, so she met with the dive coach, Aaron Paskvan, instead. After hearing her story, the optimistic coach offered the option of diving. Naturally, Hillary was intrigued by the possibility of competing again.

With very limited experience in diving besides the occasional backyard pool party, Glover admits that her technique was less than optimal. “When I was a competitive swimmer, the only interaction I had with the divers was during my high school team, and at that point, I think we all wanted to be divers, especially during the days when practices were tough,” she jokes. From a swimmer’s perspective, it seemed as if divers mostly stood under warm showers or a heat lamp.

But with a bit of deliberation, the decision was final. Hillary was not going to let HCM take away her love for participating in a team sport, whether she had experience in it or not. After participating in a summer camp with Coach Paskvan to get a feel for the sport and his coaching, she signed liability waivers and became a college diver.

Adjusting to the New Norm

When asked about the most difficult aspect of transitioning sports, Glover comments: “The team dynamic is a big game changer when it comes to switching from swimming to diving. As a swimmer you’re a majority and a diver, minority.”

Photo Courtesy: Noah PreFontaine

In addition to the new social challenges, Glover faced heightened emotional challenges. “I simultaneously hated and loved my freshman year of diving. I tried not to compare myself to everyone else who has been doing it for years, but as hard as I tried not to, it just happens.” She laughs about how often she smacked on an attempted dive, but slowly adjusted to new goals and began focusing on the process rather than results. “Every day I’d go to practice and just try to remind myself to keep a positive attitude because I was fortunate to simply have the opportunity to continue athletics, and that’s really what I wanted.”

Glover also comments about the physical differences between swimming and diving. “In diving, working hard isn’t the same as trying harder. Diving is all about technique, grace, and not trying to speed things up to get the dive done. They’re totally different levels of difficult.”

Photo Courtesy: Heidi Glover

Heart Surgery

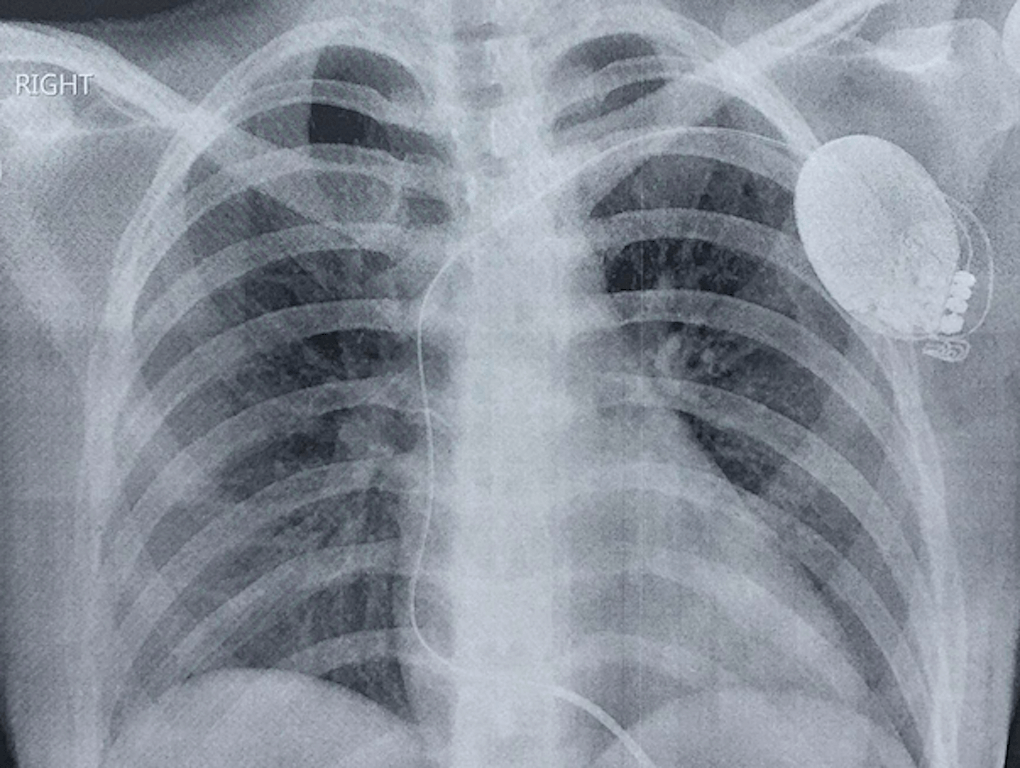

Glover competed with great improvements, almost qualifying for DIII NCAA Diving Championships her junior year. But three weeks before her college senior dive season, not only was she informed from her cardiac specialist that her heart condition drastically worsened, but also was told that open-heart surgery was no longer a matter of “if” but a matter of “when.” That August, she had an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) placed as a temporary solution until her scheduled open heart surgery during final exam week in December. A few days before this surgery, she met with the coaches to inform them that she would meet the team on winter training trip in Florida two weeks post-surgery, and she would be coming back to finish the season at the conference championships in February.

Photo Courtesy: Dirk Tanis

Our head coach was impressed by her drive but had his doubts about recovery time. But I knew if Hillary set her mind on a goal, she would find a way to accomplish it. After having 16 square centimeters shaved off her heart wall and enduring weeks of physical therapy, Hillary stepped up to the boards to dive for her team one last time, proudly sporting her surgical scars.

Photo Courtesy: Jeremy Crawford

Character in Adversity

Now that her college athletic career is behind her, Glover reflects on the bigger picture. “Having a heart condition has made me grow up. It’s made me face the possibility of death, which is not something every 21-year-old can say.” She also credits her heart condition with an attitude change. “I’m a pretty intense and tough person, so I don’t always feel bad for people when they’re struggling with things. But dealing with my own heart condition has helped me put difficulties into perspective and has allowed me to empathize with other perspectives too.”

Her courage has left a profound impact on those around her and continues to do so. “She is one of the strongest, most resilient people I know, and I’m blessed as a teammate and friend to have been able to witness Hillary’s journey,” Rachel Devries, high-school teammate and friend, said. Devries credits Glover’s positive mental attitude and encouragement as the only reason she joined and continued in the sport of swimming.

Glover encourages athletes recovering from injury or dealing with a debilitating diagnosis to keep an open conversation and dialogue with others to help with the rebuilding process. She also advises to continue an athletic pursuit. “Don’t give up. Athletes can’t just give up on being athletic. It’s a lifestyle and is so important for sanity, health, and everything else.”

For Glover, not giving up meant switching sports completely. “It’s just a matter of finding what you’re able to do and running with it,” she urges.

Too Much Heart

Well, there you have it. Quite literally and figuratively, Hillary Glover struggles with having too large of a heart. I’ve been a witness of her drive, love for teammates, and perseverance through setbacks, and she continues to amaze others with her can-do attitude. She hopes her story inspires others to fight through limitations and find a niche.

May we all follow Glover’s example and approach life with a little more heart.

Kalina Grace Emaus Anne Emaus

Angie Hascall Blackwell

Pam Stallings

Great piece, Kristy! Hillary’s story shows us that early detection of a heart condition is critical, and that having a heart condition doesn’t necessarily mean an athlete has to give up all sports activities. Very inspiring. We travel to schools throughout the US to test student athletes for heart conditions, so this story hit home.

Thanks, Cynda!

I’m so glad you check out athletes around the country–such a scary thing to deal with. I’m also a registered nurse, so medical issues hit home for me as well. Thanks for all you do!

Amy Tesar Colwell Todd Colwell; interesting read!

Thanks, Mike Murray. This sounds like Ryan’s situation to a “T”. I don’t think there is a day that goes by that he doesn’t miss swimming. I will have you know that the friendships that he built while swimming club are still alive. He still asks to get the “Dream Team” together.