Great Races: When Teammates Gary Hall Jr. and Anthony Ervin Shared Olympic Gold In 50 Freestyle

Tie Game: The 20th Anniversary of Gary Hall Jr. and Anthony Ervin Sharing Olympic Gold

Training together at the Phoenix Swim Club and living as roommates in the Olympic Village, veteran Gary Hall Jr. and upstart Anthony Ervin wrote an intriguing chapter in the history of sprinting when they shared the gold medal in the 50 freestyle at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney – 22 years ago on Sept. 22.

Because Gary Hall Jr. saw him every day, was fully aware of his talent level and knew he was capable of beating anyone in the world, the veteran Olympian and sprint champion had plenty of respect for what Anthony Ervin brought to the starting blocks.

Because Anthony Ervin saw him every day, was fully aware of his yearning desire and knew he wanted individual Olympic gold more than anything else the sport could provide, the upstart sprinter had plenty of respect for what Gary Hall Jr. brought to the water.

Together, Hall and Ervin wrote one of the most intriguing chapters in Olympic history, when they tied for the gold medal in the 50 freestyle – the one-lap dash which determines the fastest man in water – at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. The way they arrived at that point, however, was quite different and only added a level of depth to their tale.

Together, Hall and Ervin wrote one of the most intriguing chapters in Olympic history, when they tied for the gold medal in the 50 freestyle – the one-lap dash which determines the fastest man in water – at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. The way they arrived at that point, however, was quite different and only added a level of depth to their tale.

As the 2000 United States Olympic Trials in Indianapolis approached, Hall was the best-known name of those contending for a berth on the American squad. Deeply talented, he was a star at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where he anchored the United States to gold medals in the 400 freestyle relay and 400 medley relay, and won silver medals in the 50 freestyle and 100 freestyle behind Russian sprint legend Alexander Popov.

More, Hall hailed from a family with a rich swimming tradition. His grandfather, Charles Keating Jr., was an NCAA champion for the University of Cincinnati in the 1940s and his uncle, Charles Keating III, was a 1976 Olympian. It was Hall’s father, though, who had the greatest success in the pool until his son came along.

A three-time Olympian from 1968-76, Gary Hall Sr. won a medal at each of his three Olympiads, claiming silver in the 400 individual medley in Mexico City (1968), silver in the 200 butterfly in Munich (1972) and bronze in the 100 butterfly in Montreal (1976). His career was also defined by multiple national championships and world records in the 200 butterfly, 200 individual medley and 400 individual medley.

Hall Jr., although a sprinter, simply continued the family tradition. As he made his way up the ranks, Hall was one of the most outspoken voices in the sport. He was not afraid to raise concerns over performance-enhancing drug use and he possessed a deep confidence which was viewed by some as showboating, namely his shadow-boxing routine behind the blocks prior to races. More than anything, Hall was letting his personality shine.

In 1999, though, Hall’s serious side came to the forefront. Following an incident in which he collapsed, Hall was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes and doctors initially informed Hall that the diagnosis would put an end to his athletic career. Not satisfied with that outcome, Hall vowed to fight through his disease and managed to control his illness with proper attention and care.

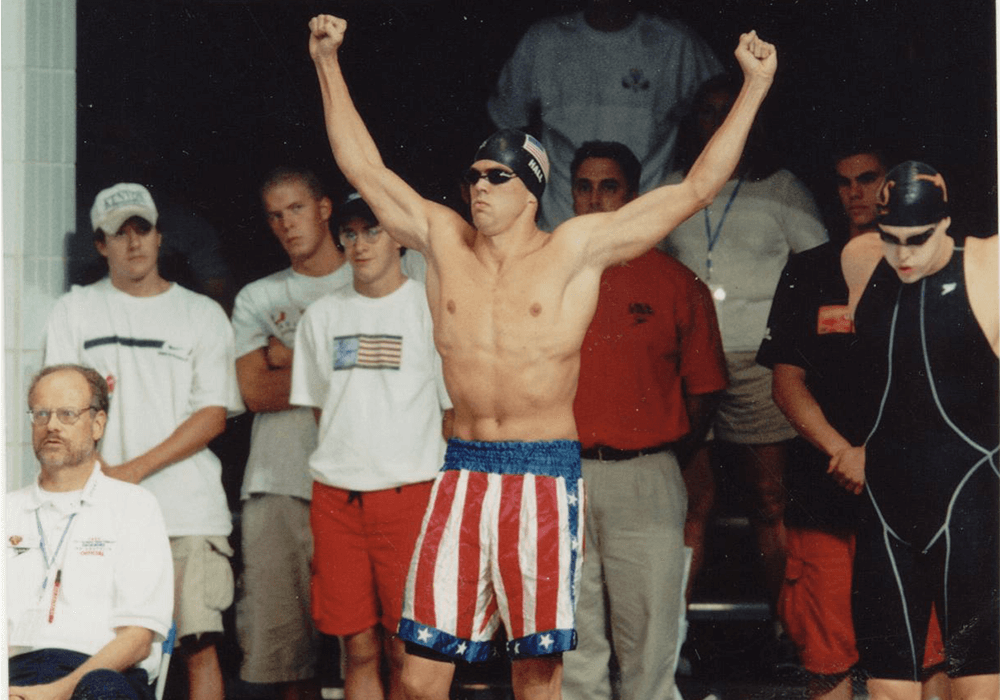

Gary Hall – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

As important, Hall became a visible figure in the fight against diabetes, regularly speaking about the positive and active lifestyle which can be enjoyed by those afflicted. He also took part in fundraising events and activities which gathered money toward research and diabetes care.

“The diabetes was really a major factor in my life, not just my swimming career,” said Hall, who was initially scared by the possible effects of diabetes, such as blindness or kidney failure. “The travel took something out of me. It affected my blood-sugar levels. But I paid attention to what I ate and made sure I got the right amount of insulin. It was so scary when I was diagnosed. I heard these horror stories and the statistics. My reaction was it’s just a matter of time. I’ve only got so much time before these things happen. But the quality of life a person with diabetes can have really comes down to the individual and the management that individual can provide. Other people have been able to successfully manage this disease and avoid very serious complications that stem from this disease, so it can be done. If there are complications, it’s difficult to blame anybody but yourself.”

While Hall was a well-established veteran, Ervin was a soaring youngster with the Sydney Games on the horizon. One of the nation’s top recruits coming out of high school, Ervin wasted little time making an impact upon his emergence at the University of California-Berkeley. During his freshman season, Ervin captured NCAA championships in the 50 freestyle and 100 freestyle, victories which quickly turned heads considering his precocious nature. Suddenly, Ervin was a legitimate contender to qualify for the United States squad bound for Sydney.

As much as Ervin’s talent captured the attention of the media, so did his upbringing. Born to an African-American father and Jewish mother, Ervin’s bi-racial background received headlines, primarily because the United States had never had an Olympic swimming medalist with black heritage. For his part, the introspective Ervin tried to shy away from that categorization.

“I have always been proud of my heritage,” he said. “But I don’t think of it in terms of first of this, first of that. It is like people are trying to pin it down to one definitive thing. I never thought about it. In the nature of American society today, I would think having diverse blood would not be a big deal.”

Their paths to Sydney different through the end of Ervin’s freshman year at Cal, Hall and Ervin came together in Phoenix, Arizona several months before the United States Olympic Trials. At the Phoenix Swim Club, sprint guru Mike Bottom – an assistant coach at Cal at the time – oversaw a talented collection of athletes, headlined by Hall, Ervin and Poland’s Bart Kizierowski, a world-class sprinter in his own right.

Training next to one another, Hall and Ervin now were following a similar blueprint. They took part in identical practices, constantly battled to get to the wall first and ate the same meals at the same restaurants. Aside from sharing Bottom as a coach, they also shared a sports psychologist and strength trainer.

The fact that Hall and Ervin trained together in pursuit of the same goal, and did so while maintaining and further growing a friendship, was not exactly the norm. While the Hall-Ervin combination worked in Phoenix, legendary coach Richard Quick was forced to alter his training approach in Northern California. With Jenny Thompson and Dara Torres both under Quick’s guidance, the Stanford coach had to separate the athletes because of rising tension and an ultra-competitive atmosphere which was not beneficial to anyone involved.

Clearly, Bottom had a knack for handling the situation with aplomb, while Hall and Ervin possessed the necessary maturity to thrive in such an atmosphere.

“Anthony’s talent was apparent from Day One,” Hall said. “I knew he was a real threat for the gold, and (I) predicted great accomplishments very early on, when he was unproven. I knew that it wasn’t going to be easy to beat him, increasingly cognizant of it as the season progressed. At the time, he did not comprehend or appreciate his talent, or the significance of the Olympic Games, which made him even more dangerous as a competitor. Still, I wanted to help him, and did. He helped me, too. Training with each other elevated both of us. Under the guidance of Mike Bottom (a brilliant psychologist), Anthony and I bought in to a philosophy that all of us had something to contribute and that all ships would rise with the sum contribution.”

The approach by Bottom was largely successful because of the way his athletes bought into his system. Although there was plenty of focus on sprint work in the pool, Bottom was an outside-the-box thinker who engaged his athletes in obstacle-course training and other approaches which broke up the monotony of lap after lap in the pool.

The varied coaching style of Bottom isn’t one which has caught on worldwide, but it has been highly successful. All one has to do is look at the success of his swimmers, most recently those he coaches as the head man at the University of Michigan. In 2013, Bottom led the Wolverines to the NCAA team title, the program’s first since 1995.

Photo Courtesy: Griffin Scott

“My goal was to change the way the world trains sprinters,” Bottom said. “I hate to characterize sprinters as a different animal, but they are a different animal. Most coaches end up trying to fit a square peg into a round hole, and we lose a lot of our sprinters.”

Leaving Phoenix for the venerable Indianapolis University Natatorium and the Olympic Trials, Hall and Ervin were confident in their chances to nail down berths to Sydney. Indeed, they flourished. Hall led all three rounds of qualifying while Ervin was third after the preliminaries, then moved into the second position in the semifinals and final.

In the championship final and with invitations to Sydney on the line, both Hall and Ervin broke the 10-year-old American record of Tom Jager, which had stood at 21.81. Hall touched the wall in 21.76 while Ervin wasn’t far behind in 21.80. The finish also enhanced the possibility of two Olympic medals in the event.

For good measure, Hall qualified individually for the 100 freestyle, thanks to a second-place finish, while Ervin’s fifth-place finish in the event landed him a berth on the American 400 freestyle relay. Still, the week in Indianapolis wasn’t void of a hiccup. After months of dueling in practice and chasing the same goals, Hall and Ervin engaged in a small spat.

“There was an uncomfortable flare-up at the Olympic Trials,” Hall said. “It was basically a brief snarling thing where we growled at each other. I forget what exactly it was over. I immediately wrote it off as the tensions of Trials. We both got over it immediately. Other than that one inconsequential exchange, I have always gotten on well with Anthony.”

Bound for Sydney, Hall and Ervin remained tight. At Hall’s request, he and Ervin were roommates in the Olympic Village, sharing a four-person suite with Chad Carvin and Ed Moses. The friendship they had forged in Phoenix only continued to grow, with both men getting a better feel for the other.

“Gary is very misunderstood,” Ervin said. “Until I roomed with him at the Olympics, I had never really gotten a true glimpse of what Gary is like. He’s very deep, and well spoken. We’re similar in a lot of ways.”

Before they dueled in the 50 freestyle, which is contested in the second half of the Olympic program, Hall and Ervin had the chance to join forces for the United States in the 400 freestyle relay. Despite teaming with Jason Lezak and Neil Walker to post a time under the previous world record, Hall and Ervin couldn’t lift the United States ahead of Australia, which used a world-record leadoff leg from Michael Klim to become the first country other than the United States to win the gold medal in the 400 freestyle relay at the Olympics.

It was a tough blow to take, especially considering the Americans’ legacy in the event, but the setback did not floor Hall or Ervin. Before the 50 freestyle, Hall rebounded to claim the bronze medal in the 100 freestyle. The 50 free, though, was the showcase event for Hall and Ervin, and it was an event stacked with talent.

Aside from the American entrants, Popov was the two-time defending world champion and set a world record just a few months prior to the Sydney Games. Meanwhile, the Netherlands’ Pieter van den Hoogenband was riding a hot streak, having already won Olympic gold and set world records in Sydney in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle. Kizierowski, too, was a factor, and a fellow beneficiary of Bottom’s training program.

“The coolest thing about Mike is he’s not afraid to be nontraditional as a coach,” Ervin said before the 2000 Games. “In some ways, I look at him more on a friendship level than the authoritarian coach. He does tell us what to do, but he gets on a personal level with each of us. If I don’t feel like doing something, he’ll say, ‘Let’s do something else. What do you want to work on?’ So you still get the work done, but your input matters and Mike works with you.”

Hall and Ervin moved through the preliminaries as the second- and fourth-fastest qualifiers, with Kizierowski leading the field. In the semifinal round, Hall topped Ervin in the first heat with van den Hoogenband prevailing in the second semifinal, ahead of Popov. It all set the stage for the final.

The middle of the pool was the focal point, with Hall in Lane Four, flanked by Ervin and van den Hoogenband. The mad dash over one length of the pool typically brings paper-thin finishes, but what the athletes saw when they touched the wall was a rarity. Hall and Ervin each stopped the clock in 21.98, followed by van den Hoogenband for the bronze in 22.03. Popov finished a surprising sixth, well back in 22.24.

The tie marked the second time in Olympic history in which the gold medal was shared, joining the 1984 final of the women’s 100 freestyle, which saw Americans Nancy Hogshead and Carrie Steinseifer post identical marks. For Hall and Ervin, digesting the result was not immediate.

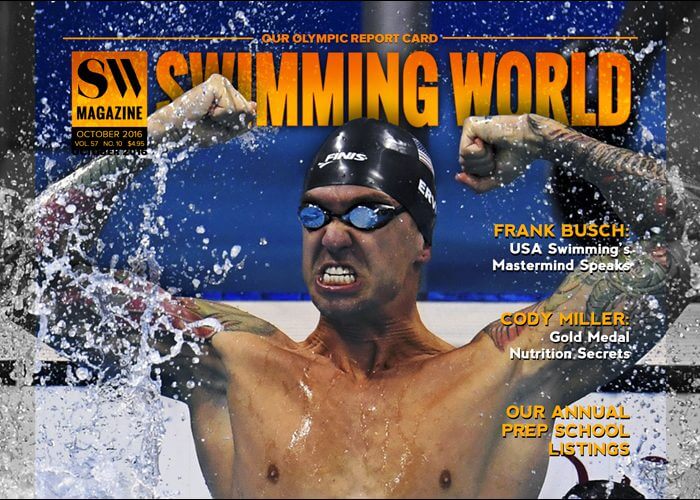

Anthony Ervin and Gary Hall Jr. shared gold in the 50 freestyle at the 2000 Olympics.

“Upon finishing the race, I immediately looked for the place next to my name,” Hall said. “I didn’t even look or care for the time. I saw the No. 1 next to my name and started celebrating. Then I noticed that my celebration was sedate compared to my teammate’s in the next lane. Happy for him, I looked back at the scoreboard to see a “1” next to his name. I thought “DQ” before I thought “tie.” A moment of panic. It felt like a very long time before it became absolutely clear to me what happened. A tie. Then, I couldn’t have been happier.”

Following Sydney, Hall and Ervin went divergent ways. Never one to focus on the World Championships, Hall dropped off the international scene until it was time to flip the switch for the 2004 Games in Athens, and a defense of his Olympic crown. Qualifying for the final with the fifth-fastest time, Hall delivered his finest performance while under pressure, repeating as Olympic champion in 21.93, .01 ahead of Croatia’s Duje Draganja, a training partner of Hall’s who was also mentored by Bottom.

Hall again disappeared after Athens, only to emerge in time for the United States Trials for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. This time, Hall couldn’t spin his magic and failed to qualify for his fourth Olympic team. He retired thereafter, as a 10-time Olympic medalist.

As for Ervin, his career seemed to be just taking off in Sydney and continued its upward trajectory at the 2001 World Championships in Fukuoka, Japan, where Ervin was the gold medalist in the 50 freestyle and 100 freestyle. Two years later, however, Ervin failed to advance out of the preliminaries of the 50 freestyle at the World Champs and he followed by walking away from the sport as a 22-year-old.

A free spirit, Ervin spent years uninvolved with swimming at a competitive level, although he gave lessons to help pay the rent. He bounced around the country frequently, played guitar in a band and even auctioned off his gold medal from the 2000 Olympics, with the proceeds going to victims of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

As his 30th birthday neared, he got back into training after an eight-year layoff. The results that followed were almost unfathomable. Ervin, long touted as a naturally gifted sprinter, proved to be faster than ever and qualified for the 2012 Olympic Games in London, where he finished fifth. A year later, he helped the United States to a silver medal at the World Championships in the 400 freestyle relay and placed sixth in the 50 freestyle, although he set a personal-best time in the semifinals.

Photo Courtesy:

However, what Ervin pulled off in 2012 and 2013 only served as a warmup for his biggest moment of all. After qualifying for the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Ervin wowed the world in South America when he upended reigning Olympic champion Florent Manaudou of France and captured the gold medal in the 50 free. In addition to becoming the oldest male Olympic champ in the sport’s history at 35 years old, his 16 years between Olympic crowns marked another record.

“I really felt like I had accomplished every goal I had set out to,” Ervin said of his sabbatical. “It became time to go back and reclaim some of the stuff I had sacrificed along the way. I was kind of shot down this tunnel. As a youth, as most people are, you’re not really given a ton of options for a variety of reasons. When something sticks, people often stay with it. For whatever reason, I couldn’t do that. I was convinced the grass would be greener somewhere else. Or, at the least, if I did make the journey that I would see the other side of that horizon, whatever was there. I think everybody’s got that to a certain degree. But I certainly had a lot of angst and resistance toward being pushed in the direction I had always been going. I really just needed freedom, so I took it.”

Undoubtedly, Hall and Ervin did things their way and boasted opposing tales. One was the veteran champion, the other the rising star. Hall possessed a passion for his sport and placed his focus almost entirely on one competition, the Olympic Games. Ervin, meanwhile, was content to leave the competition pool behind and explore other aspects of life.

But when their names are mentioned, one day immediately comes to mind, that moment on September 22, 2000 when Hall and Ervin, friends and training partners, stood together on the medals podium as Olympic champions.

“I don’t mind sharing the gold-medal podium,” Hall said. “It couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy, a guy I practice with all the time. It was like another a day of practice.”

Albeit with a lot more on the line.

One of my all time favorite races to watch! Wow!

Thank you for a very kind article. It brought back many great memories.

-Gary