The Paris Olympic Century: 100 Years Makes a Major Difference in U.S. Olympic Qualification

The Paris Olympic Century: 100 Years Makes a Major Difference in U.S. Olympic Qualification

America’s best swimmers will descend on Indianapolis next week for the U.S. Olympic Team Trials. By the end of June 23, the swimmers will know who will travel to Paris and, almost down to the minute, when and how often they will swim in the French capital at the end of July and beginning of August.

The group of Olympic swimmers that voyaged to Paris in 1924 had nothing close to that level of clarity.

Back in 1924, the path to get on the boat – not the plane, but the Steamship America – was far more opaque and far less standardized. With two qualification meets in the United States, one of which led to a cross-country trip with stops to reach the team departure point of New York – and a final qualification in Paris, the 1924 swim team presents an anomaly unthinkable now.

Officially, the 1924 Olympic swimming roster counts 40 individuals – 18 women and 22 men – who traveled to Paris (including divers and water polo players, of which there was substantial overlap, it’s 25 women and 39 men). But only 12 women and 14 men actually competed in swimming events in the Olympic Games.

The reason is a mazy qualification process that sought to appease various constituencies and the logistical challenges of the era long before today’s standardized system was designed.

East and West

The word “final” was thrown around a lot in 1924 when it came to which tryout for the Paris Games was most definitive. Most were illusory.

American hopefuls for the Paris Olympics enjoyed a multi-month buildup of meets. The best women in the nation were on display in early February, over a six-day meet in Miami that saw 17 world records fall. It included the New York contingent of swimmers from the Women’s Swimming Association – Agnes Geraghty set five world records to lead the way at the meet, after two American records at a meet in New York two weeks earlier. Chicago’s Sybil Bauer was also among the stars.

April brought the AAU championships, which included world records by Bauer, Bob Skelton and John Faricy. A week later, the U.S. Naval Academy held the early equivalent of the NCAA championships, then a men’s only affair.

The final – really, first final – Olympic qualification meets were held in early June, the men in Indianapolis, the women in Briarcliff Manor, New York.

The stars of the Women’s Swimming Association ahead of the 1924 Paris Olympic Games: Helen Wainwright, Aileen Riggin and Gertrude Ederle, New York Evening Post, Jan. 25, 1924

But even to get there, the field was winnowed by a pair of West Coast meets. Duke Kahanamoku and Wally O’Connor were among the leading swimmers and divers to descend upon Pasadena on May 20 at one. A week later, Warren Kealoha and Bill Kirschbaum set world records in Palo Alto at a “Far Western” tryout at Searsville Lake, the training location for Stanford University. A late May distance race in Coney Island helped set qualifiers for Trials.

The men’s chance to qualify for Paris came first, at Indianapolis’s Broad Ripple Pool from June 6-8. That was the first of seven times that Indy has hosted trials, with Broad Ripple staging women’s trials in 1952 before IU Natatorium hosted four Trials and now this year’s event at Lucas Oil Stadium.

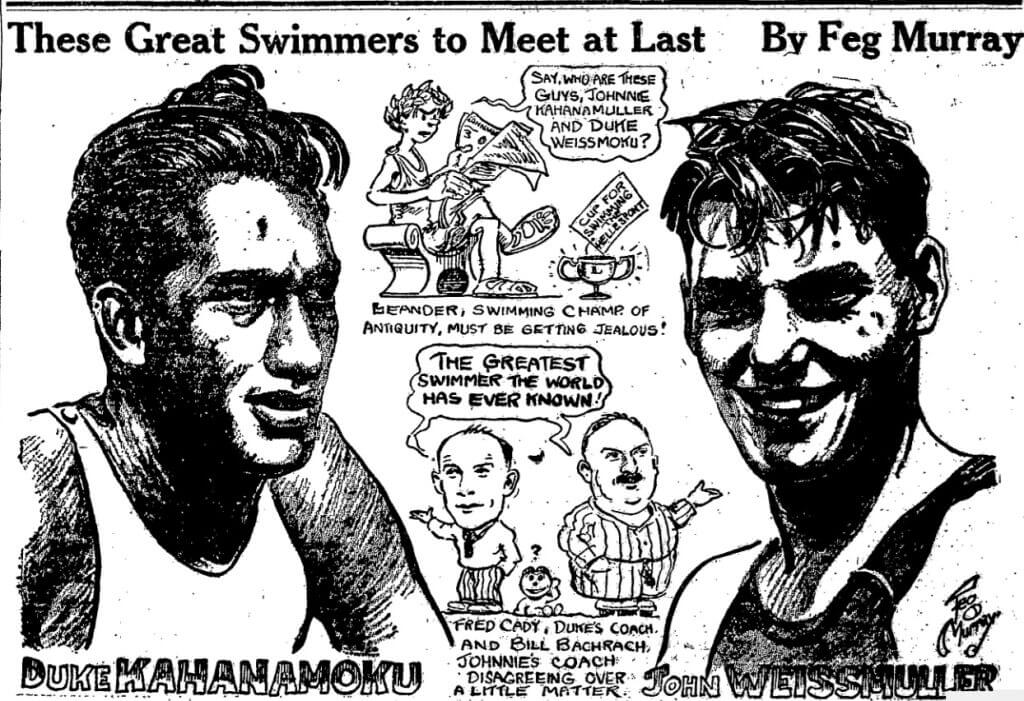

The marquee matchup in Indianapolis was the men’s 100 freestyle, regarded then as the premier race on the men’s program and attracting some of the nation’s top talents. Johnny Weissmuller, the star of Trials, bested Kahanamoku, who had won the gold medal at the Olympics in 1912 and 1920. Weissmuller’s time of 59.4 seconds was faster than Kahanamoku’s Olympic record from the Antwerp Games. Sam Kahanamoku was third.

“If there was any doubt in some minds that Johnny Weissmuller was king of the sprinters in the water, it was dispelled Thursday at Broad Ripple pool where the final Olympic swim trials are being held,” wrote the Indianapolis Times. “Weissmuller is clearly in a class by himself — one of those athletic marvels who stand out alone in his almost superhuman ability to flash through the water faster than any one ever has known to travel before.”

Weissmuller wasn’t done. He twice lowered Pua Kealoha’s world record in the 50 free, not yet an Olympic event, to 25.2 seconds, then bested Kealoha in the 200 free on the final day of the meet.

Dick Howell won the 1,500 free. Lester Smith captured the 400 free a day later, with Warren Kealoha leading an all-Hawaiian top three in the 100 backstroke. Skelton won the 200 breast in a time quicker than the Olympic record on the final day.

The women would convene June 7-8 in New York for their trials, what wire services called, “the greatest number of women swimmers ever gathered in a contest in the United States.” Territories represented included Hawaii, still three decades from statehood, and the Panama Canal Zone.

Women’s trials were a show for the WSA a stone’s throw from home. Geraghty won the 200 breast, and Gertrude Ederle won the 400 free over teammates Helen Wainwright and Martha Norelius (whose name the New York Times never could quite get right) on the first day. Bauer was the star of Day 2, lowering her 100 back world record by nearly four seconds. Hawaiian Mariechen Wehselau, in her first trip to the mainland, won the 100 free.

All those qualifications were preliminary, as it was known before embarking to Paris that some swimmers “would try out abroad” for spots on the team. It created a chance for Olympian who never got to compete.

When in Paris

Doris O’Mara Murphy had a New Yorker’s upbringing. Born in Yonkers, she swam at the WSA in a 20-yard pool in the basement of a Manhattan building, when on to coach at Huner College, graduate from the College of New Rochelle and play six-man basketball.

Officially, O’Mara is an Olympian. Her experience looks much different than you might expect, though.

At Olympic Trials in June, O’Mara finished second to Bauer in the 100 back. Third was Frances Schroth of San Francisco.

That earned the 15-year-old to a trip to Paris. But in the pool, it guaranteed nothing. As she explains, in a 1987 oral history with the LA84 Foundation:

“I qualified for the 100-meter backstroke, practiced for it, and expected to swim in the event. But then, without advance notice, this girl with her family had come over to Paris and they gave her a chance to try out against me. She touched me out by a thin margin in the backstroke, and that was disappointing.

“But then I look back on it . . . and she didn’t have any of the fun and experience going over with the whole team on the ship as I did. Also, as I recall, she didn’t do any better than I would have done in her time. I was 15 at the time and it just didn’t seem fair.”

That swimmer, by all indications, is Florence Chambers, who finished fourth in Paris. Bauer won the race in an Olympic record time of 1:23.2, four seconds up on Phyllis Harding of Great Britain. Aileen Riggin won bronze. Chambers was fourth in the five-swimmer final. O’Mara never got to compete in Paris.

O’Mara’s story of a missed Olympic moment is all too common for the ’24 contingent.

It began during trials, with news from chairman the swimming’s Olympic Selection Committee John T. Taylor that “owing to a shortage of funds, the America team would be reduced from thirty-six to twenty-four men.” (There were only five individual male events, at three entries per, plus one relay, and four individual and a relay on the women’s side.) Expense cutting would be a theme throughout the Games, as the Americans descended on a continent still barely a half-decade removed from the society-shaking Great War. Chambers was in position to take O’Mara’s spot principally through her family’s outlay of funds.

Riggin, who won fancy diving at Trials after having won the first ever gold medal in Olympic diving in Antwerp in 1920, didn’t swim the 100 back at Olympic Trials, citing a time trial in Paris. The same was reported by the New York Times in June for Ederle and Wainwright to “try out abroad, having made the team in the 400-meter swim on Saturday” for spots in the 100 free.

Relay spots were up for grabs in Paris trials, which was perhaps more in line with our modern expectations. Weissmuller’s spot was set in the 800 free relay, but Ralph Breyer, Harry Glancy and O’Connor beat out Howell and Sam Kahanamoku for spots on July 9. The last spot on the women’s relay went to Euphrasia Donnelly, over Wainwright and Norelius.

Some changes in Paris were more pedestrian. Faricy, for instance, broke his ankle upon arrival in France, reportedly while stepping off a train. The entire U.S. delegation – 275 men and 24 women – traveled together across the Atlantic in part due to cost. That left swimmers training in a tank on deck during the Atlantic passage, hardly conducive to performance. In France, they endured long, bumpy bus rides from the women’s quarters in Rocquencourt to the pool that did them no favors.

Ederle in particularly was affected. “More heavily built than the others, she became so muscle-bound that even regular massage failed to relieve her,” coach Louis Handley, her WSA mentor and the head coach of the women’s team, wrote in the USOC’s official Report on VIII Olympiad Paris. “In the 400 meter race she fell short ten seconds of her record, showing how far she had gone back.”

The final final team

On the men’s side, most of the qualifiers from Indianapolis would end up swimming at the Paris Olympic Games. Weissmuller won gold in the 100 free ahead of Duke and Sam Kahanamoku, the same order of finish as Trials. Weissmuller added gold in the 400 free, an event where he was the only American to make the final. (Smith swam it in Paris. Breyer did not start.)

Howell qualified for the semifinals in the 1,500 but did not start. The top American finisher, Adam Smith of Erie YMCA in Pennsylvania, was not among the top four finishers at Trials but was selected by the committee at the conclusion of the meet. (Howell and O’Connor finished first and second in Indy, followed by Clyde Goldwater and John Hawkins.) Kealoha turned his win at Trials into gold in the 100 back, where Trials runner-up Henry Luning was disqualified. Silver in Paris went to Paul Wyatt, who beat out Charles Pung in a trial in France for the third spot. All four backstrokers were officially selected at the end of the Indy meet.

Among the women, Geraghty won silver in the 200 breast between a pair of British swimmers. Eleanor Coleman, who finished second at Trials, and Matilda Scheurich, third at Trials and celebrating her 14th birthday less than a week before her Olympic swim, didn’t make the final.

The same three qualifiers in the 400 free filled the podium in reverse order of their trials finish, Norelius winning gold ahead of Wainwright and Ederle. Ederle, but not Wainwright, won a spot in the 100 free via a Paris trial at the expense of Donnelly. That turned into bronze for Ederle behind Lackie and Wehselau, both Trials qualifiers. Donnelly led that trio in winning the 400 free relay.

It wasn’t a lost cause for those who didn’t swim in Paris. The team traveled through Europe, with stops in Belgium and England. In London, they competed against a British Empire team that included Boy Charlton. Several Olympians who didn’t swim in Paris – among them O’Mara, Margaret Ravior and Frances Schroth – swam there. Some of the 1924 team ended up representing the U.S. in a meet with the Japanese empire.

Despite not swimming, O’Mara called her time in Paris “an outstanding experience.” She would go on to be part of the 1928 team as an assistant manager via her WSA connections. That led her into coaching, where she founded the Connecticut Women’s Swim League and helped mentor 1956 Olympic medalist Joan Rosazza. She died in 1997 at 88 years of age.