The 1980 U.S. Olympic Trials Represented a Road to Nowhere

The 1980 U.S. Olympic Trials Represented a Road to Nowhere

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the final day of the 1980 United States Olympic Trials. The competition was held after the conclusion of the swimming events at the Moscow Games, an unusual circumstance for athletes who were robbed of the opportunity to compete on their sport’s biggest stage.

Every Olympic Trials, emotions on both ends of the spectrum are familiar. For some, jubilation is expressed, the long-term goal of becoming an Olympian officially realized. For others, disappointment is expressed, the long-term goal of becoming an Olympian doused – sometimes by hundredths of a second.

When the 1980 United States Olympic Trials were held in Irvine from July 29-Aug. 2, the typical range of emotions was missing. Instead, a dour mood permeated the five days of action, and no one could blame the contending athletes for that sense. After all, this version of the Olympic Trials would not lead to the Olympic Games. Politics saw to that.

Months earlier, President Jimmy Carter announced the United States would boycott the 1980 Games in Moscow in response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979. Still, USA Swimming made the decision to hold its Olympic Trials and officially name members of the U.S. Olympic Team. Never mind that the swimming competition at the Olympics had already concluded.

“The people organizing the meet and U.S. Swimming have been really great planning all this, but I’ll be happy when the week comes to an end,” said Rowdy Gaines of the 1980 Trials. “I’m not blaming anyone, because nobody could have done better under the circumstances. If this was solely the Olympic Trials, it would be a different story.”

Most of the swimmers who would have contended for Moscow berths in a normal year were present in Irvine. However, there were varying degrees of preparedness – both physical and mental. While some athletes were ready to produce top times, others were not in peak form. Still more found themselves in a middle ground. So, when USA Swimming developed what it felt was a fine idea for each event, the notion didn’t fit the target of all.

Before each race, the scoreboard not only showed the event’s finalists, but also flashed the medal-winning times from the Moscow Games. That move was designed to give the athletes something to chase, and to allow the United States to prove it would have shined brightly had Carter not squashed the dreams of hundreds of athletes across a variety of sports. Yet, that decision for the scoreboard did not take into account the nature of racing and how racing at the actual Olympics would have generated greater intensity and desire.

“I could guarantee you that if this were the real Olympics, 90% of the swimmers here would go faster,” said Mike Bruner, the 1976 Olympic champion in the 200 butterfly. “Our officials did everything they could possibly do to build up this meet, but this isn’t an Olympics. I know. I’ve been there.”

Bruner’s words represented the feelings of many of his fellow competitors, but the fact is, officials needed to drum up some suspense. One way to achieve that goal was to generate a virtual meet: The United States vs. the 1980 Olympic podium. Indeed, numerous events revealed the American power that was absent from Moscow. Consider some of the best performances:

-

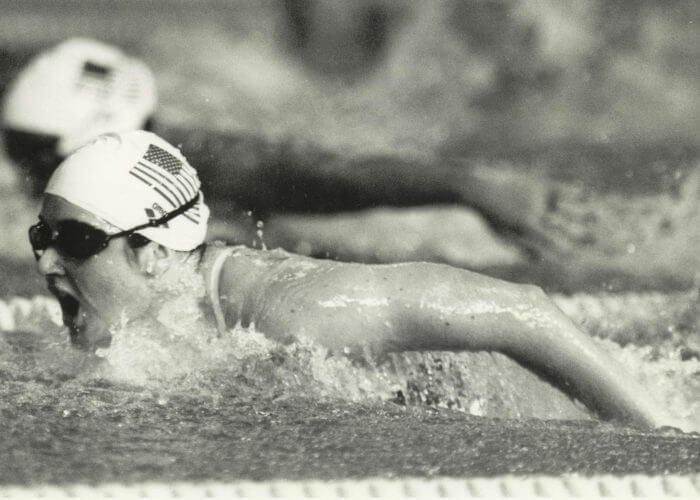

Mary T. Meagher Photo Courtesy: Tony Duffy

In the 200 butterfly, Mary T. Meagher and Craig Beardsley set world records that would have easily captured gold medals in Moscow. Meagher’s time would have prevailed by four seconds while Beardsley would have won by well over a second.

- In the women’s distance freestyles, Kym Linehan posted efforts in the 400 freestyle and 800 freestyle that were quicker than the winning marks in Moscow. The same could be said for Gaines in the 100 freestyle, with his 200 free performance just off the gold-medal time in the Soviet Union.

- Tracy Caulkins and Sippy Woodhead would have given the East Germans all they could have handled in several events while Jesse Vassallo was quicker in Irvine than what it took to win the 400 individual medley in Moscow. As for Bruner, he could have won medals in multiple events.

- Steve Lundquist and Bill Barrett were each quicker than the Olympic-winning time in the 100 breaststroke while William Paulus and Matt Gribble bettered the Moscow gold time in the 100 butterfly.

There were others, too, who would have been factors, and for those who did not swim times that bettered those produced at the Olympics, it is important to remember this caveat: It’s much more difficult to race the clock than it is to race a rival standing on the adjacent block. Then again, some saw time comparison as the only option.

“I’ll always feel disappointment about it,” Meagher said at the end of the 1980 Trials. “When they played the Olympic song here, I had tears in my eyes. But there was nothing I could do except look up at that scoreboard and compare my time.”

Linehan is often overlooked during discussion of the 1980 Olympic Team. She would have gone head-to-head with East Germany’s Ines Diers and Petra Schneider in the 400 freestyle and she would have dueled with Australia’s Michelle Ford in the 800 freestyle. Instead, she had to wait four years for Los Angeles, where she placed fourth in the 400 freestyle.

Although her best days were behind her by the time she raced at the 1984 Games on home soil, Linehan has maintained a measured outlook on her situation.

“1980 was a difficult time and things just didn’t work out,” she once said. “There were many wonderful guys and girls who didn’t get their chance to go. You just have to deal with it and move on. After 1980, and even though I was considered one of the old ladies, I felt fortune enough to have the opportunity to make the team in 1984. I was just very fortunate to be able to achieve it. I have numerous friends for whom 1980 was their year and they, unfortunately, didn’t make the 1984 team, so to those athletes, it’s heartbreaking.”