Thanks to Dressel, Joseph Schooling Has His Hustle Back

Editorial content for the 2018 NCAA DI Championship coverage is sponsored by TritonWear. Visit TritonWear.com for more information on our sponsor. For full Swimming World coverage, check event coverage page.

Morning Splash by David Rieder.

Joseph Schooling was disgusted. In his signature event, the one in which he won Olympic gold one year earlier—the first-ever for Singapore in swimming—he was routed.

On top of the world after dethroning Michael Phelps in the 100 fly in 2016, here was Schooling finishing tied for third in a World Championship final, with a former teammate finishing almost a full second ahead.

Caeleb Dressel won the World title in the 100 fly in Budapest, his time of 49.86 the second-fastest clocking in history, for his third individual gold medal of the meet. Schooling tied with Great Britain’s James Guy for bronze in 50.83.

“That was phenomenal,” Schooling said of Dressel’s performance. “There are no words to describe how fast that is.”

But when he assessed his own performance, Schooling did not mince words.

“I got my a** kicked,” Schooling said. “There’s no other way to say that. By my standards, that’s pretty unacceptable.”

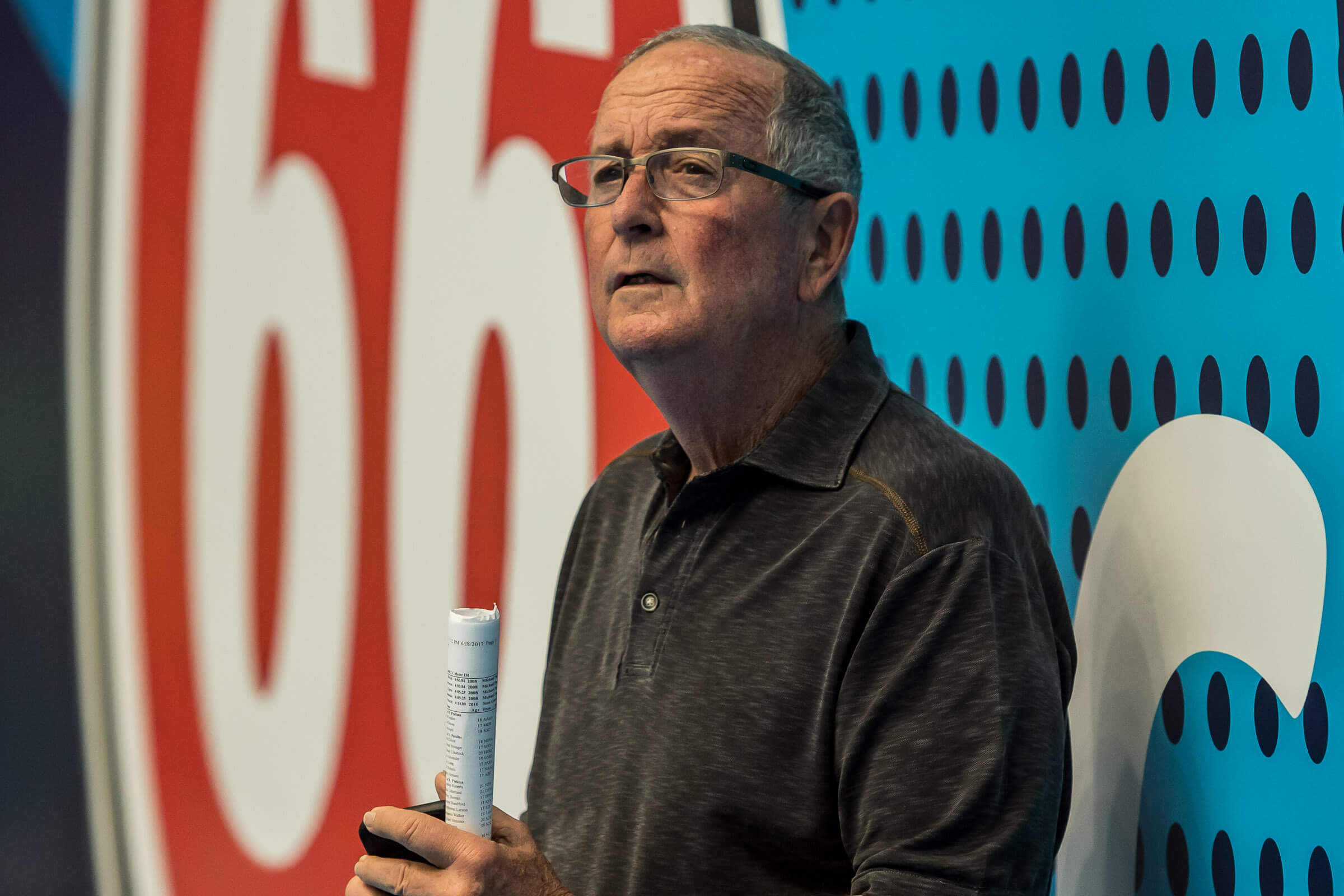

What happened? Schooling had been forthright even before Worlds—after the Olympics, his focus had wavered. Eddie Reese, Schooling’s coach at the University of Texas, explained that his pupil had “accomplished his lifetime goals” all in one race. In Singapore, he had become something of a national hero. “It was hard to get him back,” Reese said.

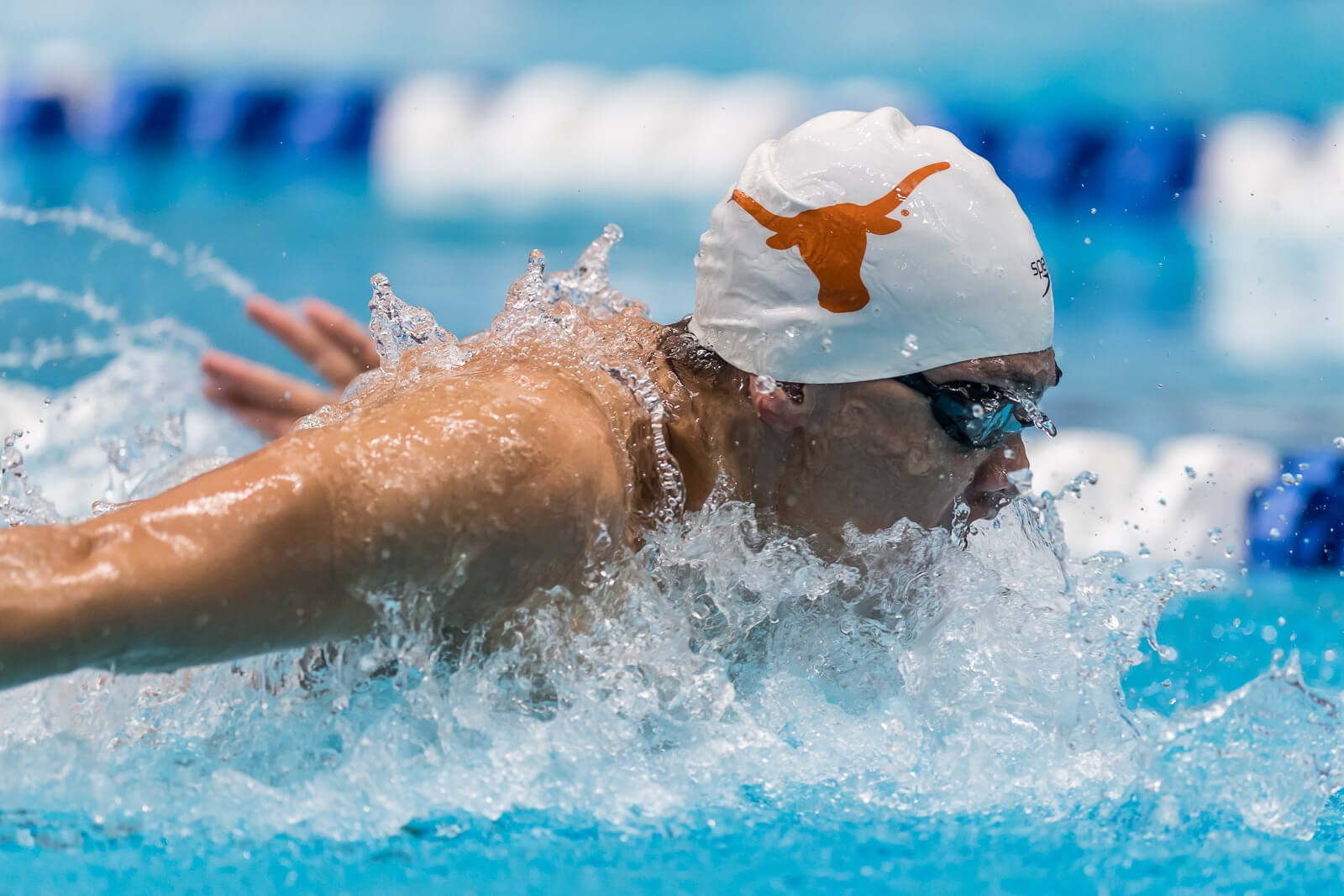

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

After a rough effort at the NCAA championships in March, when Schooling lost to Dressel in the 100-yard fly and missed out on scoring entirely in the 200 fly, he explained that he just had not trained enough, but he figured that he had enough time to turn it around before the World Championships.

And sure, Schooling’s performance in Budapest was fine but not nearly good enough. But the 22-year-old had no regrets—he let off some steam in the post-Olympic year and got to experience life as a typical college student.

“I did things that I previously didn’t have the chance to do, which was awesome,” he said. “Pros and cons, obviously. Cons are you’re not going to get the results that you want. If you don’t put the work in, put in less than half the work that you’re used to, you’re going to get less than half the results.”

Less than half his usual training? Schooling nodded. No exaggeration.

===

Immediately after his defeat at Worlds and then again in January, Schooling made this very clear: He’s not upset about his results from the World Championships. Not because bronze is acceptable to him—it was not—but because it re-invigorated him.

“It was my more fuel to the fire, and my motivation right now is Caeleb. He’s the main reason I get out of bed in the morning, and that’s awesome,” he said. “That’s what keeps me going whenever I don’t feel like putting up with this anymore. It’s awesome—you need something like that.”

After Budapest, Schooling took stock of his swimming. He knew that his preparation over the past year had been sketchy, at best, and if he had any expectations of restoring his forward trajectory, he needed to make sure that he was not squandering his opportunities.

“If I’m doing something, I need to do something to the best of my ability,” he said. “You make huge changes if you want things bad enough.”

At the World Championships, Schooling recalled how Reese had warned him about the perils of his lackadaisical training routine after the Olympics. But this year, he’s been paying extra attention to the often corny but invariably astute words of his legendary coach.

Texas men’s coach Eddie Reese — Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

The first mantra that Schooling recalled was: “The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.” In other words, prioritize.

So when he came back to Austin, Texas, for his senior season as a Longhorn, Schooling considered his priorities: “School and swimming fast.” Getting his homework done and getting to bed early became priorities. Schooling committed to stick to his nutrition plan that he had followed before the Olympics, eliminating fast food, soda and what he called “late-night college activities.”

Also from Reese, there was this: “Take care of yourself, take care of each other, and the rest will take care of itself.”

“Basically, that means don’t be selfish,” Schooling said. “That might not make a lot of sense swimming-wise, but if the team is doing well, you’re going to be doing well. You doing well is a byproduct of the team.”

Even for Schooling, who has an Olympic gold medal and national hero status in his home country, the message of acting like an adult and being accountable to his team struck a nerve.

===

In swimming circles and even in wider sports circles, Schooling will likely never shake the title of “man who beat Michael Phelps in his last individual race.” The photo of Phelps with a 13-year-old Schooling in 2008 has made the rounds since Rio and likely will again before the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.

But in person, Schooling is rather unassuming. He has a down-to-earth personality, and he’s only six feet tall, much shorter than most elite-level swimmers. He’s not afraid to show emotion or be upfront about how he’s feeling, but he’s also not particularly loud.

Photo Courtesy: Erich Schlegel-USA TODAY Sports

He’s a 22-year-old college senior, and like most college seniors, he finds it bizarre thinking back on all that had happened in three years, thinking back to a time before he won two NCAA titles his freshman year at Texas in 2015, before he was a well-known name in the swimming world.

Schooling rattled off the names of Kip Darmody, Grant Rogers, Nick Munoz and Jake Ritter—none of them swimming superstars, but “they were my seniors. I remember almost idolizing them and looking up to them like a big brother. For me to be in that position right now, when I think about it, is kind of weird.”

He thought back even further, to when he first came to the United States and to the Bolles School in Jacksonville, Fla. That was in 2009, when Schooling was in eighth grade.

“I still remember moving into the dorms and how it felt,” he said. “When you go to a new place, things smell different, and you kind of remember that and you relate the new places to that scent. I can still remember how the dorms smelled.

“It’s been many, many years, and it’s gone by really fast.”

The next three years should pass just as quickly. Schooling will likely have his first shot to get some revenge on Dressel next month, when the two meet in the 100-yard fly at the NCAA championships.

“I’m going to make the most of it this year, and hopefully I can go four-for-four—we can go four-for-four,” Schooling said, correcting himself mid-sentence. “We’ll see what happens.”

Schooling was a freshman on the first of three straight Texas national championship teams, and he is the only swimmer returning who has been a key contributor on all three of the previous teams.

After March, with his college swimming career behind him, Schooling will have his sights set on the Asian Games in September in Jakarta, Indonesia, leaving a long course rematch with Dressel to wait until 2019. And then, of course, he will defend his Olympic gold medal one year later in Tokyo.

Successfully pulling off a second consecutive Olympic gold in the event would put Schooling into an exclusive category that right now includes only Phelps. The 100 fly comparisons aside, Schooling has joined Phelps in transcending swimming and becoming something of a legend—but only when he’s in Singapore.

Right now, he spends the majority of his time in the United States, specifically under the eye of Eddie Reese in Austin, Texas. That way, he’s not a celebrity but just Joseph Schooling, a senior on the University of Texas men’s swim team who has accomplished his dreams but is still striving for more.

.jpg)

Cool

Great article David

Does he have a realistic shot though?

Good question. I see Caleb swimming 49.5 before Tokyo. Can Joe get down that low?

Defending Individual Olympic Champion. ? World Record Holder Title Next?

No mention at all of all that braggadocio by Schooling back in May about swimming a WR in the 100m fly in Budapest. I guess Schooling thought that if he said it on record, then he would have no choice but to put in the effort. Now we know he had a choice.