Sydney Anniversary: A Look Back at Australia’s Epic Olympic Relay Triumph of 2000 and an Air Guitar Concert (Video)

A Look Back at Australia’s Epic Olympic Relay Triumph of 2000 and an Air Guitar Concert

Twenty-four years ago, the Olympic Games were in full force in Sydney, and one of the early highlights of the action was a triumph by Australia in the 400-meter freestyle relay. It was an event that featured several intriguing storylines.

*****************************************

More than 17,000 passionate Australian fans stood and yelled, anticipating a moment their country had long envisioned. The Sydney Aquatic Center was the focal point of the 2000 Olympic Games, and as the first night of competition on Sept. 16 neared its end, those who filled the stands in this swimming-crazed country sensed it was time for something special to unfold. In a little more than three minutes, the atmosphere would be either pure jubilation or complete sorrow. Here, we look back to what has become known as the Air-Guitar Race.

Hope is a powerful sentiment. In the months leading into the 27th Olympiad, Australia was deemed a major threat to the United States’ stranglehold on the 400 meter freestyle relay title. With two bona fide stars, veteran Michael Klim and teenage sensation Ian Thorpe, the Aussies featured stellar bookend options for the relay, with the middle legs of Chris Fydler and Ashley Callus more than reliable. With the necessary ingredients present, Australia was confident it could capture—on home soil—the biggest Olympic victory in its history.

The 400 freestyle relay became part of the Olympic schedule at the 1964 Games in Tokyo, and in seven editions of the event (the relay was not contested in 1976 and 1980), only the United States had mined the gold medal. Actually, Team USA dominated the event, winning by an average margin of more than two seconds. Adding to the lore of the United States was the fact that it also was a perfect 8-for-8 at the World Championships.

Conversely, Australia didn’t have much of a tradition in the event, having won just a silver medal (1984) and two bronze medals (1964/1968) in Olympic action. A positive for Australia, however, was its silver medal behind the United States at the 1998 World Championships. It was a loss by just 28-hundredths and came without the presence of Thorpe, who was certainly going to have an impact on the outcome in Sydney. More, the Aussies edged the United States at the 1999 Pan Pacific Championships, and while that competition didn’t feature a worldwide field and the U.S. was without some big names, it was still a confidence boost.

However, Australia’s optimism hardly dented the American belief that an eighth consecutive Olympic title was on the horizon. Despite the knowledge that this Olympiad would likely produce its biggest challenge, the United States boasted a daunting lineup of Anthony Ervin, an upcoming sprint star, Neil Walker, Jason Lezak and Gary Hall Jr.

The son of a three-time Olympian by the same, Hall was equally known for his ability in the water and an oversized personality. Hall was never afraid to express his opinions on a variety of topics—from doping to the opposition—and brought to the blocks a showmanship that was unusual for a generally conservative sport. One of Hall’s calling cards was wearing Apollo Creed-esque shorts, seen in the Rocky movies, and performing a shadow-boxing routine behind the starting blocks.

After emerging from the gauntlet that is the United States Olympic Trials as the champion of the 50 freestyle and runner-up in the 100, Hall was slated to contest four events in Sydney—two individual and two relays. His first event would be the 400 free relay, and Hall felt the United States would establish early momentum.

“I like Australia, in truth. I like Australians,” Hall said in an Olympic diary he kept for Sports Illustrated. “The country is beautiful, and the people are admirable. Good humor and genuine kindness seem a predominant characteristic. My biased opinion says that we will smash them like guitars. Historically, the U.S. has always risen to the occasion. But the logic in that remote area of my brain says it won’t be so easy for the United States to dominate the waters this time. Whatever the results, the world will witness great swimming.”

As the teams made their way to the deck, the Aussie crowd was already in a frenzy. Earlier in the night, Thorpe fulfilled the massive potential that had been placed upon his shoulders when he won the gold medal in the 400 meter freestyle, setting a world record of 3:40.59. The 17-year-old was nothing short of spectacular, beating Italian silver medalist Massimiliano Rosolino by nearly three seconds and American bronze medalist Klete Keller by more than six seconds. Racing in his own realm, Thorpe provided his home nation with much to celebrate, and delivered on his vast promise.

Ian Thorpe – Photo Courtesy: Adidas

At the 1998 World Championships in Perth, a 15-year-old Thorpe became the youngest male world champion in history when he won the 400 freestyle. Simultaneously, he ignited conversation about becoming an Olympic champion and establishing himself as one of his sport’s all-time greats. This speculation did not just come from journalists seeking an angle ahead of the Sydney Olympics, but also from high-ranking individuals within the sport.

When asked about the potential of young athletes, most coaches will choose their words carefully, cognizant of not creating undue pressure. Don Talbot, Australia’s head coach during the emergence of Thorpe, did not abide by that thought process. Rather, Talbot took a contrasting approach, speaking openly and audaciously about Thorpe’s skill set.

“I’ve never seen a better swimmer than him,” Talbot said. “He’s got a great feel for the water. He makes it look easy. His maturity, that’s what you notice. He’s 17, but he seems like he’s someone in his 30s or 40s. It’s almost spooky. It’s genetics gone bloody crazy. He could be the swimmer of the century.”

Thorpe handled the pressure placed upon him with aplomb. Through his victory in the 400 freestyle, he proved he wasn’t overwhelmed by having his image adorn the front of buildings and billboards, from having his name in countless headlines and from having an entire sporting venue chant, “Thorpey, Thorpey, Thorpey.”

While Thorpe’s win in the 400 freestyle elated the Aussies in attendance—and the millions watching on television—the 400 freestyle relay carried greater significance. It was a chance for Australia to supplant the United States, and it meant that Thorpe, although supported by three teammates, was carrying a nation’s hopes in his well-documented size-17 feet.

“As soon as I walked out there, it was like a gladiator walking into the Colosseum, hearing the sheer noise of the crowd,” Thorpe said. “I was ready to race.”

Aside from the United States facing its biggest test in Olympic waters in the event, Hall’s comments added to the race’s intrigue. The Team USA veteran may have been complimentary of Australia as a country and recognized that a battle awaited, but he also predicted an American victory, taking a page out of the book of Joe Namath, the National Football League quarterback who famously predicted a New York Jets upset over the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III.

If Hall thought his comments were innocuous and were going to fly under the radar, he quickly learned otherwise. Newspapers throughout Australia picked up on the American’s words and, in an instant, they were splashed across numerous front pages and websites. At the same time, Hall became a villain, the “smash-them-like-guitars” portion of his statement seemingly the only part that received focus.

“We came down to the lobby, and there it was on the front page of the paper,” Klim said of Hall’s infamous words. “To be totally honest, we really didn’t take it too seriously, and despite what people think, it wasn’t really motivating for us. We knew we were walking into something that was going to be incredibly tough. The Americans had never been beaten at the Olympics and were world record holders.”

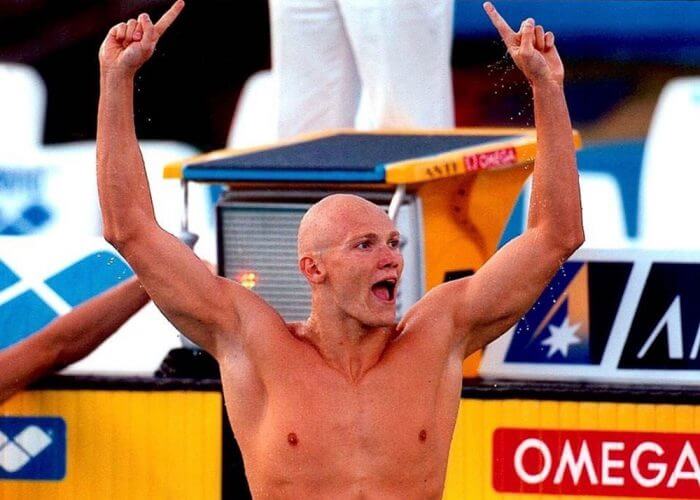

Gary Hall

Following the pre-race introductions, it took a few extra seconds for the crowd to settle down and allow the meet referee to start the race. As much as the Aussies in the crowd were excited for the possibility of home-turf success, there was an equal level of tension and nerves. What if Australia did not take advantage of this opportunity? How long would it take for another chance to arise? This one took nearly 40 years and the span of eight Olympiads, and the prospect of not coming through was sickening.

With the partisan crowd eventually quieted, the eight leadoff swimmers took to their blocks, but this race was about the United States in Lane 4 and Australia in Lane 5. For the Aussies, the event could not have started any better.

Slicing through the water in powerful fashion, Klim propelled Australia into an early lead and continued to build an advantage over Ervin. While the American teenager produced an opening split of 48.89 to put the United States in second place, Klim covered his two laps in 48.18, which cut 3-hundredths off Alexander Popov’s previous world record in the 100 free of 48.21, which had stood for six years. Not surprising, the already amped-up venue was now roaring in overdrive.

“I wasn’t going for a personal best or anything,” Klim said. “I just wanted to get the guys a pretty good lead. I knew if I did that, the guys would do their jobs.”

Staked to a lead of nearly a full second (71-hundredths), Fydler entered the water second for the Aussies, with Walker handling the leg for Team USA. At the turn, the Australian lead had been all but erased by Walker, but Fydler was known as the better finisher and made up most of the ground he yielded in the final 15 meters. With Walker splitting 48.31 to the 48.48 of Fydler, the United States trailed at the race’s midway point by 54-hundredths.

Into the water third were Callus and Lezak, who engaged in a duel that resembled what was produced by Fydler and Walker. Lezak immediately pulled even with Callus and even gave the Americans their first lead at the 250-meter mark. But Callus was the stronger racer in the closing strokes and put the Aussies back in front as he touched the wall for the exchange to Thorpe. Off of Lezak’s split of 48.42, compared to the 48.71 of Callus, the Australians were now in front by only 25-hundredths.

For Lezak, Sydney launched a decade-plus-long stretch as a relay leader for the United States. On 13 occasions, Lezak won a medal for the United States in global action in either the 400 freestyle relay or 400 medley relay, with eight of those medals gold. His crowning moment arrived in 2008 when Lezak etched himself in Olympic lore by pulling off an epic comeback in the 400 free relay. With the United States trailing France by a sizable margin on the final leg, Lezak continually reeled in Frenchman Alain Bernard and touched just ahead of him at the finish, the comeback win keeping alive Michael Phelps’ march to eight gold medals.

Michale Klim

The matchup of Thorpe and Hall on the anchor legs was a contrast of styles—in the water and on land. While Hall was a pure sprinter and went on to share the gold medal in the 50 freestyle with Ervin later in the week, Thorpe was best known as a middle-distance star. Hall’s showman persona was countered by Thorpe’s measured and quiet demeanor. What they shared was a desire to represent their countries and to perform in the spotlight.

The next 100 meters produced an epic showdown between Thorpe and Hall, and put the bow on one of the greatest races in Olympic history. As expected, Hall pulled even, then ahead of Thorpe, as the future Hall of Famers raced their first laps. At the turn, Hall held a half-body-length lead, but could he maintain that edge over his rival, who was unquestionably the better finisher?

With 15 meters left and Hall tiring, Thorpe pulled alongside his foe and then ahead. As they hit the touchpads, the scoreboard flashed a world-record time of 3:13.67 for the Australians—19-hundredths ahead of the United States’ 3:13.86, also under the previous world record of 3:15.11, set by the USA in 1995. Hall actually outsplit Thorpe, 48.23 to 48.30, but it was not enough, and magnified the importance of Klim’s spectacular leadoff leg.

Upon finishing the race, Thorpe thrust a fist in the air and wasted little time hopping out of the pool to celebrate with his teammates. Hugs, fist pumps and waves to the crowd accounted for some of the celebratory actions from the Aussies, but the best was to come.

Much to the satisfaction of the fans, the Aussies took part in an impromptu air-guitar performance, an obvious reaction to Hall’s earlier comments. Although Klim initially tried to play off Hall’s comments when the Aussie claimed they did not serve as a motivating force, the deckside antics said otherwise.

“I think it was (Fydler) who suggested it,” Klim said. “We whispered in each other’s ears, ‘Let’s do the air guitars.’ That wasn’t planned nor had we spoken about it. Hadn’t been mentioned at all, but on the spur of the moment we did it.”

Klim added, “But I must say, Gary Hall was the first swimmer to come over and congratulate us. Even though he dished it out, he was a true sportsman.”

Hall was nothing short of gracious as he analyzed the race, and his performance was superb. Not only did Hall generate a split that was slightly quicker than what Thorpe managed, it was the third-fastest in the entire race, bettered only by Klim’s leadoff and the 48.12 delivered by Lars Frolander on Sweden’s sixth-place squad.

The rest of the week was sensational for Hall, who complemented his joint gold in the 50 freestyle with Ervin with a gold medal as a member of the American 400 medley relay and a bronze medal in the 100 freestyle. Four years later, Hall repeated as Olympic champion in the 50 free.

“I’d be a liar if I said it wasn’t somewhat disappointing,” Hall said of the relay loss. “In the same breath, I’d say we were close to a second under the world record. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. Tonight was something the swimming world has never seen before. The last 50 meters were rather painful. I went after it. This is the Olympics, all or nothing. I doff my swimming cap to the great Ian Thorpe. He had a better finish than I had.”

The setback to Australia in the 400 freestyle relay not only snapped the United States’ 15-race winning streak in the event in global competition, but it also started a drought for Team USA. In 2001, Australia won gold in the 400 free relay at the World Champs, with Russia winning the event at the 2003 World Champs, a year before South Africa won Olympic gold in Athens.

For all Thorpe accomplished during his illustrious career, which wrapped after the 2004 Olympics in Athens, Sydney will always hold a special place in his memory.

“It would have to be the best day of my life, the best hour, the best minute,” Thorpe said. “To be able to dream and to fulfill it is the best thing an individual can do. It’s amazing to be in this situation and to perform well. I’m one of the select few athletes who have performed at their best at the Olympic Games. The statistics on that are very slim. It’s one of the things I wanted to do. It was pretty amazing in front of my own crowd, and it was just fortunate I was able to perform well in front of them. It really was a dream come true. When you race in Australia, you can’t let them down. I’m on such a high.”

So was an entire nation.

Congratulations

If you look at the vision, Thorpe exits the pool before the last swimmer has finished and was lucky not to be disqualified

Yes, noticed that too. He should have been DQed.

Chris Fydler

It was so wonderful to see Hubris get its comeuppance!

David defeating a supremely confident and arrogant Goliath!

So Sweet!