Women’s History Month: Aussie Fanny Durack a Pioneer in Olympic Women’s Swimming As The First Champion

Women’s History Month: Aussie Fanny Durack a Pioneer in Olympic Women’s Swimming As The First Champion

Today, March 1, marks the beginning of Women’s History Month. To mark the beginning of the month, we look at the arrival of women in the Olympic pool, where Australian Fanny Durack became the first Olympic swimming champion among women, over 100m freestyle, on July 12, 1912.

Takeoff to Tokyo (Fanny Durack) – From the April Issue of Swimming World Magazine

When the Olympic Games return to Tokyo this summer, one of the highlights will be a swimming schedule that is identical for men and women, the 1500 freestyle added for the ladies and the 800 freestyle added to the program for the gentlemen. But the first four editions of swimming at the Modern Olympics did not feature equality, women not involved until 1912, at which point Fanny Durack made a major splash.

Not long after Hungarian Alfred Hajos became the first Olympic swimming champion, winning the gold medal in the 100 freestyle at the 1896 Games in Athens, Australia’s Sarah “Fanny” Durack developed the urge to learn to swim. It wasn’t that Durack, a youngster at the time, was inspired by Hajos’ efforts, or the performances by any other male swimmer.

Rather, Durack’s desire to swim was triggered out of necessity and in the pursuit of peace of mind. While on vacation as a 9-year-old, Durack struggled with the surf in her native land, and it was that experience which convinced her to become water safe. It was a decision which made Durack swimming’s first female superstar.

From 1896, when the first Modern Games were held in the birthplace of the Ancient Olympics, through 1908, only men were allowed to compete in swimming at the Olympics. During that time, the likes of Hajos, American Charles Daniels, Great Britain’s Henry Taylor and Hungary’s Zoltan Halmay emerged as the sport’s standouts.

It wasn’t like women were banned from the Olympics altogether during that stretch of time, as female athletes competed in events such as sailing, tennis and equestrian as early as the 1900 Games in Paris. Swimming, though, didn’t create a coed program until the 1912 Games, which were held in Stockholm, Sweden.

When it was announced women would be invited to compete in Stockholm, some countries jumped at the opportunity while others were disinterested. Only 27 women took part in the two swimming events, the 100 freestyle and 400 freestyle relay, with host Sweden and Great Britain sending six athletes each. Australia sent two swimmers, Durack and Mina Wylie, while the United States opted to send no women, despite fielding a team of seven men.

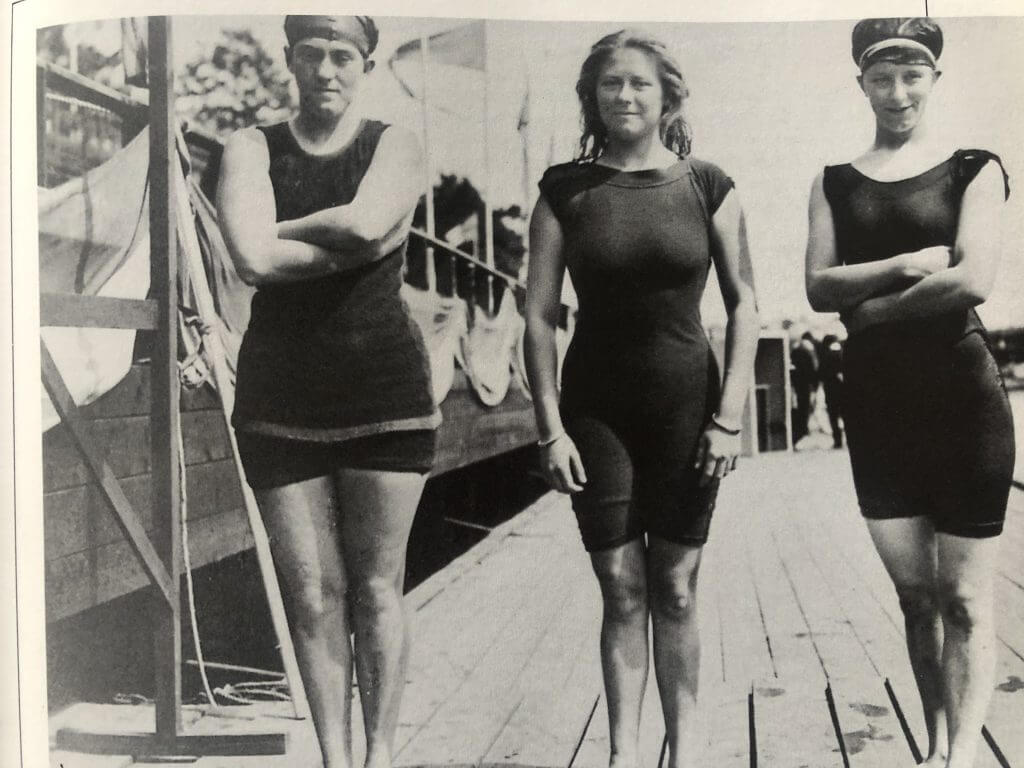

BelleMoore, Jennie Fletcher, a team chaperone, Annie Speirs and Irene Steer at Stockholm 1912 – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

While Durack had put together an impressive career, Wylie actually held the upper hand over her countrywoman in the leadup to the 1912 Games. Wylie beat Durack on several occasions at the Australian Championships and was considered a gold-medal favorite as much as Durack, who had the higher profile.

Getting to the Olympics, however, proved to be an issue for Durack and Wylie, with politics playing a role. Considering the role politics have played throughout the history of the Olympic Games, maybe it was fitting Durack and Wylie had to play a waiting game.

“The Aussie men in charge of selecting the team for the 1912 Games declared that it was a waste of time and money to send women to Sweden,” wrote Craig Lord in an article for the former SwimVortex website.

“The rule book didn’t help, either. The New South Wales Ladies’ Amateur Swimming Association regulations held that no women could compete at events where men were present. A public outcry resulted in a vote and rule change at the association and Durack and Wylie were allowed to make the journey to Europe – provided they paid for themselves. The wife of Hugh McIntosh, a sporting and theatrical entrepreneur and newspaper proprietor, launched a successful appeal for funds and with money donated by the public, family and friends, Durack sailed for Sweden via London, where she was reported to have trained half a mile a day.”

The competition pool was hardly high-tech in nature, constructed in Stockholm Harbor and consisting of salt water. But Durack wasn’t derailed by the conditions. Representing Australasia, a combined team from Australia and New Zealand, Durack opened her Olympic career in grand fashion, setting a world record of 1:19.8 during qualifying heats of the 100 freestyle. She followed by winning her semifinal easily, and then captured the gold medal with a time of 1:22.2, more than three seconds quicker than Wylie.

Great Britain’s Daisy Curwen was expected to be a medal contender in the final, but the former world-record holder was forced to withdraw from the competition after the semifinal round due to a bout of appendicitis. It was Curwen’s world record which Durack broke during the qualifying heats.

With Durack and Wylie the only Aussies competing in swimming, Australasia could not field a squad for the 400 freestyle relay, although it tried. Durack and Wylie offered to swim two legs each if Australasia was given the chance to race, but officials denied the request and Great Britain’s quartet of Belle Moore, Jennie Fletcher, Annie Speirs and Irene Steer went on to win the gold medal by nearly 12 seconds over Germany. Fletcher was the bronze medalist behind Durack and Wylie in the 100 freestyle and spoke of the limited practice time she and her teammates had in preparation for the 1912 Games. Said Fletcher years later:

“We swam only after working hours, and they were 12 hours and six days a week. We were told bathing suits were shocking and indecent, and even when entering competition, we were covered with a floor-length cloak until we entered the water.”

With only two women’s events, as opposed to the seven on the men’s program, there is no telling what Durack could have done if given the chance to contest additional events. But a lack of equality in the Olympic schedule has been more commonplace than not during the 100-plus years of the Games. From the first time women competed in swimming at the Olympics through the 1972 Games in Munich, men’s events always outnumbered women’s events.

And while men and women each competed in 13 events at the 1976 and 1980 Games, there were fewer women’s events over the next three Olympiads. Since 1996, however, the number of events between the genders has matched, albeit with a caveat. Through the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, there was inequality in the length of the longest events on each program. While men’s distance swimmers contested the 1500 freestyle as their gender’s longest event, women covered just more than half that distance via the 800 freestyle.

A change is coming next summer, thanks to the International Olympic Committee’s decision to expand the men’s and women’s programs. The addition of the 1500 freestyle for women is belated recognition of the gender’s ability to handle demanding tests of skill and endurance.

A parallel can be found in the history of track and field. It wasn’t until the 1984 Games in Los Angeles in which women contested the marathon, and in some years prior, women’s distances were capped at 1,500 meters while male athletes were given the opportunity to double in the 5,000 and 10,000.

Katie Ledecky – Photo courtesy: TYR

“I was happy to see it,” said world-record holder Katie Ledecky of the addition of the 1500 freestyle. “I think adding the 1,500 was a long time coming. It’s good that there’s parity in the men’s and women’s distance events now.”

From 1912-1918, Durack set 11 world records over various distances, including three in the 100-meter freestyle. Her fastest time of 1:16.2 from 1915 lasted as the world record for five years, until American Ethelda Bleibtrey won Olympic gold in 1:14.4. A Durack-Bleibtrey duel would have been a highlight event of the 1920 Games, but illness prevented Durack from racing.

After being denied the chance to defend her Olympic title in 1916 due to the cancellation of the Games by World War I, Durack was hoping to repeat in 1920, but appendicitis put an end to that dream. More, Durack came down with typhoid fever and pneumonia a week before Australia’s athletes were scheduled to sail to Europe for the Antwerp Games.

In between competitions, Durack took part in numerous world tours, along with Wylie, in which they would race one another and demonstrate the Australian crawl, the stroke which Durack made famous and used to become a world-record holder. Durack’s vast achievements earned her induction into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1967, the third year of the Hall’s existence.

“Fanny Durack not only took on all comers the world over, but beat all comers the world over for eight years in the formative years of women’s swimming,” reads Durack’s profile in the International Swimming Hall of Fame.