Swimming’s Place in Sports Activism

By Colin Hogan, Swimming World College Intern

Perhaps it’s fitting that 2016 has seen a renaissance of social activism in sports.

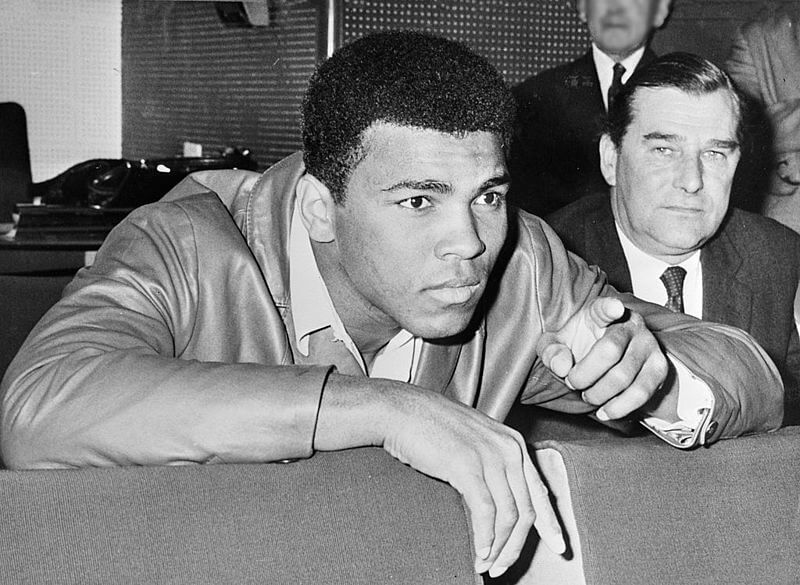

On June third of this year Muhammad Ali passed away after a decades long struggle with Parkinson’s syndrome. He was a fighter in every sense of the word, a champion for the oppressed as well as in his profession. He was The Greatest, and not just according to his own bravado; in 1999 the BBC named him the Sports Personality of the Century; in 2005 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush.

Among Ali’s iconic moments was lighting the torch for the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games.

We see the moment as a triumph of the human spirit and as quintessentially Olympic; the shaky Ali overcomes the symptoms of Parkinson’s to symbolically open the Games, allowing for the pureness of sport and competition to continue while also allowing us to reflect on his personal strength and successes.

There are so many stories from his many battles that come to mind when re-watching that moment, but many of his hardships aren’t told as often. We remember and shadow along to “The Rumble in the Jungle” and the “Thrilla in Manila,” but how often do we romanticize Ali’s abstention from the Vietnam War? From age 25 to 29 Ali was prohibited from boxing in all 50 states because he refused the draft, citing his Muslim faith.

And just a few days after the Atlanta Opening Ceremony Ali received a medal as replacement for the gold he won in 1960, but which he had long since departed with, having thrown it into the Ohio River out of frustration at his country after being denied service at a whites-only restaurant.

The image of Muhammad Ali lighting the Olympic torch is enduring and, after engaging with the fullness of his story, it should symbolize equally the richness of his struggles and the resonance of his triumphs.

In July of this year, barely a month after Ali’s passing, the heir to the title of biggest name in American sports, LeBron James, took a stage at the ESPYS in Los Angeles with fellow NBA stars. Before that crowd and a national viewing audience, James invoked his predecessor while calling athletes to lives of activism:

“Tonight we’re honoring Muhammad Ali, the GOAT. But to do his legacy any justice, let’s use this moment as a call to action to all professional athletes to educate ourselves, explore these issues, speak up, use our influence and renounce all violence and, most importantly, go back to our communities, invest our time, our resources, help rebuild them, help strengthen them, help change them. We all have to do better.”

There is almost no other way to describe the moment but as a passing of the torch. As one great flame is reduced to its last ember, another comes after to reignite it, renewing the causes of social justice within the arena of professional and elite sports. Whether or not a great cauldron of social change is lit, like the one that presided over the Atlanta Olympic Stadium, remains to be seen.

Issues of social justice for LeBron and his companions on that stage are less theoretical quagmires than they are real, tangible experiences where solutions are needed. LeBron has spoke of fearing for his children while Dwyane Wade has lost family members to gun violence—if their individual stories aren’t enough then check out this or this.

And certainly there has been progress even from the time of Ali, who won his gold medal before the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, to the time of LeBron and D-Wade, who as teammates won two Olympic medals, the most recent of which came the same year (2008) that the first African-American U.S. President was elected.

Though we should celebrate these achievements, we cannot use examples of progress to halt its march forward. As LeBron put it, “We all have to do better.”

In the sport of swimming, initiatives of progress and inclusion ought to be less contentious than they have been in the NBA and NFL, where backlash against athletes has dominated the discourse.

That’s because swimming is as much a practical and life-saving skill as it is a sport and pastime, and historical realities have made it so that the construction and regulation of swimming pools has worked to exclude minority communities in the United States. Jeff Wiltse is the author of the book Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pool in America, and after protests in McKinney, Texas in 2015 he gave a brief look into that social history for an article in the Washington Post.

The USA Swimming Foundation has conducted research to understand the dangers that swimming poses, especially to minority communities. The USA Swimming Foundation, in partnership with the University of Memphis, “found that nearly 70% of African American children and nearly 60% of Hispanic children have low or no swim ability, compared to 40% of Caucasians,” in a 2010 nationwide study.

Additionally, the study found that “if a parent does not know how to swim, there is only a 13 percent chance that a child in that household will learn to swim.” So not only do African American and Latino children suffer today from higher rates of swim inability, but they are very likely stuck in a cycle where their future progeny will also not learn to swim and drown at higher rates. (According to the CDC African-American children drown at a rate nearly three times higher than their Caucasian peers.)

National numbers on swim ability seem to affect the composition of the membership of USA Swimming, the national governing body for competitive swimming. According to Mariejo Truex, USA Swimming’s Director of Programs & Services, “as of last year [2015-2016]… African-American membership is at 1.1% and… Hispanic/Latino membership is at 3.2%.” She noted that “faster growing populations are… Asian communities [whose total membership stands at] 6.2% and Mixed [ethnicity persons, whose total membership stands] at 4.0%.” USA Swimming members self-report this data by checking a box.

The good news is that governing institutions like USA Swimming are doing the appropriate research and implementing programs to reach many previously excluded communities. For example, USA Swimming’s Facilities Department, headed by Mick Nelson, offers programs to build new pools and help maximize pool space and community benefit. The NCAA, which is the governing body for many collegiate sports including swimming, sponsors an office of inclusion that works to compile an ‘NCAA Race and Gender Database’ and also focuses on issues of hiring and retention in collegiate sports.

There’s plenty of work to do still, surely, but aiding the efforts of institutional change is the success of athletes who serve as role models. In an email, Truex commented on the importance of representation:

“What we’re hoping to see is a greater number of athletes of color enter the sport and reach the highest levels. Having role models to follow can help guide these younger swimmers as they navigate our sport. Young athletes will often seek out role models that they can empathize with. They often choose those that are similar to them in culture, race or appearance. Having elite athletes from underrepresented communities helps connect our youth to this dream since it provides them a path to follow.”

My little swimmer says, "I Got Next!" @simone_manuel #SimoneManuel #Swimming #History #TeamUsA pic.twitter.com/xjeRABQ1fZ

— Nett (@Laylas_Mommy_13) August 12, 2016

And while the inclusion of ethnic minorities in swimming seems especially difficult work due to their historical underrepresentation in swimming communities, USA Swimming is also working to make sure that the struggles of the LGBTQ community is given appropriate attention, study and requisite support. Recently, USA Swimming published a LGBTQ Cultural Inclusion Guide, and Truex has said, “the overwhelming response has been very positive.”

Swimmers may never have the impact on social awareness like an Ali, Wade or James, simply by competing in a sport with a smaller fan base, but their work can directly contribute to saving lives from drowning and inject diversity into a population that currently has very little. If they were to choose to use their platform, Truex says that USA Swimming will be in full support: “It is each person’s right to decide what to do with their influence and platform. It is our job as an organization to support our athletes in any way we can.”

All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine nor its staff.

An important topic discussed by a handsome author.

Great article Colin!! Thank you for sharing your insight and bringing light to this.