Swimming’s Symphony: The Journey of Blind Swim Coach and Paralympian, Tharon Drake

By Taylor Covington, Swimming World College Intern.

Tharon Drake placed his feet as he always had, letting his hand slide over the leathery curve of the basketball in search of its familiar spot. Sinking into the usual stance, he shot – this time anticipating the resounding thump of the ball off the backboard. On cue, Drake leapt for the rebound, where the worn leather that had just left his fingertips suddenly smarted the side of his face, evoking pain that spanned beyond the physical and acute.

“It’s alright; try again.” He heard his father’s voice from across the gym.

“I’m not trying that again!” Drake responded, astounded.

“Try again,” his father interrupted, “You’ll be okay.”

Drake had just experienced a painful realization that most of us only know in our nightmares – one that would shape the course of his life for years to come. He had opened his eyes that morning to find that he was completely blind.

“The last thing I remember seeing was my dad when I went to hug him goodnight. I had suffered from amnesia for about six months, and I woke up the next morning having completely lost my sight.”

Drake suffers from an unusual case of cortical blindness, a type of vision loss that normally occurs due to damage in the brain’s occipital cortex. Doctors remain mystified in regards to Drake’s particular case that is accompanied by hemispheric migraines. They are unsure of the specific cause for his complete loss of vision at age fifteen.

“That first day [of being completely blind] my dad retaught me how to shoot a basketball and get my own rebound. As an adult, I look back on moments like that and realize that those were the best moments I could have ever had. We learn from our failures. Those stumbling blocks weren’t bad things; they were great learning and teaching moments.”

With his father as his swim coach, Drake had been training and competing in the water for close to six years at the onset of his blindness.

“My dad played a huge role in everything. I remember him telling me, ‘You’re blind, and that’s okay, but being blind doesn’t give you can excuse to give up on life.’ He was right.”

Immediately after losing his sight, Drake faced the inevitable reality that he would need to relearn a sport that had played an integral role in his life since age nine.

“It was frustrating, but I had a choice. I could either cry about what I didn’t have, or I could go for it. If I focused on all the the things going wrong in my life, I would be a really sad, depressed person. I had to learn to smile and trust that it would all be okay. It was. I had a plan that I didn’t understand at the time, but I look back and see that everything has worked out for me.”

That plan didn’t unfold without obstacles, however, as Drake proceeded to learn how to compete in his sport as a blind athlete.

“His first practice back, he didn’t swim all that much,” Drake’s father, Shawn Drake, remembers. “His team was just so excited to have him back. Everyone was questioning him; they were curious and just wanted to make sure he was okay.”

That initial day marked the beginning of a brutal and beautiful journey, as Drake tried to navigate the sport he so loved through trial and error.

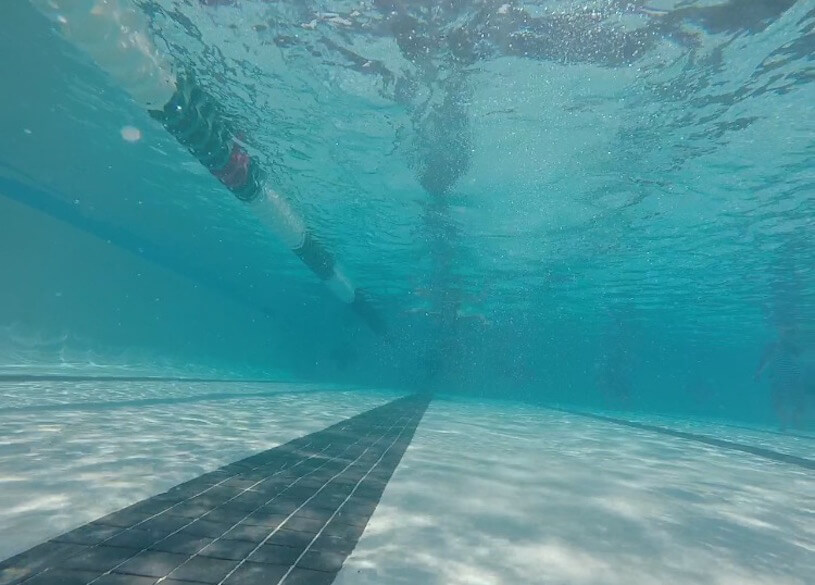

“As it went on, I had a lot of teammates that helped make life easier, some more patient than others,” Drake recalls. “I can remember swimming down the lane and losing the lane line. I eventually crossed over to the opposite rope, where one of my friends grabbed me by the shoulders and said, ‘Hey watch where you’re going; you’re on the wrong side again.’ It was all about patience, but swimming soon became an outlet for me to just be me. It never really changed for me even after going blind. It was a place where I didn’t have my cane, where I still did what I always had.”

Drake and his father quickly began to research the blind swimming community, becoming persistent in learning and adapting their training to maximize Drake’s potential, regardless of his disability.

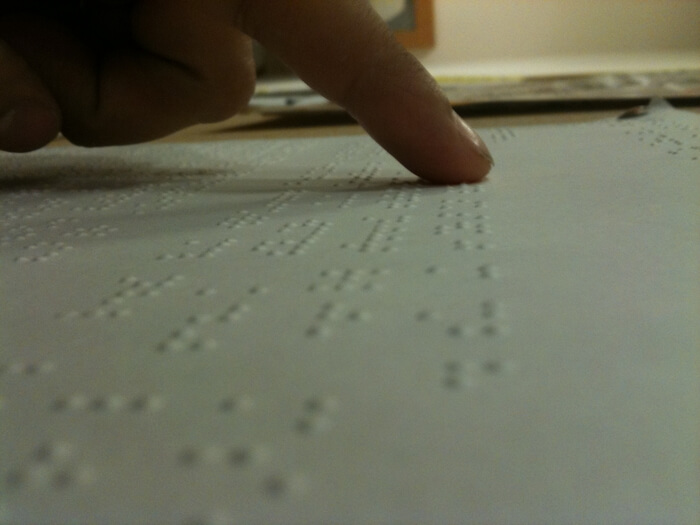

“We grew and learned together; sometimes we learned the hard way,” Drake laughs. “We learned about tappers. In my first tapping experience, they hit me with the cane I used for walking with nothing soft on the end. It was all about navigating this new chapter in my life and figuring things out.”

As years went on, the duo broadened their knowledge and polished their routines, eventually seeking every advantage in order to advance to the next level of competition.

“We asked ourselves, ‘What are some things all other blind athletes do?’ They follow the lane line. How do we get off the lane line? That took me years to learn, but now I can do it. I compete down the middle of the lane.”

With this attention to detail, Drake found himself competing at the elite level in Para Athletics. Despite qualifying for prestigious competitions a few short years after losing his sight, Drake was met with his own set of disappointments, missing the 2012 London Paralympic team by one spot.

“I always joke that I got a hat, a bag, and a drug test out of that experience,” Drake remembers. “But that was my wake-up call. I decided I was tired of being the bubble guy – the last person to make a team or the first one to miss the team.”

The same night the 2012 London Paralympic team was announced, Drake returned to his hotel and applied immediately to train at the Olympic Training Center, where he practiced for close to five years.

Shifting his focus to the 2016 Rio Games, Drake followed a rigorous training regimen under the tutelage of experts in the field. The World Championships of 2013 brought another set of disappointments, however.

“I took two fourths, a fifth, a seventh, and an eighth. That fourth place was a hard moment. There I was again.”

In true form, Drake repackaged his perceived failure as a source of motivation, returning to the Olympic Training Center. With hard-nosed persistence, he began to whittle away at his Olympic dream, bringing home a silver and a bronze from the 2014 Pan-Pacific Games and dropping more time in the 400 free.

The 2015 World Championships soon approached, a competition Drake predicted would be indicative of his performance at Olympic Trials.

“I remember an athlete on my own team telling me that I was bound to take another fourth place in the 400 free. That’s what I did,” Drake recalls. “But I also remember getting [to the World Championships] and hearing all of those voices of doubt, and then I thought, ‘Really, the only person who can tell me I can’t is me.’”

In his preliminary 400 meter freestyle, Drake was initially disqualified for failing to touch the wall. After reviewing the call, the officials reversed the disqualification. Drake entered finals seeded in fourth place.

“I got so excited to swim that race, I lost count. That’s where I earned the nickname Mr. 500. The last 50 of my 400, I had to make the decision to either turn or finish once I felt the tapper. I turned,” Drake laughs, “But I took home bronze in the 400 and a silver in the 100 meter breaststroke.”

Drake’s World Championship was only a precursor to the success he would experience at Olympic Trials, where he won the 100 meter breaststroke on the first day while simultaneously harnessing the American record. Following up with a fifteen-second drop in the 400, Drake solidified his spot on the United States Paralympic team, a peak moment in his career.

In Rio, Drake continued to achieve, taking silver in his first event – the 400 meter freestyle – by barely out-touching Brazil’s top seed. With soaring confidence, he entered his second event, the 100 meter breaststroke.

“I just knew that I was going to win that race,” Drake recalls. “I thought, ‘Today will be the day.’ And then I ended up with another silver. I remember my now wife, Paula, asking me to shake my medals, and I took that second silver, gave an unenthusiastic ‘tink, tink,’ and put it back in the drawer. At that moment, it was just another silver to me. That’s when Paula taught me one of the most important lessons of my career, and that was to be happy with what I have but never content.”

Photo Courtesy: @usparalympics Instagram/Getty Images

It was then that Drake decided to really test the boundaries.

“I came back from Rio, and I sat down with one of my friends at practice. I said, ‘Tell me what you see, and I’ll tell you what I hear.’ At the Olympic Training Center, I started asking coaches what the swimmers were doing, and I tried to piece together different splashes. I asked what it would take to become a coach, and they told me I could always volunteer. No one would be crazy enough to hire a blind coach; that was an impossibility. Then, I heard about Catawba College.”

Drake sent an email to Head Coach Michael Sever of Catawba College, located in Salisbury, North Carolina, to inquire about the assistant coach position.

“I told him if he needed an assistant coach, if he needed some help, I’d be interested. I said that I was only blind, and I could use all my other senses to coach.”

Sever emailed back immediately, setting up a phone call with Drake as soon as he returned from his team’s conference meet.

“We talked for an hour and half when finally he asked me, ‘How are you going to coach?’ It was simple; I could use my hearing. In swimming, we are always looking for something new: for a different angle. Sometimes I even think it’s an advantage to not rely on your eyes for feedback. When someone enters thumb-first, it sounds like a cannon ball. I can correct someone’s catch in this way. Since then, I’ve had other coaches come out and try to learn how to analyze the audio of a race.”

Coach Sever hired Drake, introducing his new assistant coach by first showing the team a video of Drake’s record-breaking 100 meter breaststroke. After asking them about the possibilities and impossibilities that would come with having a blind swim coach, he presented a personal video of Drake speaking to the team, telling them of his excitement and how he planned to to enrich their swimming experiences.

“It was awesome,” Drake says of being hired onto the Catawba staff. “Of course I was nervous, just like any new assistant coach would be. I could tell that the blindness was in [the team’s] minds, but no one wanted to say it. I remember the first time I called someone out on hand position, then I called out another person for tugging on the lane line. I could hear the breathing pattern change – the way in which they were astounded. Now, they don’t even think about it. They come up and ask me what I heard in their swims.”

Despite beating all odds, Coach Drake views his own success as puny in comparison to his long-term goals. While he hopes to continue inspiring the athletic community with his story, he longs for the day when athletes can grow into any profession regardless of ability, disability, or difference.

“I can’t wait for the moment when a blind coach is looked at as just another coach. I want people to know that you can do whatever you put your mind to, as long as you’re willing to think outside of the box and take that word ‘impossible’ out of your dictionary.”

Wow, just wow! Very emotional story. Gives you a different perspective of life.

Another great piece, Taylor! I always get excited when I see your name pop up, you never let us down! Another truly inspiring story giving us perspective. Keep up the good work!

Taylor, I have read and listened to many articles and interviews about my son; and this is one of the best. Thank you for doing such a great job.

Very moving commentary on life circumstances, and conquering obstacles in such a determined manner. Mr. Drake well done. Excellent work Ms. Covington. I see you are an intern, I see a great future for you, should you pursue a writing career.

Well written, heart felt article. Look forward to reading your next one.

awesome article, very well written!!