Swimming Without the Black Line: How Blind Athletes Adapt

Swimming Without the Black Line: How Blind Athletes Adapt

This article from the Swimming World archive, written by Paralympian McClain Hermes, details the approaches used by visually impaired swimmers.

By McClain Hermes, Swimming World Intern

When I began swimming at the age of four, I told my parents that I wanted to go to the Olympics. As I grew older, my eyesight slowly began to deteriorate. At the age of eight, I had several eye surgeries that unfortunately resulted in the loss of vision in my right eye. Over the next several years, I would slowly lose the rest of the vision in my left eye, eventually, leaving me blind.

Photo Courtesy: Matt Hermes

As my vision decreased, it became harder for me to swim. My place of refuge had turned into an unsafe environment. I would often run into the walls and hit the lane lines. At this point, I thought that my dreams of being an Olympian were over. I am not one to give up, and with the help of an understanding coach, I turned my sights from being an Olympian to becoming a Paralympian. The Paralympics are the parallel of the Olympic Games but for elite athletes with disabilities.

Photo Courtesy: Matt Hermes

Now at 19, I can say that I accomplished the goal that I set out to achieve at the age of four. I competed in the 2016 Paralympic Games where I finished eighth in the 100 backstroke. I went on to win five medals at the 2017 World Championships and became the world champion in the 400 freestyle. Over the years I have set more than 20 American records and held the world record in the 1500 freestyle. (Read this article by former Swimming World intern, Molly Griswold, to learn more about my swimming journey: Finding Freedom). Even though I went from being a fully sighted swimmer to a blind swimmer, my athletic goals never changed.

Paralympics

When I was introduced to Paralympic swimming, I met athletes with all types of disabilities. I was finally able to compete against people who were blind like me. In Paralympic swimming, there are 14 different classifications. Classes s1-10 are for swimmers with physical impairments, s11-13 are for those with visual impairments, and s14 swimmers have an intellectual impairment. I am now able to swim against athletes who have a similar disability to mine. This makes competition fairer and more equal for the competing swimmers.

Photo Courtesy: Matt Hermes

Each classification has its own unique set of regulations and these are administered by the Paralympic Committee. The following paragraphs will explain the differences in the vision classifications, and comments by a few of the athletes who compete in these events by telling how they adapt the sport of swimming for their visual impairment.

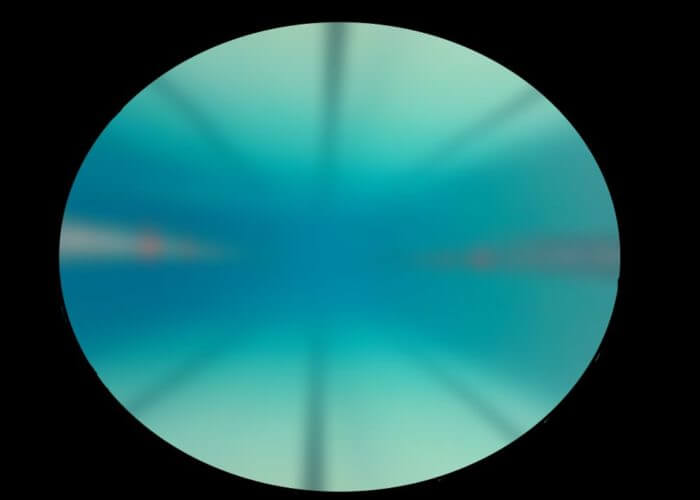

To help understand the different levels of visual impairment in athletes who compete in Paralympic swimming, we have a base photo of a swimming pool that a person with normal vision would see. As we go through the different classifications, the image will change to reflect what the swimmers in the classification might see.

S11 Classification

s11- According to World Para Swimming, “These athletes have a very low visual acuity and/or no light perception.” Swimmers in this classification must wear completely blacked out goggles and use a tapper while competing.

Photo Courtesy: Matt Hermes

When I swim, I wear completely blacked out goggles. I cannot see anything. I must feel my way to the block and set myself for the event. I cannot see my competitors, the clock and certainly not the black line at the bottom of the pool which is there to guide most swimmers. Once I dive in, to stay straight in the lane I trail the lane line with my fingers as I take a stroke. This works for the most part, but sometimes I get off path and zig zag across the lane. Trailing the lane line has also caused cuts, scrapes, and sometimes even jams to my fingers.

To keep track of intervals, I set a tempo trainer to the interval and when I hear the beep of the tempo trainer, I go.

During practice I count my strokes to know when I am getting close to the wall. I also use a simple garden sprinkler set up at the end of the lane. When I feel the water from the sprinkler, I know that I am approaching the wall. The water from the sprinkler combined with my stroke count, allows me to be able to flip turn during practice.

In competition, I use an object called a “tapper.” My coaches, parents, or teammates stand at the end of the pool and tap me on the head with a long pole with a tennis ball attached to the end. Each blind swimmer has a different opinion on how and when they prefer to be tapped, but I like to be tapped on the head one stroke away from the wall. Using a tapper requires a great deal of practice and trust on my part. I need to trust that my tapper will be there and will tap me correctly. Without that trust, I am unable to swim at race speed.

S12 Classification

Photo Courtesy: Matt Hermes

s12- World Para Swimming says that s12 athletes, “have a higher visual acuity than athletes competing in the S/SB11 sport class and/or a visual field of less than 5 degrees radius.”

Becca Meyers

Photo Courtesy: Becca Meyers Instagram

Six-time Paralympic medalist Becca Meyers has Ushers Syndrome. She has experienced a progressive loss of her hearing and vision. Meyers has also had to adapt her swimming for her visual impairment. She says, “As a visually impaired swimmer, I have adapted to swimming in the pool by following the black line and counting my strokes. I still have a little bit of vision where I can make out the T on the bottom of the pool and when I approach the T, I know the wall is 3-4 strokes away and then I flip.”

Meyers also uses a large, bold, green pace clock at practice so she can keep track of her intervals when practicing alone.

Jenna Jones

Photo Courtesy: Jenna Jones Instagram

Australian Paralympic swimmer, Jenna Jones says, “I adapt my swimming by counting my strokes and underwater kicks during practice. I usually just see how it goes when counting strokes and I sometimes run into the wall.”

Jones, who competed at the 2016 Paralympic Games, uses a tapper during competition so that she can have a more accurate flip turn. This helps her focus on her race rather than focusing on when she needs to flip turn.

S13 Classification

Photo Courtesy: Matt Hermes

s13- As a s13 swimmer, “Athletes have the least severe vision impairment eligible for Paralympic sport. They have the highest visual acuity and/or a visual field of less than 20 degrees radius,” according to World Para Swimming.

Colleen Young

Photo Courtesy: Colleen Young’s Instagram

Rio 2016 Paralympic bronze medalist, Colleen Young, has albinism. This causes her to have a visual impairment making it difficult to see in the water especially with her light sensitivity. Young says that she adapts her swimming by, “(trying) to stay focused on the black line at the bottom of the pool to lead me forward. Because of my condition it’s hard for me to swim in a straight line so I found that following the black line helps me not drift as much in the water.”

Madeleine Babcock

Photo Courtesy:

Madeleine Babcock, a 16-year-old visually impaired swimmer, chooses different techniques to adapt swimming for her limited vision. Babcock said, “I use the lane line to stay straight and not run into everything. I also ask a teammate to tell me when they are leaving the wall so I know when to go.”

Photo Courtesy: Madeleine Babcock

Due to a lack of depth perception, Babcock cannot tell how far away the wall is from her. During practice Babcock sets up a pool light at the “T” on the bottom of the pool so that she knows when she needs to flip turn. At swim meets she also uses the tapper to notify her where the wall is.

Blind swimmers are some of the most adaptable athletes in the world and use a variety of devices and techniques to keep themselves safe and on track while swimming at practice and during times of competition. Even though there have been concussions, bruises, broken fingers, and various other accidents, vision impaired swimmers continue to show their love for the water by doing whatever it takes to try to swim that black line to victory.

Great article. Thank you!

My college (Western Illinois Univ.) hosted the Blind Nationals 3 out of the first 4 years it was held. I worked Nationals, then was a volunteer for the 1980 blind Paralympic training camp at WIU.

I worked with all the blind swimmers, including the great Trischa Zorn, who won 7 gold at that Olympics, and went on to win 53 total Paralympic medals (37 gold, 10 silver, 5 bronze) in 7 Paralympics.

She qualified for the sighted 1980 Olympic Trials in backstroke, was a H.S. All-American at Mission Viejo, and was the first visually impaired athlete to be awarded a Division I scholarship in any sport.

She knew her stroke count for all her strokes for 25 yards. and 50 meters, so she knew where the wall was.

YOU HAVE BEEN AN INSPIRATION TO MANY…SINCE IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO KNOW JUST HOW MANY,,,ITS JUST LIKE TRYING TO COUNT ALL THE STARS IN THE NIGHT SKY…YOU CANT COUNT THEM,,,BUT YOU KNOW THEY ARE THERE..KEEP ON INSPIRING PEOPLE..THANKS, AND MAY GOD BLESS.

Very informative article, McClain! Great use of the visual examples of what those who compete within different classification might actually perceive/see! So proud of you and of all the things you’re accomplishing in your life! ??????

McClain, you are an amazing writer and athlete. I absolutely love the visuals in the article- so informative, especially for those who don’t know much about the classifications. Can’t wait to read more of your articles, you are the best!

It is great see blind people swimming is achieved for them ??????

Well done, McClain!

So proud of you!! Don’t stop believing!

????

McClain,

I just saw this today…a wonderful article, very informative, great use of pictures. Good for you! One question tho….I don’t know what “intervals” are. Is that the timing between each stroke?

Wish we saw more of you….

Love, Gigi.