Swimming Away from an Eating Disorder

By Cassidy Lavigne, Swimming World College Intern

“50 recovery!” our coach would say as we try to catch our breath on the wall, our muscles heavy from the last set. It was the second best thing to hear at practice besides “last set of the day.” We could reset our body. We could breathe again without it burning our lungs. I would tilt my head back and take a deep breath in before pushing off the wall into slow backstroke, inhaling in the cool night air. My body slowly began to feel normal again as the lactic acid left my muscles.

I never questioned when my coaches said “recovery” at swim. I was grateful for it. But when I needed to go into recovery for my eating disorder, I dug my heels in the ground. If I was so happy and accepting of the fact that your body needs recovery to reset during a workout, why was I so against it when I needed to get help?

I remembered reading about eating disorders for my psychology class. Research shows eating disorders and disordered body image exist more commonly within sports which require athletes to don more revealing uniforms. It listed swimming as an example. I was in denial about this fact. Already several of my closest teammates had approached me, “This is getting out of control…” When my mother started to notice how I restricted my calorie intake so severely, she commented how she “didn’t want me to become anorexic.” I had lost 20 pounds in a month simply by cutting my calories and carbs. Most of what I lost was muscle.

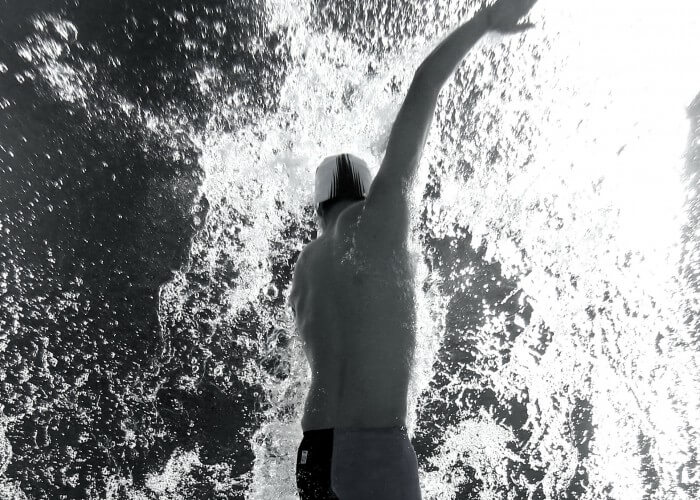

Photo Courtesy: Xinhua/Ding Xu

My situation was different with swimming. In fact, I found myself least worried about my body when I was in my swimsuit. The pool was a quiet place where my disordered thinking didn’t loom, even when it was at its peak of aggression. It was after bad races and practices that the disordered thoughts intruded, and they stuck with me for every meal that followed after not performing to my best.

I looked in a mirror, lifting up my shirt. I saw the food. My stomach was bloated. I saw that brownie I had after dinner. I saw the piece of toast I had for breakfast. My arms weren’t small enough. My collar bones weren’t protruding. I was fatter than I was this morning after a workout, and on empty stomach.

I didn’t want to get help for myself. No matter how many of my friends, trainers, and family came up to me with their concerns, I shrugged them off. I didn’t take my issue seriously, so I didn’t take them seriously. It wasn’t until I was warned by a nutritionist that the way things were going would prevent me from swimming.

“You’re nearing a cliff that has a severe drop. You’re close to crossing that line. You won’t swim faster if you don’t fuel your body. You won’t even be cleared to swim.” I began to realize the road I was going down– I wouldn’t get faster or be able to swim. If I wasn’t going to recover for myself, I would recover for my swimming.

The way eating disorders exist within athletes makes recovery complicated. Athletes have to fixate on their bodies differently in order to perform their best in their sport. Already we are aware of how we need to fuel our body correctly with the right foods. Extensive periods of training add to this complication, because of how closely the focus of the sport aligns with the fixation of an eating disorder. However, athletics and swimming can also help lead to the road to recovery and, like me, can even pull you through it.

It started with getting on a meal plan, which included eating a small snack before practice. At first, I didn’t attribute my strength to eating a snack. I was simply doing what my meal plan said and what the paper said. When I had bad days of disordered thinking, that bad turn off the wall, I blamed having too big of a meal.

But then I noticed the energy I had at practice. Afterwards in the locker room, I would think about how strong I felt during hard sets. What once felt like “giving up” because I was eating something between meals now made me realize how much better I performed at practice when I ate beforehand. This encouraged me to continue recovering, and to fuel my body so it could perform at its best.

Being in recovery doesn’t mean that I never have bad days, when unhealthy thoughts sneak in. But it does mean that I have the tools and strength to overcome these thoughts. Whenever I feel myself slipping into these disordered thoughts, swimming is, and always will be, there to catch me.

All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine nor its staff.