Sun Yang Vs World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA): A Detailed Analysis From CAS Arbitrator

Sun Yang Vs World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)

LawInSport, of Melbourne, has published a detailed analysis of the Sun Yang Vs World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) hearing by a Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) arbitrator.

The article, by Jack Anderson, sets out the key arguments of both sides of a case that could end the Chinese Olympic champion’s career or put him back on the blocks on a collision course with rivals who think he should not be in the pool come the Tokyo 2020 Games.

Anderson, who was appointed as an arbitrator to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in 2016, sets out the strengths and weakness of argument for and against WADA’s case for appealing a FINA Doping Panel decision of January 2019. The Panel handed Sun a severe caution but imposed no penalty after hearing of an acrimonious four-hour dispute with out-of-competition testers near the swimmer’s home on the night of September 4-5, 2018.

The visit ended with no urine sample being produced and the blood sample that had been provided and signed for being removed from the chain of custody. A glass container in which the blood sample was housed was smashed with a hammer on the pavement outside the control room.

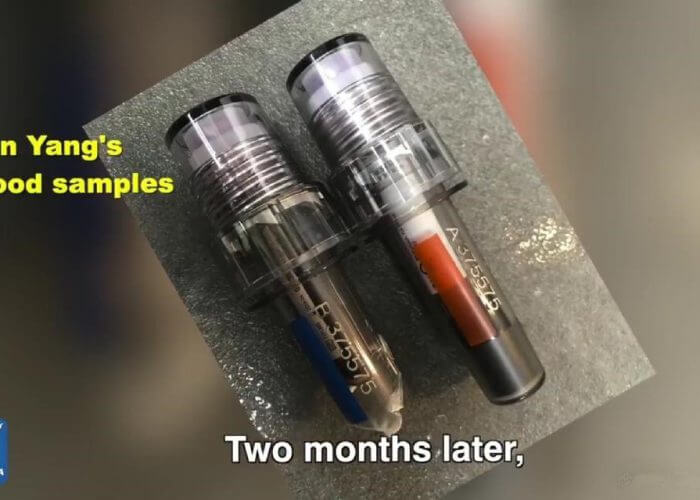

There remains a lack of clarity on what actually happened to the blood sample. While the FINA Doping Panel report and subsequent media reports suggest the sample itself was smashed, others say that only the outer container housing the sample was smashed but the inner container and its blood sample survived.

Photo Courtesy:

Images released by Chinese media this week (right) and said to have come from Sun’s entourage, show two complete units. A divided sample is suggested by the caption reading “Sun Yang’s Blood Samples … two months later”. One container is intact, with blood visible inside the inner and outer housings.

The other sample container appears to be the sample that was smashed with the hammer by Sun’s security guard under instruction from Sun’s mother, Ming Yang, and under supervision of the swimmer: it shows an outer housing smashed.

If the images are indeed those of the Sun samples from September 4, then two significant questions arise:

- was the blood sample, inner container, smashed too, or removed?

- how would Sun have ended up with both outer containers pertaining to his blood sample(s, split in two) on September 4, given that the key argument of the Doping Control Officer on the evening in question, according to Sun’s entourage in their witness statements, was that she must retain the outer container for return to the IDTM agency and FINA custody, as evidence to what had happened? Statements suggest that Sun and team argued that they could smash the outer container, remove the inner blood sample and return the outer container to the officer. From the images as shown in the Chinese media, and assuming they are authentic images of the real samples, Sun and his team retained all elements of the evidence.

Anderson’s report at LawInSport, appeared on the same day Chinese media reports suggested that the entire CAS hearing would be heard again because the arguments of Sun and his entourage had not been given a fair hearing. Swimming World has asked CAS for comment and will add any response we receive to this file.

Since the hearing in Montreux on November 15, a stream of Chinese media reports, many of them generated by Xinhua, the national news agency, have focussed on the three Chinese testing officers. Changed testimony, witnesses being placed under immense pressure and decoy headlines such as “tester was a construction worker” have been a part of the mix.

Sun Yang and his counsel, Ian Meakin – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

In Montreux, WADA Counsel Richard Young referred to “concerns over intimidation and protection issues”, while his co-counsel Brent Rychener highlighted several times in cross-examination of witnesses the threats and warnings, as he described them, made by members of Sun’s entourage to the testing officers, including exchanges involving the swimmer’s mother, the head of the Chinese Swimming Association and two doctors, namely, Dr Ba Zhen, a man twice-penalised by WADA in 2014-15, and Dr. Han Zhaoqi, head of the Zheijang Anti-Doping Centre.

Dr. Han also serves in two other key capacities relevant to the case: he is the chief doctor at the hospital where Dr Ba works and recently won a prize as the head of Sun Yang’s “Scientific Team”, such links making his status as an anti-doping official less independent than it may appear to be at face value.

Issues of intimidation and potential conflicts of interest on the edge of the case are not considered in Anderson’s fine analysis of the legal arguments of both Sun Yang and WADA and the views expressed and questions asked from the top table of three judges hearing the case in Montreux on November 15.

Comment: In his analysis, Anderson balances out the arguments for both sides. If there is one imbalance to be found in the comprehensive assessment it is where the weight of fairness to Sun Yang is set against the need for fairness to be applied to the situation of testers and the testers themselves. Those two things are not directly comparable, the status of athlete and testers on any anti-doping mission clearly apart and requiring cooperation on both sides in a control room in which the Doping Control Officer is supported to be in charge of proceedings. It can quite easily be argued that Sun’s entourage simply did not allow the DCO to either conduct her work as she intended nor, argues WADA, did they even allow her to finished statements intended to advise the athlete that he was at serious risk of non-compliance.

While Anderson does a fine job explaining that aspect of the case and how it applies in law, he also describes that facet in these terms:

“Sun Yang argues that while doping liability strictly applies to him, doping procedure only loosely applies to his testers, which cannot be fair or right.”

Sun Yang, with his counsel Ian Meakin to the left, in Montreux at the CAS hearing – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

The word loosely and the general intention of the sentence sum up a FINA/Sun argument hotly contested by WADA counsel in Montreux: the guidelines and the actual legally binding and applicable rule are in common use, well understood and long in use without any objection from the likes of FINA, the regulator now arguing against the very conditions it has agreed to on many thousands of occasions..

Further, Anderson states:

“In de Bruin, one of the testers said that she felt like she was “on trial”… ; in the Sun Yang hearing not all of the testers testified and those that did, did so in private.”

That summary lacks any mention of the “intimidation and protection issues” raised by Young and Rychener and significant in the general discussion about the tole of witnesses and whistleblowers and the need for the anti-doping system to offer such people the protection fairness would demand.

The Author of the Detailed Analysis

Jack Anderson is a Professor and Director of Sports Law Studies at the University of Melbourne. He is published widely on matters of sports law and contention, including monographs such as The Legality of Boxing (Routledge 2007) and Modern Sports Law (Hart 2010) and edited collections such as Landmark Cases in Sports Law (Asser 2013) and EU Sports Law (Edward Elgar 2018 with R Parrish and B Garcia). He was Editor-in-Chief of the International Sports Law Journal based at the International Sports Law Centre at the Asser Institute from 2013 to 2016.

Last year, Anderson was the sole CAS arbitrator at the Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast, Australi, and in this year was appointed to the International Tennis Federation’s Ethics Commission. He is currently chair of the Advisory Group establishing a National Sports Tribunal for Australia.

And here are the results of a Swimming World Poll asking readers to provide their opinion on what kind of penalty, if any, Sun Yang, who tested positive for a banned substance in 2014, should face. The overwhelming choice – 69% – was backing for WADA’s call for the swimmer to be served a suspension of between two and eight years.

Last week, Chad Le Clos and Sarah Sjostrom, the top two scorers at the European Derby of the International Swimming League, recommended lifetime bans for repeat offenders and those who fall foul of the highest category of offences under the WADA Code.