Stroke Wars: How Breaststroke and Butterfly Emerged As Separate Strokes

Stroke Wars: How Breaststroke and Butterfly Emerged As Separate Strokes

Today, we accept that there are four competitive strokes. But when the first rules for competitive swimming were written in the early 19th century, there was only one rule: Whoever swam the fastest from start to finish won the race.

The fastest “stroke” evolved from the breaststroke…to the sidestroke…to the overarm sidestroke…to the trudgen stroke…to the Australian crawl…to the modern stroke that we call, “freestyle.”

For variety at swim galas, event organizers staged competitions using the two basic strokes described in Monsieur Thevenot’s book, L’Art de Nager, first published in 1696. One was the traditional or “orthodox” breaststroke, and the other, using a similar technique, was swum on the back.

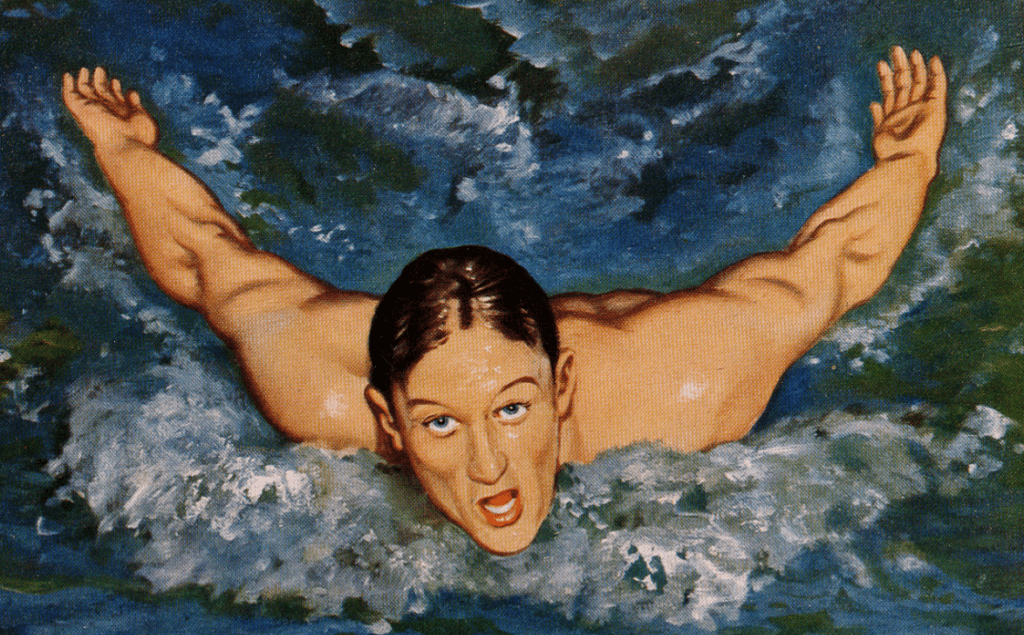

Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

By the time of the modern Olympics, what we know as the elementary backstroke had evolved into a back crawl, with the only rule, until recently, being the swimmer had to remain on the back the entire race. The rules for breaststroke were more complex. They required the body to be kept perfectly on the breast, with both shoulders in line with the surface of the water, and for the arm and leg movements to be simultaneous.

Since Thevenot’s day, the breaststroke began with arms stretched out in front of the head. With the palms turned out, the arms pulled wide until they were perpendicular to the body. The hands were then brought together and were pushed forward. The knees were drawn forward simultaneously with heels together. As the hands began the recovery, the feet kicked outward and backward, moving in a half-circle until they came together with a snap. This “frog-kick” propelled the swimmer forward. Although not a rule, the rhythmic sequence was “pull-kick-glide,” repeat.

In the 1920s, the quest for greater breaststroke speed led swimmers to begin experimenting with technical improvements. By the 1936 Olympic Games, there were three legal arm movements: the orthodox stroke; pulling past the hips with an underwater arm recovery; and the full underwater pull with an over-the-water arm recovery—or butterfly stroke. (You can see them all in one race by searching “200 Olympic Breaststroke 1936” on YouTube.)

Was the butterfly a technical advancement for swimming on the “breast”—as the Americans and Australians argued—or was it an entirely new stroke—as the Japanese and Soviet bloc nations saw it?

At the 1952 Olympics, all breaststroke finalists used the butterfly stroke, and it looked like the orthodox breaststroke would disappear as a competitive stroke. But after the Games, the FINA Congress narrowly passed legislation to split the breaststroke into two separate strokes: the “orthodox” and the “butterfly.” However, “if the IOC didn’t approve the additional event, the orthodox breaststroke would be the one that was swum.”

Since the IOC was looking to reduce the program, it was easy to believe there would only be one breaststroke race at the 1956 Games. However, the breaststroke-butterfly war ended when the Australians successfully lobbied the Melbourne Organizing Committee to add the butterfly as a separate event that year.

Bruce Wigo, historian and consultant at the International Swimming Hall of Fame, served as president/CEO of ISHOF from 2005-17.