Should World Records be Faster? Episode 1

By Tucker Rivera, Swimming World College Intern.

As we’ve touched on before, swimming is an evolutionary sport. Constantly improving, changing and growing in popularity, our sport has never seen a breadth of talent quite as wide as the one which it currently witnesses. That being said, some question whether we’ve plateaued in talent or whether our breadth comes from heightened participation rather than capability.

Two decades ago, the United States hosted its most recent Summer Olympiad in Atlanta, Ga. In just a decade from now, the United States will host its next in Los Angeles, Calif. This opportunity invites us to reflect on the past and anticipate the future of the sport. How much faster have we gotten? How fast can we expect to become?

In order to answer these questions, we’ll have to turn to the data. When comparing LCM times from the 1990s to our current world records and determining the average time dropped each year (1990s record set closest to the ’96 Atlanta Games), this article will attempt to clarify the above argument.

This series will be broken into episodes. This week’s theme: Sprinters.

Let’s take a look at how fast we were, are, and will become in the 100s of stroke and the 50 and 100 freestyles. If you’re a cheater and just want to see how fast people are going to be going in the L.A. Olympics, scroll to the bottom of the article.

100 LCM Breaststroke, Men

Photo Courtesy: FINA Doha 2014

In 1996, the world record wasn’t even under sixty seconds. Some were still swimming breaststroke without goggles at Atlanta; at a 1:00.60, the old world record wouldn’t have even made the A final at the 2018 Phillips 66 National Championships.

Since 1996, there have been 15 record changes in this event. With Roman Sludnov becoming the first man to break the minute mark, the 100 breast has changed markedly since his exit from the sport. Reaching all the way down to the current time held by Adam Peaty of Great Britain (57.10), the race has improved consistently and drastically since America’s last Olympiad.

However, this can easily be attributed to three things:

1. Adam Peaty is a monster.

Nobody can compete with the man, and nobody will be able to for many years. Michael Andrew, 19-year-old phenom and national champion in the event (and new 50 SCM American record-holder), is arguably the next heir to the breaststroke throne. Yet as of now, it seems that Peaty’s dominance is going to last for a long time.

2. The breaststroke pullout.

The breaststroke pullout is much different from what it used to be two decades ago. Changing first to allow a dolphin kick in the pullout and later to allow the dolphin kick to become separate from the pull-down in the 2013-14 FINA season, the way we think about breaststroke has completely changed. More energy can be conserved than ever before – the slowest stroke has become drastically more efficient. Pullouts now succeed 15 meters at the elite level and are significantly faster than they used to be.

3. Technology.

As we’ll see later in this article, technological advancements in the sport like “tech” suits and wedged blocks have greatly altered the means in which swimmers are able to compete. Starts, turns, and strokes are all supposed to be faster than they used to be. The sport has been designed for improvement, and athletes have actively taken advantage of this.

100 LCM Breast, Women

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

Also set in the Atlanta games, the women’s world record in 1996 was a 1:07.46. The current time? An unbelievable 1:04.13, currently held by the USA’s Lilly King. In the past 22 years, the record has been broken 12 times, marking a notable change in the 2007-2009 seasons, wherein American Jessica Hardy bested her own record by two seconds; she improved from a 1:06 to a 1:04 in just two seasons.

While this change may have been attributed to suit technology, recent success of swimmers like King, Katie Meili and Ruta Meilutyte suggest that breaststroke was going to progress regardless of the technological advancements. The record in this event has decreased consistently over time, if slightly less drastically over the past six.

100 LCM Back, Men

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

The fastest 100 backstroke in the ’90s occurred in 1999 with a mark of 53.60. However, success in sprint backstroke over the past two decades can be described in one name: Aaron Piersol. From 2004 to 2009, six of the eight new records were merely Piersol going a best time. The current record, held by Ryan Murphy, wasn’t set until many years after Piersol had hung up his cap and goggles.

The world record, 51.85, is only 1.55 seconds faster than the time set in 1999, largely due to the fact that backstroke’s rules haven’t been altered since the last time the U.S. hosted the Summer Olympics. Goggles, flip turns, and the 15-meter rule have all been in place since the early ’90s and have likely contributed to the race’s apparent peak and slower rates of improvement compared to breaststroke.

The 1999 world record would have placed fourth at the 2018 U.S. National Championships.

100 LCM Back, Women

Photo Courtesy: Swimming World

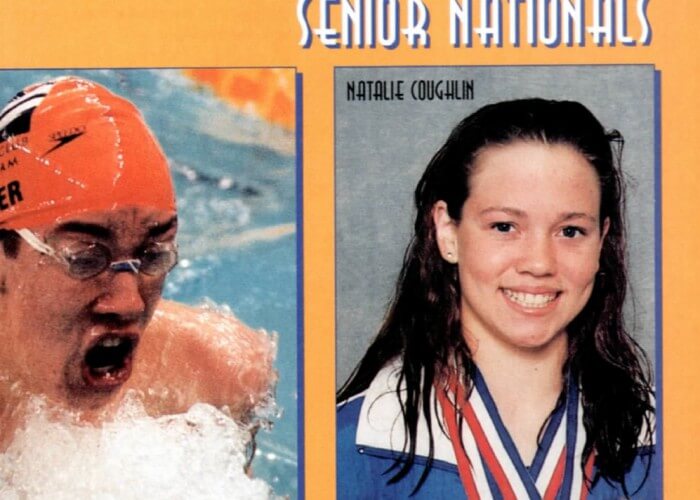

The slow progression of backstroke is even more evident on the women’s side of the event. After legendary backstrokers Kristina Egerzegi and He Cihong left the sport in the mid-90s, the top mark for a considerable amount of time was Cihong’s ’94 100 back that left the world aghast at her 1:00.16.

The next woman to approach that time ultimately became the first woman to break a minute in the 100 backstroke – Natalie Coughlin. A master of the underwater dolphin kick, Coughlin broke a minute for the first time in 2002 and didn’t go another best time until the just before the rubber-suit era in 2007. From 2007 to 2009, the record was broken eight times yet only twice in the previous 15 years combined.

After that, it took another eight years for Canada’s Kylie Masse to break the world record while racing in a textile suit; that mark was quickly bested by America’s Kathleen Baker the following year. Now at a 58.0, it seems that the 100 backstroke has finally caught up to the jump-start that it experienced in the rubber-suit era.

100 LCM Butterfly, Men

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

The men’s 100 butterfly was a wild ride. Obviously framed by the Ian Crocker – Michael Phelps rivalry, the world record battle in the 100 fly was highly touted. In fact, the record had been broken eight times in the ten years leading up to the World Championships in Rome in 2009. At these World Championships, Phelps beat his own best time (in a rubber suit) by four tenths of a second.

From ’96 to ’09, the world record was bested 9 times. Phelps, the first man to break fifty seconds, lowered the record to a 49.82 – a time 2.4 seconds faster than the mark that was set in Atlanta by Russian swimmer Denis Pankratov.

Nowadays, butterfly is edging on passing that record. Caeleb Dressel’s textile best-time is a 49.86, a time that is only four hundredths of a second slower than the GOAT’s best time in a rubber suit. It seems as if it’s only a matter of time before Phelps’ storied swim is taken off of the record books: the only question is by whom. Andrew, Jack Conger, Joseph Schooling, and Dressel (among others) all seem capable of besting that time in the near future.

100 LCM Butterfly, Women

Photo Courtesy: Maria Dobysheva

The year is 1981, and the East Germans are good at swimming. After a decade of their dominance in the event, American Mary T. Meagher becomes the foremost butterflier in the world. Dropping 1.33 seconds in just 16 months, Meagher set the world record in the 100 LCM butterfly at a 57.93.

Nobody would come close to touching that record for 18 years.

Broken in 1999 by American Jenny Thompson, the new record for the event was 57.88. Thompson’s time was quickly beaten by Dutch great, Inge de Bruijn, whose time wouldn’t be beaten until Sarah Sjöström in 2009. Sjöström wouldn’t beat her own time again until Kazan in 2015 before setting the current world mark at the Rio Games in a 55.48.

From 1981 to 2016, the world record only changed ten times and was broken by only 4 women.

While everyone seems to be getting faster at butterfly, Sjöström has evidently been better at improving than the rest of her peers. The depth in butterfly is steep, and some argue that this is because it’s not possible to swim the stroke much faster than it’s already being swum.

50 LCM Freestyle, Men

Photo Courtesy: SIPA USA

The 1990s were opened with Tom Jager becoming the first man to break 22 seconds in the 50 free. It wasn’t until 2000 that that record was beaten by Russian swimmer Alexander Popov, and it wasn’t until 2008 that anyone beat Popov’s record.

And then…

Out of nowhere, it seemed that any elite sprinter who wanted to beat the world record was entirely capable of doing so.

I give you the rubber era. In 2008 and 2009, the world record was broken six times by four men after only being broken once in the prior eighteen. Cesar Cielo (one of the largest men ever) topped out the record at a 20.91.

Yet since 2009, nobody has beaten the world record or even broken 21 seconds. As a comparison point, the fastest textile time ever recorded comes from Great Britain’s Benjamin Proud.

50 LCM Freestyle, Women

The fastest women’s time of the 90s was in 1994, set by Le Jingyi at a 24.51. The time was not bested until 2000 by Inge De Bruijn, was not broken again until the rubber era, when it was broken four times by four different women.

The rubber era mark wasn’t broken until 2017, when Sjöström went her blistering 23.67.

100 LCM Freestyle, Men

The fastest time for the men’s 100 free also came in 1994 when Popov went a 48.21. Nine record changes have happened since then, seven of which during the rubber era. The current mark, set in 2009 by Cielo (pictured below), stands strong at 46.91.

Photo Courtesy: Joao Marc Bosch

Many think that swimmers like Cameron McEvoy, Proud and Dressel are capable of breaking that record relatively soon, as McEvoy approached the record in 2016 with his textile-best 47.04 at the Australian championships.

100 LCM Freestyle, Women

Photo Courtesy: Delly Carr/Swimming Australia

If you hadn’t guessed it already, 2007-2009 saw a large time drop on the women’s side of the pool. While less stagnant in growth before the body-suit era, the world record for women was broken five times in one year, with Britta Steffen going five best times in the summer of 2009.

It wouldn’t be until July of 2016 that Cate Campbell would break the mark. The current record, held by Sjöström, is a 51.71.

Analysis

If you’ve scrolled to the end, congratulations – you’re in for a good ole’ fashioned summary.

- Because there have been so many alterations to the rules of breaststroke and breaststrokers (on average) are smaller than other sprint athletes, it is most consistently improved upon among the strokes. Breaststroke is the only stroke wherein both Olympic-length world records for men and women were set in textile suits.

- Men seemed to have made larger strides during the rubber-suit age than their female counterparts. Swimming in all facets has more depth than it did two decades ago; however, it seems that male sprinters haven’t quite caught up to the speediness of the sport’s golden age.

- Women sprinters seem to have benefited less from the rubber-suit era than men did; this has caused their data to be more consistent and follow a more natural progression of improvement.

- Sarah Sjöström is good at her job.

- The Dutch were and are fantastic swimmers. Please don’t forget about the Dutch.

- Yes, sprinters are faster now than they were 20 years ago, but not by as much as many may think. Sprinters will soon be widely capable of finishing races faster than they could have during the rubber era.

As promised, here are the predictions of how fast our times may become in the next decade. Utilizing the data alluded to in this article, we should be able to make predictions for the next 10 years by using regression modeling. Times wherein the current world record is that of a rubber suit will also include the current textile best time in the “world record” prediction statistics.

2028 LCM WORLD RECORD PREDICTIONS*

Photo Courtesy: L.A. 2028

Men’s 100 LCM Breaststroke World Record (2018): 55.83 seconds

Women’s 100 LCM Breaststroke: 1 minute 2.91 seconds

Men’s 100 LCM Backstroke: 50.24 seconds, with the first man breaking 50 seconds doing so in 2031.

Women’s 100 LCM Backstroke: 57.00 seconds

Men’s 100 Butterfly: 47.69 seconds

Women’s 100 Butterfly: 54.82 seconds

Men’s 50 Free: 20.63 seconds (20.71 seconds if we include the current textile world best-time)

Women’s 50 Free: 23.16 seconds

Men’s 100 Free: 46.04 seconds (more realistically, one might expect for the 2028 Olympics to be the first time we see a man break 46 seconds. We’ll have already been very close to the barrier; someone will have the will power to break it.)

Women’s 100 Free: 50.61 seconds (with the first woman to break 50 seconds, coming in 2033)

*These predictions assume that there will be no major rule changes in any of the four strokes within the next decade.

All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine nor its staff.

Regardless of opinions, training, coaches, or pools….a record will never be 0.000000.

Inane comment Ann,

A better yardstick to these predicted world records is how fast the records are becoming in the 50s of each stroke. With World Cup races all year round and World Records in the 50’s, elite swimmers are learning to swim faster more often. Many times the difference between the first 50 and the second is only slightly but they are going out much faster.

Caleb is over a full second faster than MP in the 50 fly, eventually the record could be under 49 seconds.

Male breaststrokers are closer to 2.5 to 3 seconds faster in the 50 Brasse now.