Roland Matthes: First an Idol, Then a Friend; John Naber Remembers His Guide and Pal

In a post on his Facebook page following the death of backstroke legend Roland Matthes, five-time Olympic medalist John Naber penned a beautiful tribute to a man that first was his idol and “guide in swimming,” and then became a good friend. John has given permission to Swimming World to reprint his tribute to Matthes, the double Olympic champion in the 100 backstroke and 200 backstroke at both the 1968 and 1972 Olympic Games.

****************

R.I.P. Roland Matthes, my guide in swimming

I have spent the last two days in shock and mourning over the news of the sudden death of my role model in Olympic sport, Roland Matthes.

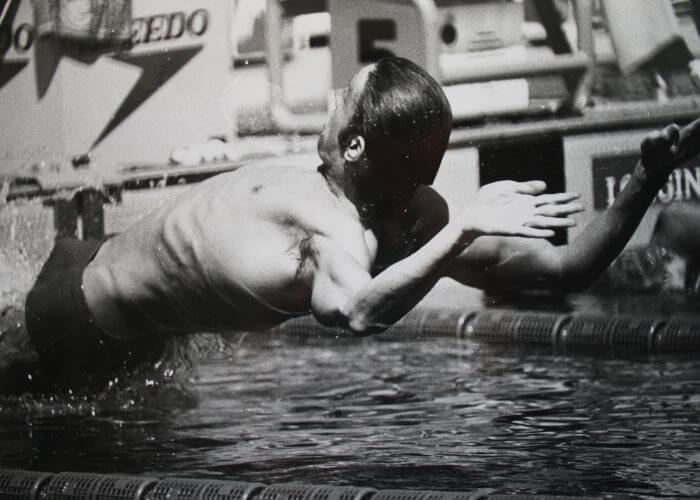

Roland was the greatest backstroker that ever lived. He is the only swimmer to successfully defend both Olympic backstroke titles, and he also won medals in international competition in freestyle and butterfly. Some say that only a slow reaction to the gun kept Roland from giving Mark Spitz the race of his life in the 1972 Olympic 100-meter butterfly final in Munich. Matthes was invincible on his back for a decade. His smooth strokes and powerful acceleration made every race I watched him swim become a foregone conclusion.

Like Bjorn Borg, the tennis star of that era, the long-haired Matthes kept his emotions to himself, reacting to world record victories the same as he treated lazy qualifying swims. Because he swam for East Germany, we assumed that he was being paid to swim with bonuses for world records. It even seemed that he could judge how fast or slow he needed to swim in order to break his own marks by the barest of margins. It was useless to try to “psych him out” with any sort of trash talk or other shenanigans. He seemed untouchable.

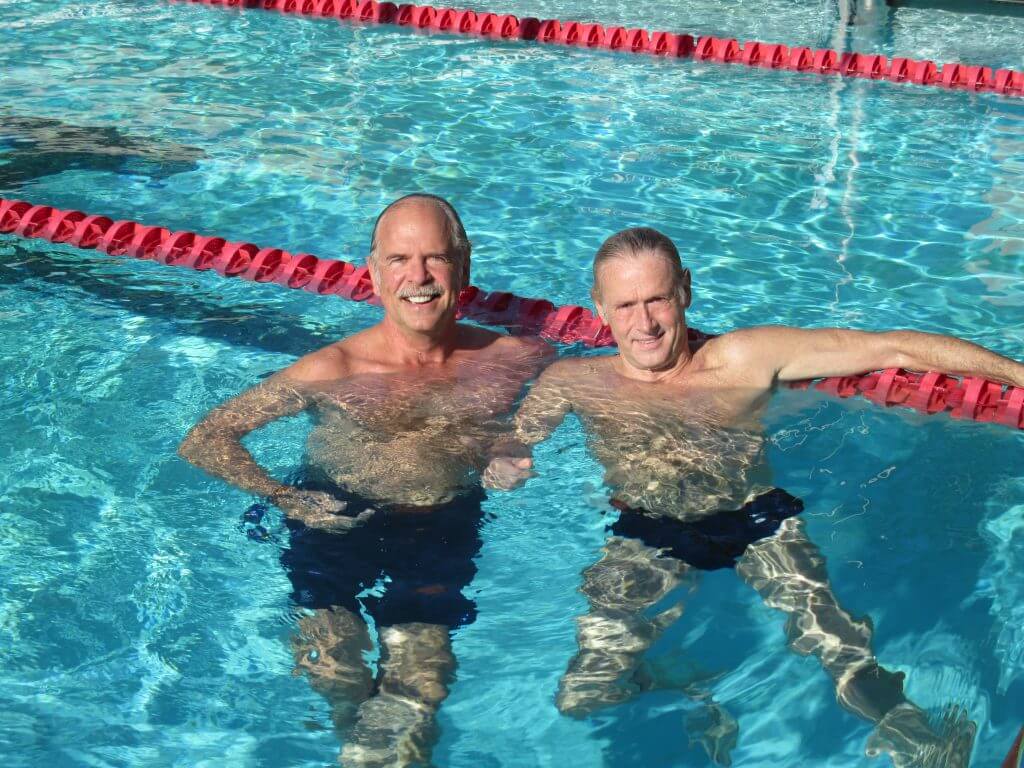

John Naber first saw Roland Matthes as an idol, but later developed a close friendship with the Olympic backstroke champion. Photo Courtesy: John Naber

Because Matthes rarely tried to speak English or befriend the American swimmers, we assumed he was a “Communist Party Animal,” loyal to the state and contemptuous of all things American. How wrong we were. He told me in 2016 that he seriously contemplated defecting while competing in California in 1974.

Backstrokers race while facing backwards, watching the field instead of the black tile line on the bottom of the pool. As we approached each turn, most swimmers would slow down slightly, in anticipation of the rapidly approaching concrete wall. At that precise moment, Matthes would pick-up his kick and drop in a couple of powerful strokes, bounce off the wall and rise to the surface, his lead now increased by two feet. When your opponent is two feet ahead of you in backstroke, they disappear from view. This was a magic trick that Roland mastered, while his opponents wondered, “How’d he do that?”

It has been suspected that the East German sports machine in the 1970s was regularly doping its athletes, giving them an unfair advantage against the world. Our evidence of wrongdoing included sudden, unexplainable improvements, wide emotional swings, chiseled-like musculature, acne between the shoulders, and (most evident in women) a lowered voice register. I saw none of these in Roland. In fact, years later, the German scientists who administered the program admitted that Roland’s coach had prevented any interference from the government in her club’s trading. Roland swam clean and fair.

For years, I used Roland as my guiding light in the pool. I devoured any articles about his training or diet. Information was scarce, but my imagination was constantly thinking about what he might be doing. I read that he would balance a shot put on the tips of his fingers and throw the heavy metal ball straight into the air, catching it with the other hand on its return, strengthening the muscles needed for the “snap” at the end of each arm pull. With every stroke I swam on my way to my eventual records, I’d imagine throwing that ball toward my feet, just like Roland.

Roland Matthes – Photo Courtesy: NTArchive

In the summer of 1974, the East German swimmers came to California for a USA/DDR dual meet, the two swimming superpowers meeting for a serious showdown. At that time, Matthes had been undefeated in backstroke races since April, 1967. I beat him in Concord, and unlike Borg, I could not contain myself. I was overjoyed and hopped all around the shallow pool. Matthes allowed me to hug him and he patted my head in congratulations. Like an elder statesman, he seemed to pass the torch with elegance.

At the Olympic Games in Montreal two years later, Matthes still held the world record in the 100 meters, and when I broke that mark in the semi-finals, he approached me with a smile in the warm-down pool, chucking me under the chin, saying simply, “Very fast.” It was the greatest compliment I ever received.

The following day, we met in the championship final with the gold medal on the line. The rules at that time allowed for false-starts to be charged to the field, and the disqualifications only occurred on the third such mistake. Backstrokers begin their race in the water, holding the starting blocks in their hands. In my entire career to that point, I don’t recall ever seeing any backstrokers false-start. Facing the wall, Matthes was on my right, and as the official called us to our marks, I noticed a flinch of motion a fraction of a second before the gun. Assuming the official also caught the movement, I lowered myself into the water, just as the field launched themselves backwards. After what seemed an eternity to me, the gun sounded a second time, recalling the field to the blocks. Had the race not been recalled, I would have looked like a fool hanging on the wall, and would have lost my first chance to win an Olympic title.

I noticed a little smile cross Roland’s face. He had done it on purpose, wisely trying to “catch a flier” and jump to an early lead. The crafty master had conceded nothing, and was going to use all his experience to win this race. The official called us back to our starting positions, and once again, I caught a flinch before the gun, but this time I joined the field into the pool, before the second recall gun sounded. For the third start, we were going to be “stuck to the wall,” because now any false starts would result in immediate disqualification.

The third time was a charm for me, and I was able to better my record and win the race. Matthes earned the bronze medal in his third Olympic Games, a remarkable achievement at the time, and his congratulations to me were both hearty and sincere.

I doubt that anyone watching their televisions in the United States was aware of the drama of that event, because ABC aired the race on a delayed basis, and did not bother showing any false starts. For me, what happened at the pool that day was as exciting as any race I ever swam.

Following his retirement from the sport, Roland elected not to “cash in” or benefit from his reputation, instead devoting himself to the service of others as an orthopedic surgeon. Like my other Olympic hero, the speed-skater, Eric Heiden, who won five individual gold medals at the 1980 Lake Placid Olympic Winter Games and shortly afterwards became an accomplished doctor, both these great Olympians never rested on their laurels, but continued to grow and challenge themselves. And both worked incognito as their national team doctors for the next generation of Olympic hopefuls.

As the 2016 Olympic Games were about to begin in Rio de Janeiro, I received an email from Daniela Matthes, his wife. She and Roland were coming to Los Angeles on vacation, and Daniela wanted to surprise her husband with a get-together. I jumped at the chance, and we nostalgically planned to go swimming in a nearby Olympic-sized pool. In Pasadena, he looked the same as I remembered, stylish, handsome, humble and graceful in the water. He had the same elegant mastery of his stroke, and his kick was still powerful, though he politely refused the opportunity to race. He had nothing to prove. His wife was his interpreter, though I could tell that Roland understood much of what was being said. He smiled at my jokes and nodded frequently, often with a thumbs-up sign. Dani was a charmer, herself a competitive fencer and a friendly and outgoing extrovert. She was the perfect vehicle to bring him out of his shell.

John Naber and Roland Matthes sharing a bite during a visit between the two backstroke legends and friends. Photo Courtesy: John Naber

Afterwards, they came by the house, and he willingly signed my personal Olympic flag, and we found ourselves on my living room couch, watching the Olympic swimming finals on television. Backstroke rules have changed a lot since the 1970s. Backstrokers now benefit from freestyle flip-turns and plastic wedges lowered into the pool to secure their feet for the slippery starts. Roland said he no longer followed the sport very much, so when I asked his opinion of the wedges, in his German accent, he said simply, “What will they do next? Give them all fins?” We laughed out loud, two old swimmers remembering our days of glory.

Roland and Dani were gracious enough to spend two more evenings with us, where two other Olympic swimmers, Bruce Furniss and Andrew Strenk were able to join our conversations. Strenk speaks fluent German and he was able to open the discussion into difficult or intricate subjects. It was there that Roland explained how he had always been aware that the state was watching his every move, which prevented him from being as open as he wished. He also admitted that the thought of defecting in the United States had indeed crossed his mind, but he did not want his family abused as a result. We posed for pictures beside the Eternal Olympic Flame at a book launch at the LA84 Foundation in Los Angeles. He patiently listened to 1976 US Olympic swimmer, Shirley Babashoff, as she spoke about her opinion of his East German teammates and his ex-wife, Kornelia Ender, and their state-sponsored cheating. I asked him afterwards how he felt listening to Babashoff, and he frowned a bit and said, “Uncomfortable.”

Though my wife and I were able to revisit Roland and Dani in Europe a year later, I consider their visit to California and that time on my couch as one of my most precious post-swimming experiences. The man who molded my career, the man I did not merely want to emulate but wanted to be, had become a dear friend, and in spite of our language and geographical and political distance, he was considering us as equals.

Roland passed away this week, far too soon, and I can’t stop thinking about him and his effect on me, and my sport. I know that some swimmers may eventually match his records, but no one will ever take his place.

My sincere sympathies go to Dani and my thanks for the fact that she brought us together one more time.

That was beautiful

Nicely said

Fantastic, beautiful piece. Love the detail. Can “feel..the-love”. Best, best…..!!!!

Well said and I’m still amazed by his graceful yet powerful stroke.

Great and well written story John. Roland sometimes was unfairly accused of wrongdoing because he was from the DDR and married to Kornelia Ender. But I think most swimmers from that era never thought once that he was cheating. From that era, he was one of the best swimmers in the world and was a role model for swimming. He will always be remembered.

Such wonderful words from a wonderful man. John was my idol and I was and still am proud to tell all of his greatness and of Roland’s who together paved my way into becoming an Olympian myself in 1980 (GB) when I swam in the 200 Backstroke final and also the 4 x 200 Free Relay final – just like John did in ‘76.

I read great things about the rivalry between Roland and John and am so glad they became great friends.

This is a wonderful, touching tribute from one of my idols in the sport…who in turn, had HIS idol in Matthes.

Rest in peace…

Thanks John!! Hope you are well.

My Captain, My Captain;

John, so thrilling, and sad, to read, hear and re-experience our lives through your words. My condolences to the Matthes family and yours. Those of us who are a Fish understand all. Every word, every nuance, every gracious moment, and every feeling you shared.

And more. Like a moment I don’t & won’t ever forget. 1996 Atlanta ( Olympics for forgetfulls) warmups just before morning qualifications. I’m early, sitting down at row1 watching and reveling in Big Fish time as I call it. You walk by and I see your still then mustache. I say hi John! You stop, turn and smile. “ who is this guy?, your thinking. We shake hands and chat for 3 seconds. You then continue. That’s all it took to share your entire Olympic career with me. 3 smiling happy seconds. I am forever thankful and still tell the story today.

It taught me humbleness and appreciation for the gift we have in the water and to share it and give it away. And having watched Roland swim before you, and then you win Gold. I always thought of him as a swimmer. Not someone from an Easten bloc country. Funny, isn’t it?

Your writing is an amazing, loving, come full circle part of my life. I am a Free and Fly sprinter. When Carter blew us out of Moscow 1980, my Ganes were done. As so many of my generation were in many sports There weren’t stipends or Corporate helping for a 25 year old like me without means.

Ask Bob Beamon. He can share with you that my passion to freely teach, share, give and give more to those who love the water will always exist.

Hope to see you in Tokyo 20. And I hope Don Schollander is going back too. 4 Golds in 1964 restarted USA swimming. “Deep Water”, Don. I have a signed copy.

I hope Don is reading this. Would love to see you all at Team USA House. I’m a fervent supporter of Team USA.

John. Thank you.

After all,

It’s Not Every 4 Years;

It’s Every Day.

My Captain, My Captain,

and to your friend, Roland,

God Speed.

Ben

I was sad to learn of Roland Matthes passing. I was an age group swimmer when Roland dominated the backstroke at the 68 and 72 Olympics. He had an aura of invincibility but without any arrogance. He was one of my swimming heroes along with Don Schollander and Mark Spitz. I had much respect for John Naber’s 1976 Olympic performance also. I feel sad that Roland passed away too early. My sympathies go out to his family and close friends.