Rising Distance Swimmer Michael Brinegar Following Family Path

By David Rieder.

More than 30 years ago, Jennifer Hooker was fresh off swimming at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal when she moved west to train with Mark Schubert and the Mission Viejo Nadadores. Three decades later, her son, Michael Brinegar, followed the same pathway, from Indiana out to Southern California.

“It was kind of a family thing,” Schubert said. “Mom has a lot of faith in me.”

It was back in 2015 when Schubert first suggested that Brinegar, then 15, come out and train with him at Golden West Swim Club for the summer. He returned the following summer and then moved out to California in the fall of 2016, following Schubert when the coach returned to Mission Viejo in October.

“We just kind of connected well,” Brinegar said of his relationship with Schubert. “I really like the practices he gives me, so I don’t know—it just worked.”

Yes, it worked. Uprooting his entire life and moving away from home as a teenager has paid off as Brinegar has become one of the top young distance swimmers in the country.

In 2017, Brinegar made a name for himself while swimming back in Indiana, at the IUPUI Natatorium—a pool in which he had been racing “since I was seven,” located less than an hour north of his hometown of Columbus, Ind.

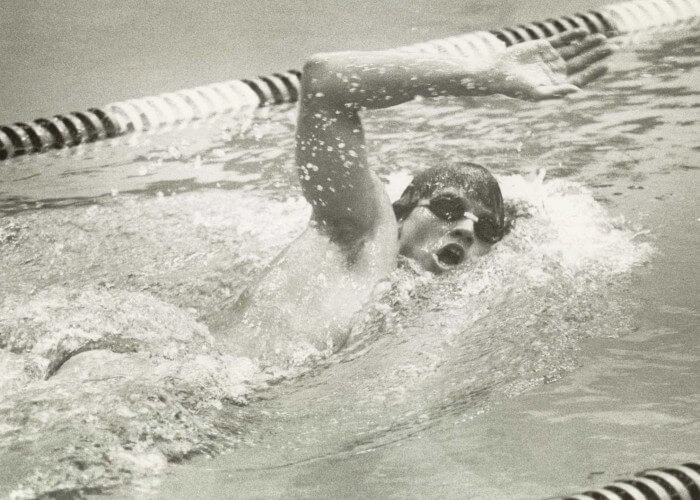

Michael Brinegar at the FINA World Junior Championships — Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

In June, Brinegar finished fifth in the 1500 free at U.S. Nationals. Two months later, he returned to Indiana for his Team USA debut at the FINA World Junior Championships, where he won a silver medal in the 1500 free and a bronze in the 800 free. He finished the year with lifetime bests of 15:09.00 in the 1500 and 7:57.22 in the 800.

This fall, Brinegar made the country take notice when he exploded in the 1650 free at Junior Nationals West, putting up a time of 14:37.71. That performance tied Brinegar with Robert Finke as the fastest high schooler ever in the mile.

The story behind that swim? Brinegar had slogged through a less-than-stellar meet to that point, so he made a request to Schubert that he scratch the 200 back and the 200 fly, scheduled for the same day as the 1650.

“He came up and said, ‘Mark, I really want to scratch these two events,’” Schubert recalled. “He knows how opposed I am to scratching events. We have a saying at Mission Viejo that ‘the Nadadores don’t scratch.’ I was about to say no, and then he said, ‘I want to break the record in the mile.’ I immediately caved when he said that.

“He said it so convincingly that I knew he could do it.”

The previous Junior Nationals meet record had belonged to Sean Grieshop at 14:45.40, and Brinegar blasted through not only that but the 14:40 barrier as well. Schubert had instructed Brinegar on how to compete against Southern California rival Simon Lamar, but Brinegar had other ideas.

“Michael just took off like a bullet and never slowed down,” Schubert said. “He did not follow my race strategy, and I’m glad he didn’t.”

Schubert explained that Brinegar should excel in the mid-distance events as he gets older and that he also has a strong IM, even if breaststroke remains a weakness. He expects that the 400 IM could be Brinegar’s third event beginning next year when he joins the Indiana Hoosiers program.

But Brinegar’s bread-and-butter race is still the mile, and he has also had some success in open water racing. Standout distance swimmers developing at Mission Viejo are far from unfamiliar, and Brinegar has had the unique opportunity to become acquainted with one of the best: 1976 Olympic gold medalist Brian Goodell.

After Brinegar’s record-breaking 1650 at Junior Nationals, Schubert immediately sent a text to Goodell.

Brian Goodell swimming in 1983 — Photo Courtesy: Tim Morse

“I kind of brag on Michael from time to time with Brian,” Schubert said. “I tell Brian that Michael is approaching his times, and Brian is very excited about that. When Michael moved to Mission Viejo, he had a chance to meet Brian a few times.”

Mission Viejo is one of the country’s successful clubs historically, and Goodell only accounts for two of the 20 Olympic medals Mission Viejo swimmers have earned and five of the club’s 22 world records. That history is not lost on Brinegar.

“It gives me a little more motivation when I come to swim in meets,” Brinegar said. “I know that I’m swimming for a club that has a great tradition. Every time I go and swim for Mission, I try to continue that tradition and do the best I can.”

Speaking of following in the footsteps of greatness, Brinegar aims for a target his mother met in 1976: the Olympics. In Montreal, Jennifer was a finalist in the 200 free and swam on the prelims of the U.S. women’s 400 free relay, which went on to win gold in the final.

But there’s no pressure to match what his mother achieved, Brinegar insists.

“It’s just great that she’s had that swimming experience, and she can help me whenever I have questions to ask her or if I need help with anything with swimming. I don’t look at it as, ‘I need to do this so I can do what she did,’” Brinegar said. “She doesn’t put that pressure on me that I have to do that. She just wants me to do the best I can.”

Brinegar has big targets for 2018, including getting down to the vaunted 15:00-barrier in the 1500 free long course. Even after a terrific 2017, he refuses to think of himself as having arrived nationally. Not yet, anyway.

“I still don’t think I’m at that point yet,” Brinegar said. “It feels good to being at that point where I can compete with some of the milers nationally.”

A great coach can help a potentially great swimmer achieve greatness.

Correction. 1976 was more than 40 years ago.

Bryan Erdmann