Record-Breakers: The Stars of the Abbreviated High School Swimming Season

The 2020 High School Swimming Record-Breakers (from August’s Swimming World Magazine)

Despite an abbreviated season that ended in March instead of May due to the COVID-19 pandemic, nine high school swimmers from eight different states combined for 11 public or independent school records and eight overall national high school records—including three times in one event!

**********

Since 1997, Swimming World has annually awarded High School Swimmer of the Year honors to the teenagers for superior efforts while representing their schools, but for 2020, there cannot be one such honoree. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, high school swimmers in certain states never got to have a season at all, and while all fall seasons and most winter seasons were completed, some state championship meets were canceled last minute or even stopped in the middle of the meet.

With that in mind, we recognize all the swimmers who broke national high school records this season and, specifically, the five swimmers who finished the season as new overall high school record holders: Claire Curzan, Gretchen Walsh, Phoebe Bacon, Kaitlyn Dobler and Matt Brownstead.

The Weekend of Records (February 7-8)

While the fall high school swimming season came without any overall national records, a whopping six went down during one early February weekend in North Carolina, Tennessee and in the Washington, D.C. area.

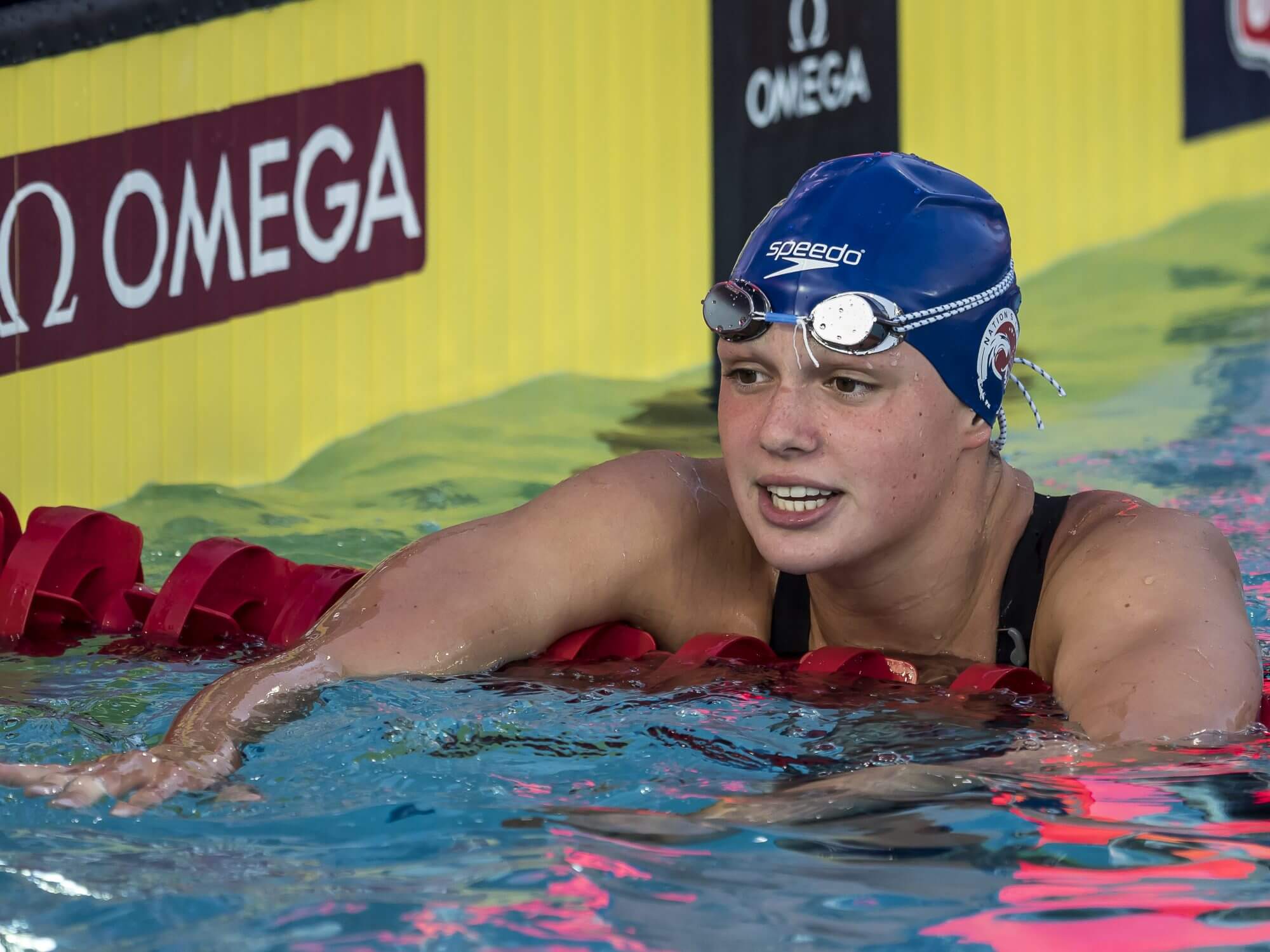

First came Claire Curzan, who broke the national high school record in the girls’ 100 yard butterfly at the North Carolina 4A Championships on Friday, Feb. 7. Representing Cardinal Gibbons High School (Raleigh, N.C.), Curzan, only a sophomore, swam a time of 50.35, smashing the 51.29 that Torri Huske had set one year earlier (2-15-19). Curzan also broke her own 15-16 national age group record and became the event’s 11th-fastest performer in history.

Claire Curzan — Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

Curzan considers high school swimming among the most fun experiences she gets in the sport. “The atmosphere is so exciting because for some people, it’s their first time making the statement, and for some people, they’ve been to meets beyond the state meet, but everyone is just kind of meshed together,” she said. “In the stands, everyone is just going crazy.”

The best part? A pair of shoes that her coach wears to the most significant meets of the season, a $20 value off Amazon that light up green.

After her 100 fly, Curzan’s big day became even better when she also took down the national record in the 100 back, swimming a time of 51.38 to beat Olivia Smoliga’s previous mark of 51.43 (11-17-12). But while that record lasted a little more than seven years, Curzan’s would last less than 24 hours!

* * *

That’s because the Tennessee Championships were taking place the same weekend in Knoxville, just a few hours’ drive west of Curzan’s meet in Cary, N.C., and the Walsh sisters were putting on a show for Harpeth Hall School (Nashville, Tenn.).

Gretchen Walsh — Photo Courtesy: Harpeth Hall Athletics Instagram (@hhathletics)

Junior Gretchen Walsh struck first on Feb. 7: She split 21.20 to anchor the opening 200 medley relay before she broke Abbey Weitzeil’s national record of 21.64 (5-16-15) in the 50 free with a 21.59. On Saturday, Feb. 8, Walsh broke another Weitzeil record (47.09r, 5-16-15) with a 46.98 in the 100 free. Like Curzan, Walsh made an impact on the all-time record books, and she ranks among the top 20 ever in both events.

“I was amazed. I didn’t think I was going to go that time. It was the fastest I’ve ever gone, obviously. It just felt really good, hard work paying off. Having my coaches there and my whole high school team there to congratulate me was just such a great experience. Obviously, I had a really great meet, and I was super happy,” Walsh said.

“I actually had just met Abbey Weitzeil for the first time on my Cal recruiting trip that year, and she’s an amazing person. Her success is really inspiring. Obviously, when I broke a record, I was really proud of myself, but breaking records, especially recent ones, from girls that are making the Olympics, that makes me really confident and feel that I have just as good of a chance to make it as they did.”

Two events after Gretchen’s sizzling 100 free, her older sister, Alex Walsh, came out for the 100 back and swam a 51.35, eclipsing Curzan’s record from the day before.

* * *

But that, too, would be short-lived, as Stone Ridge’s (Bethesda, Md.) Phoebe Bacon was getting ready to swim the event at the Metro (D.C.) Championships in Maryland. Bacon would blow right through the 51-second barrier and swim a time of 50.89.

Bacon has swum at the highest-level meets in the United States and also at the Pan American Games, but she calls Metros “by far my favorite” meet, and that included “possibly even Olympic Trials.” Inside a small, but raucous 25-yard pool at the Germantown Indoor Swim Center, Bacon actually swam just off her best time, a 50.70 from two months earlier that ranks her No. 25 all-time in the event.

Phoebe Bacon — Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

Unlike all but a few high school swimmers, Bacon has already come close to the apex of the sport. In 2018, she finished a surprising fourth in the long course 100 back at U.S. Nationals, behind Olympians Kathleen Baker and Olivia Smoliga and fellow teenager Regan Smith, now the world record-holder. In 2019, Bacon won gold in the 100 back and 400 medley relay at the Pan American Games, and in December, she edged out Smith to win the 100 back at the U.S. Open, her time of 58.63 making her the 12th fastest performer in history and the fourth fastest American behind Smith and Baker, the current and most recent world record holders, and 2012 Olympic gold medalist Missy Franklin.

And still, she was not too accomplished for her last high school race to have special meaning. So even though the race was just another race—a 100 back like she has done hundreds of times before—the circumstances made this moment particularly special.

Bacon remembers seeing three of her closest friends, all at the meet representing different schools, moved to tears watching her dominant and record-breaking 100 back, and she remembers having some of her Stone Ridge teachers in attendance watching. Swimmers from other schools approached her on deck and in the warm-down pool offering their congratulations.

“It almost brought me to tears at the end of the race. Three close friends of mine, I’ve grown up swimming with them literally since I was five years old, Maya Fischer, Anne Morris and Frank Schweitzer—I’ve grown up with them, love them to death. All three of them come up to me, and they all give me a big hug. Anne and Maya are almost in tears. Even Frank is, too. They’re just all so happy for me. That was the moment where I was just like, ‘Wow, this swim, I’m making an impact on other people through my swimming,’” Bacon said.

“I saw a few other of my friends, and they’re just like, ‘Oh my God, Phoebe. How did you do that? What on earth? That’s crazy.’ I was almost, like, speechless. I was like, ‘It’s a swim. I had fun. That’s all I did. I had fun.’”

Breaststroke Star in Oregon

Kaitlyn Dobler was 14 years old and hyper-focused on one goal, achieving her first Olympic Trials cut in the 100 meter breast, but she could not close the deal and drop the last few tenths she needed to earn a trip to Omaha.

“I went to so many meets and swam a lot of breaststroke and was just hyper-focused on trying to get that time, and it didn’t end up working out,” Dobler said. “I got close, but the closer I got to the meet, the more I was adding time. I feel like that was a point in my life where the pressure was still really getting to me.”

Not long after Trials, with the pressure greatly reduced, Dobler did swim faster than the cut, but it was too late to matter. Dobler calls that situation one of the most challenging of her swimming career, but her 2016 experience helped her develop a thirst for big moments, for high-pressure situations and challenges that swimming presents. And then, her swimming took off.

“I realized that I just needed to enjoy it, and that’s when I started really actually going faster and being more confident in my abilities for swimming,” Dobler said. “That helps me have less of a doubt whether or not I could do things like break records.”

Prior to 2018, Dobler had a lifetime best of 1:10.85 in the long course 100 breast, but she dropped almost two seconds that year and swam a 1:08.90 to capture an unexpected win at junior nationals. In 2019, she dropped another two seconds to a 1:06.97 that would rank her 18th all-time among Americans, and she finished second at both U.S. Nationals, then the FINA World Junior Championships in Budapest.

But as for her favorite moment in swimming, Dobler, who swims for Aloha High School (Beaverton, Ore.), named this year’s Oregon 6A State Championships on Feb. 22, when she won the 100 yard breast and set an overall national high school record. Her time of 58.35 cut 5-hundredths off Emily Weiss’ two-year-old national high school record of 58.40 (2-10-18).

Kaitlyn Dobler after breaking a national high school record

Unlike at the national and international meets in which Dobler had excelled, at her high school state meet, she was surrounded by swimmers she frequently raced as well as her parents and high school teammates. Instead of sharing a moment with maybe one or two people involved in her typical life at home, she had many in close proximity.

“My high school coach actually ran and hugged me while I was still in the pool, and then the announcer, who announces a bunch of meets in Oregon swimming, he said this was only the second (national high school) record broken in Oregon—(the other national high school record holder was Kim Peyton in 1974 and 1975)—and people in the stands started clapping,” Dobler said. “It was a really great moment, and it’s definitely something I’m going to remember for a really long time.”

Sprinting Past a Legend

Matt Brownstead of State College Area High School (State College, Pa.) spent the entire high school season geared toward 19 seconds of down-and-back speed and power. The target was the 50 free national high school record of 19.29 (11-9-13), and it belonged to one Caeleb Dressel, now widely considered the best all-around swimmer in the world.

“The 50 free has always been my best event,” Brownstead said. “I work really hard for stuff that goes into 50 free, underwaters and starts and whatnot, stuff like that. I’d been thinking about that the whole season, working toward that goal. Getting to States, I was confident in my abilities, but there’s always that little bit of nervousness that makes me wonder, ‘Oh, can I really do it?’”

Brownstead, headed to the University of Virginia this fall to swim under renowned sprint coach Todd DeSorbo, said that high school swimming was especially important for him, and he mentioned that he trained with his high school team during that season all four years. He also explained that his hometown of State College, Pa., has two major club teams, and swimmers from both come together on the high school team, a group of 40 whose camaraderie “is something that I always look forward to.”

Brownstead had won the 50 free the year before in 19.55, a state record, and in 2020, he annihilated the rest of the heat by more than a second. He touched in 19.24 and promptly slammed the water in excitement, having taken down the Dressel record by 5-hundredths.

“Even to be mentioned in the same sentence as him, it’s crazy, and it’s such a good feeling,” Brownstead said. “He’s out of this world. He’s incredible. Even like, ‘Oh, you just broke Caeleb Dressel’s record,’ it’s crazy. There’s nothing like it. It’s such a great feeling.”

Matt Brownstead celebrates breaking a national high school record

A few minutes later, Brownstead would anchor State College’s 200 free relay, swimming on a team with his younger brother, John. Having split 19.03 on a 200 medley relay earlier, Brownstead targeted getting under 19 seconds, and he ended up with an astounding 18.67.

“Just being there with those guys that we practiced with the whole year and I’ve gotten to know super well, really good friends, getting to swim with them, anchoring that relay, I think it was crucial to the fact that I went 18.6,” Brownstead said. “I wouldn’t have been able to do that with anyone else at that point.”

All that happened on the evening of Wednesday, March 11. In the hours after that, the entire country was upended as the string of COVID-19 closures began. Brownstead would return to the pool the next morning for the 100 free prelims, and he took the top seed in a quick 43.29. He returned to his hotel for a nap with his sights set on breaking into the 42-second range in finals, but that swim never happened.

“Before prelims even started, I was talking to my coach. I was like, ‘There’s no way they cancel finals, right?’ She was like, ‘Nah, don’t worry about that,’” Brownstead said. “It was like noon or maybe 1 p.m. when our coach came to our room and told us finals were canceled. She was pretty emotional. I was napping when she came to my room, so I was groggy when I woke up. I was kind of like, ‘Wow, this is crazy.’ Five minutes later, we were packing our stuff and getting ready to leave. It was definitely not the end that I expected to the season.”

Brownstead said he was not devastated about the abrupt end to the meet, but he did get one opportunity for closure on his high school swimming career. As his team returned home that afternoon, their coach got clearance for him and the team’s other finalist, Foster Heasley, to swim their races in their pool at school. Brownstead remembers swimming his 100 free about a second slower than he did in prelims, but at that point, it didn’t really matter.

“We got to swim there, broke some pool records. That was really cool. It was kind of a consolation for what we missed. They had a bunch of parents and kids come out and cheer for us and stuff like that,” Brownstead said. “It was kind of cool to swim that with everyone watching and cheering and swim with my best friend in the other lane.”

* * *

Three other swimmers broke national high school public or independent school records in 2020. Pennington School’s (Pennington, N.J.) David Curtiss set an independent school record in the 50 free, with his 19.42 beating the previous record of 19.54r (11-10-12) held by Ryan Murphy. Yorktown’s (Arlington, Va.) Torri Huske, who lost her 100 fly overall record to Curzan, swam a 50.69 two weeks later to eclipse her former record (51.29, 2-15-19) and set a new public school mark. And Carmel’s (Carmel, Ind.) Jake Mitchell swam a 4:14.68 to take down the national public school record in the 500 free, beating Jake Magahey’s 4:15.63 (2-9-19).

Each of the nine swimmers who broke a high school record in 2020 have successes well beyond high school swimming, and all of them represented the United States internationally in 2019. Seven of them swam at the FINA World Junior Championships, and six took home medals from that meet. In fact, the foursome of Curzan, Dobler, Huske and Gretchen Walsh combined to win gold in the 400 medley relay.

Meanwhile, Bacon and Alex Walsh swam on the senior level at the Pan American Games in Lima, Peru, and each won two gold medals: Bacon in the 100 back and 400 medley relay, and Walsh in the 200 back and 200 IM.

Each of the high schoolers spoke glowingly about their international experiences, including exciting moments of team camaraderie and podium honors and relay records at the World Junior Championships and the sage advice that Bacon and Alex Walsh received from experienced veterans at the Pan Am Games. Still, each of them had a special place in their hearts for high school swimming, an experience that swimmers of wide-ranging ability levels can appreciate together. Even for these budding stars, excelling on the high school level remained special.