European Tournaments Offer Testing Ground for Proposed FINA Water Polo Rule Changes

By Michael Randazzo, Swimming World Contributor

Tangible outcomes of rule changes proposed at the FINA Water Polo Conference held last May in Hungary are now on display back where the changes were proposed. The 4th FINA World Men’s Youth Water Polo Championships 2018, being held August 11-19 in Szombathely, Hungary, is the first of three proposed testing opportunities to determine the viability of select changes.

Photo Courtesy: FINA

Consisting of 20 teams from all continents, FINA Youth Worlds includes eight teams from Europe, five from the Americas, three from Asia, two from Oceania and two from Africa.

This is an ideal starting point for FINA’s attempt to transform a sport which many believe is not spectator friendly enough to thrive in the new century. In fact, the conference in Budapest was keen to point out the many flaws—from indifferent marketing to indecipherable rules—plaguing the oldest Olympic team sport.

Some, including Ratko Rudic, Ricardo Azevedo and Adam Krikorian, are less concerned with rule changes than with providing more visibility for water polo, which has expereinced a popularity dip in Europe.

“Before we do anything, before we start trying to change all these things, let’s find out how good our sport is,” Krikorian said in an interview last May. “It’s impossible to know where your holes are when you’re not operating at close to 100 percent. We have an opportunity—70 percent we’re not maximizing. We get caught up in: We need to change 20 different rules.”

Is change quantifiable?

The most important change on trial is Rules Amendment #8 which impacts Rule WP 14.03. The existing rule has to do with a shot outside of 6 meters after an ordinary foul. In the past the attacker who was fouled could not fake; now—according to notes from FINA’s Technical Water Polo Committee (TWPC)—after the player visibly puts the ball in play, that player can fake and shoot or swim and shoot.

An endangered play? Photo Courtesy: AWFoto.nlGertjan Kooij

The other half of the proposed rule is: “Once the player visibly puts the ball into play, the defender can attack the player with the ball,” said the TWPC’s notes about the change. A defender can now react to a prospective shot, rather than giving the attacker an uncontested scoring opportunity.

Another key adjustment has to do with an attacker on a break. The trailing defender can no longer pull the player from behind without incurring a foul. In the old interpretation, the attacker needed to drop the ball to draw the exclusion, but the TWPC was clear that leaving this up to a referee’s interpretation was a mistake.

“If the defender contacts the arm, back or shoulder, a penalty must be awarded.” the TWPC wrote. “This will eliminate the potential decision and call of the referee that the ‘ball was in the hand’ that we saw in the past and which was incorrect in many cases.”

Rule Amendment #2 revises where free throws are taken; proposed is changing the location of the ball after a foul. Before—according to Rule AP 19.1, a free throw was taken where the foul was committed, pulling the ball back from an offensive opportunity. Now the free throw is taken from where the ball has travelled since the foul was committed—an important distinction in a fast-paced game.

Changing Rule WP 20.15 initially appears cosmetic—but it could have significant impact if approved. It cuts the time for an attacking team’s second or subsequent possession to 20 seconds no matter what the circumstances. According the TWPC: “The team is not to lose time as a result of the exclusion, nor is the offending team to benefit from a reduction in possession time.”

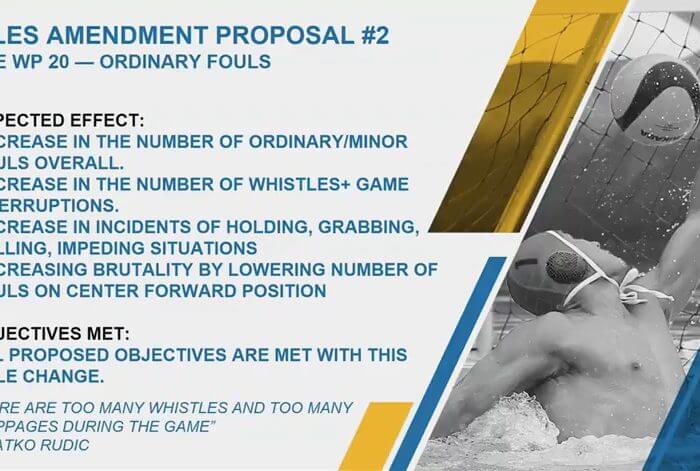

Too many whistles?! Photo Courtesy: FINA

This means that 10 seconds will be shaved off of the possession no matter if it’s a goalie save deflected out of play, a rebound picked up by the attacking team or an exclusion called during an offensive possession. This time reduction is also in effect for corner throws; those are now 20 seconds, rather than 30.

Not everything is changing

Some rule changes will not be tested at this tournament, including a decrease in halftime from five to three minutes, and the maximum number of players set at 13 (plus 2 substitutes). There’s no surprise here; a more informative testing opportunity comes next month at FINA’s Men’s Water Polo World Cup 2018 in Berlin, when the national teams of Australia, Croatia, Hungary, Japan, Serbia, South Africa, the U.S and host Germany will play under the new rules.

This trial period—including one additional opportunity later this month, at the FINA World Women’s Youth Water Polo Championships in Belgrade—will allow analysis before the Olympic qualification cycle, which begins next spring. Changes prior to the 2020 Olympics, including a reduced roster of 11 players for all men’s and women’s squads, and an increase of women’s teams from eight to 10, were already approved more than a year ago, generating much disagreement.

Krikorian is right; before making changes, clearly identify what’s working. But trying new things—especially if it makes the polo easier to understand—is also valuable.