Refocused Paul Le Pushing Toward Vietnam Olympic Dream

Refocused Paul Le Pushing Toward Vietnam Olympic Dream

The dream was, in Paul Le’s words, starting to feel “hopeless.”

Le was 26, still training at his alma mater, Missouri State, mired in the doldrums of an Olympic cycle in 2018, the Tokyo Games he aimed for still more than 18 months away. He’d seen many of his swimming peers trade the pool for a working career, while the logistics supply and chain management major kept hammering away in the pool.

Paul Le, second from left, and members of the Missouri State coaching staff at the 2013 NCAA Championships; Photo Courtesy: Missouri State Athletics

The goal for Le, born in Oklahoma to parents that escaped Vietnam in the mass migration of the late 1970s, was to represent his family’s country on the Olympic stage. He’d come close in 2016, left off the team at the last moment, and planned to spend the next Olympic cycle working to rectify that exclusion. It has meant repeated trips to Vietnam for competitions, three straight long-course World Championships and a noteworthy haul of medals at the Southeast Asian Games.

At home, Le made the switch to Wolfpack Elite in the spring of 2019, after seven years in Springfield and coach Dave Collins. The change of scenery was in service of an Olympic A-cut chase, assuring that nothing can keep him home from the Tokyo Games.

But the larger goal, as it has been since a chance encounter at a Pro Swim Series stop in 2015, remained unchanged.

“I’ve been going to Vietnam ever since I was a kid, and it kind of sparked with me that maybe if I wanted to continue swimming after my undergrad, why not represent a country that, I’m not from there but I would always go there quite a few times since I was a kid?,” Le said recently. “Why not try to do that?”

A mid-major ‘star’

From the moment Missouri State coach Collins got Paul Le on campus, he knew he’d unearthed a gem.

Collins has successfully panned for gold in Oklahoma before, and Le fit the bill as the next nugget extracted. (Le attended high school in the same district as Olympian David Plummer.) His talent was raw but obvious, a three-time state champ. By being, in Collins’ measure, under-coached in high school, the coach knew there was room to grow.

“You could just tell when you watched him swim that he had incredible feel for the water, and he could kind of swim all the strokes but hadn’t quite put it together yet for an IM,” Collins said. “But you could tell he was talented.”

Le made an instant impact for the Bears. He earned a pair of bronze medals at the Mid-American Conference Championships as a freshman and earned three NCAA B cuts. It built to an impressive appearance at the 2012 U.S. Olympic Trials, where he finished 38th in the 100 backstroke and 58th in the 200 back.

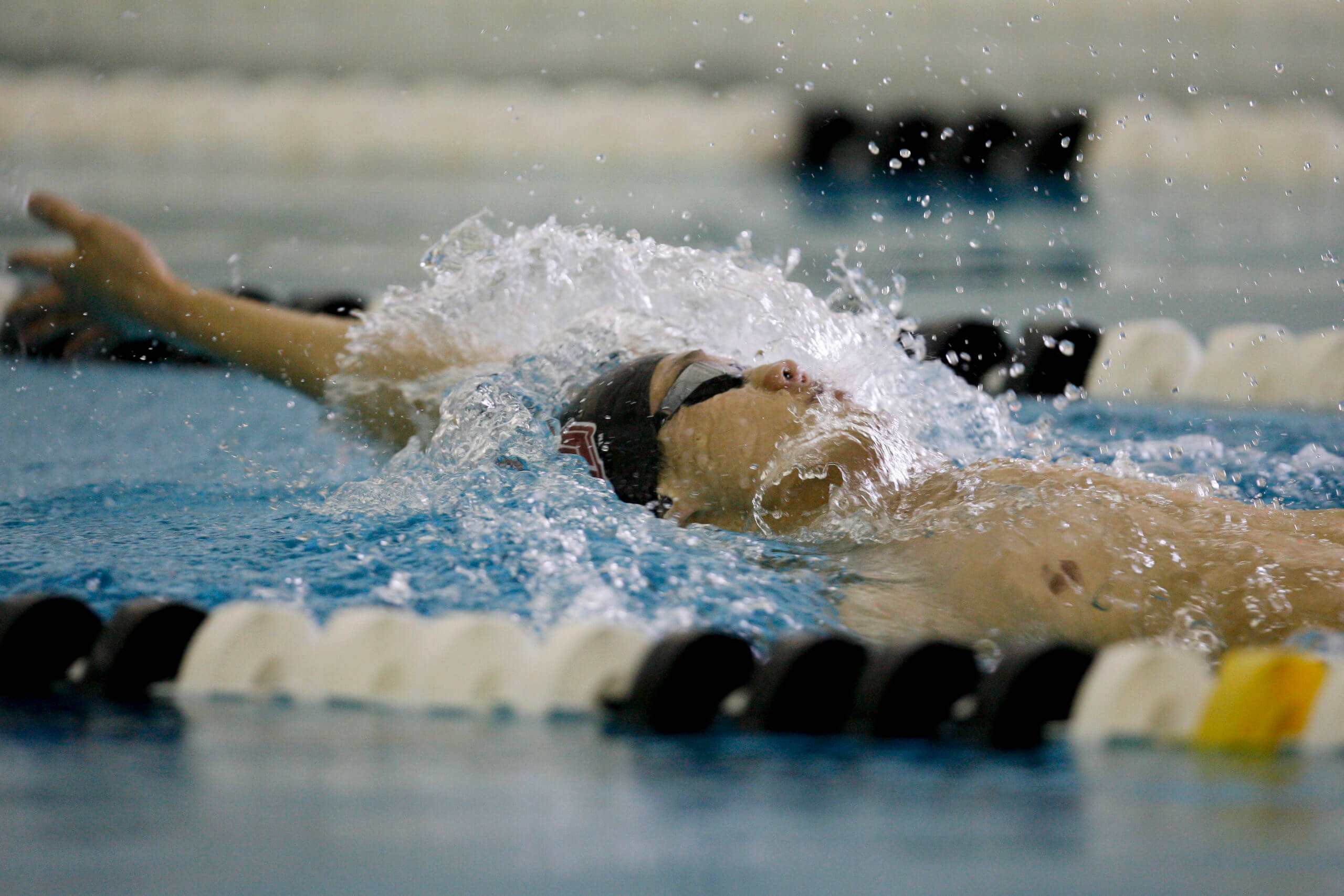

Paul Le while at Missouri State; Photo Courtesy: Jesse Scheve/Missouri State Athletics

As a sophomore in 2013, Le became just the sixth Missouri State swimmer and first since 2005 to qualify for the NCAA Championships, getting there in three events. He even earned a second swim in the 200 back, taking 15th place. That berth occasioned a ride up to Indianapolis with as many people as Collins could stuff into a van in what he hoped would be a program turning point.

“We walked in that final day pretty proud,” Collins said. “That was a neat moment for our program as a whole, for us as coaches and for him as an athlete, to put Missouri State at that level. It was our first qualifier for us as a staff. … He really put us on the map nationally.”

What once was an oddity became the norm with Le. Since his first NCAAs swim in 2013, Missouri State has sent 11 swimmers to the last six editions, including three straight years in which Le qualified for the maximum of three individual events. He finished 20th in both the 200 individual medley and 200 back as a junior and graduated in 2015 with three school records, two of which still hold.

All that could’ve made for a tidy, mid-major career had it ended at graduation. That was the plan, until a chance meeting at a Pro Swim Series event in 2015 in Mesa, Arizona, when Le met Vietnamese coach Dang Ahn Tuan. Then the coach of women’s star Vien Nguyen, Tuan approached Le to see if he had interest in representing Vietnam. Le had pondered the possibility but was unsure how to go about it. With Tuan’s help, Le was able to fast-track the process, gaining citizenship that year.

Though not the biggest program, Collins and Missouri State had what Le needed to pursue that dream. It’s been a frequent outpost for foreign internationals, having tutored Olympians from countries like Guatemala, Bulgaria and Zambia. The latest, Latvian Uvis Kalnins, competed at the 2012 and 2016 Games.

Le, who competes internationally with the added family name of Paul Le Nguyen, was ready to do what it took to be the latest in that list.

“When we are in the recruiting phase, we always talk about trying to maximize everybody’s potential and their goals, and when we were recruiting Paul, the Olympic Games was not part of the conversation,” Collins said. “I think what it does say is as athletes can evolve through our program – we never recruit people and say, ‘we’re going to get you to the Olympics.’ But with someone like Paul, I think it shows that if you go to a program and you work hard and it’s the right fit, then great things can happen.”

The road back home

Muoi Le and Tammy Davis met in Oklahoma in the 1980s, traveling parallel, equally harrowing journeys there. Both were Vietnamese boat people, who emigrated shortly after the country’s reunification under the Communist banner in 1975. More than a million people fled the nation, an exit the government had declared illegal, to seek greater freedoms or escape persecution, many taking to open water in vessels of varying degrees of seaworthiness, hoping for a fate better than the one they left. For the 800,000 that made it safely, another estimated quarter of a million died in the passage.

Davis was hours away from being in the latter category. She was 17 when she left her hometown of Qui Nho’n, on the coast nearer the demilitarized zone that separated the country from 1954-75 than to the South Vietnamese capital of Ho Chi Minh City. For three days and two nights, she drifted on a packed boat that had run out of fuel in open water. Forty years later, Davis is unsure how much longer her boat could’ve survived the choppy seas.

“It was scary, scary,” she said. “I’m really lucky and thankful to the Lord that I still am alive. It was three days, two nights, in the middle of nowhere. … If I waited another day, I would’ve died in the sea. There was no way I would’ve survived.”

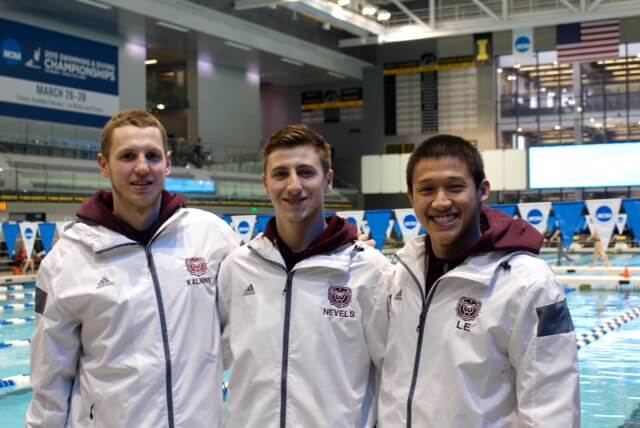

Paul Le, right, with Missouri State teammates Uvis Kalnins, left, and Garrett Nevels at the 2015 NCAA Championships; Photo Courtesy: Photo Courtesy: Missouri State Athletics

Eventually, they crossed the path of an English ship, which took the passengers aboard, bound for a refugee camp in South Korea.

The particulars of Moui Le’s journey differed, but the peril was the same. He grew up in Mui Ne, a village on the coast 200 kilometers from the capital, where he and his eight brothers worked as fishermen. With strict rationing of fuel, they squirreled away what they could each day for months, buried under the sand to evade military patrols. When Moui Le and a friend finally set sail, they were rescued and sent to a resettlement camp in Malaysia.

With church sponsorship, both Moui Le and Tammy settled in the United States. Paul and two sisters, who all grew up in a thriving community of ex-pats in Moore, Oklahoma, would follow. They maintained connections to their parents’ home country through relatives and friends. Though Moui Le has never returned to his homeland, Tammy has, and Paul has stayed with extended family on trips back.

It’s a more fraught relationship than most have with their heritage. Tammy appreciates the home she’s made in the U.S. and the opportunities it’s afforded; she mentions several times the pride in Paul receiving his degree, the chance at an education something she specifically fled for. But she has no qualms about seeing her son represent Vietnam.

“It’s great,” she said. “I’m so proud of him swimming for Vietnam, because the United States is so hard to swim for. I’m really proud and he works so hard.”

Paul’s feelings are unconflicted, too. His connection has never been to the government that his parents fled. From a young age, his idea of Vietnam was in the glimpses of trips back home and in the culture that surrounded him, in Oklahoma and back in Asia.

“Ever since I was a kid, I’ve always wanted to one day retire and live there,” Paul said. “My mom’s and dad’s brothers and sisters are still in Vietnam, so I always go back and visit them. Every time I go back to Vietnam after a meet, I want to stay there an extra meet after the racing is over. I love it there.”

From Rio, with renewed hope

Paul Le’s plane ticket was set, his Olympic paperwork submitted, in the spring of 2016 when he found out he wouldn’t be going to Rio.

Le thought he’d done enough to get on the coaches’ radars to earn the Olympic trip. But that didn’t turn out to be the case. Instead of the capstone to his career, it became one more chance to reevaluate what he wanted from the sport. Even with four years ahead of him, Le approached a new cycle with few reservations.

“It was a heartbreak. … But I think it renewed my passion for swimming just because I didn’t have any pressure,” he said. “… I kind of wanted to prove people wrong. I wanted to prove that I was capable of qualifying.”

Le debuted for Vietnam at the 2015 World Championships, swimming all three backstroke events. He placed in the top 35 of both events at Worlds in Budapest in 2017 and went as high as 29th in the 100 back at the 2018 short-course Worlds.

Paul Le, center, at a Pro Swim Series event; Photo Courtesy: Missouri State Athletics

The Southeast Asian Games, though, is where he really shined, the 11-nation regional event providing a more attainable target for medals for the Vietnamese program. He came through in 2017, winning bronze medals in four events – the 50 free, 50 back, 50 fly and 200 IM, the former a national record. The effort was hailed by the general secretary of the Vietnam Aquatic Sports Association as a game-changer in its international recruitment efforts.

In 2019, he upgraded to silver in the 100 back, again in a national record of 54.98. (It’s his closest margin to a coveted A cut, which sits at 53.85.) He added three bronzes, including the 4×100 free relay. The 2021 SEA Games will take place in Hanoi, which Le, who will then be 29, has eyed as a possible full-circle capper to his career.

In all, he holds national records in four individual events across three strokes. He’s made twice-national pilgrimages to Vietnam, for provincial championships in the Mekong Delta region and for nationals, long- and short-course.

It should be enough, with how Olympic universality spots are doled out, to earn Le his Olympic moment. (As of the end of 2020, one Vietnamese swimmer, Nguyen Huy Hoang in the men’s 800 and 1,500 free, had guaranteed a spot for Tokyo.) But after the disappointment of 2016, Le wants to dispel any doubt. Hence the change from Missouri State, where long-course training was confined to the summer months, to full-time long-course tutelage at Wolfpack Elite. Le isn’t alone there, among a number of postgrads who’ve flocked to Braden Holloway’s program.

Collins saw Le take time to adjust to life as a pro, from the team-first mentality of college swimming in which he excelled to the job being all about him. Le, who was studying for his Master’s degree at Missouri State, has gone from being a big fish in a small pond to a much, much larger pond, learning to hold his own (such is the speed at Wolfpack that it’s a challenge keeping up with some of the women’s sprinters, Le said). But that departure from his comfort zone is precisely why he sought the change.

“Here, they’re like, dude, keep going,” Le said. “The coaches here really encourage you and make you feel so much better about yourself. They’re always in your corner and that’s probably where I had that thought, just chasing a hopeless dream. Every kid wants to go to the Olympics, but then if you went to a small, mid-major college, it’s like what are you doing? But here, there’s that perspective to keep chasing that dream.”

Le has made the extra time to the postponed Tokyo Games work for him. He needed time off after the 2019 SEA Games, held in December in the Philippines, to rest an arm injury. He’s coming off a rare chance to compete in the Janis Hope Dowd Invitational at the University of North Carolina (short-course yards) in December, where he went 1:45.56 in the 200 IM and 46.85 in the 100 back, the latter behind Wolfpack Elite teammate Coleman Stewart.

Part of the balance against burnout has been a side passion, shared with his partner, Josie Pearson, a 2019 Missouri State grad (and a two-time Missouri Valley Conference gold medalist and four-time all-conference pick in her own right). Their Instagram account, @two_escapers, chronicles their adventures with two rescue dogs and their Jeep Cherokee, adventuring through all manner of outdoor, hiking and camping life.

Though it’s not always conducive to a scheduled practice time six days a week, Le uses it as a counterbalance for that seventh day, something that keeps his mind focused on the task at hand. It’s a little easier with a fellow swimmer who can understand some of the pressures at play.

“Right when Saturday practice ends, I know I need a mental break from the pool,” Le said. “So that’s where adventuring on the side comes in. I need a break from the pool. I’m hanging out with the same people, my teammates, five hours a day, so when the week is over, we’re a little sick of each other. … So it’s nice to understand what an athlete goes through, and she also understands the mental break aspect of it.”

It’s all in service of Le’s larger dream, something that would mean the world to him and his family.

“That would be super,” Davis said of Paul making the Olympics. “It would be wonderful and we’re proud of him, and I’m looking for to it. He works so hard.”

Paul is an awesome swimmer and better yet an awesome person. He and Josie push each other to be the best they can be at everything they do.

Paul is an inspiration to all of us!! Good luck!!