Passages: Aleksandr Kabanov, Russian Olympian as Player and Coach, 72

Aleksandr Kabanov, who struck Olympic gold in 1972 and 1980 as a player for the Soviet Union men’s water polo team and a pair of bronze medals as coach—in 1988 as an assistant with the USSR in the Seoul Olympics, then as head coach for Russia in the 2004 Athens Games—passed away Wednesday at the age of 72.

Kabanov, who was also a published author, with 1988’s The Ball on the Water, is one of few Olympians to have collected medals as both a player and coach.

A 2001 inductee to the International Swimming Hall of Fame, Kabanov was the head coach for the Russian men’s team in 1996 when they returned to Olympic competition following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991. He again led the Russian men in 2004, and was head coach for Russia’s women’s team that finished fifth at the 2012 Games in London.

Kabanov coaching in 2012. Photo Courtesy: Alexander Vilf

One of the most decorated polo players in his country’s history, Kabanov competed at the height of the Cold War between the Soviets and the Americans. Tensions reached their zenith in 1980 when U.S. President Jimmy Carter—citing the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—elected to boycott the Moscow Olympics. In all, 65 countries declined an invitation to the Soviet Union, sullying what was intended to be a moment of triumph for the USSR.

With the powerful Team USA absent, Kabanov and his teammates captured gold over a field that included Hungary, reigning Olympic champions, the formidable Yugoslavia—featuring a young Ratko Rudic—and Cuba, which had kept the Americans from the Montreal Olympics with a decisive win in the 1975 Pan American Games

In 1984 the Soviets returned the favor. They and their allied Eastern Bloc countries—including East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and others—boycotted the Los Angeles Games.

“I played for two years with Aleksandr Kabanov on the USSR national team,” said Sergey Naumov, who was a member of the Soviet squad for a decade before representing the Unified Team in the 1992 Barcelona Games. “In 1983, we won the World Cup in Los Angeles and a year later we were preparing for the Olympic Games in [the U.S.].

“Unfortunately, politics intervened and we did not go to the [1984] Olympics, although we would have become Olympic champions for sure because at that time the USSR team was very strong. This is a well-known fact. They called us The Big Red Car.”

It was not until 1988 in Seoul that the Cold War antagonists would again face each other in the sport’s premier showcase. The U.S. took an 8-7 decision in a taut semifinal that propelled the American to a finals match-up with Yugoslavia, a bitter 9-7 defeat that gave the erstwhile nation a second straight gold. The Soviets settled for bronze, winning a high-scoring affair against West Germany.

Naumov, now a FINA-certified referee and sports personality in Russia, said that, politics aside, in the pool it was all business: “Despite the difficult relations between our countries, we have always had good relations with American water polo players.”

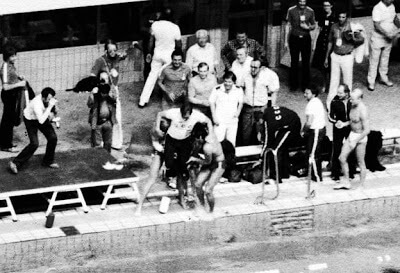

USSR celebrating 1980 Moscow win. Photo Courtesy: Waterpolo Legends

Kabanov had his first sweet smell of Olympic success as a 24-year-old at the Munich Games in 1972. The Soviets went unbeaten in the tourney, with seven wins and two draws, as Kabanov and teammates Aleksei Barkalov and Viacheslav Sobchenko—who also would ascend to the top podium in Moscow eight years later—propelled the USSR to its first-ever water polo gold.

According to Naumov, Kabanov was known as a versatile player who was strong on both defense and offense.

“I had a lot to learn as a young player,” the veteran of two Olympics (1988, 1992) said. “Like a chess player, he read the game several moves ahead. In every way, he was a great player.”

After his stint under USSR coach Boris Popov in the 1988 Olympics, Kabanov returned in 1992 as an assistant with the Unified Team, which consisted of athletes from twelve of the fifteen former Soviet republics. In 1996 he was head coach for the Russian entry, which finished fifth at the Atlanta Games.

In 2004, he once more led to the Russian men to the Olympics, where his team produced a bronze medal with a 6-5 win over host Greece, and again in 2012 when he coached the Russian women to a fifth-place finish in London.

According to Naumov, his ability to successfully work with players of both genders was noteworthy.

“Kabanov was not only a great player but also a great coach,” his former teammate said. “There is hardly any other specialist who has successfully worked in water polo with both men and women.

Like many connected with the underappreciated sport that for some becomes a life-long obsession, Kabanov was a polo devotee to the end.

Said Naumov, “He was madly in love with water polo and was devoted to this beautiful sport until the last minute.”