Olympic Throwback: The Dolphin Kick Controversy of Kosuke Kitajima vs. Brendan Hansen

The Dolphin Kick Controversy of Kosuke Kitajima vs. Brendan Hansen

The final of the 100 breaststroke at the 2004 Olympics in Athens was shrouded in controversy after Japan’s Kosuke Kitajima was shown performing an illegal dolphin kick on the way to defeating American Brendan Hansen. The move by Kitajima set off a charge of cheating by Hansen’s teammate and friend, Aaron Peirsol, and also proved to be the impetus for a rule change in the stroke.

Certain athletes will be forever linked. While many boast stand-alone credentials of great prestige, some possess a bond with another which is inescapable. On the basketball court, only first names were needed: Larry and Magic. In the ring, it was Ali vs. Frazier. On the grass of Wimbledon, it was Borg vs. McEnroe.

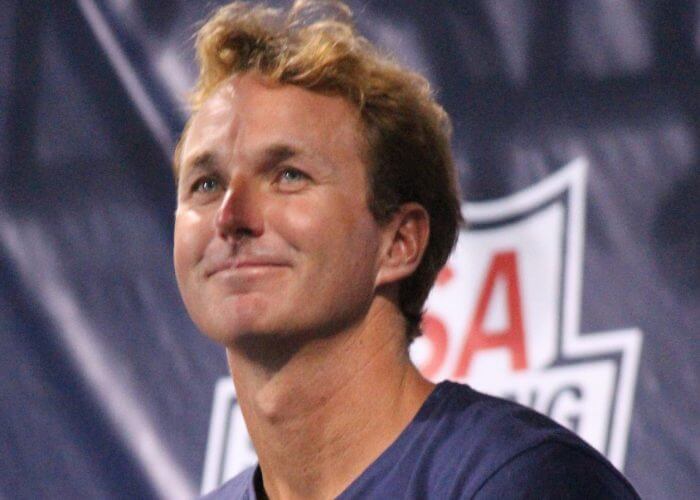

Swimming, too, has had its share of high-profile rivalries, duels spanning all of the strokes. In the breaststroke discipline, there has been nothing close to matching the rivalry of the United States’ Brendan Hansen and Japan’s Kosuke Kitajima. For a little more than a decade, the men pushed one another – and their events – to greater heights. A coolness primarily permeated the relationship, a language barrier not helping matters, although warmth was found when their dueling was done.

Yet, for all the showdowns shared between Hansen and Kitajima – from Japan to Spain to Canada to Australia, and beyond – nothing compares to what unfolded in a little more than a minute at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. The events of August 15 defined – in part – a pair of careers and ultimately triggered a change to the breaststroke which continued to bring controversy.

Photo Courtesy: Peter H.Bick

The early years of the Hansen-Kitajima rivalry resembled a tennis match, the men volleying accomplishments and titles back and forth. Kitajima broke onto the Olympic stage first, qualifying to race the 100 breaststroke and 200 breaststroke at the 2000 Games in Sydney. Although Kitajima failed to advance beyond the preliminaries of the longer distance, he just missed a medal in the 100 breast, finishing fourth. As important, he gained valuable experience which proved beneficial in the years – and Olympiads – to come.

Hansen, on the other hand, experienced his first true heartache during the 2000 campaign. At the United States Olympic Trials in Indianapolis, an 18-year-old Hansen placed third in both the 100 breaststroke and 200 breaststroke. With only the top-two finishers in each event qualifying for the Olympic Games, Hansen found himself in the worst position possible. The 200 breaststroke was particularly agonizing, as Hansen was charging down the last lap and gaining ground on the leaders with every stroke. Had the race been 201 meters in length, he probably would have earned a trip to Sydney. Instead, he was 15 hundredths of a second short.

Several athletes in Hansen’s position have allowed that near-Olympic miss to mentally destroy them, to cast doubt over whether they could get over the hump and achieve a lifelong dream. Hansen, exhibiting maturity well beyond his teenage years, opted for a different approach. Although deeply disappointed, Hansen used the events in Indianapolis to drive him.

“There were a few days when I didn’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. It was hard,” he said. “But I’m going to use it as a positive. You can’t regret what happened in the past, but you can use it as motivation, for myself and my teammates. I’m a man on a mission.”

Off to the storied program at the University of Texas following the Olympic Trials, Hansen didn’t waste time grinding away under the watch of coach Eddie Reese. During his freshman year, he won the first of four NCAA titles each in the 100 breaststroke and 200 breaststroke, that momentum leading to the biggest moment of his career – to date – at the 2001 World Championships in Fukuoka, Japan. While not considered a favorite, Hansen captured the gold medal with a championship-record time of 2:10.69, Kitajima picking up the bronze medal a little more than a half-second back.

“His swimming at the (Olympic) Trials was a great indicator of his ability,” Reese said of Hansen. “But to get third in both events would floor most people. Not Brendan. He took no time to get back on his horse and get back to work.”

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

The battle between Hansen and Kitajima was clearly on. They each walked away with one individual title at the 2002 Pan Pacific Championships, but the end of that season and the 2003 campaign belonged to Kitajima. He set his first world record in the 200 breaststroke at the end of 2002, breaking the iconic 10-year-old standard of American Mike Barrowman. Then at the 2003 World Championships, Kitajima broke world records en route to gold medals in both the 100 breast and 200 breast, Hansen taking silver and bronze, respectively.

It didn’t take long, however, for the momentum to shift back in Hansen’s favor. At the 2004 United States Olympic Trials in Long Beach, California, Hansen popped – arguably – the two-biggest performances of the meet. He shaved 48 hundredths off Kitajima’s world record in the 100 breaststroke and sliced 38 hundredths off Kitajima’s global mark in the 200 breaststroke. The stage was set for an epic duel at the 2004 Games in Athens, the birthplace of the Olympics.

Neither Hansen nor Kitajima had any difficulty navigating the preliminaries and semifinals of the 100 breaststroke, although their times did not match what they previously produced. Still, as the men took to the blocks for the final of the 100 breast on August 15, Hansen’s birthday, the spectators at the outdoor venue expected a down-to-the-wire duel.

Indeed, a neck-and-neck showdown is what evolved. Stroke for stroke over two laps, Hansen and Kitajima battled. As they touched the wall and looked to the scoreboard, it was shown that Kitajima got to the touchpad first, his time of 1:00.08 narrowly edging the 1:00.25 of Hansen. At the realization of his triumph, Kitajima let out several primal screams, much to the dismay of Hansen. But the screaming was just starting.

Underwater cameras used for television purposes showed that Kitajima had twice violated a rule of the stroke. He was shown using a downward dolphin kick at the start of the race and again after the turn at the 50-meter mark. At the time, the event did not allow for any dolphin kicks, unlike the other strokes in the sport.

Hansen didn’t cry foul at the end of the race. For one, that wasn’t his style. More, he had no way of knowing what transpired in the lane next to him. Hansen was fixated on his race, and that is where he remained after it had concluded. Hansen saw the clock and knew he was nearly a second slower than the time he produced at the Olympic Trials. He blamed only himself for not claiming victory.

Photo Courtesy: Griffin Scott

While Hansen was mum on the sight of Kitajima dolphin-kicking on two occasions, his teammates were not prepared to stay quiet. Sprinter Jason Lezak voiced his displeasure over Kitajima’s tactics, but his words hardly resonated when juxtaposed with the statements of Aaron Peirsol, Hansen’s teammate at the University of Texas and friend. Peirsol, who swept the backstroke events at the Athens Games, went on the offensive almost immediately after the race.

“He knew what he was doing,” Peirsol said of Kitajima. “It’s cheating. Something needs to be done about that. It’s just ridiculous. You take a huge dolphin kick and that gives you extra momentum, but he knows that you can’t see what from underwater. He’s got a history of that. Pay attention to it.”

Experts in the sport, primarily coaches, figured the power of a dolphin kick was good for up to two-tenths of a second per lap, meaning Kitajima’s usage easily provided the winning difference over Hansen. But none of the deckside judges saw or were willing to call the violations and because video replay is not used in swimming, technology could not be employed. With no room to file a protest, Hansen was out of luck. He was also admirable in the way he handled the situation.

“It would be a big deal for an official to come out and to disqualify somebody,” Hansen said. “I can only account for my actions and I know exactly what I did in my race. Everything else, I hope the officials who are sitting right next to me will take care of that. They are not there to have a front-row seat and watch the Olympic Games. They’re there to take care of the rules. I believe that’s what they do.

“I don’t agree with (Peirol’s) actions because the U.S. is very diplomatic on these sorts if things. He was a little fired up and he was protecting his teammate, that’s all.”

Kitajima initially declined to address the topic after the race, although his coach, Norimasa Hirai, defended his pupil by indicating he has never performed an illegal kick. A day later, with the 200 breaststroke looming, Kitajima discussed the accusations levied by Peirsol and maintained his innocence.

“There’s nothing about the race I actually remember,” Kitajima said. “I got in and did the best I could. I just remember when I finished and I won, I was as happy as I’ve ever been. A lot of people will now start to pay attention more than before. When I heard the comments by Peirsol, I was really surprised because I always try to have fair competition. I’m always trying my best within the regulations. I have never, ever been cautioned by the official judges.”

Three days after claiming his controversial gold medal in the 100 breaststroke, Kitajima left no doubt about his dominance in the 200 breaststroke, winning by more than a second over Hungarian Daniel Gyurta, with Hansen taking the bronze medal. Hansen got his gold on the final night of action when he joined Peirsol, Ian Crocker and Lezak on the triumphant 400 medley relay.

The controversy sparked by the final of the 100 breaststroke in Athens did not dissipate and forced a rule change to the sport. Almost a year after Kitajima’s clouded win, FINA, the international governing body of swimming, decided to amend its regulations by allowing athletes a single dolphin kick off the start of each race and off each turn. Basically, rather than placing the onus on officials to enforce the rules, FINA took the easy way out.

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

In the meantime, Hansen regained the upper hand in the rivalry with Kitajima. Hansen won gold medals in the 100 and 200 breaststroke events at the 2005 World Championships in Montreal, then won both events at the 2006 Pan Pacific Championships, twice beating Kitajima and lowering the world record in the 200 distance. Before illness forced Hansen to withdrawal from the 200 breaststroke at the 2007 World Championships in Melbourne, he again beat Kitajima in the 100 breast.

The 2008 Olympics, though, proved to be forgettable for the American. Before the Beijing Games, Hanen failed to qualify for the 200 breast, leaving him with just the 100 breaststroke and medley relay on his schedule. Hansen’s inability to qualify in the 200 breast elicited a jab from Kitajima, who said: “For a swimmer of his level, it shouldn’t be that difficult to qualify. He didn’t seem to set his goals and rise to the challenge just one month before the Olympics.”

Kitajima went on to repeat his Olympic sweep of the breaststroke events in Beijing while Hansen finished out of the medals in the 100 breast, placing fourth. Although Hansen helped the U.S. prevail in the medley relay, it was another bitter Olympic experience. Hansen ultimately retired after the Beijing Games, content to explore other endeavors. Kitajima, meanwhile, took a sabbatical in 2009 before returning to the sport.

Eventually, the competitive urge got the best of Hansen and he returned to action in time to qualify for the 2012 Olympics in London. With lower expectations than his previous Olympic experiences, Hansen competed without pressure. He barely squeaked into the final of the 100 breaststroke, grabbing the last spot for the final. But racing out of Lane Eight, Hansen managed to collect the bronze medal, calling his latest piece of hardware “the shiniest bronze medal ever.” He also beat Kitajima in an individual Olympic race for the first time, with Kitajima finishing fifth. The medley relay on the last day of the meet saw Hansen win another gold with Team USA and Kitajima picking up silver with his Japanese teammates.

The final in London, much like Athens, wasn’t without controversy. Underwater video footage showed several swimmers, most notably South African gold medalist Cameron van der Burgh, performing several dolphin kicks off the start. Shockingly, van der Burgh later admitted to utilizing more than the single dolphin kick allowed by the rule change of 2005. The regulation change the governing body hoped would eliminate problems a year after Athens still hadn’t proven successful.

At the end of their final duel, Hansen and Kitajima put aside the digs that had been exchanged through the years and paid each other respect through Twitter. They also posed for a picture with one another after a press conference and exchanged a few words. Growing together in the sport clearly generated an appreciation level for one another’s talents.

“We had a good run against each other,” Hansen said.

With one race in Athens serving as a defining moment.