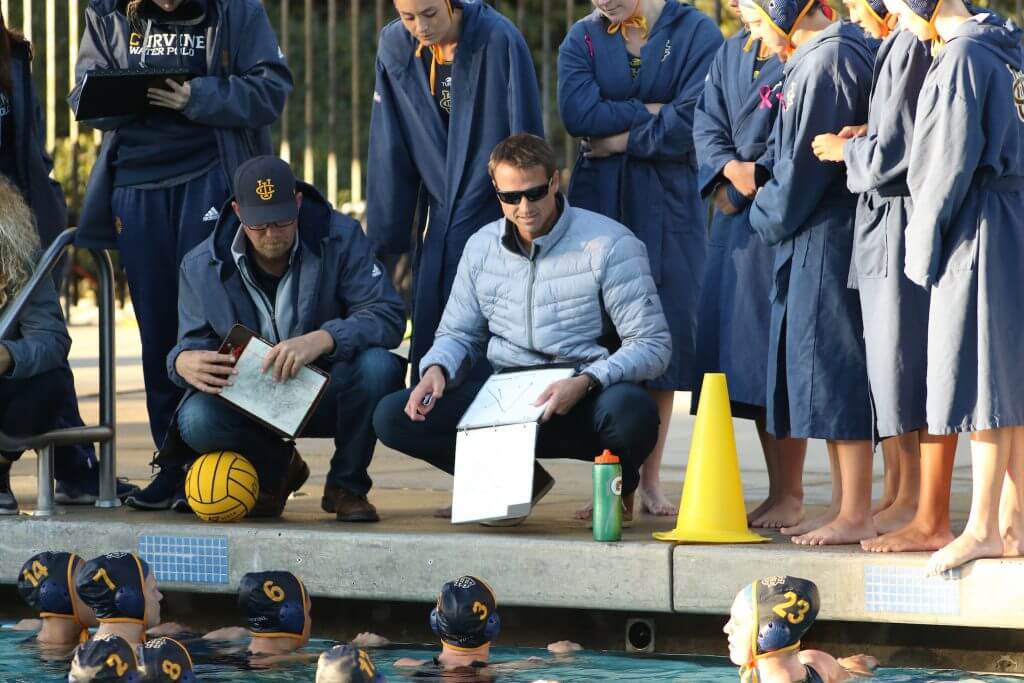

On The Record with Dan Klatt of UC Irvine Women’s Water Polo

Like his peers in the water polo coaching community, Dan Klatt has endured an unexpected stretch of inactivity brought on by the coronavirus pandemic—which as of today has infected more than six million Americans and killed almost 190,000 in the U.S.

For Klatt, head coach of the UC Irvine women’s team, everything stopped mid-March, when the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) suspended all competition. And, unlike most collegiate polo practitioners, he is also a key member of the U.S. national team program. As the top assistant to Adam Krikorian, head coach for the American women’s team, last spring Klatt was also prepping for the 2020 Tokyo Games, where Team USA was expected to contend for a third-straight Olympic gold—before the Games were postponed for a year.

For Klatt, head coach of the UC Irvine women’s team, everything stopped mid-March, when the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) suspended all competition. And, unlike most collegiate polo practitioners, he is also a key member of the U.S. national team program. As the top assistant to Adam Krikorian, head coach for the American women’s team, last spring Klatt was also prepping for the 2020 Tokyo Games, where Team USA was expected to contend for a third-straight Olympic gold—before the Games were postponed for a year.

[The Week That Was: It’s Tokyo 2021! Summer Games Postponed For First Time]

A former water polo Olympian himself—he represented the U.S. at the 2004 Athens Games—Klatt understands just how difficult it is to put those dreams on hold. In a conversation with Swimming World last week with twin four-year-old sons Luke and Skylar in tow, Klatt spoke about his extended hiatus from competition, the toll the virus his taken on his UCI players as well as Team USA athletes and the impact that Ted Newland, the Anteater’s legendary men’s coach, continues to have on his career.

– You’ve spent most of your life getting ready for polo. Now, because of the coronavirus, there’s no practice and no competition. How has this time been for you personally—and how are you filling the hours vacated by polo’s absence?

Obviously, I’ve gotten to see my family a lot more.

The biggest challenge is finding time for uninterrupted work. In regard to administration, refining our team, cultural and value expectations that we have, recruiting, creating recruiting presentations so someone can feel your program, expectations of our campus, your community within a zoom presentation… [that] can be challenging.

There’s certainly not deck time, but there’s Zoom meetings and increased integration with administrators. [They] work on a nine to five schedule, more so than coaches. [We] work random hours depending on when your practice is, what your travel looks like.

Photo Courtesy: UCI Athletics

You can work more than 40 hours a week and at two in the morning on a Saturday if that’s what’s called for. All these Zooms are now set up for various aspects of your program at different times during the day that may interrupt your normal recruiting schedule.

It’s been a transition to a different type of work and timeline—coupling that with my family. I’m extremely grateful for the time that we’ve gotten to spend together. I’m very lucky that my kids aren’t of an age yet where they truly understand what’s going on, or [how] their education is being interrupted.

Although it’s put a bit of strain on us, I’m thankful that it hasn’t put any strain on them. They’re happy and enjoying life and doing great.

It’s been great to be able to help my wife out. She shoulders this burden, and since we were in Olympic year, I was doing two jobs at once. She got a break earlier than she was expecting from handling that chaos.

– You not only focused on your main job leading the UCI women’s team, but also preparing the U.S. national team for a run to a third-straight Olympic gold. Then everything blew up in March.

From a UCI standpoint, starting with the end to the season—from a water polo perspective [it’s] disappointing for us in that our players were confident we were capable of competing for a national championship.

We had a game with UCLA coming up on the Friday before our season got canceled. [The team] was excited for that game and the opportunity for potential success. So, that was hard because we were getting better and building the way that you want to.

From a playing perspective—even though we didn’t know this was going to be the case—one thing we always try [is]: win or lose is we want to be playing our best water polo at the end of the season. It just so happens that—for this shortened amount of time—I think we would have gotten better. But, I feel like we were playing our best water polo when the season ended. So, rather than going away on a tough weekend, we were able to say: Hey, we were playing well and were in a really good place when things are out of our control hit.

From a training perspective, I want my athletes to have a healthy lifestyle and think about lifetime fitness. But the one thing I encourage during this time is solidify who you are as a person and the goals that you have outside of water polo. I think a lot of student athletes in any sport are connected to a self-image—I am a water polo player, I am a basketball player.

The truth is they are a lot more than that.

This is an opportunity to solidify those other things, and it could put them in a position of better mental health when they come back, feeling self-worth independent of sport while still being able to drive towards athletic goals when they come back.

– If expectations were met, the U S women would have achieved an historical accomplishment this summer in Tokyo. How do those athletes who took time off from college for the Olympics justify waiting another year to play for gold?

We had an opportunity to come back and train from June through mid-August. There was a lot policy in place to maintain safety—a lot of testing and so forth—but they did get to be around each other and train.

Klatt (with clipboard) and Team USA at the 2019 FINA Worlds. Photo Courtesy: Orange Pictures

We weren’t training for anything specific; we didn’t have any competition. But they created opportunities for themselves outside of water polo to work on career development. Some of the girls who took school off signed up for classes during the spring and summer to get themselves more prepared for that next step.

There’s a reason why those women are on that national team and why that national team has had success. They are remarkable human beings who handle adversity well. There’s no question they were upset and disappointed and confused about what to do in the future.

But, they’re resilient They’re doers, they’re achievers. They found other ways to achieve that lined up with their personal philosophies and goals.

– UCI’s Tara Prentice had such a great 2020 season—which ended abruptly. The question is: will she come back for a fifth year or call it an Anteater career?

Besides her ability to play water polo, Tara graduated this spring with two degrees. But, she’ll return to UCI to get her master’s [degree] in business entrepreneurship and innovation—and hopefully play next season.

It’s a great situation for her. Tara took it really hard [when last season ended]—she was as invested as possible in our program.

She’s an advocate for UCI at all times for the opportunity to win a national championship, and was one of the people who was making it happen—through her play and commitment. Previous to this year, she didn’t play center as much for us. She pretty much took the role as our primary center for most of this year—and just got better with that.

– Will it be difficult to manage your roster given a whole class year of athletes that may return this spring?

Yes and no. We want to have constant success; our goal is to always to get new players in that will push us upward. When we recruit people, it’s about more than just water polo. Do I think there’s going to be some challenges with numbers? Yes. I’ll start by saying we’re going to have 32 players on our roster this year, which is the most we’ve ever had in the history of our program.

And we certainly have some goals over the next few classes to adjust those numbers because that’s high for us. I believe we’ll manage fine, but we want to adjust to a lower overall number. The primary goal will always be to provide an excellent experience and support network for these athletes and—regardless of whether we have 32 or 25—we’re going to try to do that.

One of the challenges is [that] the Big West has made decisions in regard to roster limitations for conference contest in the upcoming year. So, it’s challenging in terms of creating the kind of experience that we want by including everyone.

Tara Prentics. Photo Courtesy: UCI Athletics

But, that’s one of the hard parts of collegiate athletics. There’s one team, one game and there’s only varsity. There’s no secondary opportunity to play.

You’d love to give everybody that opportunity, but it doesn’t always happen that way

– How does this effect the future, in particular recruiting?

I don’t think the future is ever totally clear. Sometimes people graduate early or they get hurt or various things like that happen. So, I look at this as another adjustment—maybe something a bit different than what was expected, but, it will work itself out and we’ll do what we have to.

It’s a challenge for young athletes that have aspirations of playing in a college program to find a spot. I’m sure they’re stressed about it because they’re not having the opportunity to play and prove themselves. But I think it’ll work itself out.

Can I say for sure that there’s not going to be one player out there, or a couple of players who miss opportunities as a result? No, I can’t say that for sure. Every program is going to handle this differently and I think as a sport, we all have to lean in right now to one another to help the sport as a whole and ensure its longevity.

– You mentioned longevity; George Washington eliminated its women’s program a few months ago. Should the polo community be concerned about Covid-19’s long-term effects to the sport?

I don’t sit around and worry about it because if it happens, it’s going to be out of my control. The best thing that we can do is be as professional as possible in terms of how we run our programs. Be as cooperative as possible with our colleagues at other institutions who may or may not need our help. And be a partner in our own athletic departments with our own administration to try to problem solve.

One thing the pandemic has taught me is I don’t think that we shouldn’t focus on doomsday. Everybody’s had to pause and search for good and great parts of their life. If for whatever reason my career as a water polo coach comes to an end, I’ve already gotten to coach incredible athletes for over two decades.

I’m pretty fortunate for that.

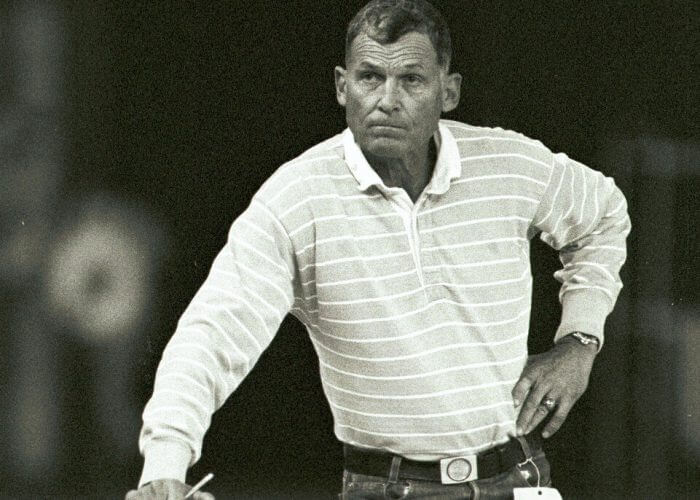

– In your career at Irvine you got to play for Ted Newland. Not only was he one of the greatest polo coaches America has produced, there’s a mythology around Newland the harsh disciplinarian which is at odds with Newland the person who cared very much about his players.

He was a very disciplined individual. I learned a lot that I use in coaching from him. I learned how you could be hard on players and love them at the same time. You didn’t have to be one way or the other. You could really push players to greatness and still show and reflect your love for them.

Ted NewlandPhoto Courtesy: UCI Athletics

Those are things that I think he did really positively. He was an example, [and] I try to be an example of the things I’m asking for. I try not to ask my players to do things that I’m not doing—well, I don’t do all their swim sets, I guess. So that’s a little bit of a lie—but I have done their sets and at some point in my life.

Our job—Coach John Vargas [Stanford men’s coach], myself, Mark Hunt [UCI men’s coach], and countless others who are still coaching or part of the game—the way Newland continues to live is through what we learned from him and, and how it integrates into our coaching.

It would be hard for someone that wasn’t one of his players or wasn’t within his circle to understand that other side of him, because he portrayed a pretty rough exterior.