On The Record With Alex Donis, Coach for Hialeah Storm and Hialeah High School Water Polo

Editor’s Note: Swimming World is down in Coral Springs, Florida for the annual South Florida International Tournament. Offered by Michael Goldenberg, his daughter Elina and extensive coaching staff from the South Florida Water Polo Club, this annual age group tournament—started in 2003 by Istvan Csendes, Jim Shoemaker and Bruce Wigo—draws teams from all over the East Coast as well as from the Bahamas, Calgary, Chicago, Peru, Puerto Rico, Rome and other locations.

HIALEAH, FL. The water polo club scene in Miami is as vibrant and diverse as the city that sustains it, with seven clubs recently participating in the 17th South Florida International Water Polo Tournament. All may lay claim to the Magic City’s multi-cultural identity, but perhaps no team is as truly embedded in the city’s fabric as the Hialeah Storm.

[At South Florida International Water Polo Tournament, Emphasis is on “International”]

Based in a Northwestern exurb of Miami, the Storm are a truly public club, part of an innovative and extensive aquatics program offered by the City of Hialeah Park District out of the Milander Aquatic Center. What makes the Storm so distinctive is that the program has been overseen since 2007 by Alex Donis, a devoted Miami native and Nelson Dominguez-Avila, a former Cuban national team member who represented his country in the 1976 and 1980 Olympic games.

If Dominguez-Avila represents the sizzle that only an Olympian can bring, it’s Donis who provides the grounding that makes the Storm a staple in national conversations about the growth of polo in South Florida. After picking up the game as a high schooler in Miami Lakes, Donis played two years for Brian Kelly at Iona before returning home, where he finished his degree at Florida International University (FIU), playing club ball for the Panthers.

A stint as a member of club polo under Miami legend Carroll Vaughan led Donis to a coaching career, first as an assistant at Barbara Goleman High School, his alma mater, then to Coral Gables, then to a head coaching position at Hialeah High School, where last year he led the Thoroughbreds to a state title in girls’ water polo—the first time a public high school captured a girls’ polo championship.

Donis observing his high school team in action. Photo Courtesy: Annie Tworoger / 3rd & Ocean

Last week Swimming World spoke with Donis about his devotion to growing the sport in his community, his relationship with Dominguez-Avila and his daughter Paolo Dominguez-Castro, one of the most promising polo prospects since Ashleigh Johnson, and prospect for the sports growth in South Florida.

– You are a high school coach but it’s all integrated in the work that you’re doing in the city of Hialeah to grow water polo.

It’s Hialeah High School, so it’s integrated in the community. Our baseball team or our aquatics programs are probably our number one. We’ve had historic baseball programs, and the past couple of years our aquatics program has raised a couple of eyebrows. We’ve won one or two club championships in several categories over several years. The International Tournament we won two years in a row (2017, 2018) for the 16U girls and then before that in the younger categories.

– How did it happen that Hialeah chose to sponsor a competitive age group polo club?

Before I went to Iona I was employed by the city as a lifeguard and I pushed to open the club a couple of times a week. I went away to school and they had somebody else run it who couldn’t handle it, so when I came back we pushed to open it again.

The person who was organizing the program ran into Nelson [Dominguez-Avila] and heard about his story so he brought him in. I told Nelson about my background and he agreed that we could work together.

10 – 11 years later that’s still true.

– So, it’s a bit of “Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside.” Where do you fit in this pairing?

We’re both Xs and Os guys; it’s just that he’s hindered by the language. I take his directions and translate that into English—while sprinkling some of my own stuff in there, too.

We’re kind of like Good Cop / Bad Cop. He’s been around the game for 50 years—so there’s nothing that he doesn’t know about water polo. And, as much as everybody thinks the game has changed, it really hasn’t. The essence of the game is still the same, and who knows that better than him?

– Where did you get your passion for the sport?

I played baseball all my life but decided I didn’t want to play anymore. I liked the water so I joined the swim team and I happened to have two amazing coaches. Cathy Redson swam for Auburn. She was a teacher at Barbara Goleman where I went to high school.

She was working for IBM and decided to quit and take a teaching job just to have better quality of life. She held the 200 and 400 IM records at Auburn for quite a few years and made the 1980 Olympic Trials—which she didn’t go to because of the boycott.

My water polo coach was Luke Sherlock, a local guy who played at St. Francis in Brooklyn. He knew Paul Becskehazy—two-time national champion at UCLA (1969, 1971). He’s the coach of Miami Beach international.

Your 2018 state champs – the Hialeah Thoroughbreds! Photo Courtesy: Miami Herald

I’ve had the privilege to work with the best coaches that we’ve ever had here in Florida. Then, add in the influence of ex-Cuban national team coaches and players—Nelson, Osvaldo Garcia, who was the coach of the 1991 Cuban team that beat the Americans in the Pan American Games. 90% of all the lifeguards on the beaches are ex-players. There’s a big Cuban water polo community and they really take care of each other.

One of my mentors is Felix Mercado at Brown—he used to be the coach at Ransom Everglades. He actually taught me how to tread water. I bounced around clubs in high school: I played at Miami Beach International and with Felix at Ransom for a little bit. He taught me how to tread water in the old Ransom pool back in the day.

I connected with Tim Tornillo—he’s been coaching for 35 years at Miami High School. He never played water polo but learned it fairly well. He’s the head of referees for high schools in Dade County. He was my club coach for a while. There’s Dave Tinkham, who’s been refereeing for 30 years. I’ve been lucky enough to be around a lot of really good water polo minds.

– Just how pervasive is the influence of the Cuban style of play on Miami water polo?

It’s all around [Miami]. I know Carroll [Vaughan] at Gulliver Prep has had Alain Gullien there—he’s a former Cuban pipeline player who’s been on her coaching staff. She pretty much did the Riptides on her own—there’s been other coaches who started with her—but she’s done a great job over there. Obviously, everybody knows the Johnson sisters—it’s actually the Johnson family. The second boy, Will, he would have been an amazing DI player if he hadn’t of ruined his shoulder in high school. Belen Jesuit won two titles (2015, 2016) and he then went to play at UF (University of Florida) and I haven’t really heard anything since.

– You mention University of Florida, which has a club team. What are the prospects for the Gators or any other Florida college starting varsity polo?

This summer I’m going to sit down and try to do a marketing job for this. For us to have college water polo in Florida will mean the world. If we did that, in ten years we’d be really close to the level of California, because sometimes our kids start late.

Now they’re starting a lot younger than before, but then they stop playing or they go away—because there’s nothing here college-wise for them. In California, they’ll have 4,000 fans at USC vs. UCLA games. That’s awesome! We don’t have that here. The people that watch are the parents.

Nelson Dominguez-Avila. Photo Courtesy: A. Donis

We’re trying to change that. Any time we go to a tournament, I tell my younger group that we’re going and they should come and support the team. It’s a way to mimic that exposure that all the other sports have.

– You can’t just have the Gators go varsity to make polo viable in Florida….

You need at least four [schools]. If we can open the eyes up of the big schools—maybe not even the big schools. Those medium schools like UCF (University of Central Florida), USF (University of Southern Florida) and FIU together with the big schools. We have some very good players and they’re in their universities and not even playing water polo. Or we lose them to somewhere else because if you come out for water polo you wouldn’t go [to a local school]. Partially it’s getting the numbers in—a good 80% of water polo players in Florida have a bright future, which is the same number the state of Florida pays for them to go to school. Wouldn’t those school like to have that money?

If you start a program you’re going to get most of those kids to go to your school. They’ll go to where they can play water polo.

– Is there a strong basis of swimming in the area?

FIU and [University of] Miami have swimming for women only. The do it to balance out Title IX. [Florida teams] have to have enough teams to make their own conference. They’re not going to spend the money to travel up to the Northeast or West Coast.

If FIU, for example, were to open a water polo program for girls, we’d be competitive year one with no scholarships. We’ll have 20 girls that you’ll bring into the school—we’re talking about talented players like Paola, the girls from Ransom, the girls from Gulliver. Some of these girls go to big-time private high schools and then they’ll go to Wagner or to St. Francis Brooklyn. You’re spending all this money for an education to go to a DII or DIII school—just because that’s the only place they can go play water polo?

– But until a couple of Florida schools launch varsity programs, you risk being like Austin College, which joined the MPSF for an affiliation—and doesn’t have any rivals in the state of Texas

You know why he’s going to get talent? Because they’re playing against the best.

– What hopes do your boys and girls have by way of prospects for scholarships to DI schools?

We need that first one to do it [make it to a DI school]. We thought we had it with Ashley Luy; hopefully it can work out in the future. She went to St. Francis University in Pennsylvania; it didn’t work out and she’s back home. That’s somewhat discouraging.

Paolo Dominguez-Castro. Photo Courtesy: Peter Laurence / USA Water Polo

Hispanic parents tend to hold tight to their kids—so breaking that culture is very difficult. This year, one of my boys is gonna [do it] because he’s being recruited by Washington and Jefferson, St. Francis Brooklyn and La Salle. I think he has thick enough skin to be able to hold up.

I went through with it; when you go away you miss home, you’re miserable. These kids don’t get to travel a lot—a lot of these kids never got on a plan until they joined our club. I know that Paolo, the first time she ever got on a plane was when she went to Colorado for 12U Rocktoberfest.

My first time I ever got on a plane was when I went to New York City to see Brian Kelly.

You need every year one or two kids to go—for example South Florida Water Polo has two or three kids that sign with colleges. They have a history of success, so the kids coming up see that; the parent see that and they’re more prone to push the kids more and for the kids to push themselves, knowing that other people from their club have made it.

– You’ve described your club as similar to the Commerce club that’s out in Los Angeles.

What Nelson and I have done is—if we can’t travel, we’re going to bring that high-level play here. He’s reached into his contacts, and Tuesday and Thursday nights we have the ex-Cuban National Team players come and play and beat up on our boys.

Three or four years ago we had five women staying with us from the Cuban National Team. They helped our girls a lot, just getting in the water with them.

Coach Nelson was on the national team for so long he’s made so many friends all over the world. [Guillen] the coach from Campus Roma, [Nelson’s] known him for so long, whenever we want we can go to Italy or they come to our pool.

The team from Chicago came the day before and trained with us for a day or two. We’ve had teams from Colombia come and stay for a week. Sometimes we can’t [travel] but he has so many contacts and been around the sport so long that we always have talented team coming here [to Miami].

Is there any place in the world more beautiful for polo? Photo Courtesy: Annie Tworoger, 3rd & Ocean

– Given that Miami is perhaps the southernmost big city in the continental U.S., there’s stronger connections to teams in the Caribbean and Latin America than in the North- and Southeast.

Talent is the same. [Navy in] Annapolis, they’re going to be 6-3, 220 lbs. The Puerto Rican kid is going to be 5-9, 165 lbs but they’re both going to be really good players. We use what we can and will play whoever’s coming to Miami.

We’re flexible and go to every local tournament that we can to keep our kids playing. But, we’re getting tired of this. The parents are bolder, more established and more well-off economically. They want to start expanding [opportunities for competition]—we’ll likely go to JOs this year.

Our problem is, that nobody goes to Jobs’ Whoever shows up at the zone qualifications gets to go because nobody wants to pay to go to California—unless its Ransom, Gulliver, Florida.

And in the words of Nelson, I’m not going to spend $1,000 to get [beaten]. he doesn’t believe in learning that way. You can learn, learn, learn and when you’re ready you can go compete. And we’ve proven it; the two or three players that we’ve sent [to California] can compete.

Riptides have been going to JOs for a very long time, so they have a ranking. If we go in as a new club. we’re going to be at the bottom of the barrel. We’ll probably have to play Stanford “A” or SOCAL “A” in the first game and lose 45-0.

10U, 12U or 14U is competitive. We’ll probably have to take 18Us. If you start as a new club you’re going to start at the bottom because you don’t have a ranking. Riptides have a ranking—they’re in the middle of the pack—and have a better chance of finishing higher in the tournament.

So, we just unite and go with them.

– And how has that worked?

It’s been good. A couple of years ago the [Riptide] girls won the gold bracket. The Riptides have been very good to us because they financially help some of the kids who don’t have money. And not just the parents. [Coach Vaughan] has done a good job of fund-raising for tournaments. And she’s been able to take some of our kids and help them out financially to play in different tournaments.

The sport is not expensive; all you need is a bathing suit and jump in. But, entry fees, travel, food, [local] transportation.

The sport is not expensive; all you need is a bathing suit and jump in. But, entry fees, travel, food, [local] transportation.

We’re a tight-knit community. Even though there’s many people who would love to come and help, it’s really just been him and me. His brother Oriel is involved—he’s family, he’s another Olympian, he comes in and helps out with the goalies.

When we first started, we were basically the support group of the doctors. We got all the eight, nine, ten year olds who were overweight. “The doctor says he needs to do a non-weight-bearing exercise because he needs to lose weight.” We would take anyone.

Now, we’re providing swim lessons right next to [our polo practices]. My group is right next to the swimmers; if I see a kid [swimming] who’s jittery or they run around and look athletic—and they can swim a length!—I put them into my lane.

– And now you’re drawing athletes who have legitimate Olympic prospects, including Paolo Dominguez-Castro.

When Paola was young, Nelson was worried. We looked for ways to streamline the recruiting process. “Why can’t we break the mold and make [coaches] come here?” he said. There’s schools popping up all over the U.S., and this is going to continue because polo is the fastest growing sport in America.

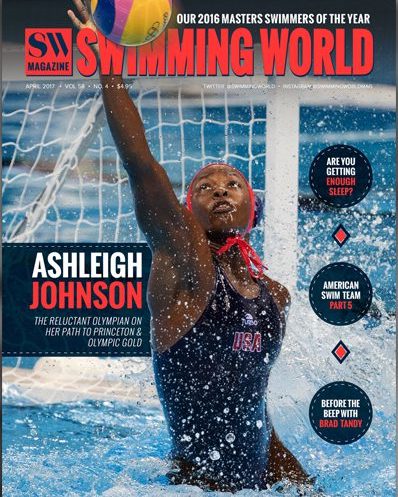

Ashleigh Johnson got in—breaking all the racial barriers—and she was accepted. Jackie Robinson broke all the racial barriers but his teammates didn’t really like him until later on in his career. When Nelson changed because [Ashleigh] was embraced—she was named Swimming World Magazine Women’s Water Polo Player of the Year—not only that, beating out Maggie [Steffens], the poster child for the sport in America.

And, it’s this girl from Florida that Paola’s played against. That was eye-opening for her dad.