Pablo Morales and One of the Great Feel-Good Stories in the Sport’s History

Pablo Morales and One of the Great Feel-Good Stories in the Sport’s History

Pablo Morales knows what it is like to have to wait for an Olympic Games. After debuting at the 1984 Olympics, Morales failed to qualify for the 1988 Games, but came out of retirement to reach and excel at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. Here is Morales’ story.

*******************************

The initial end, or what was perceived to be the end, wasn’t one of those feel-good tales which captures fans’ hearts. It was quite the opposite, actually, a brutal finish to what had otherwise been a remarkable career. While athletes in some sports can get away with a sub-par performance, rarely does swimming allow that luxury.

Think of the baseball diamond and the numerous times we’ve heard about a pitcher working his way to a victory without his best “stuff.” Maybe his curveball doesn’t feature its typical bite, but the ability to lean on pinpoint location or intelligent pitch selection enables the pitcher to fake his way through a start, and to a win.

A stopwatch sport such as swimming plays by different rules. Because the clock doesn’t lie, athletes at less than their optimal level are cruelly left to wonder: What happened? Why was I slower than last time out? Why did everything fall apart now, at the very moment I needed to be at the top of my game? Sometimes, the answers are hard to find. Sometimes, that’s just the way it is.

Ask Pablo Morales.

The son of Cuban-born parents, Pedro and Blanca, Morales was introduced to swimming at a young age, largely because his mother had a near-drowning experience before moving to the United States. Although brought to the sport for safety reasons, Morales almost immediately showed a tremendous feel for the water.

It wasn’t long before Morales had developed a strong reputation as an elite performer on the junior level and earned a scholarship to compete for the high-powered program at Stanford University. As a collegiate athlete, however, is when Morales became a global phenomenon. Just after his freshman year at Stanford, Morales broke a world record in the 100 butterfly at the United States Olympic Trials, and then won three medals at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles.

“(My parents) worked really hard so that they could provide that for us,” Morales said. “I think because of that, we lived fairly comfortably, and we were able to dream big. And I was fortunate that I latched on to something that I did fairly well, and I was driven to do.”

Morales’ own words don’t do justice to his vast talent. While a retaliatory boycott by the Eastern Bloc nations diluted the talent at the 1984 Olympics, as was the case when the United States boycotted the 1980 Games in Moscow, it was still a launching ground for Morales. He won silver medals in both the 100 butterfly and 200 individual medley and helped the American squad capture the gold medal in the 400 medley relay.

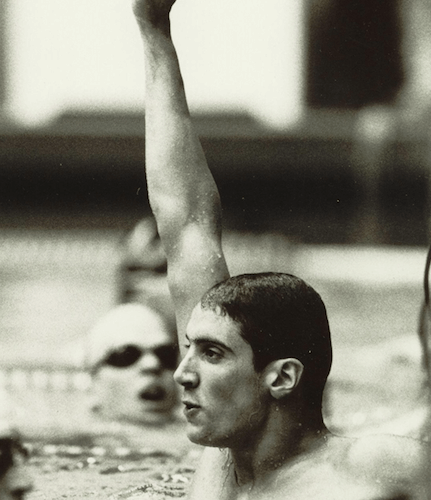

Photo Courtesy: Tim Morse

His meeting with West Germany’s Michael Gross in the 100 butterfly marked the first of several clashes. Widely considered the best swimmer in the world at the time, Gross needed the perfect performance to better Morales in Los Angeles, which is exactly what he delivered with a world-record effort of 53.08. Morales was also under the previous world record, going 53.23, and as a 19-year-old, there was little doubt Morales was on the verge of greatness, perhaps as one of the finest swimmers produced by the United States.

By the end of 1985, Morales had picked up a pair of individual gold medals – in the 100 butterfly and 200 individual medley – at the Pan Pacific Championships, outings which led to a superb 1986 campaign. Not only did Morales reclaim his world record in the 100 butterfly, his swim of 52.84 endured as the global standard for nine years. More, Morales won his first world title, prevailing in the 100 butterfly ahead of American teammate Matt Biondi. He followed in 1987 with another 100 fly win at the Pan Pacific Championships.

All along, Morales was sculpting – arguably – the finest collegiate career ever produced by a man. En route to leading Stanford to three NCAA team championships, Morales won the 100 butterfly and 200 butterfly in each of his four seasons, and won the 200 individual medley in his final three years. The 11 individual NCAA crowns made Morales the most-decorated male swimmer in college history, having bettered the 10 titles won by the University of Southern California’s John Naber in the 1970s.

Considering the momentum built by Morales on both the international and collegiate stages, there was little reason to doubt his qualification for the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. But as the United States Trials in Austin, Texas approached, Morales took a measured approach to the selection meet.

With only the top-two individuals selected for the Olympics in each event, the United States Trials are considered by many to be more pressure-packed than the Games. Third place is no better than last, and a hundredth of a second can be the difference between a lifelong dream coming to fruition or a lifelong dream shattering into pieces. Many years, the third-place finisher at the American Trials would have contended for the Olympic podium.

“There are a lot of people who second-guess our system because it pays no special regard to world record-holders,” Morales said heading to the 1988 Trials. “Other countries assure their stars of a place on the team. But our system gives the late bloomers a chance. It puts you in a similar situation to what you’ll face at the Olympic Games. Swimmers must perform under that pressure. It’s hit or miss, do or die. But that’s the kind of athlete the U.S. wants in the Olympic Games.”

For Morales, the Lee & Joe Jamail Swim Center on the campus of the University of Texas became a disastrous setting. After moving into the final of the 100 butterfly as the No. 2 seed, Morales was denied a trip to Seoul in the final of his best event. More than a half-second off his world record, Morales finished behind Biondi and Jay Mortenson in what remains one of the biggest surprise misses in United States Trials history. Morales followed with another third-place finish in the 200 butterfly and didn’t advance out of the preliminaries of the 200 individual medley.

The end of his career – so it seemed – came earlier than expected. Morales wasn’t the only person surprised by the results. His shortcoming was the talk of Trials, so much so that several coaches spoke of their desire to see Morales on the American squad. While Morales was a Team USA veteran and leader, he was also one of the most likeable swimmers in the country.

“You’re thinking that you have a chance to make the Olympic team, but then all of a sudden there’s a really stark, abrupt ending to one’s swimming career,” Morales said. “It’s over. Boom. You’re done. Because you don’t think you’re going on another four years.

“The 100-meter butterfly is my forte. It has been throughout my entire career. I felt it was my best shot to make the team. Over the years, I’ve taken a great deal of pride in this event and … That’s the type of meet it is. Favorites don’t always make it. Underdogs surprise you. That’s the beauty of this meet.”

When Morales left Austin, he also left his sport behind. He traveled East, started law school at Cornell University and began eating without care, a decision which caused the disappearance of a once well-defined body. For three years, he was away from the pool, that place which had yielded so much success and joy, but also some real pain.

About a year before the Barcelona Games, Morales’ mother lost her battle with cancer and Morales lost one of the most important people in his life. As she was dying, he decided to give the sport one final go, to see if he could rekindle any of his past magic. He knew there were no guarantees, but this journey was one he wanted to undertake.

Working with his college coach, Skip Kenney, Morales had to get into shape in a short period of time. Fortunately, he was able to make large gains and realized early on in his comeback that his decision was the correct on. He had to try.

“The key for me was realizing whether it was something I truly wanted to do again,” Morales said. “And once I got back into it again, I was like, ‘Oh, this is right. This is good. This is what I wanted to do.’ It was wonderful being back in the water again and training, getting in shape and having that quantifiable goal to go after.

“I just decided in August after my mom died, I wanted to give it another try. I was older and more mature. I could handle failure. When someone you love dies, the pain and sense of loss, it never really goes away. That was a very difficult time for us. My mom was very supportive of my swimming career and it was very meaningful for her… I’d actually decided to make a comeback prior to her passing away. She knew about it.”

Morales’ performance at the United States Trials in Indianapolis was a fairytale of sorts. Although he was more than a second slower than his world record, Morales qualified for the 1992 Games in Barcelona by finishing first, a hundredth of a second quicker than Mel Stewart. Fellow competitors were overjoyed to see Morales back on the Olympic Team.

In the stands, Pedro Morales held a picture of his wife and Pablo’s mother in the air as his son secured a berth to Barcelona. The image was touching, and tears flowed freely among members of the Morales family and beyond. Yet, qualifying was just the first stage of Morales’ journey. Once he qualified, there was no reason to believe he couldn’t add another chapter to his comeback tale.

“I’d never count out somebody as talented as Pablo,” said Mark Schubert, who guided the United States women at the 1992 Games. “But I thought it was going to be a real tough comeback. Then, I saw him swim at the U.S. Open meet in December and it was obvious that he was going to get himself really fit and that the talent was still there. I think the sky’s the limit. I think he can accomplish anything . . . He’ll definitely be near his best time, if not better, and that should be good enough. Everybody on the team wants him to succeed. There’s nobody that the team feels deserves it more than him.”

As Barcelona approached, Morales was frequently asked about what took place four years earlier, about the death of his mother and about his comeback dreams. Legendary Olympic historian and documentarian Bud Greenspan even had cameras following Morales for his upcoming documentary on the Barcelona Games. Never did Morales try to be anyone but himself. On the night of the 100 butterfly in Seoul, Morales admitted to leaving the room when the event came on television.

“During the Seoul Olympics, I really didn’t watch much of the Games, which, for me, is unusual because I’m a very big sports fan,” Morales said. “I enjoy an athletic spectacle such as the Olympic Games. I did catch a little of the Games, but I didn’t watch my race. It wasn’t my race. Sorry about that. It’s melodramatic, I know, but it hurt not to be there.”

Some of the competition Morales knew during his heyday was gone by the Summer of 1992. Gross retired after the previous year’s World Championships and Biondi was no longer contesting the 100 butterfly. Still, when Morales climbed the blocks in Barcelona, he wasn’t working against a weak field. Suriname’s Anthony Nesty returned as the defending Olympic champion and Poland’s Rafal Szukala was a European champion.

Photo Courtesy: Nebraska Athletics

Known for his early speed, Morales had the lead at the turn and while he started to fade at the finish, he found the wall early enough to fend off Szukala, with Nesty on the podium for a second straight Olympiad with the bronze medal. After hitting the wall, Morales recognized an atmosphere similar to 1984, when he placed second to Gross.

“This was my time at last,” Morales said. “I guess I wanted to hear a reaction first before I turned around. There is a moment of silence, and it was eerily reminiscent of the silence I heard at the 1984 Games, when the crowd was silent except for the German contingent when Michael Gross had won. I wasn`t going to turn around too quickly. I wanted to gather my composure and then turn around to see the scoreboard. I searched for my name and looked for the numbers.

“I was prepared not to win this race. You imagine every possible outcome: winning, losing, not making finals. The reason I came back was for the Olympic experience. This is an arena where the best come together, each with a dream of winning a gold medal. Every athlete really yearns for a competition such as this. That`s something that`s always been within me, even though I had a preoccupation with legal studies. I know it was always within me.”

The thrill of Morales’ victory grabbed headlines in Sports Illustrated and major newspapers around the United States. The significance of his triumph also affected former rivals, including Gross.

“I cried when he won,” Gross said. “I have wanted him to win a gold medal ever since I beat him.”

Before the Barcelona Games, Morales was viewed as a great in United States swimming lore. He was an Olympic medalist, a world-record holder and NCAA legend. But after Morales conquered the world in 1992, his story took on a fairytale quality, elevating his status further. His tale had a bit of everything: A comeback from vast disappointment, set against the backdrop of family grief.

“Given that three years away from the sport, I think I was able to achieve a certain sort of perspective about why I trained, why I was a competitive swimmer,” said Morales, who has spent more than a decade as the head coach of the women’s program at the University of Nebraska. “For me, the greatest source of fulfillment was setting a goal and making progress toward achieving that goal.

“People were affected by the comeback. I looked at going to the Olympics as a chance for glory and fulfillment. That is what every athlete is seeking, a chance to prove himself on one day against the best competition in his sport. That is the ultimate.”

I think there is a mistake and his mom died one year before Barcelona, not Seoul, otherwise the story doesn’t make any sense.

Timeless, great stuff !

Very nicely written piece. As a former Stanford butterfly swimmer myself, I have been proud of Pablo and his accomplishments for a long time. It’s great to remember his story.