Olympic Perspective: Cecil Healy, Aussie Swimmer No2, A Tale Of Sportsmanship & Loss 108 Years On

Olympic Perspective from the Past for the Present generation coming to terms with a shift from Tokyo 2020 to 2021 that offers hope not finality

When Swimming World trawled back in history to find some of the stories of the past that contribute to our series in search of perspective for the present season of social-distancing, pool and program closures and cancellations and postponements of events that have turned the sporting seascape and landscape into a desert, the story of Cecil Healy was an obvious one to look at. This week marked the 108th anniversary of the Stockholm 1908 Olympic 100m freestyle final in which American Duke Kahanamoku claimed gold because of an act of sportsmanship, central which was the insistence of Healy and mates that Americans who failed to show for the semi-finals due to a misunderstanding about the schedule should be allowed to race in the final. Healy took silver, six years before his death in the Battle of the Somme, 1918. Here’s a tribute to him.

- The Tokyo Postponement in Perspective: What Has (and Hasn’t) Stopped the Olympics

- Olympic Perspective: The Heights Of Hveger Never Seen & Other Careers Lost To War

- Olympic Perspective: Alfred Nakache, The “Swimmer & Survivor of Auschwitz”

- Olympic Perspective: Pablo Morales Knows About Olympic Waiting Game

Healy The Hero Who Saved Duke Kahanamoku’s First Gold At His Own Expense

Cecil Patrick Healy will forever be Australian Swimmer No 2. Down Under, each swimmer who makes the national team, the Dolphins in the parlance of more recent times, gets a numerical badge of pride for the present and, when that became the past, the pantheon.

Healy’s days were also numbered by War. On August 29, 1918, six years after lifting Olympic gold and silver at Stockholm 1912 at the age of 31, he was killed in action in the Battle of the Somme during an attack on a German trench. He was 36.

His tale is one of personal achievement, perseverance, pioneering, chances denied, true sportsmanship and tragedy.

Healy’s Olympic swimming career included three Games missed through no fault of his own, two because of lack of funding, the other because of the cancellation of the 1916 Games (due to have taken place in Berlin) during the Great War, or First World War, which lasted from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918.

Contemporaneously but prematurely known as “the war to end all wars”, WWI involved more than 70 million military personnel, 60 million of those European. One of the largest wars in human history, it was also one of the deadliest conflicts, with an estimated nine million combatant and seven million civilian lives taken.

Healy’s was among the last lives taken in battle but the genocide that followed WWI and the 1918 ‘Spanish ‘flu’ influenza pandemic that was all the more devastating on the back of war and the conditions of life that flowed from it, caused another 50 to 100 million deaths worldwide, depending on which estimates you loo at.

Olympic Perspective

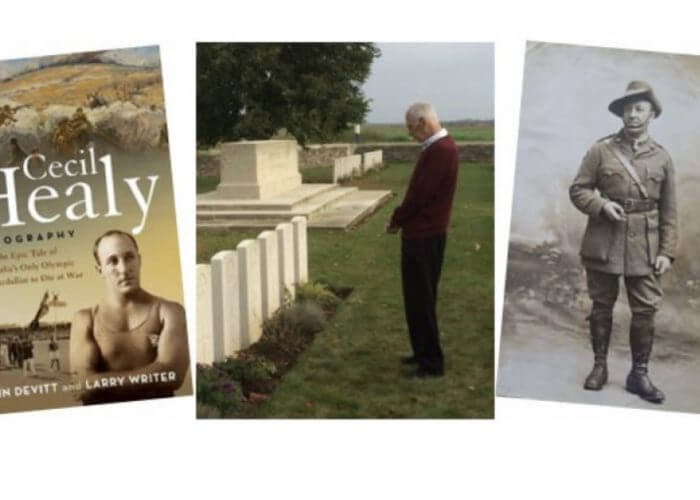

Cecil Healy – a Biography – Photo Courtesy: Ian Hanson

Healy made the Intercalated Olympic Games of Athens 1906, took bronze in the 100m freestyle an arm away from the first head-to-head Olympic sprint duel-in-the-pool between American Charles Daniels and Hungarian Zoltan Halmay.

Two years on and Healy was in peak form. Alas, he could not scrape together the funding to make it to London 1908 in days long before the birth of the subsidised world of today, with state, federation and Olympic committee dollars from purses public, broadcast and sponsor delivered a greater certainty that being good enough would get you there.

Healy made it back for Stockholm 1912. He was there to watch the dawn of women’s swimming at the Olympics, there to see compatriot Sarah Frances “Fanny” Durack become the first woman to win an Olympic swimming title, over 100m freestyle, after she battled not only the first women competitions to grace the Games but also the men who told her she could not compete.

In a ‘fast-facts’ file on Swimming Australia‘s website, the first three entries pertain to this story of pioneers, starting with “Swimmer No1”:

- Fred Lane won Australia’s first and second ever swimming gold medals at the Olympic Games in Paris in 1900. The first was in the 200m freestyle and the second the 200m obstacle race.

- Fanny Durack was the first women to represent Australia at the Olympic Games, winning gold in the women’s 100m freestyle in Stockholm in 1912.

- Australia’s first ever Olympic swimming relay gold medal came in 1912 when Cecil Healy, Harold Hardwick and Les Boardman joined up with Malcolm Champion from New Zealand for an Australasian victory.

The son of a barrister, Healy was born in Darlinghurst, an inner-city suburb of Sydney but the family moved to the rural town of Bowral, where young Cecil attended primary school in the 1880s.

There was no internet nor any other mass-channel for spreading the news back then but Healy grew up at a time of great invention, inventiveness and immigration:

- It was a decade in which more than half a million Swedes emigrated to America; when Chinese, Scandinavians and Irish immigrants laid 73,000 miles of Railroad tracks in America; when Friedrich Nietzsche published Thus Spoke Zarathustra; Mark Twain published Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; Carlo Collodi published The Adventures of Pinocchio; Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote The Brothers Karamazov; Robert Louis Stevenson published Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde; Arthur Conan Doyle published his first Sherlock Holmes tale; and Henrik Ibsen published Ghosts.

- The Eiffel Tower was inaugurated on March 31, 1889 thus becoming the tallest structure in the world, after the Home Insurance Building, the first skyscraper in history, had become the tallest man-made structure ever built in 1885.

- When Healy was a baby, William Edward Ayrton of London, England and John Perry of Garvagh, County Londonderry, Ireland, build an electric tricycle with a range of 10 to 25 miles, powered by a lead acid battery.

- And before Healy went to school, a man called Galileo Ferraris of Livorno Piemonte, Kingdom of Italy, formed the the concept of a rotating magnetic field. He applied it to a new motor. “Ferraris devised a motor using electromagnets at right angles and powered by alternating currents that were 90° out of phase, thus producing a revolving magnetic field…” By then, another bloke, Nikola Tesla, had independently reached the same concept and was seeking a patent.

Healy: First Sub-Minute Man In Contemporary Notes Before Records Began

The race for progress was all about by the time the teenage Healy moved to Sydney in 1896, joining the East Sydney Swimming Club, of which Frederick Lane was also a member. Healy also joined the North Steyne Surf Lifesaving Club and attended St Aloysius’ College in Sydney in 1896. He’s remembered there to this day in the Roll of Honour and via the Cecil Healy Plate given each year to the winner of the inter-house swimming competition.

In 1904, Healy swam the fastest ever time in the 100 yards freestyle: 58 seconds. It would be four years before FINA was formed to establish standardisation and begin to recognise official world records. Australians got to hear about something called the Olympic Games in St Louis in 1904 but there was neither funding nor organisation to contemplate getting a team to a Games that featured just 42 athletes across all sports from outside the United States.

Healy matched that 58s timing in the 110yd freestyle for his first Australasian Championships title in 1905. That never went down as the first sub-minute 100m / 110yd freestyle because of a lack of proper time-keeping, measuring of pools and the checks and balances that are a part of rules we recognise today. Even so, contemporary notes suggest that Healy was a sub-minute pioneer 17 years before Johnny Weissmuller made the feat official.

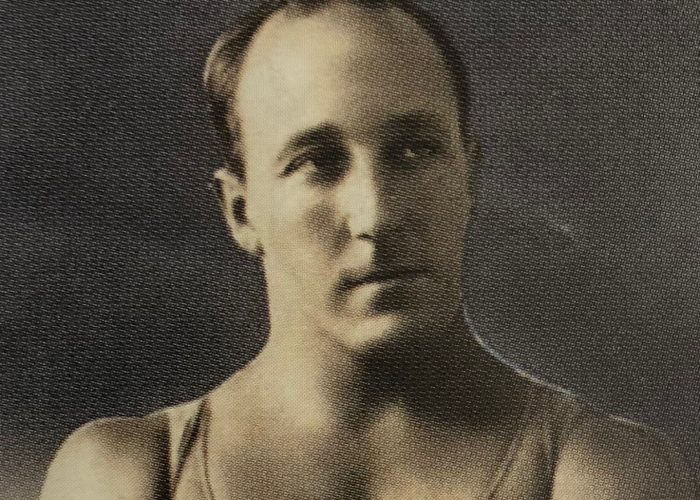

Photo Courtesy: Hanson Media Group

A proponent of ‘new crawl’, Healy raised eyebrows among the classicists of the day who perceived it to be “inelegant”, with “too much splash” generated by a high-elbow recovery of arm and an entry of hand ready not to wade but pull.

Those were the dying days of Trudgen, a swimming technique characterized by the turning of the body from one side to the other and the alternating release of the arms above the water, accompanied by a slight movement of the legs resembling alternating kicks. The trudgen was also known as “the racing stroke” and the “East Indian stroke” and was named after the English swimmer John Trudgen, who adapted the then traditional sidestroke.

In 1906, Healy took his crawl to Athens 1906 as one of only five Australian athletes for whom the necessary funding was allocated. After his bronze behind Daniels and Halmay, who’d topped the race in 1904, too, Healy toured Europe and spread the word on crawl.

He raced in Hamburg, winning the Kaiser’s Cup, in Belgium, the Netherlands and Britain, where he claimed the win over 220 yards freestyle at the British Championships but was thwarted by Daniels once more over 100 yards.

In 1908, Healy won the 110 yard freestyle but a lack of funding kept him away from London 1908. Her persevered and claimed more Australian titles in 1909 and 1910, extending his repertoire up in distance by 1911, when Healy inflicted the first defeat on another Aussie-swim-legend-to-be, Frank Beaurepaire, over 440yd. Healy also knew defeat himself that year, when Harold Hardwick claimed his 110yd crown.

In 1912, Healy came third in the 110, 220 and 880 free at the Australasian titles and was selected to race at the Stockholm 1912 Games for “Australasia”, which combined athletes from Australia and New Zealand in the victorious 4x200m freestyle relay.

How Healy Saved Duke’s Golden Debut

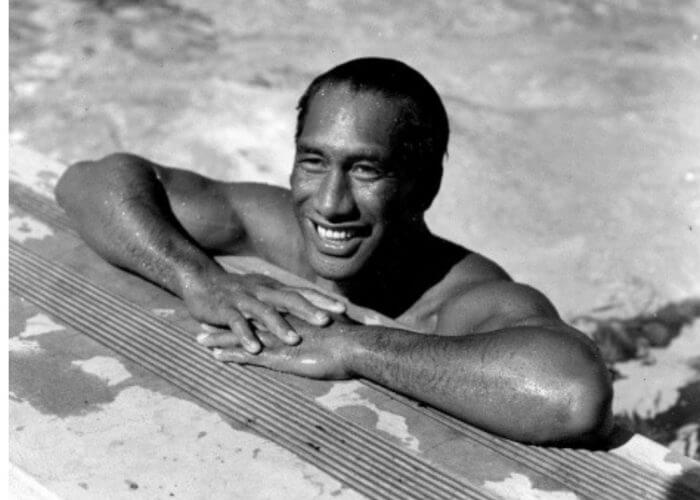

Duke Kahanamoku – Photo Courtesy: International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF)

At the Games in Stockholm that marked the arrival of women in Olympic swimming, Healy, fellow Australian Bill Longworth and American newcomer Duke Kahanamoku qualified for the semi-final of the 100m free.

Kahanamoku was king but controversy followed.

Healy and Longworth qualified for the final in the first semi but the three Americans, who were scheduled to qualify in the second semi-final did not show up. It was tJuly 7, 1912 and the final was not scheduled to take place for another three days.

Their team management had made an error and misread the schedule. They were to be ruled out of the final but it was Healy who intervened and assisted in an appeal to allow the Americans to swim a specially arranged second semi-final.

In their 2019 book “Cecil Healy – A Biography”, John Devitt, the Olympic 100m freestyle champion of Rome 1960, and co-author Larry Writer, wrote:

“Healy refused to swim in the 100-metres final unless the Duke, the favourite, was allowed to compete. The great Hawaiian had missed his semi-final after a misunderstanding over the starting time. Healy’s gesture cost him victory but earned him a place in sport’s pantheon of true champions.”

David Hurley launches the biography of Cecil Healy – Photo Courtesy: Ian Hanson

Protests followed but the second-chance semi was staged and Kahanamoku went through. In the final, on July 10, 1912, the American dominated for gold by a margin of 1.2s over Healy, who would have been Olympic champion had he not been such a good sport and a champion in a life cut short before his time.

In 2018, the Australian Olympic Committee created a Sportsmanship Award in honour of Healy to mark the 100th anniversary of his death.

In the 400m freestyle, Healy set an Olympic record of 5:34 at the helm of the fifth heat. He clocked 5:37 for fourth place in the final, Canadian George Hodgson on 5:34 to take the distance double after 1500m gold four days earlier. Harold Hardwick took the bronze, behind Britain’s John Hatfield.

A day after the 400m, Healy would get the one Olympic gold of his career, as a member of the 4×200 m freestyle, with Harold Hardwick, Leslie Boardman and Malcolm Champion holding off the USA team led by Kahanamoku.

After the 1912 Games, Healy toured Europe, as he had in 1906. He lowered Beaurepaire’s 220-yard Australian record by more than three seconds in Scotland.

On his return home, Healy announced that he would retire but did not rule out a return for the really in 1916. Nor was he gone from swimming: he encouraged people to make swimming a part of their daily exercise routine and lived by his word. An active lifesaver at Manly beach, he won the Royal Humane Society silver medal for saving numerous surfers.

In March 1913, following an article he had written earlier that year on the history of “the crawl” for the Sunday Times, he published a paper on “The Crawl” in The Referee. An adapted form of the article was later put to a 20,000 run and released, free of charge, in Britain under the titles “The Crawl Stroke“.

Healy was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame as an “Honor Swimmer” in 1981.

In his first Remembrance Day tribute in Canberra last year, Australian Governor-General David Hurley AC DSC, paid tribute to Healy, who remains the only Australian Olympic gold medallist to lose his life in the line of duty.

Here is a fine tribute from Ian Hanson, Swimming World Oceania Correspondent.

In Memory of Cecil Healy, a poem from England that transcends borders:

Cecil Healy’s Grave

For the Fallen

By Laurence Binyon

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children,

England mourns for her dead across the sea.

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free.

Solemn the drums thrill; Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres,

There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted;

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables of home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England’s foam.

But where our desires are and our hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the Night;

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain;

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.