Munich Games 50th: The Missing Gold Of Rick DeMont; How A Teenager Was Let Down By Those Charged To Protect Him

Munich Games 50th: The Missing Gold Of Rick DeMont; How A Teenager Was Let Down By Those Charged To Protect Him

The 50th anniversary of the 1972 Olympic Games is a week away. There will be celebrations of Mark Spitz’s iconic seven-gold show. We’ll remember the precociousness of Shane Gould, the Australian teenager whose five solo medals remain a female standard. And we’ll honor the backstroke greatness of Roland Matthes, who doubled in his events for the second straight Olympiad.

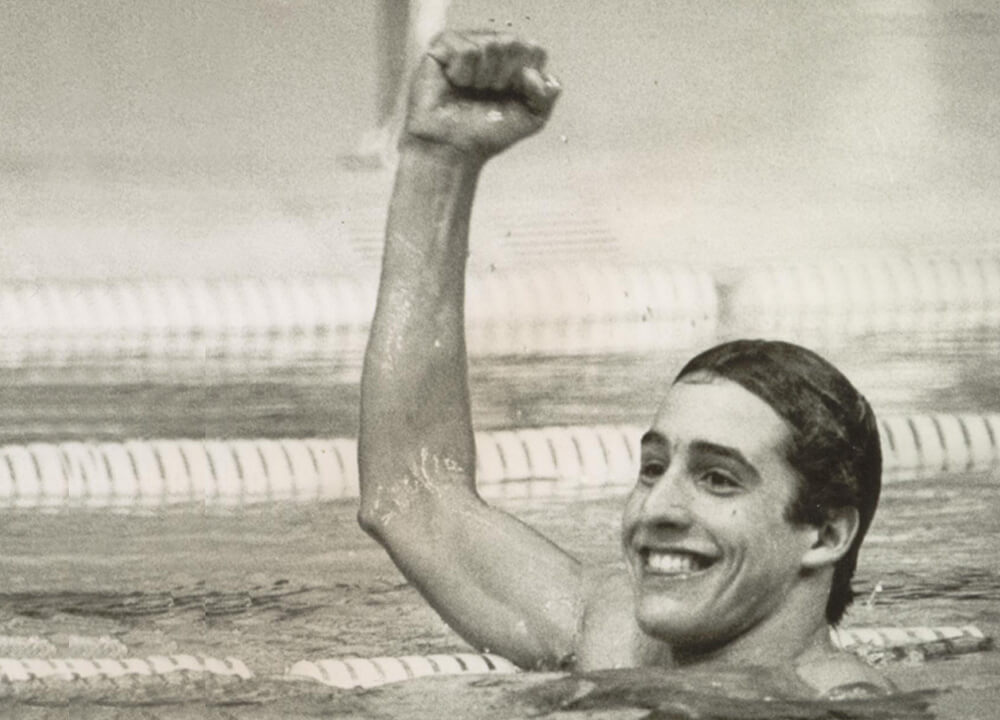

Golden anniversaries are supposed to be joyous occasions. But there is nothing celebratory about what about what Rick DeMont endured in Munich. DeMont’s story, a half-century later, remains a sporting crime, a young man deprived of his rightful place in history. A young man let down by the adults around him. A man, defined by extraordinary achievements in the coaching world, who does not possess what is rightfully his.

When DeMont arrived in Munich, he was one of the younger members of the American delegation. Spitz, of course, was the highest-profile name on the roster. Yet, DeMont was a leading contender for a pair of Olympic titles – in the 400 freestyle and the 1500 freestyle. In the longer event, DeMont was the world-record holder, having set that global standard at the United States Olympic Trials. Munich, quite simply, was the stage to verify his status as the world’s premier distance freestyler.

The 400 freestyle was DeMont’s first event of the Games, held a few days into the competition. By the time DeMont took the blocks, he had handled the necessary pre-Games protocols. Most critical for the 16-year-old was a meeting with United States Olympic Committee officials to complete paperwork regarding his asthma, and to denote the medications (Marax, Actifed, Sudafed) he took for the condition. At no point did officials raise any concerns.

Photo Courtesy: Swimming World

Once the 400 freestyle started, the race evolved into a two-man battle between DeMont and Australian Brad Cooper, considered the favorite for gold. Cooper held the lead for much of the race, including into the final lap. But relying on his greater closing ability, DeMont cut into Cooper’s lead and drew even as the wall neared. At the finish, the gold medalist could not be determined by the human eye, and it wasn’t until the scoreboard flashed the results that a victor was known. At the touch, it was DeMont who prevailed in 4:00.26, with Cooper the slightest margin back in 4:00.27.

“I’ve been swimming come-from‐behind style since I began,” DeMont said of his late rally. “At the United States Olympic Trials, I was strictly thinking of the 1500 meters. Now, I love the 400, especially after tonight.”

Since DeMont was stronger in the 1500 freestyle, a second gold seemingly awaited the American later in the meet. Any chance at a double, however, quickly evaporated. And so did the gold medal that DeMont had captured in the 400 freestyle. Following his apparent triumph in the eight-lap event, DeMont was informed that his post-race doping test revealed trace amounts of Ephedrine, a banned substance.

The presence of Ephedrine in his doping sample was hardly a shock, as the substance was contained in his asthma medication. The substance was also not supposed to be an issue, as USOC officials – following the processing of DeMont prior to the Games – were charged with the task of informing the International Olympic Committee of DeMont’s use for medical reasons. If the IOC had a problem with the substance, it would have notified the USOC and an alternative option would have been sought. The USOC, however, never engaged with the IOC on the topic.

“It was (the USOC’s) responsibility to let me know there was an illegal substance in my prescription and either get it cleared or find an alternative,” DeMont once said. “They failed to do it. I was only 16 years old. I relied on those officials to tell me what I could take, but somehow, I ended up paying the price. I guess it was easier to hang a 16-year-old kid out to dry than to tell the truth.”

Days after his apparent gold-medal swim, DeMont was stripped of his title, with Cooper elevated to the status of Olympic champion. As ugly as the situation was at that moment, it was about to get nastier. After DeMont’s urine test revealed the Ephedrine in his system, U.S. team doctors confiscated the medication DeMont was taking for his asthma. More, at a hearing with IOC officials, DeMont was peppered with questions while Team USA doctors sat quiet, offering no assistance or defense. Simply, DeMont was abandoned by the adults around him – those who dropped the ball in the first place and now refused to accept their role in the mess.

“It’s a gross injustice,” said U.S. Men’s Coach Peter Daland of the IOC’s decision to strip DeMont of his gold medal. “Young De Mont was robbed, robbed because of the mistakes of adults. (USOC personnel) knew of the boy’s medical record because he had it on paper. They said nothing to me or his head coach about it. The communications were atrocious. It’s a young man being punished when he should be applauded. He overcame asthma to win a gold medal and took nothing more than his doctor ordered.”

As the IOC weighed his case, DeMont qualified for the final of the 1500 freestyle. Even if his pursuit of an overturn of the 400 freestyle verdict failed, at least DeMont would get the chance to compete for another gold. Ultimately, that opportunity never materialized. As DeMont was preparing for the final of the 1500 freestyle and the possibility of redemption, United States assistant coach Don Gambrill, with tears running down his cheeks, approached the teenager and told him the IOC ruled he was not allowed to compete.

Reports from Munich indicate that multiple options were considered in the DeMont case. One scenario was to allow DeMont to race in the 1500 freestyle. Instead, the IOC went with the harshest choice, and banned DeMont from the Games. DeMont left Munich devastated. In the minds of many, he hadn’t committed an error, but instead was let down by officials who were supposed to provide support.

A year later, at the inaugural World Championships in Belgrade, DeMont engaged in a rematch with Cooper in the 400 freestyle and became the first man to break the four-minute barrier. DeMont was timed in 3:58.18, with Cooper also cracking the four-minute barrier in 3:58.70. DeMont also went under the existing world record in the 1500 freestyle but had to settle for the silver medal when Australian Stephen Holland blasted an even quicker time.

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

Following his competitive days, DeMont emerged as one of the world’s finest coaches. For years, he worked alongside Frank Busch at the University of Arizona, where he eventually served as head coach from 2014-17. During his coaching tenure at his alma mater, DeMont mentored a bevy of NCAA champions and became well known for establishing a pipeline between the program and South Africa. It is DeMont who is primarily credited for molding the South African 400 freestyle relay that won gold at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens behind the efforts of Roland Schoeman, Lyndon Ferns, Darian Townsend and Ryk Neethling. DeMont served as a South African coach in Athens and coached every member of that relay.

In 2001, DeMont was provided with a measure of vindication when the USOC honored him at a banquet and presented him with a black leather jacket given to all 1972 Olympians. The IOC, however, has not taken steps to restore DeMont’s gold medal, despite several conversations on the topic through the years.

“I don’t need any ceremonies,” DeMont said. “I don’t need any hoopla. I just want the IOC to repair the historical record.”

What happened was a tragic case of injustice towards an innocent great young athlete. I was there to witness DeMonts great come from behind victory. Lets not forget Demonts teammate Steve Genter who refused to take the silver medal that he felt belonged to DeMont