Memories of Moscow 1980: Medley Relay Thunder From Down Under Spoils Swim Spring For Soviet Men

Memories of the Moscow 1980 Olympic Games, where the Australian men’s medley relay overturned the form guide to snatch gold from Soviet hands after 17-year-old Neil Brooks entered the water on freestyle 0.81sec behind Sergei Kopliakov. Swimming World continues its 40th anniversary coverage of the events of Moscow 1980 and their impact on those who missed out and what the Moscow Games meant for those who made it, even, in some cases, when their Governments did not endorse their participation but their nations did.

Moscow 1980

Our Moscow 1980 Olympics coverage so far

- Memories of Moscow 1980: Craig Beardsley Belonged at the Games; He Belongs in the Hall of Fame, Too

- Memories of Moscow 1980: The Highs & Lows Of Living An Olympic Dream You Should Never Give Up On – By Glen Christiansen

- The Michelle Ford Story, Part One: The Phone Call From Her Mum That Changed Michelle’s Life Forever

- The Michelle Ford Story, Part Two: The Plan That Sank The GDR Machine And Hate Mail On The Biggest Day Of A Swimming Life

- Memories of Moscow 1980: Why Rica Reinisch Had To Retire At 15 After 3 Olympic Golds & 4 World Records

- Memories of Moscow 1980: When Sweden’s Pär Arvidsson Led A Podium Of Historic Firsts Over 100m Butterfly

- Memories of Moscow 1980: 40 Years On, Mary T. Meagher Shares Memories of Olympic Boycott

- Memories of Moscow 1980: 40 Years To The Day Since Vladimir Salnikov Cracked 15-minute Barrier Over 1500m Free

- Memories Of Moscow 1980: How Duncan Goodhew Converted Olympic Gold To Victory In Life

- Memories of Moscow 1980: When Barbara Krause Took 100 Free Below 55sec 20 Years Before Her Day In Court With Kipke

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – When Sergei Fesenko Became The First Soviet Swimmer Among Men To Claim Olympic Gold

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – 40 Years Since Boycott Buried The Chances Of Cheryl Gibson & Maple Mates

- Moscow Olympic Flagbearers Max Metzker And Denise Boyd Linked Forever In Australia’s Proud Olympic History

- USOPC CEO Sarah Hirshland to 1980 Olympic Team: ‘You Deserved Better’

- The Moscow Boycott: A Toxic Mix of Sports and Politics Proved Costly for Hard-Working Athletes

The Medley Relay Mash In Moscow

In the absence of the United States, West Germany and Canada due to boycott, the form guide for the 4x100m medley looked set to be a battle between hosts, the USSR, and Sweden, with Australia, Britain, East Germany, France and Hungary all with a shot at the medals.

The Swedes were having a fantastic week: Bengt Baron had claimed the 100m backstroke crown; Per Arvidsson had triumphed in the 100m butterfly and Per Holmertz, despite a foot injury sustained on pre-Games camp, had taken silver behind East German Jorg Woithe in the 100m freestyle. Add in Glen Christiansen, Swedish champion with a best within half a second of what it took to win gold in the solo event he did not race in and Russia understood well that it had its work cut out.

The Swedes took the same tactic as the Russians: the best quartet would be saved for the final. The Australians raced their best team in heats barring one spot, Glen Patching, on backstroke, to be replaced by Mark Kerry in the final and backstroke specialist Mark Tonelli called on to give it his best shot on butterfly.

In the heats, the teenager racing breaststroke for Sweden left his blocks a touch too early: the best quartet would rest through the final, too, the drop of that moment eloquently told by Christiansen in a first-person piece here at Swimming World today.

The Russians had it – but someone forgot to tell the Aussies.

Viktor Kuznetsov, back in the Soviet fold after serving a doping ban, set the pace on backstroke, his 56.81 granting the hosts a lead of a second over 20-year-old Kerry – who was born in Woollongong but spoke with an American twang after having studied theatre and drama at Indiana University for four years – on 57.89.

Peter Evans recovered good ground on breaststroke for Australia, his 1:03.01 split putting the Soviet team on notice as Arsens Miskarov clocked 1:03.64. Little in it: 2:00.45 to 2:00.90.

Yevgeny Seredin powered ahead of Tonelli down the first lap of ‘fly but the Australia refused to let go and on the way home, 54.58 for the Soviet swimmer and 54.94 for the backstroke specialist leaving Sergei Kopliakov with a 0.81sec advantage over Neil Brooks going into freestyle.

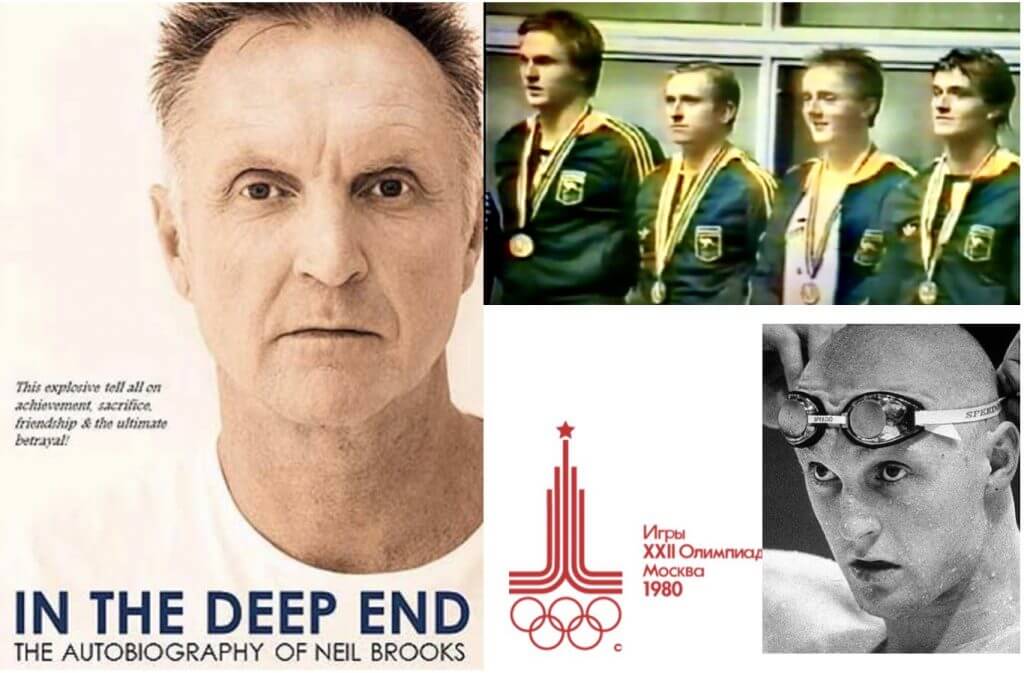

Neil Brooks, Peter Evans, Mark Tonelli and Mark Kerry of Australia on the podium at Moscow 1980 – Photo Courtesy: YouTube

Brooks rocketed from his blocks and within the first 20 metres had drawn level and over the 30m or so to the turn edged into the lead, sending Aussie commentators into a frenzy (video below).

“The Big Bloke” (6ft 6) born in Crewe, England, and known as Brooksy, was a few days shy of his 18th birthday when he rolled into his turn a tiny touch too sooner, his legs a “long” on the wall, the drive off which was not as powerful as that of Kopliakov.

The Soviet swimmer had a fractional edge on the Australian as the two men set off for the most important home lengths of their lives as far as team pride was concerned. Within 10m it was clear that Brooks had what might be called the sheer-guts dig, drive and ride-the-wave edge on his rival: he bounced himself into a slight lead that only someone pulling a giant plug on the whole pool was going to make him give up, it seemed.

In 3:45.70, it was gold for Australia, the USSR 0.22sec behind, Britain taking the battle for bronze, with Gary Abraham on backstroke, 100m champion Duncan Goodhew on breaststroke, David Lowe on butterfly and Martin Smith, who was born in the same northern town as this author, on freestyle. The late Paul Marshall had raced on backstroke in heats and remains the closest Britain has ever had to a black swimmer making the Olympic podium in the pool: in 1980 prelims swimmers did not receive relay medals despite the role they played in qualifying the quartet for the final.

The winning medley relay time that day 40 years ago did not get close to the 3:43.22 in which John Naber, John Hencken, Matt Vogel and Jim Montgomery had lifted the medley relay crow four years earlier at Montreal 1976. At World championships in Guayaquil in 1982, the Americans took the pace of pioneering down to 3:40.84 courtesy of Rick Carey, Steve Lundquist, Matt Gribble and Rowdy Gaines, for whom Moscow 1980 had been called off by order of the White House.

Among the others teams were World record holders and Olympic, World and European champions in their day, such as Woithe, Roger Pytell, of the GDR, Sandor Wladar and Zoltán Verraszto (father of current medley ace David and his world-class sister Evelyn), who finished first and second in the 200m backstroke in Moscow.

On the day, The New York Times wrote that Australia, “led off by Mark Kerry, a 20-year-old who trains at the University of Southern California, upset the favored Soviet team, spoiling what had been expected to be the evening Soviet men crowned their emergence as world-class swimmers”.

That did reflect the fact that until Moscow, no Soviet man had ever claimed Olympic gold in the pool but after Sergei Fesenko opened a new chapter with victory in the 200m butterfly, four others, including Vladimir Salnikov, piled in with their own victories for the hosts of the 22nd games.

There weren’t many Australians in the crowd that day, given the circumstances of boycott but as The New York Times noted:

“A small but vocal band of supporters, furiously waving Australian flags from the stands, cheered them on, and they responded together in the pool after it was over, with victory signs.”

Aussie Medley Relay Gold

In The Deep End – Brooks On His Days As A Member of the Mean Machine

Four years after Moscow 1980 and medley relay victory, Neil Brooks would get to feel like his Soviet rivals felt in Moscow: in the 4x100m freestyle relay at Cons Angeles, Americans Chris Cavanaugh, Michael Heath, a young Matt Biondi and Rowdy Gaines (with Tom Jager and Robin Leamy racing in heats) kept the Australians at bay 3:19.03 (WR) to 3:19.68. The Australian quartet of Greg Fasala, Brooks, Michael Delany and Mark Stockwell (the latter later to marry Tracy Caulkins), were known as “The Mean Machine”.

In 2013, on publication of his autobiography, In the Deep End, Brooks claimed that he claimed bronze with mates in the medley relay at the Los Angeles Games with “the worst hangover in the history of mankind”.

Brooks raced to 4x100m free silver on August 2. That was supposed to have been his last swim – so he went for “a few beers” on the outskirts of the Olympic village. In his autobiography, he recalls:

“We had one of the biggest celebration nights in history and never left the beer garden. I remember waking up on the grass at 7am with Justin Lemberg and one of the other guys standing over me. Justin said, ‘you’re swimming in an hour Brooksy’.”

Stockwell, silver medallist in the 100m free, had a dodgy shoulder and was being reset for the final of the 4x100m free on August 4 – and it was Brooks who had got the all to race in the heats.

Brooks said he had to be carried back to his accommodation and had coffee and breakfast poured into him. He swam the heat in 49.3 seconds, just two tenths slower than he had in the freestyle relay – in which Australia had won a silver medal – and helped the team qualify in second place for the final.

Born in England in 1962 to a 17-year-old single mother, Brooks was adopted by bricklayer dad Mick Brooks and his wife Nora at the age of six months and migrated to Perth in 1966. His autobiography is well worth a read. The West Australian described it as “a tale of tragedies in his life, the death of his adoptive mother, the failure of being unable to connect with his natural mother and the disastrous business dealings which eventually led him to flee Australia for Europe. Brooks, now aged 50, has been through more highs and lows than most others would in three lifetimes.”

Another DDR win in another final from 40 years ago

Women’s 100m Breaststroke – Athletes: 25; Nations: 19

- 1:10.22 Ute Geweniger GDR

- 1:10.41 Elvira Vasilkova URS

- 1:11.16 Susanne Nielsson DEN

1:11.48 Margaret Kelly GBR

1:11.72 Eva-Marie Hakansson SWE

1:12.11 Susannah Brownsdon GBR

1:12.21 Lina Kachushite URS

1:12.51 Monica Bonon ITA

On this day 40 years ago, the biggest name missing was that of Tracy Caulkins, the American mentioned above in the story of Australia’s medley relay. Three days after the 100m final in Moscow, Caulkins won the U.S. Outdoor National title in 1:10.40.

In Moscow, the fourth heat saw 16-year-old Ute Geweniger (GDR) shave 0.09sec off her own world record in 1:10.11. In the final, she turned in fifth but ploughed through the field on the way home for a 1:10.22 victory ahead of Elvira Vasilkova (URS) and Susanne Nielsson (DEN), with Margaret Kelly (GBR) locked out by a touch – and the stain of doping that skewed and scared women’s swimming for the best part of 20 years during the 70s and 80s.

In the early 1990s, confirmation of a secret state-run, systematic doping programme, State Plan 14:25, made clear that the vast majority of GDR results from 1973 until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 were fuelled by Oral Turinabol. Not a single result has ever been removed nor has any attempt at reconciliation been made so that the victims of the doping – both those who lost just rewards and lifelong status and those who paid a terrible price in terms of health and welfare, not just their own but also when it came to children born with severe disabilities – might be recognised in the context of the reality and truth of those years.

I don’t want these marvelous stories to end!