Making Failure Your Friend: The Irony of Chasing Your Dreams

By Melissa Wolf, Swimming World College Intern.

Even Olympic gold medalists have experienced failure. Don’t let missing your goal by three one-hundredths of a second cause you to quit; failure is part of the process and can be used as motivation to find your true potential and biggest strengths.

This past month as the 2020 U.S. Olympic Trials, times were released; coaches and swimmers all over the country sat down to write new goals to finalize their plans and start the countdown. Young swimmers who were spectators at the previous meet in Omaha are hoping to be competitors this time around. William Hayon, age 14, of Wisconsin says: “When I was 12 watching the Olympic Trials on TV, I thought that I would never get an Olympic Trial cut. Now, two years later, I am only two seconds away from some events and now know my dream is within reach.”

Over the past months, coaches and swimmers alike have spent nights dreaming of the day they will have earned their trip to be on the biggest stage in USA Swimming. But have they also prepared for what could be the hardest part of their success: failure?

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

As teams plan and prepare for the next 600 days of training and competition, it would serve them well to remember the quote from billionaire Arianna Huffington: “Failure is not the opposite of success. It is part of success.” As meets come and go over the next year and a half, some swimmers will be added to the list of qualifiers while others will continue the process of improving to try again. There are many stories of great swimmers whose passion for the sport did not end when there was a perceived failure but instead led them to greater success.

At the 1996 Olympic Trials, Misty Hyman-Hovey failed to make the U.S. Olympic team after placing third and fourth in the 100 and 200 meter butterfly events. She missed making the Olympic team by only three one-hundredths of a second. Hyman-Hovey shares her thoughts on these races:

I have found it’s usually our most difficult challenges that help us find our biggest strengths. The 1996 Trials gave me perspective that carried me through to 2000. I learned that even though my dream was to be in the Olympics and win gold, that wasn’t why I went to the pool everyday. I realized that I went to the pool because I love it. And as long as I was loving the process of becoming the best I could be, then no matter what the final outcome, I had won.

Then at the 2000 Olympics, she did what was thought to be impossible: she not only won gold but also beat Susie O’Neill, who was undefeated for six years in the 200m butterfly. Thankfully, Hyman-Hovey’s failure to make the team in 1996 did not end her swimming career, because she found her biggest strengths in her passion and love for swimming and sharing it with others.

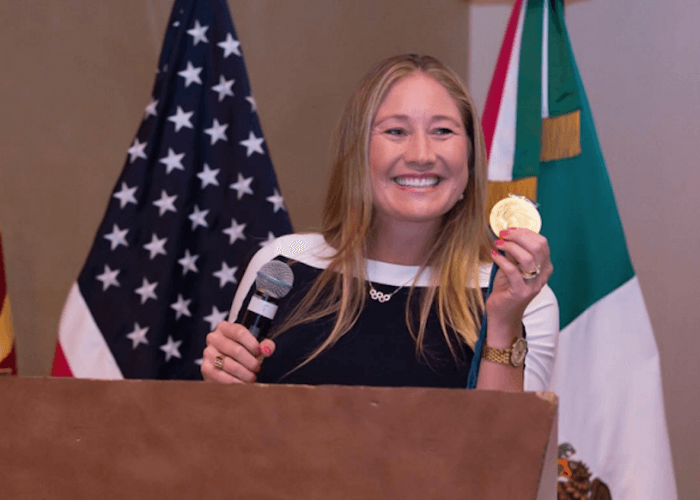

Photo Courtesy: Misty Hyman @mistyfly23

For many swimmers young and old, qualifying for this meet is the goal. For a few others, making it to the meet is not good enough: they have their sights set on qualifying for a final or making the team. No matter where you are with your ambitions, there is a chance that you may put it all out there, share your goal with others, spend endless amounts of energy and time training and you fall short.

What you do with this outcome could be more important and life-changing than actually achieving your goal. Swimming has numerous universal and unifying factors – failure is one of them. Every swimmer fails; even the Austrailian who was undefeated for six years in one event failed to keep her crown when racing someone who embraced a previous failure and found her love for the process.

Another young swimmer from Wisconsin, Malia Francis, shares her experience with how learning to fail in training helps her compete:

I’ve been training USRPT for the last four years. Failing became a part of practice. Doing these USRPT sets daily taught me that falling short of your goal is okay. It has also shown me the huge difference between mental and physical fails. Over the years of training this way, I’ve learned from my failed races in meets, and instead of letting them affect me negatively, I can allow them to motivate me to keep working towards my goals of the Olympic Trials.

Photo Courtesy: Malia Francis

Let’s become experts at failing – failing with a purpose to make ourselves better. To become experts at something, we need to practice it. Rarely do we practice failing, even though it is a part of life in every arena. While balancing positive self-talk and motivation with practicing failure, coaches can help their athletes become resilient so that disappointment can run off their back without leaving a mark. Swimmers will be able to approach their next event or set at practice with the mindset that failure is a normal part of the process, not the end of it.

May we learn from Hyman-Hovey and others to let our failures drive us to try again – not drive us to quit. At the pool during a hard set with your team by your side, practice failing. Set your goals high, and if you miss them by three one-hundredths or by two seconds, take a deep breath and try again. There is always another chance in swimming, even if it is four years away.

All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine not its staff.

Best Olympic moment EVER?