League Of Olympic Swim Legends: Mike Barrowman Tops 200m Breaststroke Podium With Kitajima & Wilkie

What would have unfolded had Tokyo 2020 gone ahead as planned this week – and where would it all have fit in the thread of Olympic swim legends and pioneers like Mike Barrowman, Kosuke Kitajima and David Wilkie? To mark the eight days over which the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games would have unfolded had the coronavirus pandemic not forced postponement, the team at Swimming World is filling the void with a Virtual Vision Form Guide and League of Olympic Swimming Legends.

Day 5, event 2 – Time-warp treasures on the Olympic Trail …

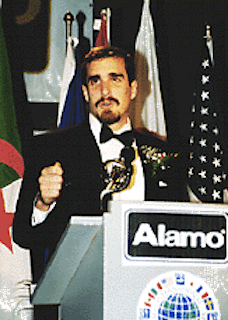

Mike Barrowman – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

Men’s 200m Breaststroke

The Podium

- Mike Barrowman (USA)

- Kosuke Kitajima (JPN)

- David Wilkie (GBR)

The Other Finalists (Listed Alphabetically):

- Victor Davis (CAN)

- Daniel Gyurta (HUN)

- John Hencken (USA)

- Yoshiyuki Tsuruta (JPN)

- Joe Verdeur (USA)

- Our Lane 9* place goes to an Australian winner of the 200m title, a 17-year-old 1964 champion who defeated the World-record holder Chet Jastermski (USA) by establishing a new pioneering pace:

- Ian O’Brien (AUS)

* – in our series, we will use Lane 9 to add an athlete whose story reflects extraordinary situations of different kinds, including being deprived by those who fell foul of anti-doping rules or by political decisions or, indeed the Olympic program, as well as simple facts such as “he/she was the only other title winner who claimed gold in a WR but didn’t make out top 8 on points”

All-Time Battle Of Olympic Swim Legends Goes To Mike Barrowman

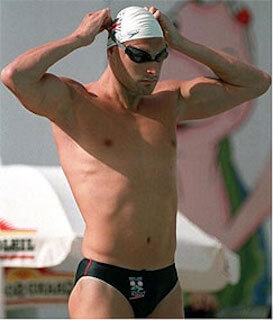

Kosuke Kitajima – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

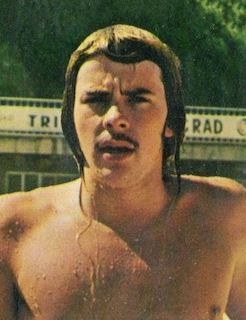

David Wilkie

Ahead of his time, the proof in a 13-year reign as the world-record holder, the United States’ Mike Barrowman left the competition battling in a secondary race during the peak years of his career. Pushing the wave-style breaststroke to prominence, Barrowman set six world records during his career and clipped Japan’s Kosuke Kitajima for the Legends gold medal.

The world champion in the 200 breaststroke in 1991, Barrowman traveled to the 1992 Olympic Games as the heavy favorite for gold. The American more than met the expectations thrust upon him when he covered his four laps in 2:10.16 to win by more than a second. Having set his first world record in 1989, Barrowman’s last endured until 2002, when Kitajima became the first man under 2:10.

Kitajima set three world records during his career, but it is his status as a double Olympic champion (2004/2008) that delivers him the silver medal behind Barrowman. Coupled with his pair of Olympic titles in the 100 breaststroke, Kitajima stands out as the premier overall breaststroker in history, his speed and endurance equally impressive.

The race for the bronze medal came down to Great Britain’s David Wilkie and American John Hencken, rivals in the 1970s. Each won gold and silver in the 200 breaststroke during their Olympic appearances, but it was Wilkie’s pioneering swim of 2:15.11 at the 1976 Games in Montreal – which chopped three seconds off the previous world record – that landed him on the Legends podium.

The Hungarian Breaststroke Used By Mike Barrowman:

When Mike Barrowman Set A Pace Of Victory That Would Not Be Topped Until Three Olympics Hence

1992 Barcelona – Men 200m Breaststroke: Athletes: 54 Nations: 41

- 2:10.16wr Mike Barrowman USA

- 2:11.23 Norbert Rosza HUN

- 2:11.29 Nick Gillingham GBR

2:13.29 Sergio Lopez ESP

2:13.32 Karoly Guttler HUN

2:13.59 Phil Rogers AUS

2:14.70 Kenji Watanabe JPN

2:15.11 Akira Hayashi JPN

Date of final: July 29, 1992

Nick Gillingham, who made what remained the fastest 200m podium in world swimming until 2001 and in Olympic waters until 2004.

At the 1988 Games in Seoul, when Jozsef Szabo (HUN) won the 200m crown, Mike Barrowman (USA) was edged out of the medals by 0.24sec. That fourth place was the best thing that had happened to the American in terms of fuelling his ambition.

Just over 10 months later, on August 4, 1989, five years and two days after Victor Davis’s 1984 Olympic triumph and in the same lane 5 at the Los Angeles UCLA pool, the American broke the Canadian’s world record in 2:12.90 at US Nationals on his way to the 1992 Olympic title via six world records which were interrupted only by Nick Gillingham (GBR), who equalled the 2:12.90 mark to claim the first of three European titles in Bonn on August 19, 1989. A day later, at the Pan-Pacific Championships in Tokyo, Barrowman claimed the record back for himself in 2:12.89.

In January 1991, Barrowman claimed the world title in Perth, Australia, in a world record of 2:11.23 and then clocked 2:10.60 at Fort Lauderdale in August 1991. At trials the following year, however, the pioneer pace-setter was beaten by Roque Santos, and, just days before the Games he had been rocked by the sudden death of his father.

At the Games in Barcelona, after watching rivals Norbert Rozsa (HUN) and two of the 1988 medallists ahead of him, Gillingham and Sergio Lopez (ESP), cruise through – and also witnessing the elimination of Santos – Barrowman rose to his blocks in the seventh heat. Four lengths later, he held the Olympic record in 2:11.48, 0.14sec faster than any other man had ever swum, the European record and second-best all-time held by Gillingham at 2:11.62.

Later that day, the Barcelona Olympic Games witnessed a world record that would stand for more than 10 years, one achieved in what would remain the fastest Olympic podium until the Athens 2004 Games.

Barrowman set the lead pace all the way to gold, via splits of 30.43, 1:03.91 and 1:37.12, the last turn leaving him 0.13sec outside his own world-record pace. All the while, Gillingham and Rozsa shadowed the American World champion: the biggest range between the three at any one point was 0.75sec, which was the gap between Barrowman and Rozsa at the last turn. The American produced a sensational 33.04 split on the way home to crush his World record for a 2:10.16 victory. Behind him in 2:11.23, a European record, Rozsa edged out Gillingham (2:11.29) for the silver. Nine years would pass before any race would produce a faster podium: at the 2001 World Championships, Brendan Hansen clocked 2:10.69 four victory ahead of 2:11s from Austrian Maxin Podoprigora and Japan’s Kosuke Kitajima at the start of a new and long rivalry between the winner and the third man home that day.

Barrowman’s record lasted until Kitajima became the first sub-2:10 swimmer, on 2:09. 97, on October 2, 2002.

Born in Paraguay, Barrowman celebrated a sixth World record in Barcelona. Only Joe Verdeur (USA), the 1948 champion who swam with butterfly arms, had ever held as many records over 200m. Taught to swim by his grandmother, a Red Cross instructor, Barrowman was coached by Hungarian Jozsef Nagy at the then Curl-Burke* program. Nagy developed the “wave-action” breaststroke, which mimicked the head-over-rolling-shoulder movement of a cheetah running.

When he returned home from Barcelona, Barrowman’s neighbours in Potomac, Maryland, had painted his lawn gold.

After retiring from the pool, Barrowman finished 15th at the 1996 US Olympic Trials for kayaking.

* – the program was later renamed after coach Rick Curl’s exposure and fall from grace as a sexual abuser who was sent to jail for seven years.

Other Great Olympic Battles over 200m breaststroke:

Kosuke Kitajima in the depths of the Pantheon with his four Olympic golds – Photo Courtesy: Junya Nishigawa, Olympus Digital

2004 Athens – Men 200m Breaststroke – Athletes: 47 Nations: 38

- 2:09.44or Kosuke Kitajima JPN

- 2:10.80 Daniel Gyurta HUN

- 2:10.87 Brendan Hansen USA

2:11.20 Paolo Bossini ITA

2:11.76 Vladislav Polyakov KAZ

2:11.94 Michael Brown CAN

2:11.95 Scott Usher USA

DQ Jim Piper AUS

Date of final: August 18, 2004

Kosuke Kitajima (JPN), born September 22, 1982 in Tokyo, stood just 1.77m tall and weighed in at 71kg. He was big in the water though: at Barcelona in 2003, he won the 100m and 200m world titles in world records of 59.78 and 2:09.42 ahead of Brendan Hansen (USA). Kitajima had given warning at the World University Games in Busan in 2002, when he became the first man to race inside 2:10 in the 200m breaking American Olympic champion Mike Barrowman’s 1992 standard of 2:10.16 with a 2:09.97 victory.

In July, 2004, at US Olympic trials in Long Beach, Hansen rattled the world of breaststroke with world records of 59.30 and 2:09.04. The stage was set for a showdown in Athens. The mood was particularly tense because of events surrounding Kitajima’s style.

He provoked a protest at the World Championships in Barcelona, 2003: Americans claimed that he was using a butterfly action underwater out of turns. These protests were lodged again at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. Video footage clearly shows that Kitajima used one decisive dolphin kick off every wall. At the time, FINA Rule SW 7.5 stated:

“A scissors, flutter or downward dolphin kick is not permitted. Breaking the surface of the water with the feet is allowed unless followed by a downward dolphin kick.”

As this slo-mo of the turn in the Olympic final at Athens 2004 shows, Kitajima did execute one, clear downward dolphin kick, three things important to note:

- turbulence at the surface can negate the rule as far as the deck judge is concerned because what can be seen underwater cannot be seen from above;

- video footage was inadmissible in protests;

- there are many incidents in competition on big occasions and when World records have been established and ratified and results allowed to stand even though prevailing rules were clearly broken, breaststroke a particular problem because of the inability of judges to see past splash to what the video does in fact reveal but has been discounted as evidence.

Two days after winning the 100m crown and leaping out of the water to issue a primordial scream of “Cho-kimochi-ii” (“I feel mega-good”), Kitajima cruised through to the final of the 200m behind Daniel Gyurta (HUN), aged 15 years, 3 months and 13 days, who was fastest in heats and semis on 2:11.29 and 2:10.75.

In the final, Kitajima led from start to finish, turning at the 50m mark in 29.10 – 0.30sec up on Hansen, with Gyurta back in seventh on 30.40 – at 100m in 1:02.12 (Hansen, 1:02.39, Gyurta, 1:04.06) and at 150m in 1:35.96, to Hansen’s 1:36.08. Down that third length, Gyurta had swum 32.82 and was now just 0.8sec behind the American. Kitajima pushed on with a last split of 33.48, for victory in 2:09.44, an Olympic record that eclipsed Barrowman’s 1992 standard.

Gyurta split a last length of 33.92, to a 34.79 for a tiring Hansen. That left the 15-year-old with silver by 0.07sec and kept at bay the fast-finishing Paolo Bossini, on 2:11.20. Gyurta’s achievement made the Hungarian the second-youngest male swimmer ever to make an Olympic podium, after the 15 years and 57 days of the 1932 champion in the 1,500m freestyle, Kusuo Kitamura (JPN).

The frustration that had bottled up in Kitajima because of the American protests over his style spilled over on the poolside after the 200m final, when he declared:

“That talk about the kick just motivated me all the more to stick it to them. They can stop talking now.”

Even so, Kitajima did indeed use a downward dolphin kick. He was never once disqualified but the debate that ensued led to the FINA Technical Swimming Committee changing the rule: one dolphin kick out of breaststroke starts and turns would subsequently be allowed.

In 2005, Kitajima lost both his world titles to Hansen, who in 2006 left the world records at 59.13 and 2:08.50.

When David Wilkie Clocked A Time Good Enough For Gold, Silver & Bronze At The Next Three Olympics After He Retired

David Wilkie

1976 Montreal – Men 200m Breaststroke – Athletes: 26 Nations: 18

- 2:15.11wr David Wilkie GBR

- 2:17.26 John Hencken USA

- 2:19.20 Richard Colella USA

2:19.42 Graham Smith CAN

2:20.79 Charles Keating USA

2:21.87 Arvydas Juozaitis URS

2:22.21 Nikolai Pankin URS

2:22.36 Walter Kusch FRG

Date of final: July 24, 1976

In between the 1972 and 1976 Olympic Games, the rivalry between David Wilkie and John Hencken drove breaststroke standards well into uncharted waters. Wilkie won the 1973 world title in the 200m in a world record, the 1975 world titles in the 100 and 200m, while Hencken won the 1973 world title in the 100m, finished second to Wilkie in the 200m, missed the 1975 World Championships and, along the way, set four world records in the 100m and three in the 200m.

In Montreal, four days after Hencken had claimed the 100m crown a touch ahead of Wilkie, the American looked like a strong candidate to join an elite club: only one man in history had retained an Olympic breaststroke title: Yoshiyuki Tsuruta (1928-1932, 200m). Could Hencken be next?

The world-record book favoured him, Hencken having swam 1.07sec inside Wilkie’s 1973 global standard in two stages in 1974 to leave the mark at 2:18.21. In the first heat, Rick Collela, fourth in 1972 when Hencken beat Wilkie and Nobutaka Taguchi for the crown, set the pace with an Olympic record of 2:21.08. In the fourth heat, the Scot showed that he meant business with a 2:18.29 that woke the crowd up.

In the final, Hencken went out hard, inside world-record pace at 100m, on 1:06.09, with Wilkie hanging on his shoulder, on 1:06.49. The Scot had inched ahead at the final turn but at that point nothing had been decided, at least beyond the mind of Wilkie and those who knew the athlete best, coaches Dave Haller in Britain and Bill Diaz in the United States. Out of the turn, Wilkie began to open up what would become a yawning gap between him, Hencken and the rest of the field that was falling further behind with every stroke.

Wilkie’s homecoming split, 1:08.62, was phenomenal, a time that would have placed him just outside the medals in the straight 100m final just two Games before. It gave him an end time of 2:15.11, one of the most magnificent performances in Olympic swimming history, one that prevented a sensational USA men’s team from winning every gold medal in the pool in 1976, one that made the Scot the first British man to win an Olympic crown since Henry Taylor lifted the 400m and 1500m titles and joined teammates for 4x200m free goldin 1908.

Hencken looked up at the scoreboard to confirm a feeling that he had raced better than ever: he had cracked his own world record by 0.95sec, to finish on 2:17.26. But he had lost the crown by 2.15sec. Colella gained consolation for his fourth place in 1972 by stepping up to the bronze as the third man to break the 2:20 mark, in 2:19.20, with Graham Smith the fourth to get inside that barrier, in 2:19.42.

Wilkie’s world record, 3.1sec inside Hencken’s previous best, would survive six years and the time would still have won a medal three Games later, in 1988, and placed him in the 1996 final 20 years after his finest sporting moment. Born in Ceylon (later Sri Lanka), Wilkie went on to develop a successful green health and cosmetics company.