Jorge Machicote, Puerto Rican and Pitt Water Polo Player: Not a Fighter But I Will Drown You in the Pool

Editor’s Note: In one of the seminal matches in Eastern water polo history, on November 13, 1977, Pittsburgh faced Bucknell at the Joseph C. Trees Pool for the Eastern Water Polo League Southern Division Championship. A rematch of the 1976 final, won 14-12 by Pitt, with less than a minute remaining the host Panthers held a two-goal lead and appeared headed to another NCAA men’s tournament as the East’s best team. But, in a memorable turn of events, the Bison rallied to force overtime, and won the game 21-20 on a shot by Mark Gensheimer in the first minute of sudden death.

Following is the second in a series of articles about the participants involved in one the more memorable polo matches in Eastern intercollegiate history. The first is an interview with Scott Schulte, who played for Bucknell in that fateful game. The third is a conversation with Jay Fisette, Schulte’s teammate on the 1977 Bucknell squad. The fourth is an interview with Miguel Rivera, architect of the Pitt men’s water polo program.

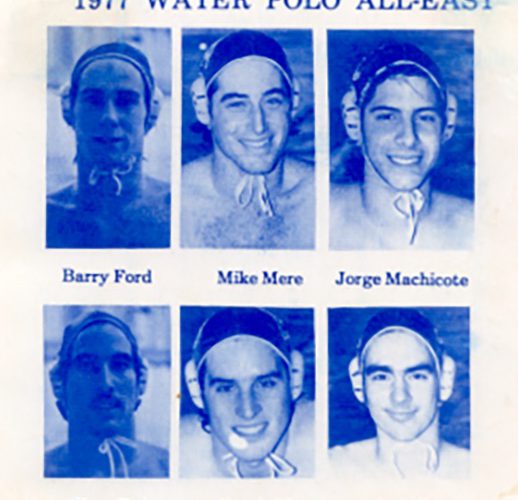

It’s the classic immigrant story; young man comes to America on an athletic scholarship, establishes strong connections through education and sports, then enjoys a successful career in business. In many ways, this describes Jorge Machicote’s experience. He played water polo for Pittsburgh in the 1970s, during a formative era of Eastern polo, then moved on to a successful career with Banco de Ponce.

But “Machi”—as he’s affectionately known in the Puerto Rican polo community—enjoyed his most satisfying accomplishments representing his country in international play. A long-time polo athlete who first donned a speedo as a ten-year-old competing for the Casino de Puerto Rico club, Machicote grew up playing for the national team as a member of the island’s greatest polo generation. Teammates included Rafael and Carlos Gonzalez, Manfredo Lespier and Carlos “Kaki” Steffens, father of Olympians Jessica and Maggie Steffens.

Speaking with Swimming World from San Juan, where he has lived since 1988, Machicote described the challenges—and benefits—of playing under coach Fernando Salabarría, the involvement of Americans like Lee Walton in growing the sport on the island, where the sport in Puerto Rico is at the moment—and the legendary polo contest in 1977 between Pitt and Bucknell that determined the East’s best squad.

– Visits by teams from outside the island, in particular from the United States, spurred the development of Puerto Rican water polo in the ‘70s.

It started when we were ten years old. The first time I saw water polo was when I was an age group swimmer at the Central American Games [in San Juan]. I started swimming, just like Carlos [Steffens] in the same club. The water polo games were held in the same pool as the diving competition.

Jorge Machicote. Photo Courtesy: J. Machicote

During Christmas in 1970 or ’71, that’s when the national tournament in Puerto Rico was held. In those days, they invited teams from the States. But it was not only the NYAC—which was the best team in those days.

After we saw Cuba and Mexico in the Central American Games, our coach—Fernando Salabarría—he started a water polo team. Frankly, I hate swimming! Everybody who swam for the club, which was named Casino de Puerto Rico, tried out for water polo.

We only had two teams—one senior [players] and us, 12 and under. When we practice—even though we were very young—we practiced with the older guys because there was no way to play with anyone else. The seniors were the ones who started water polo—like Carlos Gonzales [and] Miguel Rivera. We didn’t have any one to scrimmage or play. To our advantage, we were able to start playing and practicing with the seniors.

Our coach was very demanding, and the intensity that he put in the practices was creative. You always had to do something and do it well. Just to give you an idea, our club was right next to the beach. He wanted us to run in the water up to our knees to use our legs a lot. We didn’t have any weights, so he would fill soda cracker containers with cement and put a tube in the middle.

That’s how we started water polo here. It was primitive and creative but that’s why in our first year—the Central American age group are every two years. In 1971, was the first time there was water polo age group for Puerto Rico. Carlos was on the team also, and we went to Cuba.

In 1973 we went to Colombia, and in 1975 we went twice to Mexico; in ’75 the Central American Games were in Mexico and, two months later, the Pan American Games [were held there]. This is why this generation of the ‘70s was very good. We got international experience—and it was just before we graduated from high school. I graduated in 1976.

Carlos and Rafael Gonzales were already in California. When Carlos and myself were juniors, they tried to transfer us to California. But our parents wouldn’t let—either Kaki’s or Machi’s parents would let them go! We had the opportunity to attend Fremont High School—the coach [John Smith] came to Puerto Rico and said: I want you, and you and you.

Piscina Olimpica del Escambron. Photo Courtesy: J. Machicote

In 1975, when we were 16 years old—Manfredo [Lespier], Kaki, myself, Raffi, Carlos—they selected us to be on the national team.

Of course, I was on the bench but I was on the national team. In those games, the coach for USA was Pete Cutino. That’s where Carlos got noticed from his coach from the United States, and that’s where he got recruited for Berkeley.

– How did the Puerto Rican team perform in the 1975 Pan American Games?

The coach was Fernando. In 1979, Lee Walton was the assistant coach with Fernando. But Walton knew us because Carlos Gonzalez used to play for him in San Diego State. He knew about the Puerto Rican water polo team and came down here and gave clinics.

That team that went to Mexico in ’75 was very young. I was 16 years old. Carlos was 16, so was Manfredo. Raffi was 18—it was a very young team. All those teams we were playing in 1975, they had already been in Europe scrimmaging there.

For ’75 we spent April, May, June and July in California. We lived there for three months and a half. Practicing, working out and scrimmaging—going to tournaments. That’s how we got exposed to coaches in the States because they came to watch us. We were there before the Pan American Games.

I didn’t get any offer back then that I can remember. But Miguel Rivera knew that I was graduating. during the summer of ’76, he asked me if I wanted to go to Pittsburgh because he was forming a team. He invited me to an invitational in Pittsburgh and said: If you pay for your ticket, you’ll have room and board and transportation. I had my money so I did go to Pittsburgh. He took me all around and took me to the financial aid office. I was able to get a full-ride scholarship—everything included, except the transportation from Puerto Rico.

I was also accepted at Villanova, but they only had a swim team—and I told you what I think about swimming. There’s no way that I was going back to swimming.

The reasons I went to Pittsburgh was economic and there was a lot of recruiting coming from Puerto Rico then. Also, I went to a private Catholic high school, and 80% of my class when to the States to study. Of those [students] about 60% went to the East Coast.

– Your plan was always to matriculate at an American university.

Definitely. I wasn’t going to stay here, and it paid off. For 23 years I was in the banking industry, right out of college. I started in the international department—and everyone wants to go there!—because of my English.

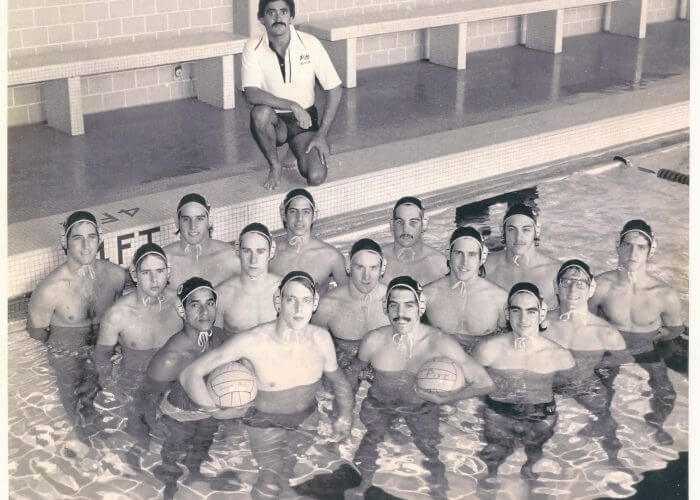

1977 University of Pittsburgh men’s water polo team. Photo Courtesy: Miguel Rivera

When I got [to Pittsburgh], the starting seven of the team, six were Spanish-speaking, and the goalie [Walt Young] was the only one who didn’t speak Spanish. When I got there, a referee, Paul Barren, was there. I remember him from the Central American Games age group play. He was an excellent referee and he knew that we come from a dirty game because in those days we were very physical. That was because of the international exposure we had before we went to college.

In the beginning a couple of times he would tell us: You know that I’m going to referee many games on the East Coast, and I know how you play. So, don’t be rude. Sometimes, I know that he didn’t see it but he’d do a kickout because he knew that we were very sneaky and physical.

Our first year [1976] we won the East Coast and then we went to the ’77 tournament, and we got to the game with Bucknell. That game it was 50/50, fans from Bucknell and from Pittsburgh. They even brought a radio broadcast with them.

– Your memory of this game is as important as any.

It’s like watching a very intense movie! That’s the only game that I’ve ever played to sudden death. It was the first and the last one. From the [result] you could tell that they were scoring and we were scoring.

– What happened at the end of regulation when you were nursing a one-goal lead?

We got the ball and Miguel called for a timeout. In the timeout, Miguel said: They’re going to pressure us, so the goalie [Steve Feller] has to move away from the cage and pass the ball ahead as far as he can. One thing that we knew was coming is that they left a player without defense because we were offense.

Photo Courtesy: Papo Ruiz

The goalie was going to start and they put a defender on [him]. When the referee blew the whistle. [Feller] put the ball in the water and started swimming with it. By doing that, the defense was able to guard him. He got nervous and passed the ball to the defense. I don’t remember who got it or who scored—all I know is he got nervous. and instead of throwing the ball very far, or waiting to see if someone would get open, he started swimming with the ball.

And those were not the instructions. That cost us our championship.

The guy who was guarding the goalie, he started swimming towards the cage after [Feller] threw the ball to a defender. {That defender] threw a pass to that guy [in front of the cage] and he just put the ball inside the cage.

– Dr. Rivera told me that there was a suggestion that you should start the play with the ball—and that might have made a difference at this moment.

That makes sense because of what I told you—that they were going to put pressure on [our goalie]. The thing is the referee gave the ball to the goalie, and he started without thinking, instead of giving the ball to me to start the play. I don’t remember what was the situation that the goalie was the one to have the ball to start.

What Miguel told you makes sense, because he knew they were going to put pressure on the goalie.

– You not only lost the game but you also ended up losing your coach. How did that affect your team and your desire to stay in Pittsburgh.

It made a huge difference. If Miguel was there, he would have fought for all the good things that happened in Pittsburgh. We could have had at least one maybe two years more. But he wasn’t, so he could not defend the program.

That was too bad because I still had two more years in college. I was thinking of going to California—but I wasn’t going to risk my scholarship. Maybe they give you half scholarships—all those things very good teams [do]. You have to be very good and if you’re transferring you have to demonstrate you can play on the team, especially with [Cal coach] Cutino—or [at] Stanford Irvine.

I kept in shape swimming, lifting weights, gaining weight for the Pan American Games in 1979, because they would be in Puerto Rico.

– What was your feeling representing your country in the 1979 Pan American Games?

For everyone—including me—it was good because the games were going to be held in Puerto Rico. For the ’79 Games we were playing in the Olympic-size pool [the Escambrón Olympic Swimming Pool]. We got a really big crowd coming in, a lot of our family (members) who never got to see us play. It was televised.

Water polo at the 1979 Pan American Games

But, that team could have done a lot better. We tied for third with Canada and because of goal average they got the medal and we didn’t. The team that went to Mexico for the ’75 games, now [there were] six or seven of that team were on the team for the 79 games. We were the youngest generation of water polo players from the ‘70s.

We had a goalie that was living in California and was practicing with us. He was 6-9 and was pretty big for a goalie. And he had experience. He was with us all three months. Two or three months before the games, he asked for money; “If you don’t pay me I will not play in the Pan American Games.”

– I take it you didn’t do it.

No. we didn’t give him the money. That’s when the second goalie, Orlando Mendoza—rest in peace because he died quite a few years ago—he became the goalie. From a 6-9 goalie—and you know the reach of that person—probably to a 6-foot goalie, that’s a big difference. And the experience of that the [previous] goalie had, that was a lot more than the alternate goalie had.

That was dramatic because we lost our goalie.

– Was there a desire to stay in the United States?

I graduated from Pittsburgh in 1980 and I started working in the international department at Banco de Ponce. a year and half later, the head of the department they promote him to New York. I was young and single, and he asked me if I wanted to go to New York. He wanted to go with someone he could trust with this assignment.

I said yes.

Three months after I started, I got a call from Joey Ferraioli a senior swimmer and water polo player of the same age as Miguel Rivera, Joey at that time was playing for the NYAC; he asked me: Listen, why don’t get together. Come to the club and we’ll talk.

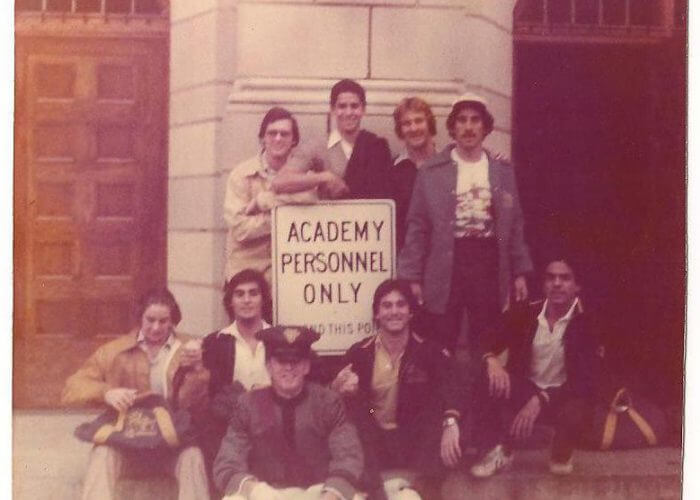

At West Point in 1977, Marchicote is center behind the sign. Photo Courtesy: Papo Ruiz

When I got to the club there were six guys from Bucknell, Chris Judge, another one from Brown—all these players I played against. It was a very warm reception. And they asked: Are you gonna play for us?

I decided to play because they not only offered me to play for them, they gave me free membership—just like a regular member. So I did play for the New York AC for about four years.

Everyone who played was a professional—doctors, lawyers. Joey was the legal counsel for Young & Rubican. He had a very important position back then.

Scotty [Schulte] was there. On the East Coast, back in college, it was me and Scotty; there were other players who were pretty good but we had the experience and he had the drive. In the beginning, I noticed that if I played defense on Scotty that would affect my offense because I’d get tired. And the same with him.

[On The Record with Scott Schulte, Bucknell, CWPA and USA Water Polo Hall of Famer]

We had some body—and it was a very good one!—to guard Scotty. And it was Butch Silva to take care of him. And [Bucknell] had [Mark] Gensheimer he used to guard me, so we could be more offensive in the game.

Pitt vs. Bucknell was just like Navy vs. Army or Penn State vs. Pitt. The same rivalry.

– In the 80’s, The Olympic Club was tops in masters’ water polo. Carlos Steffens played for them during this stretch. As a NYAC player did you face him during this stretch?

Many times. We didn’t guard each other. We could have, but it was a decision. Carlos was in excellent condition and he was better than me. Listen, I’m not going to guard you don’t guard me—unless we got stuck on a play with me.

Because of that relationship, I was very close with The Olympic Club. They invited me out for beers and I had to be very careful not to cross the line and not have anything against the AC. I knew these guys from college, and some of them were on the national team, so I knew them before. I knew the [U.S.] Olympic team from ’75 and ’79 from playing against them. Also, those summers from ’75 and ’79 when we spent two – three months in California.

I went to their parties—I even got invited to a wedding in California by Jim Purcell from Cal-Berkeley. He’s a great guy.

Water polo is like a fraternity. It doesn’t matter what country you play water polo—[people say] that we’re very cocky; I say: Why didn’t you play so you can belong to the fraternity? They know that water polo is a very physical game. No protection like in football.

I’m not a fighter outside [the pool] but in the water, I can drown you.

– You’ve traveled a lot because of your involvement with the sport.

When I came back [to Puerto Rico] in 1988, Fernando Salabarría was the coach for the junior national team and they did qualify to go to the junior world championship in France. He asked if I want to be his assistant coach. I traveled with the team to Barcelona for scrimmages and then we went to Narbonne. It was my first time to Europe.

I’ve been all over for water polo—to Central America as well as Mexico, Cuba, and all around the States with the New York Athletic Club.

– Puerto Rico has experienced such heartbreak of late. How does water polo come back in your country?

Funding. That was the problem. We don’t have our own federation, and Carlos has tried a lot to fix this. He said that he could not do anything more. He tried many things, even bringing [his daughters] Maggie and Jessica here to do free water polo clinics for kids. just to get a generation get interested.

In 2018 Maggie + Jessica Steffens offered free clinics in San Juan. Photo Courtesy: Maggie Steffens

Also, a lot of swimmers want to play water polo because they know how strong they will get. But they don’t last too long. You need the swimming background, like we had, but you need to understand it’s a physical game. You have to be like a football player and learn how to play with pain.

No pain, no gain.

The two main things: funding—we knew that to get better you have to go outside of Puerto Rico—to Europe and California to scrimmage there. We should have gone to Yugoslavia, Italy, Hungary, Spain, because there are many teams there, and the league is professional.

Finishing third [in 1979] we had a spot in the World Water Polo Championships. We didn’t have the funding—and didn’t get the exposure.

Machi is a real legend!!!!! Great guy from a great family. Remember him from age group swimming days at Casino de Puerto Rico!

Machi we miss you partner and it’s so great to hear the stories and remember the amazing times as a co.petiror and teammate.

Great article. So true water polo is sport for life.