Is 2:07 the New Standard in the Men’s 200 Breaststroke?

Later this week, Japan’s Shoma Sato could push the world record of 2:06.12 in the 200-meter breaststroke at the Japanese Olympic Trials. His presence in the event has certainly been felt and he is a leading contender for gold at this summer’s Olympic Games in Tokyo. He is also one of only five men to have gone under 2:07 in the event, with all of those athletes active. So, how did the bar in the 200 breaststroke get set so high?

All-Time Rankings:

- 2:06.12, Anton Chupkov, RUS, 2019

- 2:06.67, Ippei Watanabe, JPN, 2017

- 2:06.67, Matthew Wilson, AUS, 2019

- 2:06.74, Shoma Sato, JPN, 2021

- 2:06.85, Arno Kamminga, NED, 2020

Flash back to 10 and a half years ago in 2010, a year removed from the shiny-suit era of 2009 where swimsuit companies made a mockery of the record books by welding together polyurethane suits that were swifter than any suit before them. Japan’s Kosuke Kitajima led the world rankings with a 2:08.36, followed by Hungary’s Daniel Gyurta (2:08.95) and Australia’s Brenton Rickard (2:09.31). Flash forward two years and Gyurta was standing on the top of the Olympic podium with a 2:07.28 that had broken the world record from 2009 of 2:07.31. He was followed by Britain’s Michael Jamieson (2:07.43), who had been right on the old world record and Japan’s Ryo Tateishi (2:08.29).

Seven years after that, and a 2:07.2 was not even on the podium at the 2019 World Championships, where all three medalists were under 2:07 with Anton Chupkov breaking the world record with a 2:06.12. Following him was Australia’s Matthew Wilson in an impressive 2:06.68, right off his own world record the night before, and Japan’s Ippei Watanabe in a 2:06.73. Watanabe was the former world record holder and first man to break 2:07.

It took a 2:08.28 just to make the final in 2019, which led the world rankings in 2010 and was the fastest eighth place time every year this decade except for 2016 in Rio when it took a 2:08.20 to make the final.

How did the bar get raised so high? You have to analyze how differently Kitajima and Chupkov attack their races. Below are videos from the 2010 Pan Pacs and the 2017 Worlds (there is no full footage of the 200 breast final from the 2019 Worlds anywhere on the Internet for some reason).

Kitajima takes it out more aggressively on the front half and increases his tempo on the final 50, while Chupkov likes to stay long and strong on the first 150 and increases his tempo on the last length to almost a 100 tempo.

Using just a stopwatch, Kitajima’s tempo on the second and third 50 is around a 1.5/1.6 seconds per stroke, and he increases it to around a 1.4 rate on the last 50. Compare that to Chupkov, who lengthens his stroke to a 2.0 rate on the first 150, before switching to a 1.4 on the last 50 and eventually to a 1.1 rate in the last few strokes without slipping on the water.

Chupkov has a breaststroke unlike anyone in this generation. His ability to hold the water and keep his line is textbook breaststroke. Most swimmers have difficulty in holding their speed when stretching to a 2.0 rate, and most struggle with holding water when using a 1.1 rate, but Chupkov can switch to both with relative ease.

When asked how he can swim so effortlessly in breaststroke but still remain fast, Chupkov said after his world record at the 2019 Worlds:

“I can’t explain how I swim. It seems to me that I’m not doing something special, even in training and in competition as well. I just swim like I feel and actually I can’t explain it. Probably I was born into breaststroke.”

How Breaststroke Has Evolved

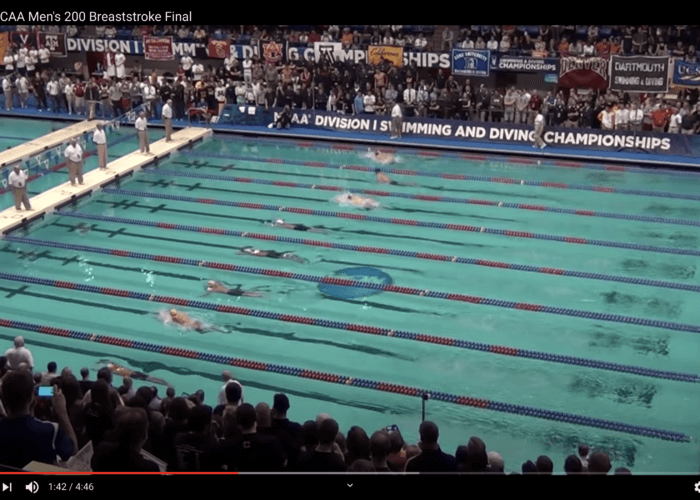

2013 NCAA final – the first stroke. Most of the finalists are not to the 15m mark. Photo Courtesy: John Charles screenshot

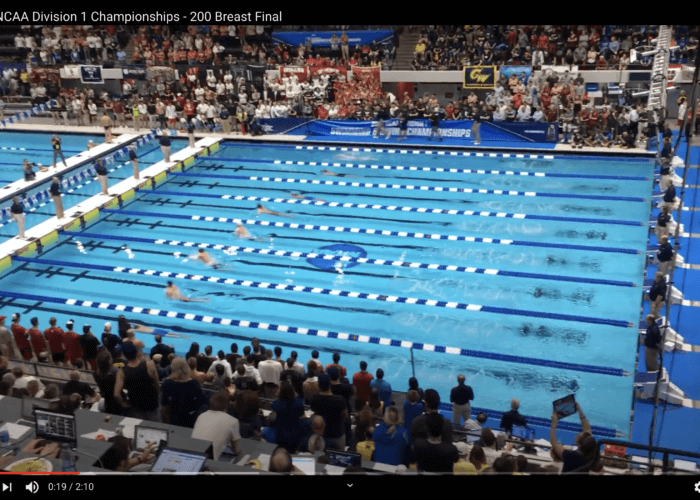

2017 NCAA final – the first stroke. Most of the finalists are past the 15m mark. Photo Courtesy: Triton Wear screenshot

The 200 breaststroke has become such a leg-driven event the last ten years. When Kevin Cordes swam a 1:48 in the 200-yard breast at the 2013 NCAAs, the big thing a lot of people took away from that race was how few strokes he had taken the entire race.

Swimming junkies were fascinated at how effortless the swim looked and that quickly became the new way to swim the 200 breast: swimming fast with the least amount of strokes.

Flash forward four years to the 2017 NCAAs, and nearly every single swimmer in the men’s A-Final had surfaced after 15 on their pullout, compared to 2013 when Cordes was the only one. Screenshots from each video from the same angle are provided to the left and right.

Coaches over the last few years have trained their breaststrokers to get the most out of their kick, while still swimming efficiently – utilizing the least amount of strokes in a 200 breaststroke.

And the time improvements have shown. In long course, 2:07 is the new standard to hit for men if you want to be considered world class. With Shoma Sato’s recent 2:06.8, it just proves that the bar has been raised. It may take under 2:08 to make the final in Tokyo, which not long ago would be on the podium. Now a 2:06 is required to be on the podium, and a 2:05 is within reach. The way the race is swam and how it has developed into more of a leg-drive event with more glide, has become the new normal in how to train for the 200 breast.

Chupkov’s ability to stay long and strong has caught the attention of the rest of the world, and his 2:06s have set the bar for others to follow. It is similar to how Adam Peaty’s 56 has caused others to believe that it is possible. When a new world standard has been reached, it inspires others to do the same, and breaststroke has reaped the benefits of this.

The stroke has become so athletic just in the last 15 years from when dolphin kicks were permitted on pullouts in 2005, and the times have dropped. 15 years ago, the world records in long course for men were 59.30 and 2:09.04, compared to 56.88 and 2:06.12 today, while on the women’s side they were at 1:06.20 and 2:21.72, compared to 1:04.13 and 2:19.11 today.

In 2005, dolphin kicks were permitted on pullouts, thus allowing breaststrokers to become better dolphin kickers with stronger cores. And the stronger core helped them hold their line while gliding, and therefore they needed to emphasize their kick in order to get max propulsion. All of those factors have led to where breaststroke is today: where a 2:07 is the new normal for men.

Hall of fame breaststroke coach Jozsef Nagy, who led József Szabó to Olympic gold in the 200 breaststroke in 1988 as well as Mike Barrowman to gold in the same event in 1992, wrote this about the future of breaststroke:

Arms, shoulders, and in general, the upper body, will have to be a lot stronger than it is now for a breaststroker. Also with all these physical characteristics/advantages, they should aim to have a better feel for the water within the various aspects of their pulls. In order to progress, they will have to do a stronger, faster, and more efficient pull. The original, good-old breaststroke kick does not offer much room for progress. Whereas the breaststroke pull still has a huge potential! Especially if the swimmers will now be able increase the frequency of their stroke rate. However, this increased frequency cannot be supported with the present kind of breaststroke kick. As I mentioned before, a smaller, faster kick will be necessary to support the more powerful and increased pull frequency.