Ian Thorpe, Part 3: Thorpedo, Thorpey, The Pelé of The Pool & Boy With The World At His Flippers For Feet (WR Video)

Ian Thorpe – Three World Records In As Many Days

In the last of three features celebrating the career of the legendary Australian freestyler 20 years after he cracked three World records in as many days at The Australian Olympic Trials on the way to the Sydney 2000 Games, we look at the skill and thrill and reach in a man who made headlines the world over as a teen beyond his years in and out of water. On May 14-15, 2000, Thorpe added two more lines in the record books over 200m freestyle, having started his run taking down the 400m mark.

Part 1: Ian Thorpe – The Beginning: The Day The Thorpedo Launched at the World Champs (Video)

*******

Ian Thorpe, Thorpedo, Thorpey, the Pelé of the Pool and a boy with flippers for feet; a super-talent who could, like the likes of Roland Matthes and similar outer-orbiters of aquatic achievement, hold something in reserve for the final while breaking the World Record in a semi. The Australian was a swimmer who “gave the impression he could score highly for a triple twist off the 10-metre diving board if he wanted to”, as one national paper put it.

In fact, Thorpe’s most eye-catching plunge was his nose-dive of a false start at the 2004 Olympic trials, which required nimble handling and favours granted to get the champion to his blocks for the defence of the 400m freestyle crown in Athens (but that’s another story).

Back in May 2000, the world was more certain. It seemed, 20 years ago to this day as the boy wonder from Down Under made just about every home-market front page and headlines in almost 500 key publications around the world in a matter of a few hours after a third World record in as many days. He was declared “unstoppable”, even “invincible” by some rivals after two World marks over 200m freestyle – the first in 1:45.69 in the May 14 semi, the second a 1:45.51 in the May 15 final – came hot on the heels of a new 400m freestyle high bar.

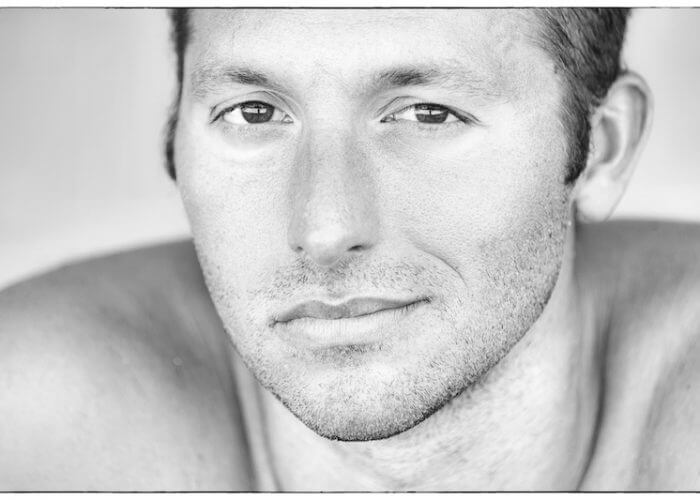

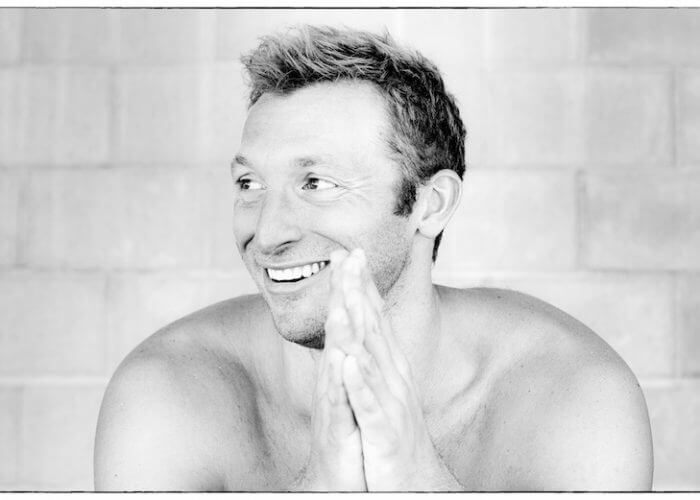

Ian Thorpe – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer ©

Heels his rivals were getting used to seeing just before more of the headlines Thorpe attracted this day two decades back.

- ‘Le nageur Ian Thorpe remet à flot le rêve olympique australien’, declared Le Monde in France

- ‘Australiens Schwimmstar Thorpe; Noch ein Weltrekord – Dritter Tag, dritter Start, dritter Weltrekord’, the Bavarian Süddeutsche Zeitung noted

- With the feet of a giant, explained the Neue Zürcher Zeitung in Switzerland

- ‘Thorpe, il Pelé delle piscine nato per battere record’ was Corriere della Sera’s take

- ‘Three Records in 3 Days for Australia’s Thorpe’, The New York Times told Americans yet unaware that their own BigFoot was about to break cover

- Ian Thorpe, un “torpedo explosivo con aletas” (a finned, explosive torpedo), blasted Spain’s ABC

- while Brazil’s O Globe Natação had Gustavo Borges telling his nation “It’ll be hard to stop him”.

A Dutchman would beg to differ at the Sydney 2000 Games but on the way to a boiling battle with Pieter van den Hoogenband, Ian Thorpe claimed “ownership of the Sydney Olympic pool” wrote Nicole Jeffery in The Australian on a day when Dolphins head coach Don Talbot tried to play it all down with a warning that the teen needed “to be a boy before he can become the greatest swimmer in history”.

Jeffery had Talbot saying Thorpey looked a little tired and needed to “go surfing” for two weeks after the Olympic trials. Said the head coach:

“He looks a bit drawn in the face to me, there’s some stress showing. He’s a boy and he needs some time to do boy things. Everyone wants a piece of him and far too many people are getting it.”

Thorpe must be protected as a priceless asset, Talbot indicated when he said:

“I go to bed each night and pray: `Please God let him be all right to the Olympic Games’. He’s an astonishing swimmer. I have run out of superlatives. I haven’t seen a swimmer who can do what he does, but he’s still a young man.”

A few years later after Bill Sweetenham, The Australian who became National Performance Director for Britain, had said of a Smart Track talent program that “the purpose is to find our own Thorpe – there’s one out there; we just have to find him”, he was asked how ‘precious’ he was to the Dolphins. Said Sweetenham:

“Mate, if I was in charge of Australian swimming right now, I’d be making sure Ian’s parents were going out on as many candle-lit dinners as I possibly could.”

Thorpe’s manager David Flaskas said it had been a long run into trials for his teenage client. There had been four “major issues” taking their toll on Thorpe.

Ian Thorpe – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

In October 1999, he had fractured his ankle. Then in February of Olympic year, this author broke the story in The Times in London that Thorpe had been accused of taking drugs by a German coach while in Sheffield on World Cup tour. The circuit moved to Berlin, where Jeffery reported a stand-off over the drug-testing procedures at the meet. The bodysuit saga and schism followed.

“He’s coped brilliantly, as we can see from his swimming this week,” Flaskas said. It certainly showed in the water.

Superlatives oozed from the pages of Aussie newspapers after Thorpe told reporters that he “still had a little left” after a 1:45.69 in semis, putting an instant price on the new global target:

“I don’t know if anyone else ever got bored breaking world records, but I sure don’t. This has taken a lot of pressure off me knowing I’m already in the Olympic team (in the 400m). Now I can take it out how I like, swim it how I want.”

His splits in the semi were slower than the world record pace he’d set the previous August for the second of his 200m World records, a 1:46.00. At the last turn, he was 0.17sec behind schedule. Off the wall with the kind of surge a seal fears when it spots a large black object heading towards it in the swell, the body-suited Thorpe gathered momentum and turned on the burners of his size 15s to drive his fluent, gliding, high-riding stroke to a fireball finish.

He was 17 and one observer wrote what Australians and many others thought to be a reasonable conclusion at a time before the Eindhoven Express arrived in Sydney: “Thorpe remains on target to become the first man in the metric era to treble the 100m-200m-400m freestyle at the Australian championship”. As it turned out, it was 100m bronze, 200m silver and 400m gold, with golds in the 4x100m and 4x200m freestyle making it a record tally for an Australian man in the pool.

Talk of Thorpe’s potential reached a state of fever pitch at Aussie trials in 2000. The 100-400m range was clearly not enough for a pioneer of pioneers. Sure, let Kieren Perkins and Grant Hackett have a last crack at it but watch out for Thorpe over 30 lengths the moment he felt like it, was the tone of chatter, though not among the coaches closest to him. Said his coach Doug Frost to national media:

“I’m dead-set against him swimming the 1500, if you really want to know. You can print that. It’s going to dull his speed, and we really want to develop his speed.”

Australia head coach Don Talbot agreed.

Ian Thorpe – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

Ian Thorpe & His 400m Prospects

Frost said Thorpe could one day crack 3:40 in the 400m (he was less than a tenth away from that at his best, in 2002) but it would take more than one Olympics to turn his charge into a genuine champion.

“We’ve talked about it … if you want to go down in history as one of the greatest swimmers of all time you’ve got to do it at an Olympics, and you’ve got to reproduce it at probably two or three (Olympics) if you want to stamp yourself as the swimmer of the century.”

It would turn out that that wasn’t what Thorpe wanted. It was what Michael Phelps wanted – and in amassing 23 Olympic golds atop 28 medals at four of his five Olympics, the American may well own the century come its close.

No-one, not Bob Bowman, nor Phelps nor anyone shy of God himself, even the faithless might admit, had seen that lot coming back on May 15, 2000 as Thorpe emerged with the 10th World freestyle record. The run, with more to come (12 in all, in fact, half solos, half relays), would take him to a record tally of 19 freestyle World records, 13 of them solo.

Little wonder that Michael Cowley, then of the Sydney Morning Herald, started his column this day 20 years ago a journalist who found it “a little disconcerting to find yourself stumbling and fumbling through the dictionary in search of a new, perfect superlative”, especially when Thorpe had just shot to pioneering pace for a third time in as many days even though his goggles had been filled with water.

Cowley dug deep and found one: Thorpesque. Thorpey’s rivals seemed to agree.

Michael Klim, the World champion who claimed the second berth for the 200m at Sydney 2000 in 1:46.89, said of Thorpe:

“He’s awesome. Every day he gets better. My goal was to do my best and I thought my best would be good enough [to qualify, not win).”

Klim stuck to Thorpe even if the glue was mostly somewhere between the pace-setter’s ear and shoulder. For the first 30m of the last length, Klim’s refusal to let go was impressive but the stickiness in him came unstuck from 20m out when the human flipper up front thought it time to separate the boy from the men in a final that featured seven Australia Pan Pacific Championship teammates, the fastest 7 200m men in Dolphins history.

Seems there was still something in reserve, or at least forced reserve. Said Thorpe:

“My goggles filled up with water and I didn’t see him [Klim] at all during the whole race, so I just swam my own race. I’m pretty excited tonight about getting an individual swim [in the 200m].”

There was this, too, from Thorpe: “I had a headache and felt sick in the stomach. I felt terrible when I got out of the water and I just wanted to get it checked with the doctor.” He’d had a migraine before, just before he cracked the World short-course record a year before, so “no worries, mate”.

After Thorpe and Klim came Grant Hackett (3rd, 1:47.81), Bill Kirby (4th, 1:48.05), Daniel Kowalski (5th, 1:48.13) Todd Pearson (6th, 1:48.15), the legendary Kieren Perkins (1:50.02) heading for a last fight with Hackett over 30 gruellers, and Anthony Matkovich (1:50.10). The 4x200m world would struggle come the big one.

Beyond His Years

Ian Thorpe – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

Ian Thorpe was not only mature beyond his years in the water. During those trials at 17, he’d had the presence of mind to tap coach Ken Wood on the shoulder and ask him if he could do one of his young charges a favour. He’d noticed that Wood had a 14-year-old called Leisel Jones on his hands.

“That’s the age I was when I was first selected for Australia, so I was wondering if you’d like me to have a chat with her before she swims her final (of the 100m breaststroke) to let her know what to expect,” Thorpe was reported to have said to Wood.

Done!

Wood was dumbfounded and told the Australian media: “What can you say about a 17-year-old who would make an offer like that when he has so much else going on in his life? He is just amazing.”

Grant Hackett had experienced the glow, too. He’d been drowning in his sorrows of a 3:51 in the 400m on day 1 at trials when the phone in his hotel room rang out.

As Wayne Smith, reporter on the Australian put it: “It was the man who had just thrashed him in the pool. ‘You OK?’ Thorpe asked him. There was no gloating, no teasing in Thorpe’s voice. Just concern for a respected rival.”

“Where does he get that sort of maturity?” Hackett would ask later. Frost had an answer: “We set standards.”

We meant Thorpe’s parents Ken and Margaret and his sister Christina, who also represented Australia. Then there was the role model in lane 8 in that 200m final at trials: Kieren Perkins. Frost told Smith:

“Kieren has been such a great role model to all the young kids coming up. Ian learnt a lot by studying him.”

The Warm-up For Bodysuit Wars

By 2000, it was Perkins who was learning lessons from Thorpe: both wore the Adidas bodysuit, the man at his third Games, the boy at his first. The same suit had been worn by Olympic and World-Championship podium placer Paul Palmer and Britain teammates Sue Rolph, sprint freestyle European champion, among a fair few others but it was when The Thorpedo didn’t don a Speedo but wore the German three-stripes brand from wrist to neck and from there down to ankle but not toe that the world and his wife sat up and noticed.

The Sydney Morning Herald asked some big names of coaching what they made of it. Forbes Carlile, hall of fame coach, father of the pace clock and mentor to Shane Gould and many others down the years, was blunt:

“Ian Thorpe may be right in claiming that it is ‘hard training’ rather than [it being down to] high-tech fabrics and various other attached devices which have contributed most to the highest standard of swimming we have yet seen by Australians.

“I shall be convinced that Ian is right when I see more of our top performers racing, and setting their times in the attractive brief suits which saw our champions of the recent past make their records. The integrity of swimming as a “pure sport” is at stake, where we can be sure the swimmer, not the equipment used, determines the winner.”

It was a message Carlile maintained throughout his life but most fervently during the shiny suits saga. The Adidas suit was supposed to have “gripper fabric” that could “grip and feel the water” and reduce drag.

“One must ask to what extent sponsorship of the sport and endorsement fees to leading swimmers and coaches have influenced this radical change. ‘World records’ set by swimmers wearing one of these novelty suits should be asterisk-marked, viz. ‘Novelty Suit Record’,” wrote Canadian coach, mentor and author Cecil Colwin.

Thorpe, via towering moments in 2001, 2002 and 2003 weathered all of that and kept his textile bodysuit on (in water) for the rest of a stellar career. The last time we saw Thorpe in thrilling form, he was retaining the Olympic 400m free title in Athens and adding the 200m to his pantheon ahead of Van den Hoogenband four years after lessons learned at a home Games.

At the time there was no writing about him going out at the height of his power. He would race on. In reality he never did again. There was a comeback, but that ended with hope at Australian trials for London 2012 in Adelaide when the 29-year-old Thorpedo fizzled out of the 100m freestyle heats on 50.35 in 21st places, the 41st best time of the career of a man who first entered the world rankings in the 100m with a 50.21 effort at the age of 15 back in 1998; the year he claimed the world 400m freestyle crown to become the youngest world swimming champion among men in history.

Over 100m, he would take bronze at Athens 2004 in in 48.52 to become the first man in history to stand on an Olympic podium over 100m, 200m and 400m at the same Games. The 200m and 400m delivered gold.

Ian Thorpe – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

In Adelaide, Thorpe was far from rolling back the year: he finished almost 2sec down on world champion James Magnussen out in front and a generation ahead on 48.26. Klim was also on the comeback trail and lived to fight another session on 49.79sec in 11th place. The former teammates had battled each other in solo races and bolstered each other as relay mates, most famously in the Sydney 2000 4x100m free relay.

Thorpe looked dejected after his 100m heat. Wayne Smith, of The Australian, wrote:

“He moved slowly to the side of the pool, so slowly that he still was in the water when the next heat started. Under normal circumstances the officials would not have even started the race while a swimmer was in the water but, as when he failed on Friday night (over 200m), there was a stunned hush around the pool and no-one could bring himself to give the five-times Olympic champion the hurry-up.”

Thorpe took his time but knew what to say. He had read the runes, felt fast water waving farewell. He emerged to say:

“I don’t want to be the old man who can’t do things – to push out something that may not be realistic any more. Although I am going to continue swimming, realistically I don’t think I will be able to get back to a position where I am at the top of the sport.”

And that was fine. His pantheon was stacked. He’d done more than enough by the time he said he’d be moving on. It was late July 2013, 16 years beyond the birth of Australian Swimmer Number 494 at the age of 14.

Krishnaraj Chaturvedi