How the Underwater Dolphin Kick Evolved Over Time and Revolutionized the Sport

How the Underwater Dolphin Kick Evolved and Revolutionized the Sport

By J.P. Mortenson (Archive)

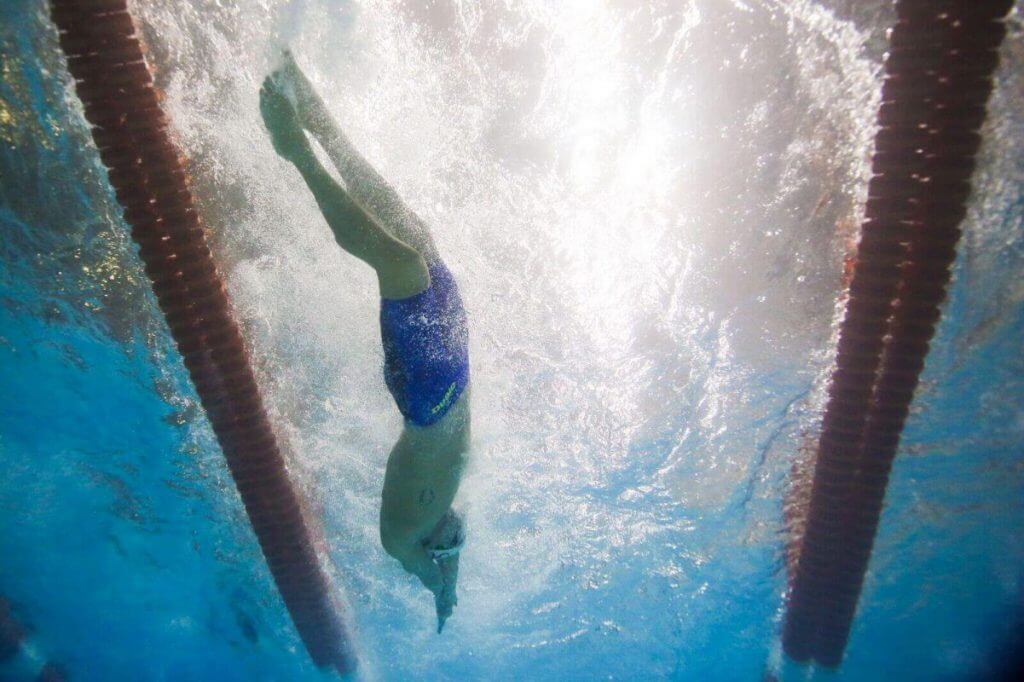

Underwater dolphin kicking transformed the sport of swimming. These days, swimmers at the NCAA and international level routinely push their kicks to the 15-meter mark. However, this was not always the case.

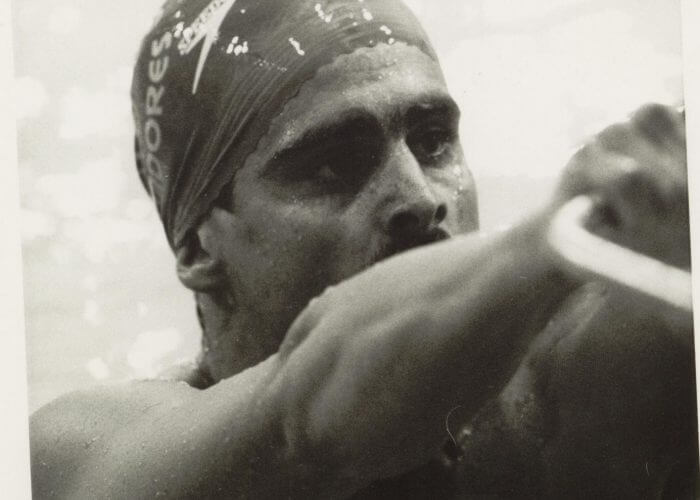

For a long time, dolphin kick was predominantly only used in butterfly. The first swimmer to utilize underwater dolphin kicks off of their turns was American Jesse Vassallo, who began to do two or three underwater dolphin kicks off of his starts and turns in the 1970s. According to Vassallo, the purpose of these dolphin kicks was “to avoid waves from bigger swimmers” and to help stabilize his body before starting his arm strokes. However, his utilization of the underwater dolphin was relatively limited, as kicks never extended past the first few meters. Although it was effective, the impact that it had on swimming was minor.

Vassallo, one of the pioneers of the underwater dolphin kick. Photo Courtesy: Chris Georges

In the 1980s, Japanese backstroker Daichi Suzuki began to explore Vassallo’s idea of utilizing underwater dolphin kicks in his races. However, he pushed for underwater dolphin kick for far longer distances. By the 1984 Olympics, Suzuki was going roughly 25m of underwater dolphin kick off of his start in the 100m backstroke. Despite this feat, Suzuki was unable to qualify for the backstroke finals so that it would be a few more years more years before the rest of the swimming world would catch on.

Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Archive

Meanwhile, in 1987, Stanford swimmers Jay Mortenson and Sean Murphy got the idea to use underwater dolphin kicks for the majority of their races.

According to Mortenson, he and Murphy got their inspiration when they “heard about a female backstroker in the SEC (Dawn Hewitt) who had a long history of shoulder injuries. Because of this, she extended her underwater dolphin kick to take fewer strokes. The fact that she was still able to compete at an elite level by using her underwater dolphin kick gave us the idea to try it. We started playing around with the underwater dolphin kick in practice in January of 1987, and we realized that it was significantly faster than swimming backstroke on the surface.”

In April of that year, they became the first swimmers to implement extended underwater dolphin kicking in their races at the NCAA level. Because there was no 15-meter mark restricting the amount of underwater dolphin kick that they could do at that time, they were able to swim more of their race underwater than swimmers can now. Regarding his 100 backstroke races, Mortenson says, “On the first lap I took one stroke, the second and third laps I took three strokes, and on the final lap, I was gassed, so I only made it halfway underwater before breaking out.”

The results of the Stanford swimmers’ experiment were extremely successful. While leading off Stanford’s 400 medley relay, Mortenson broke the American Record and became the first man to break 48 seconds in the 100 backstroke. In the individual event, Mortenson finished second, and Murphy finished third.

Another one of the first swimmers to turn heads with the underwater dolphin kick was American David Berkoff. Berkoff was both the most iconic and the most effective underwater dolphin kicker from the late 1980s, as he several world records in the 100 backstroke and routinely kicked underwater for 35 meters off the start of the race. His starts were so effective that announcers coined them as the “Berkoff Blastoff,” a name that would be used to reference underwater dolphin kicks for decades.

The idea to push underwaters caught on like wildfire in the swimming community. At the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, five out of the eight swimmers in the men’s 100m backstroke final dolphin kicked underwater for 20 meters or more off of their starts in a race that saw Suzuki out-touch Berkoff.

The era of pushing underwater was short-lived, however, as FINA – the sport’s international governing body – decided that they did not want the sport to go in this direction. In 1991, they banned underwater swimming in the backstroke for more than 10 meters, then later changed it to 15 meters.

Despite the early success of the swimmers who pushed the underwater dolphin kicks, few swimmers attempted to maximize the available 15 meters of underwater opportunity. Many acclaimed swimmers and coaches thought the underwater swimmer’s success was a fluke. The consensus belief among the swimming community was that swimmers who pushed their underwaters would fade at the end of their races due to pure exhaustion, thus negating what benefits they may have accrued from earlier in the race – especially for events longer than 100 meters.

The swimming community was also heavily concerned with safety, as coaches feared that swimmers could pass out while training their underwater dolphin kick. Due to these issues, it would be many years before underwater dolphin kicks would become a mainstay in swimming.

Obviously, it is undeniable that the 15-meter rule significantly limited the effectiveness of the underwater dolphin kick on long course backstroke. Nonetheless, they remained a staple of short course backstroke. The first backstroker to truly master the 15-meter limit was American Neil Walker. Walker dominated backstroke events at NCAAs, and his 1997 100-yard backstroke record of 44.92 stood for nine years.

Walker also had an impact on the international scale, as he routinely beat the four-time Olympic gold medalist Lenny Krayzelburg in the short course meters. He was able to get ahead of the field by utilizing the underwater off of the extra walls that short course offered, showing the world that underwater dolphin kicks were still very effective despite being limited to 15 meters.

The next stage in the underwater dolphin kick’s evolution was its implementation in other strokes. The most famous example of this occurred in the late 1990s when Misty Hyman, a rising butterfly star, began to dolphin kick underwater as long as she could off of her starts and turns. Hyman also kicked on her side to enhance the stroke’s effects. By 1997, she started winning butterfly races by swimming 35 meters underwater. Hyman’s innovation paid off in a big way at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, when she upset the reigning gold medalist, Susie O’Neill, in the 200 Butterfly.

By the time the mid-2000s came around, many of the elite swimmers from that era – including Michael Phelps, Natalie Coughlin, Ryan Lochte, and Aaron Piersol – had trained underwaters for much of their careers and and relied on them to win countless medals at the international level.

Phelps’ underwater dolphin kicks were one the main reasons why he famously won eight gold medals at the 2008 Olympics, as he did exactly eight dolphin kicks off almost every one of his walls with the exception of his 400 IM.

So this brings up the question: where to from here?

Even today, the world’s elite swimmers keep finding innovative ways to evolve underwater dolphin kicks. For instance, modern sprinters continue to push their underwater dolphin kicks in the 50 freestyle. The best example of this is Caeleb Dressel, who is the American record holder in both the 50-yard and 50-meter freestyle. Off of his starts in the 50, Dressel pushes his underwater dolphin kicks farther than his competition and breaks out near the 15-meter limit.

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://vmrw8k5h.tinifycdn.com/news/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/caeleb-underwater.mp4?_=1Although Dressel is obviously an exception due to his exceptional underwater dolphin kick, his competition is also pushing underwater dolphin kicks further, as most elite sprinters are now breaking out around the 10-meter mark in their 50 freestyle. This is significantly farther than 50 freestylers as recent as 10 years ago, as they used to believe that the fastest strategy was to start swimming as fast as possible. However, Dressel and the new age of 50 freestylers have proven otherwise.

It is clear both from the innovation trends and science that the underwater dolphin kick is going to remain a mainstay in the sport just because it is more efficient than surface swimming. Studies have continually proved this. The reason why underwater dolphin kick has shown to be so effective is that although kicking underwater is slightly faster than swimming on the surface, it allows swimmers to carry their speed from their dives and turns.

- Max speed in the air after a dive: ~6 m/s

- Max speed during the glide phase after a dive: ~4 m/s

- Max speed during the glide phase after a turn: ~3 m/s

- Max underwater kick speed: ~2.2 m/s

- Max swim speed: ~2.1 m/s

In other words, underwater dolphin kicks essentially allow swimmers to delay the inevitable slowing-down process from the fastest parts of their races. You can clearly see the effectiveness of underwater dolphin kicks in the video below.

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://vmrw8k5h.tinifycdn.com/news/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Underwater-Speed.mp4?_=2

Because underwater dolphin kicks have achieved such great results at the highest levels, more and more age group swimmers have started to practice them from a younger age. Thus, you can be sure that in the future, there will be more great underwater dolphin kickers who will find new and innovative to implement their underwater dolphin kicks to evolve the sport.

All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine nor its staff.

Edwin Schuessler

Martin N Snape you

Paul Kirihara

Christine Epps Tammy Kneer Minyard

Debby Patz—this article references the “Berkoff Blastoff!”

The swimmer with injury was dawn Hewitt ofauburn

Mackensey

What about Michael Klim??

Todd Peters made me think of you, hope your team has the best body dolphin there is.

Allie Hanson

Victoria Schachle

Steve good read

Rewriting History is not RIGHT… What about DENNIS PANKRATOV???… You never heard about him???…complete JOKE this article…

Please also give some credit to Gary Abraham, who represented Great Britain in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the Olympics, World Championships and Commonwealth Games competition, as well as swimming in the NCAA system in the U.S. for the University of Miami. I understand he was first to use not just the 3-5 extra kicks off walls that Vassallo came up with but to actually perform the bulk of the remaining trip down the pool underwater, as Berkoff and Suzuki also later did, before the backstroke underwater limits were legislated.

Please note Misty was winning races using her underwater technique well before 1997, having won a Spring National title in the 100 LCM Fly in 1994 and set a National HS 100 SCY Fly record (:52.41) that lasted nearly a decade. I believe it was at some point shortly after 1994 that Misty and her late coach, Bob Gillett — acknowledged by many as one of the creative geniuses of our sport — determined there was additional value in a fish tail kick, on her side rather than her belly, which was later legislated out of existence along with the underwater portions of the pool past 15 meters. Looking back on it, I believe Misty was also an example of how difficult it could be to balance the value of the additional distance and speed from the underwater fly technique against the inevitable increased oxygen debt induced by the extended period underwater. She was passed on the way home in many major fly races between 1994 and 2000, possibly feeling the effects of looking for the right time and distance to stay under off each start/wall. The effort to find her best technique off each wall was proven worthwhile in Sydney when, as normal, she led early but then also had the best final 50 M.

As you noted, it took a bit longer for great athletes in other strokes, who were always looking for an edge in their events, to adapt extended underwater techniques to their events also. Backstroke restrictions had come first, but it took well less than a decade for first butterfliers, such as Misty, and then even freestylers, to prove to the community that strong underwaters could produce greater velocity than surface swimming in every stroke. For example, Russia’s Denis Pankratov had Olympic Gold in 1996 in both the 100 and 200 Butterfly, and at least in the 100 I recall him being 35+ meters underwater off the start. The earliest over 15 Meters underwater freestyler I recall competing at the highest level, before the all strokes limitation to 15 Meters, was Catherine Fox of KC Blazers/Stanford.

Great info and explanations. Thank you.

Well, it beats being limited to only 2 dolphin kicks that were allowed in butterfly in the 1970’s. A lot of us 70’s swimmers would have been about 2 to 3 second faster in our strokes with allowing 15 meters or if we went past 5 meters.

Daniel Rodríguez Beltran

Underwater kicking was first developed & used in competition for the backstroke in New Zealand in the 1950’s. I was introduced to it in the States in the late 1950’s. This was also at the time that most breaststrokers in short course races swam as much of their races as possible underwater. At that time the butterfly was an evolving stoke & the 150 IM was the race, not the 200 IM….the choice being a 50 breast or fly at the front of the race, followed of course by the 50 back & 50 free [crawl].

Thanks, Frank. Good stuff! You have certainly been around the sport in enough of a cosmopolitan fashion, both in terms of time and location, to give real credibility to your comments/memories.

Tell us, as to the underwater backstroke kicking in the 1950s, were they using dolphin or a freestyle/crawl technique? I remember near that period doing inverted freestyle kick both off walls and within the swimming stroke, which was helpful to a degree but was substantially less effective than dolphin properly learned for use on one’s back eventually turned out to be off walls. Thanks again, Frank.

Duncan, it was a flutter kick off walls for the backstroke at that time. I really don’t remember seeing it again ’til the early 1080’s The fly’s dolphin kick was in its

earliest days then [late 1950’s]. I remember swimming 200 fly, as late as 1963 alternating the breast & the current fly kick by 25’s. At that time only the best, like you, could employ the fly kick through 200 yards.

No talk of Ian Crocker’s underwater dominance from 2003-07?

Personally, I’m not a fan. I like to think the fastest backstroker will win the backstroke race. The faster butterflyer the butterfly race etc.Not the best underwater dolphin. It also makes watching SCM and SCY super dull.

I’m really glad this article mentions Dawn Hewitt. I saw her swim in high school and then college, and both read about and saw her utilizing the underwater dolphin kick almost exclusively. She basically swam 50 backstroke with four arm pulls, mainly to make the turn and finish. She had to leave Auburn swimming and finish with the University of South Florida, where she helped them win a championship. There have been a couple of other articles about the underwater backstroke kick that mentioned her; I think it’s very likely that she was the first elite level swimmer that showed how fast the underwater backstroke kick was.

Darryl rapp a swimmer for ATAC swimming in Tallahassee in the late 1970s was swimming 35 Mtrs Uw LC and then went on to success at Yale

Darryl Rapp went 35 meters underwater swimming for ATAC in Tallahassee in early 80s and then continued to use it while swimming at Yale

Interesting article but Gary Abraham of GB used this to great effect in the Moscow Olympics in 1980…. Watch the videos. He was ahead of his time