How the Tsar, Alexander Popov, Claimed the Sprint Throne

Editorial content for the 2021 Tokyo Olympic Games coverage is sponsored by GMX7.

See full event coverage. Follow GMX7 on Instagram at @GMX7training #gmx7

How the Tsar, Alexander Popov, Claimed the Sprint Throne

We take a look at the career of Russian sprint legend Alexander Popov, whose combination of skill and work ethic carried him to greatness.

He knew how to play the all-important mental game of high-level sports with the skill of a chess master. Every move was calculated. As Alexander Popov scanned the ready room before a major race, it was not unusual for the Russian star to chat up the opposition. He would throw out a joke or two, a few laughs generated along the way. But in the laughter he elicited, Popov was already gaining an advantage over his foes, as he planted a seed of doubt here and a distractive thought there.

With that part of his job done, he would then shift personas, the affable jokester replaced by a fierce competitor with an icy stare and a take-them-out mentality. The moment Popov walked onto the deck, it was all business. He knew his goal, and it was simple: Destroy.

From an athletic standpoint, Popov was the epitome of perfection in the sprint-freestyle events. He boasted a flawless stroke, one that is still revered. The relationship he shared with coach Gennadi Touretski was as much father-son in its dynamic as it was mentor-pupil. Then there was his inner drive, so high in its intensity that it is difficult to describe.

As we continue our Takeoff to Tokyo series, the opportunity to examine the career of Popov – accomplishments and approach – is the chance to pay tribute to a man who might be the greatest sprinter the sport has seen.

The Rise of Popov

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was no question that Americans Matt Biondi and Tom Jager ranked as the sport’s Kings of Speed. While Biondi captured the Olympic title at the 1988 Games in Seoul, Jager was a two-time world champion and the world-record holder.

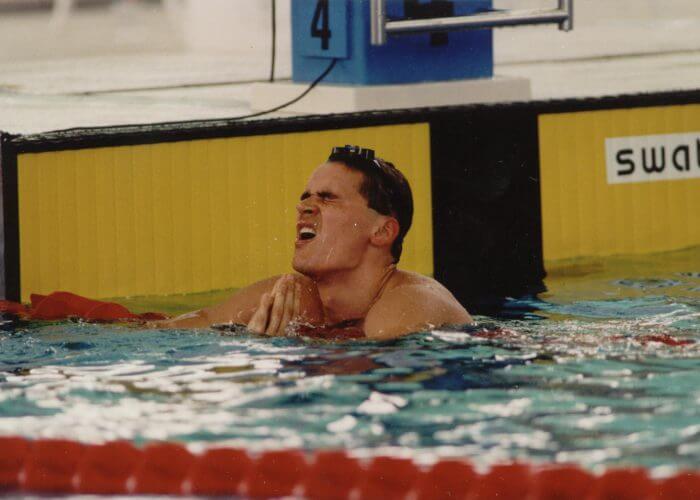

Photo Courtesy: Tim Morse

As dominant as Biondi and Jager were, though, there were rumblings that a young challenger was on the way. Of course, Popov was that man, and when he captured the European crown in the 100 freestyle in 1991, his presence became bolder. A year later, at the Olympic Games in Barcelona, Popov fulfilled the expectations placed upon his shoulders.

In his first Olympic appearance, Popov swept the sprint-freestyle events, prevailing in 21.91 in the 50 freestyle and 49.02 in the 100 freestyle. It was the one-lap sprint that truly solidified his status as the Sprint Tsar, as Popov beat Biondi and Jager in comfortable fashion. The fact that there was a changing of the guard was not lost on the Americans.

“Popov obviously had the courage to stand up to Matt Biondi and Tom Jager and take them down,” Jager said. “The first person in the world to do that. I take my hat off to Popov. He has a great career ahead of him.”

Jager’s foresight was perfectly on target. After supplanting the American legends on the sprint scene, Popov sandwiched sprint sweeps at the European Championships around a sprint double at the 1994 World Championships in Rome. There was no letup from a guy who wanted to take his opponents’ will and desire with his mere presence.

As he surged to untouchable status, Popov also claimed the first world record of his career when he fired off a 48.21 clocking in the 100 freestyle in 1994, a standard that endured for six years. The work he put in came under the guidance of Touretski, who took Popov with him when he accepted the head-coaching position at the Australian Institute of Sport in 1992.

“When I go to competitions in Europe or America, or even here in Australia, I am always looking for potential challengers,” Popov said. “If I see any, I have to swim faster and make them feel sick. If they have a little potential, you must get on top of them and kill that enthusiasm right away so they will lose their interest in swimming.”

Greatness in Repeat

Ahead of the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, Popov was cemented as the heavy favorite to mine gold in the 50 free and 100 free. But repeating on the Olympic stage had proven to be one of the most-difficult tasks in sports, and nothing was a given – even with Popov. Aside from the pressure of the situation, Popov had to deal with the latest American sprint star, Gary Hall Jr.

Hailing from a family with a rich lineage in the sport, headlined by Gary Hall Sr.’s three Olympic trips, Junior was armed with considerable talent of his own. At the 1994 World Champs, Hall Jr. was second to the Russian in both sprints, performances that noted he would be a factor in the ensuing years.

Hailing from a family with a rich lineage in the sport, headlined by Gary Hall Sr.’s three Olympic trips, Junior was armed with considerable talent of his own. At the 1994 World Champs, Hall Jr. was second to the Russian in both sprints, performances that noted he would be a factor in the ensuing years.

The first duel between Popov and Hall Jr. at the Atlanta Games was in the 100 freestyle and while Hall gave his rival more of a push than expected over the two-lap distance, it was Popov who emerged on top, 48.74 to 48.81. Three days later, Popov got the job done again, this time winning the 50 freestyle in 22.13, with Hall grabbing silver in 22.26.

By retaining his 100 freestyle title, Popov became the first man to go back-to-back in the event at the Olympics since American legend Johnny Weissmuller doubled in 1924 and 1928. More, the rivalry with Hall Jr. was on, with the men exchanging barbs at various times. It was Popov who hurled the first grenade. Not only did he take umbrage with Hall’s relaxed and colorful style, one that included shadow-boxing routines before races, he took a shot at Hall’s family.

“He doesn’t work hard,” Popov said of his rival. “He’s doing 1500 meters? That’s what I swim in warmups. “(Hall) says he will be at the Sydney Olympics and that he will win both sprint titles. I don’t know how he can say that. His father was never an Olympic champion, and he never will be either. It’s a family of losers.”

Not surprising, Popov’s words got back to Hall, who vowed to become an alchemist and turn his silver medals from Atlanta into gold at the 2000 Games in Sydney. He also felt the need to defend his family and father, an inductee into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

“(Popov) is the epitome of unsportsmanlike conduct,” Hall said. “In the world of swimming, Alexander brings a new definition to the word shallow. What really upsets me is that in order to make himself feel better, Alexander must put down the Olympic accomplishments of his opponent’s father. I am embarrassed for this coward of a man. He ought to quit now because that road is going to be a long and hard one. Or, he can learn the words of the Star Spangled Banner because that’s what Olympic audiences will be hearing for years to come.”

Bad Timing

On the road to Sydney, Popov found that Hall was the least of his concerns. In August of 1996, just weeks after he swept the sprint-freestyle events at the Atlanta Olympics, Popov was walking with friends on a Moscow street when members of his party got into an argument with watermelon vendors. The exchange of words quickly escalated into a physical altercation and one of the vendors stabbed Popov in the stomach. Popov was rushed to a hospital where he underwent a three-hour surgery to treat damage to his lungs and kidney.

Gennadi Touretski and Alex Popov

Popov spent 45 days in the hospital and resumed training three months after the incident, with his return to major competition arriving at the 1997 edition of the Santa Clara International Swim Meet, 10 months after the stabbing. After winning the 50 freestyle in Northern California, the only hint of his near-death experience was the six-inch scar on his chest.

“You know, we probably could have gotten out of the situation if it had been handled differently,” Popov said. “But they approached us, and somebody started talking with them, and they misunderstood us and started to fight. The men didn’t know who I was. We were in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Having dodged death, Popov went on to win gold in the 100 freestyle at the 1998 World Championships, in addition to earning silver in the 50 free. Meanwhile, just a few months before the Sydney Games, Popov crushed the world record in the 50 freestyle at the Russian Olympic Trials, going 21.64 to break Jager’s 10-year-old world record by .17.

In Sydney, Popov knew he had the opportunity to make history, and become the first man to win the same event at three straight Olympics. It was a goal Popov wanted badly.

“If you win the Olympics once, you’re good,” Popov said. “Win the Olympics two times, you’re great. Win the Olympics three times, you’re history.”

Ultimately, Popov didn’t have the same magic he spun in Barcelona and Atlanta. In the 100 freestyle, Popov captured the silver medal behind the Netherlands’ Pieter van den Hoogenband. In the 50 free, Popov missed the podium and was forced to watch Hall Jr. claim the gold medal, which he shared with American teammate Anthony Ervin.

Not Quite Done

If it looked like Popov was on the downside of his career following the Sydney Games, but the legendary sprinter, whose stroke has been described as a piece of art, proved otherwise while remaining in the sport. At the 2003 World Championships, Popov emerged once again as a double-sprint champion.

With two more world titles collected, Popov figured to be a factor at the 2004 Olympics in Athens. Instead, the meet was a disaster for the Hall of Famer, as Popov failed to advance out of the preliminaries of the 50 freestyle and was eliminated in the semifinals of the 100 freestyle. As quickly as Popov moved through the water, his career was over.

When he is remembered, Alexander Popov will be recalled for his perfect stroke. He will be lauded for his ability to deliver under pressure. He will be appreciated for etching himself as one of the greatest sprinters in history, perhaps the finest.

Simply, he had a special relationship with the pool.

“The water is your friend. You don’t have to fight with water, just share the same spirit as the water, and it will help you move,” he once said. “If you fight the water, it will defeat you. We were born in water. It’s like home to me.”

I saw him swim in Atlanta and was most impressed with his stroke. It just looked so easy.

Greastest swimmer ever.just love him

Alexander is the best and if he hadn’t got stabbed he would have won double gold again in Sydney.