How The Story Of Jesse Owens & Luz Long Shines Yet As A Beacon Of Hope For An End To Discrimination

“When I came back to my native country after all the stories about Hitler I couldn’t ride in the front of the bus. I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted. I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler, but I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President either” – Jesse Owens

Commentary: Against a backdrop of protest over racial discrimination in the United States in the wake of George Floyd‘s death after he gasped his last words – “I can’t breath” – under the knee of a policeman now charged with his murder, we take a look at a story from Olympic history that begs the question ‘how long will this lesson last’.

The story of the black American four-times Olympic Champion Jesse Owens and Germany’s Luz Long at the 1936 Olympic Games in a Swastika-soaked Berlin stadium offers powerful messages for humanity from the realm of sport. As noted in an extract below from the Olympic book Heat of the Moment:

“It was a question of a master athlete and a worthy competitor humiliating those who believed in a master race. The drama that played out in 1936 as Hitler watched is to this day widely cited as the prime example of how sportsmanship can triumph over the ugliest forms of competitiveness. What unfolded between Long and Owens and the message it sent to the wider world transcended athletics and stretch to global politics as the storm clouds gathered for one of the darkest periods in human history.”

In 2020, the story of Owens and Long and what they and their friendship stood for remains a lesson to be learned, learned anew and reinforced. The stirring story of Owens and Long speaks to the healing role that sport can but often does not play.

From the days of Jesse Owens and his four victories under a sea of swastikas at a Games sullied by propaganda, bigotry, hatred and racism on the eve of the Holocaust, elite athletes have been silenced by threats of expulsion and punishment from their guardians and governors.

Hold the thought. Kate Bush sang: “It’s been such a long week; So much crying; I no longer see a future; I’ve been told when I get older; That I’ll understand it all; But I’m not sure if I want to …”. Think back to your early childhood and if your memory allows, try to recall the sting of being rebuked, rubbished, discouraged, having a drawing or a garment of clothing or a way of being or a physical characteristic made the subject of fun or criticism, of being bullied. Think of the impact that may have had or did have on you. Now imagine that feeling being with you almost every day of your life since, through childhood and into adulthood, year-upon-year, decade-upon-decade. Crushing, convulsing, corrupting of the human spirit.

That’s the place where understanding can begin if we’re to fathom how #BlackLivesMatter is to convert protest to lasting change and an end to systemic and societal discrimination. It is the place where we find passionate response that requires our understanding and appreciation – and the kind of response to the battle-fatigue frustration of Simone Manuel that Swimming World felt essential not just in this most troubled of weeks but as a permanent shift in awareness and culture.

Sport is no stranger to the issues. Down the years, athlete agreements and official codes such as the Olympic Charter have at once contributed to solidarity and understanding among athletes and nations and contributed, regardless of good intent or otherwise – to the gagging of athletes – of all colours, creeds shapes and sizes. Rules clearly restrict the ability of athletes to stage peaceful protests in the face of the unacceptable, be that discrimination, doping or the exclusion of athletes and independent stakeholder representatives from the decision-making structures of sports governance far and wide.

What has that to do with the brutal death of George Floyd by suffocation under the knee of a police officer who shamed and tainted the status he held and now faces criminal charges along with the three other officers who were present and did nothing to prevent actions that officers are not trained to do and not permitted to do? Plenty, in the was of a tidal wave of protest in the United States and far beyond.

As with the world in general, the issues are nothing new to sport, nothing new to high achievers in sport who have made their feelings known peacefully and, indeed, been penalised for it.

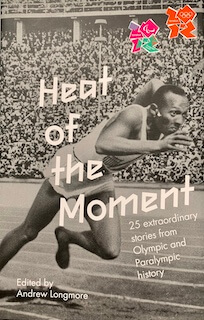

Photo Courtesy: Now This (video below)

Colin Kaepernick may well feel that current events represent the worst sort of vindication, that which comes at the cost of another life among many lost to discrimination, bigotry and hatred down decades and centuries, some and some part of economies and the perceptions of what defines the ‘strength’ of nations build on the blood spilled.

Kaepernik is the black athlete, NFL player, who began the “take a knee” protest against racial injustice and police brutality in 2016 is now being lauded afresh. Blackballed, labelled “unpatriotic”, “un-American” and much worse, ostracised by the guardians and governors of his sport, and referred to, with others, as a “son of a bitch” by the 45th president of the United States, Kaepernik is now finding now stance gathering significant and widespread support. His right to peaceful protest is being reconsidered, regained, reconnected with the issues he sought to highlight.

That follows reconsideration of such moments as Muhammed Ali‘s anti-Vietnam stance and the gloved-fists protests at the 1968 Olympic Games of athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

A Washington Post article under the headline “The message hasn’t changed’: NFL players find echoes of Colin Kaepernick’s protest across the country“, starts:

Anquan Boldin can see history repeating. In 2016 and the years to come, Boldin said, he watched as critics “hijacked” Colin Kaepernick’s message after he knelt during the national anthem before NFL games in protest of police killing and brutalizing black people. Rather than police reform, conversation swung to respecting the military and the American flag. Some – including President Trump – called for players to stick to football and for owners to fire those who protested.

“Those were the people who truly wanted to ignore what players were talking about,” Boldin said. “The message hasn’t changed from that time to now.”

A reminder:

Since then we’ve seen the knee taken by many others – and not only NFL players. In swimming, Anthony Ervin took the knee in 2017 as a reigning Olympic champion, while in 2020 we find the entire Liverpool football squad taking the knee as the wave of outrage over the death, by choking, of George Floyd goes global.

The issue polarises people in the United States, some believing the flag trumps all. Regardless of party politics, latest events have put a spotlight on two tribes: “make America Better” Vs “Make America Great Again”:

-

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour. I love America. I love people. That’s why I’m doing this. I want to help make America better.” – Colin Kaepernick, 2016

-

“Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field, right now, out? He’s fired.’” – Donald Trump on a campaign rally in Alabama, 2016.

Those words of a would-be president drew raucous cheers that day and made the nation’s most popular sport think twice about the consequences of hiring Kaepernick. NFL owners fell into line — taking the knee became punishable for a moment before that was deemed unenforceable, While the sport did employ athletes with a record of domestic violence and other questionable behaviour, it found no place for Kaepernick.

No surprise then, to find Kenny Stills, wide receiver for the Houston Texans, finding much support when he tweeted “save the bullshit” after the NFL put out a statement last weekend expressing sadness and “an urgent need for action”.

A process of education and understanding is underway and being played out in public in these digital days of social media. Drew Brees, renowned quarterback for the New Orleans Saints, was condemned by a team-mate after saying that he would “never agree with anybody disrespecting the flag”.

Malcolm Jenkins replied: “Drew Brees, if you don’t understand how hurtful, how insensitive your comments are you are part of the problem”. Brees acknowledged the lack of compassion and said he would strive to be more understanding. A time of learning for all.

Brees then took to social media to post a direct message to President Trump:

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBE4y_9Hj2S/?igshid=7ejunv7ktpcn

Swimming history includes exclusion, too. I recall one French international recalling a tale from the U.S. college he attended where the man in charge, an Olympic coach of several decades ago now, openly declared “No blacks in my pool!” That history is reflected in Jeff Wiltse’s Contested Waters and related work.

Sports Illustrated picked up the ‘taking the knee’ theme this week when it noted: “It was easy for Kaepernick’s detractors to portray him as an extremist four years ago. It’s not so easy now.” In that same article, SI also surfs the turning tide with these juxtaposing words: “In the right market, signing him [Kaepernick] would do wonders for a team’s image.”

Preceding good thought and action with “in the right market” misses the point. Meaningful change cannot be symbolic and “market driven”. It must come because we all get it, because we all want what Simone Manuel noted in a recent tweet as she watched the headlines rolling:

“Annnndddd other countries! Racism is everywhere. Let’s be the change. Let’s love each other so that we can create a better country and a better world.”

Annnndddd other countries! Racism is everywhere. Let’s be the change. Let’s love each other so that we can create a better country and a better world. https://t.co/ctjTEnQXNn

— Simone Manuel (@swimone) June 3, 2020

Which brings us to Jesse Owens and Luz Long – Brothers In Arms On The Field Of Sport.

The story (extracts in italics) is told in part through extracts taken from a chapter this author contributed to “Heat of the Moment – 25 extraordinary stories from Olympic and Paralympic history” published by Wiley in 2012 among the official publications of the London 2012 Olympic Games.

Jesse Owens & Luz Long, Brothers In Arms

Along the road from Catania in Sicily beyond a stone tablet framed with Bougainvillea and engraved Deutscher Soldaten 1939-1945′, the echoes of battle whisper of wisdom learned from more than one field of engagement. Among the 4,561 German lives lost on the island during the dying days of the Second World War and commemorated in the quiet cemetery of Motta Sant’Anastasia is a tale of heroism and friendship of epic proportions.

As the roar of guns and blast of bombs launched by the approaching Allied Forces grew louder in early July 1943, the thoughts of Luz Long, a 30-year old lawyer serving as a senior Lance-Corporal with the German Army, strayed back seven short but troubled years in a singularly important moment of sportsmanship: in a thronging Berlin 1936 Olympic Stadium soaked in swastikas and sullied by propaganda, the European Long Jump record holder and Leipzig law student had defied Adolf Hitler by embracing a symbol of all that the Nazis had set out to destroy.

Long would never know that a note he wrote to his friend Jesse Owens from the front in 1942, just after the United States declared war on Germany had reached the star of the Berlin 1936 Olympic Games, an African-American athlete whose race and colour spelled inferiority under Third Reich doctrine. Ridiculed for relying on “black auxiliaries”, the USA team was also scorned by one German official for allowing “non-humans like Owens and other negro athletes” to compete.

Owens shot all of that down in flames with athletic athletic superiority worth its weight in more than the four gold medals he won, the message reinforced through the very public friendship that Luz Long initiated during the Long Jump competition in front of a 110,000-strong crowd that stood to welcome Hitler with a mass Nazi salute. It was a question of a master athlete and a worthy competitor humiliating those who believed in a master race.

Reflecting on his own act of defiance in the face of brutality and discrimination as an athlete from Leipzig (a city that would rise up in 1989 and spark the collapse of the Berlin Wall and unite a divided Germany that he would never know), Long, husband and father, ricked much in 1942 by penning what would turn out to be a prophetic and haunting request:

“My dear friend Jesse,

My heart is telling me that this is perhaps the last letter I will ever write. If that’s the case, I beg one thing of you: when the war is over, please go to Germany, find my son Kai and tell him about his father. Tell him about the times when war did not separate us and tell him that things can be different between men in this world.

Your brother, Luz”

The Olympic silver medalist, who was born the year before Germany initiated the First World War, was wounded during the Allied invasion of Sicily on 10 July, 1943. Four days later (some records suggest three days), Carl Ludwig ‘Luz’ Long lost his life in a British controlled Military Hospital at San Pietro Clarenza and was buried at Motta Sant’Anastasia, where Albert Schweitzer’s words hang heavy in the air:

“The soldiers’ graves are the greatest preachers of peace.”

In 1951, Owens, in response to Lutz’s request, sought out and met Kai Long and told him that the friendship he had had with the boy’s father was the most valuable treasure he had kept from his Olympic experience.

The drama that played out in 1936 as Hitler watched is to this day widely cited as the prime example of how sportsmanship can triumph over the ugliest forms of competitiveness. What unfolded between Long and Owens and the message it sent to the wider world transcended athletics and stretch to global politics as the storm clouds gathered for one of the darkest periods in human history.

In athletic context, Owens had punctured the myth of an Aryan super race long before he arrived in Berlin. On 25 May, 1935, the son of a sharecropper and the grandson of slaves leapt 8.13n at Ann Arbor to set a world record that would survive 25 years and 79 days. The official program and subsequent approved reviews of the Olympic Games, one sponsored by a Hamburg tobacco manufacturer, sheds no light on that stunning performance: the 7.98m leap of Japan’s Chuhei Nambu from 1931 was the World record according to Nazi Germany.

The thumbprint of Nazi censorship visible on every page, the official Olympic report records the wonderful fight as follows:

“The German starts off with a 7.73 leap, while Owens suffers a foul jump. After that the Leipzig student manages a wonderful jump that shows his strong fighting spirit and the public rewards him with spontaneous applause: 7.87, the loudspeaker announces as Luz Long matches the ‘USA Wunderathleten’. The cheering refuses to die down as Owens gets ready for his second jump. Before he goes to the runway, he smiles at Long and congratulates him. He then storms down the runway and a moment after he leaves the board, he lands far in the depth of the pit: 7.94!!m Long puts all his efforts into his last attempt but misses the board. Owens in the meantime confirms his victory with a final jump of 8:06. That marks the first time in Olympic competition that the 8m mark is broken. His performance demands our singular admiration and Germany is proud to have put up a competitor who demanded the very best of Owens.”

Photo Courtesy: Heat of the Moment, John Wiley & Sons

In 1935, the Nazi regime effectively created two types of Germans: ‘citizens of pure race’ and ‘subjects’ to ‘protect German blood and honour’. Tall, blond, blue-eyed and athletic, Luz Long embodied the very idea of ‘Aryan’, while Owens was just about as remote from Hitler’s fantasy as was possible. The contrast was described in a 1936 report of the French sports newspaper L’Equipe as follows:

“Long, the typical Aryan, blond locks tumbling onto his forehead, honed body, robust, battling against a black man under surveillance.”

Other takes on those events included one from a leading American Sports writer there that day. Grantland Rice wrote: “As he hurled himself through space … Owens seem to be jumping clear out of Germany.”

At 8:06m, a stunning moment caught by Leni Riefenstahl‘s team for her Nazi-approved documentary of the Games, Owens proved himself a class apart. Long fouled his last attempt before the top two finishers walked arm-in-arm off the field towards the dressing rooms. As noted in “Heat of the Moment”:

“Hitler did not present the medals nor did he ever congratulate Owens, the star of the Berlin show. Instead, he cowered near the athletes’ exit so that he could shake the hand of the German athlete who had made the de rigueur Nazi salute on the Rostrum. One evening in the Olympic Village, Owens and Long met for a private talk, according to some accounts. It was the last time the two would ever meet, though the connection between the athletes survives to this day.”

At the 2009 World Athletics Championships in Berlin, Kai Long, then 70, and his daughter and granddaughter of Luz Long, Julia-Vanessa Long, and Marlena Dortch, one of Jesse Owens’ granddaughters, shared a platform in memory of the friendship formed in the same stadium in 1936. Kai Long recalled meetings with Jesse Owens in 1951, 1964 and said: “We first met in 1951. Jesse Owens came with the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team. We met in Hamburg and he was dressed very smartly. He came to see if I would come there.”

As part of the celebrations, Owens ran a lap of honour in the 1936 stadium in 1951 in front of 80,000 cheering fans. He was greeted by the Bürgermeister of West Berlin with the words:

“Jesse Owens, 15 years ago Hitler would not greet you or shake your hand. I will try to make up for it today by taking both of them.”

We return to the story as told in Heat of the Moment: “In 1964 Owens returned to Germany for the filming of the documentary ‘Jesse Owens Returns to Berlin’, in which he recreated that 1951 lap of honour for the cameras. It was a poignant moment for an ageing athlete.

“I had many thoughts as I ran,” said Owens, who dedicated his Memoirs to Luz Long. “As I passed each section. There was a bridge to the past. I passed that platform of champions where four times I stood to receive the gold medal … the sounds of the past are in the walls and the archways and the very ground I am standing on, for here time has always stood still.”

The 1964 film reflects the 1951 photographs of Owens meeting Luz Long for the first time. The snaps were donated to the German Sports Museum in Berlin in 2009, the year Kai Long was asked for his thoughts on the courage it took his father to befriend Owens in front of Hitler. Said Kai Long:

“I think it is not a question of race black and white. It’s about the spirit of the amateur athletes. the action of the clean amateurs. I was told it was absolutely about that in amateur sports: to help each other. What my father did probably happened several times during the 1936 Olympics. But Jesse, of course, said it was a fantastic thing that his opponent was ready to help him through the qualifications … this was a little spark. Not an action but a little fire lit by Jesse Owens … this fire got brighter and brighter and is still burning. There was no ‘action’, it just happened. All I know is what my family and friends told me. It was a normal occurrence in sport.”

In the Heat of the Moment chapter “Brothers in Arms”, the story concludes:

Against the backdrop of 1936, it was also, arguably, the greatest gesture in the history of sport.

Long, bronze medallist at the European championships in 1934, continued to compete after the 1936 Games, and in 1937 recorded a lifetime best of 7.90m. He finished law school that year and practiced briefly in Hamburg before all healthy men were drafted to fight for the Nazis. He did so until that fateful July day in Sicily.

The story [of Owens and Long] will not fade with time, so resonant is its message to humankind. Yet there remains deep contrast between the way the two men who shook hands and formed a friendship in defiance of Hitler back in 1936 have been treated in the intervening years.

Years after the 1936 Games, Owens was asked about ‘the Hitler snub’ and replied:

“When I came back to my native country after all the stories about Hitler I couldn’t ride in the front of the bus. I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted. I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler, but I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President either.”

Things would be a touch different by the time he died.

In Berlin, the street leading to the Olympic stadium is named Jesse Owens Allee – the great athlete’s family having attended the dedication ceremony as guests of the German Government in 1982, two years after Owens, a smoker, died of lung cancer. In tributes to Owens, US President Jimmy Carter said:

“Perhaps no athlete better symbolized the human struggle against tyranny, poverty and racial bigotry. His personal triumphs as a world-class athlete and record holder were the prelude to a career devoted to helping others. His work with young athletes, as an unofficial ambassador overseas and a spokesman for freedom are a rich legacy to his fellow Americans.”

In 1990, US President George H.W. Bush posthumously awarded Owens the Congressional Gold Medal, calling his victories in Berlin:

“… an unrivalled athletic triumph, but more than that, a triumph for all humanity.”

Perhaps time will be kinder to Luz Long, too. In Germany to this day, there is scant official recognition of a man posthumously awarded the Pierre de Coubertin Medal, or True Spirit of Sportsmanship Medal, by the Olympic movement.

The Leipziger Sports-Club 1901, for which Long competed has no track and field athletes these days, tennis, hockey, football and snooker being the only sports represented. While Long’s medal and some of his personal possessions and letters are preserved at the Leipzig Sports Museum, there is no sports hall, no stadium, not even a long jump strip named after him. Long has never been awarded any German prize nor is there one named in his memory.

In Leipzig, you can wander along Luz Long Weg and peer over a hedge at an athletics track. That remains the only honour afforded to one of the central characters of the 1936 Olympic Games by his – and the host – country.

Footnote At A Time Of Dire Straits:

There’s so many different worlds

So many different suns

And we have just one world

But we live in different ones

Now the sun’s gone to hell and

The moon’s riding high

Let me bid you farewell

Every man has to die

But it’s written in the starlight

And every line in your palm

We’re fools to make war

On our brothers in arms

– Mark Knopfler – Dire Straits

- All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine, the International Swimming Hall of Fame, nor its staff.