How Cate Campbell Redefined Success After Her Lowest Juncture

By David Rieder.

When Cate Campbell swam at the Pan Pacific Championships in Tokyo last month, it was “a dream week in the pool.” She won five gold medals, swam the second-fastest time in history in the 100 free and recorded historic splits anchoring three different relays to the top of the podium.

“Every time I hit the water, it was just magic. I can’t really tell you why that happened,” Campbell said. “I’m not going to lie—it felt really, really good.”

But Campbell knew to be careful with success—to not let herself scrutinize her races and convince herself she should have been better, to not let her accomplishments “worm into being part of my identity.” She had been there and done that—and the aftermath was not pretty.

By now, the story has been retold ad nauseum. Campbell went to the 2016 Olympics as a heavy gold-medal favorite in two individual events and came up well short both times. With little else to fall back on, Campbell was devastated.

“Swimming had become my whole world back in 2016,” she said. “It happened very slowly, but by the time we got to Rio, I had very little else in my life that I could draw joy from or draw perspective from.”

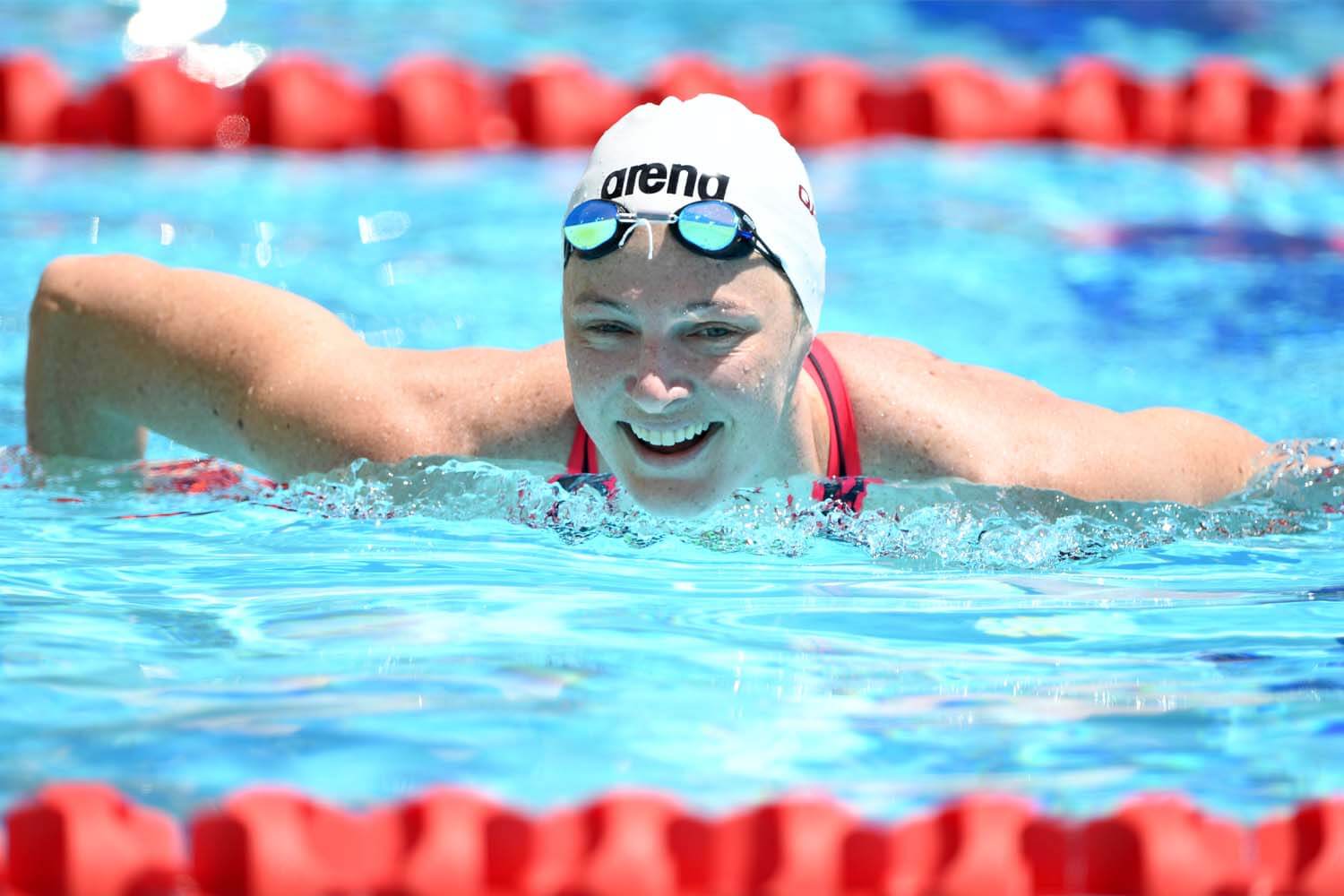

Simone Manuel and Cate Campbell at Pan Pacs — Photo Courtesy: Delly Carr/Swimming Australia

Campbell admits that like most human beings, she likes being praised. She assumed that she was liked for her abilities in the pool—and the medals she won for Australia—so her ability to perform became her measuring stick. So after the Olympics, she considered herself a failure. Everywhere she looked, she saw criticism of her performances and even of her personally.

“Anyone with a mobile phone and a Twitter or Instagram or Facebook account can add their comments, whether they should be commenting or not,” Campbell said.

Finally, after reading about her Rio collapse over and over for two years, she decided to speak up. In early September, Campbell published a note on the website “Exclusive Insight” aimed at a group she called “keyboard warriors.” Why had this faceless, anonymous group come after her? Campbell called it “Tall Poppy Syndrome”—that is, “when a poppy pops its head above the rest, it’s fair game, and you want it to be brought down.”

In Campbell’s eyes, sports fans are inspired by underdog success stories, but once consistent excellence is established, jealousy kicks in.

“Instead of being inspired by them and going up to their level, you take any opportunity to bring them back down to your level,” Campbell said. “At the slightest stumble, you’re like, ‘Ahh, they’re not that great. I’m going to bring them back down to my level.’ It’s easier to bring somebody down than to push yourself and motivate yourself to be better.”

So Campbell penned her letter to convince not only others but also herself that she actually deserved some credit for what happened at the Olympics.

“It was coming to grips with the idea that just because at one moment in time you didn’t stand up and live up to everyone’s expectations,” she said. “That doesn’t make you a failure. I think that more than anything else, it was me coming to the facts that, ‘Yeah, I didn’t perform the way that I wanted to, but I still had merit, just because I went and tried.’”

***

After the Olympics, Campbell had to remind herself that no one wins forever, in any sport. So with that in mind, why should she attach so much of her self-worth to the digits that showed up on the scoreboard at the end of a race?

“I had to learn to go back and see qualities in myself that I’d never had to look for before. ‘Who was I worth?’ and ‘Was I worth something outside of the swimming pool?’” Campbell said. “If I attach my self-worth and identity to something that isn’t lost in hundredths or tenths of a second, that is enduring.”

As Campbell became one of the world’s top sprinters and then spent nearly a decade in that position, she became aware—too aware, perhaps—of how much her races meant to Australia and to her sponsors. She began to fear competition and worry about the results instead of reveling in whatever challenge the race posed. She would spend too much time thinking about her competition and become intimidated.

But finally, Campbell realized that it’s easier and more enjoyable to stand behind the blocks without worrying about any of that. Campbell knows that whatever time she swims, whatever medal she wins, none of that will affect how she feels about herself when she leaves the pool at the end of the night.

Photo Courtesy: Delly Carr/Swimming Australia Ltd.

So that was her plan of attack at Pan Pacs: Don’t worry about what anyone else will do (including American rival Simone Manuel, who Campbell called “one of the most impressive specimens to ever walk this Earth”). Have perspective. Think about what makes swimming, even after 11 years of racing on the international circuit, seem so exhilarating.

“It’s always been that one thing that I’ve seen a really direct correlation between hard work and results,” she said. “It’s seeing how much better you can be, how much harder you can push, that I find really exciting, even still.”

Today, the primary reason Cate Campbell is still swimming is not to win an individual Olympic gold medal. Yes, she would love to win one, to add to her collection of two relay golds, but she now knows she could live without one. There’s more to her life. Right now, in fact, swimming is just a small piece of her daily routine.

After Pan Pacs, Campbell resisted the urge to jump back into training while she carried all her momentum from Pan Pacs. Instead, she has been swimming just two to three times per week, with an additional two to three gym sessions. Meanwhile, she has gotten her first taste of the working world—an experience in the communications department at the Queensland Rugby Union.

The instincts of an elite swimmer point against taking an extended break, particularly with less than two years before an Olympics, but Campbell knows that right now, patience is a must. She took a hiatus a year ago, skipping the 2017 World Championships, and she came back in all-time best form at Pan Pacs. A perceived lack of fitness one day doesn’t mean it’s worth scrapping her carefully-constructed plan.

Towards the end of 2018, she will ramp up her training again, with an eye on the 2019 World Championships and the 2020 Olympics—which would be Campbell’s fourth and she insists her last. But still, she won’t be all-in right away—that’s the plan she and longtime coach Simon Cusack agreed to with eyes on the long-term.

“For me, it’s about having good life balance—keeping busy outside of the swimming pool,” Campbell said. “It’s about doing things on the weekend that I enjoy, like hiking or kayaking or anything that’s outdoors, and allowing myself to go and do those things with the knowledge that on Monday morning, I am going to be a little bit tired and a little bit sore, but that’s okay.

“Obviously, when it is closer to competition time, that is when I probably cut back on those things and focus more on swimming.”

In January, she will move away from Brisbane for the first time—a move she insists would have happened years ago if not for swimming—as she follows Cusack to Sydney. There, she will train for one final long-term goal, a goal not as simple as one particular result in 2020.

Sure, she would love to make another individual Olympic final or two, but the actual results of those Olympics won’t feel as important to Campbell. She won’t let success or failure be judged on races lasting less than a minute.

“I now know that that I can be content without an individual Olympic gold medal, having been in the position where it was probably most likely to happen, and it hasn’t,” Campbell said. “I know that life goes on, and I’m perfectly content without it. I think it’s about being in the best shape, in the best frame of mind and in the best physical shape possible for 2020 and really allowing myself to enjoy it.”

Facts, not keyboard warrior opinions:

1. She was only third in the world, to Sjostrom and Blume, in the 50 LCM Free this year, one of her two primary swimming events for our country.

2. She does not mention her teammates, family, or (sometimes faster) swimming sister in the article. She uses the words “I” or “me” or “myself” dozens of times while expressing self-pity over past swim performances and her life.

3. She spoke derogatorily of the U.S. swim team following Pan Pacs,despite the fact that she finally swam her only good 100m Free swims in years, and the U.S. team won a dozen more gold medals than Australia. She expresses no regrets about that here, or elsewhere.

4. Though born in Malawi, she swims for a country where some athletes recently dressed in Blackface to mock Serena Williams, yet she terms the African-American woman who beat her at the 2016 Olympics not a champion or a great person or a great swimmer, but a “specimen” who “walk(s) this Earth.”

5. She then is puzzled as to why she is not liked on social media, blaming it on “Giant Poppy” syndrome or “keyboard warriors.”