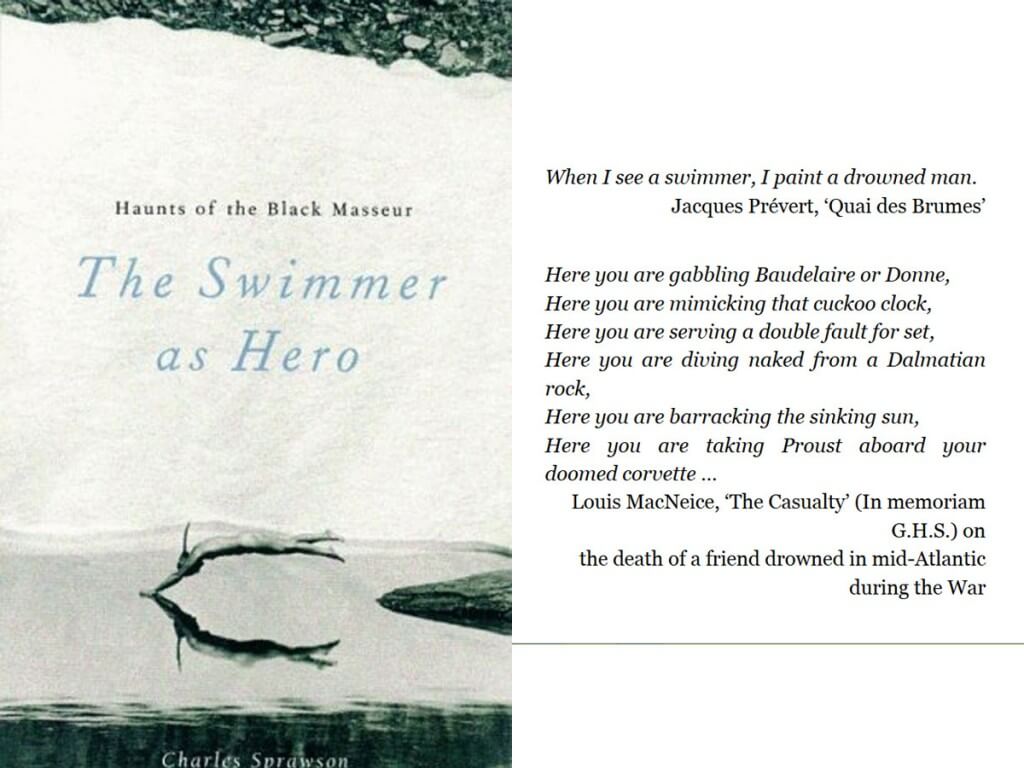

“Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer As Hero” — A Book That Changed My Life

Commentary by Casey Barrett, reposted by permission from CapAndGoggles.com

I picked up Charles Sprawson’s book Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer As Hero while wandering a used bookstore outside of Dallas in 1998. The title made no sense to me, but the subtitle certainly did. Especially at the ego-drenched age of 23, before careers began and humility gets forced upon you when you realize that no one cares about your pool-bound exploits. The swimmer as hero, indeed. I could relate to that. Swimmers, particularly those who’ve stood atop podiums, are not lacking in self-regard.

I took it home and opened it up and waited for it to confirm all my heroic impulses. It didn’t. Instead, I found a deep scholarly look at the true character of swimmers – isolated souls that somehow find fulfillment in a lonely sensory-deprived act. In his introduction, the author writes that, at a young age, he formed “a vague conception of the swimmer as someone rather remote and divorced from everyday life, devoted to a mode of exercise where most of the body remains submerged and self-absorbed. It seemed to me that it appealed to the introverted and eccentric, individualists involved in a mental world of their own.” OK, guilty as charged, I thought.

The author, Charles Sprawson, is an Englishman raised in India, educated at Trinity College in Ireland, and by profession, an art dealer with a focus in 19th century paintings. On the book jacket he also calls himself “an obsessional swimmer and diver who has swum the Hellespont.” The Hellespont? For those Americans, from the newer side of the Atlantic pond, you’re forgiven if this doesn’t resonate. It does for the Euros. If the English Channel remains the most iconic of all open water swims, the Hellespont must be the swim most steeped in literary significance.

On May 3, 1810, the poet Lord Byron swam the four-mile strait in Turkey that connects Europe to Asia. Byron was 22 at the time, a struggling poet traveling Europe. His swim was done in honor of the Greek legend, Leander, a romantic swimmer soul who, according to mythology, would swim across the stretch each night to visit his lover, Hero. The fair Hero would light a lamp in her tower to guide him, until one stormy night when the winds blew out her light and Leander lost his way and drowned in the waves. When Hero learned his fate, she tossed herself from her tower into the sea to be with him in death. Call it Romeo & Juliet, Swimmer Edition. In any case, Lord Byron loved that legend enough to emulate the doomed Leander. And the poems it inspired helped sweep Byron to literary immortality.

If your knowledge of swimming history only goes back to 1896, or 1996 for that matter, this book will pull you a lot further back into the currents of our sport. You’ll learn that, for the Romans, the definition of ignorance was a man that “neither knows how to read or swim.” You’ll also learn that while the Romans were big on swimming and their Bathhouses, “the more degenerate the emperor, the more sumptuous tended to be his Baths.”

Sprawson travels the world of pools, rivers, lakes, and oceans, searching for “that peculiar psychology of the swimmer, and his ‘feel for the water.’” He’s English, so his focus remains rooted in the UK tradition, but the book’s finest section is the one called, rather ambitiously, “The American Dream.”

The book was first released in 1992, so you’ll find no passages on Michael Phelps or any athlete from our “modern times.” You won’t even find anything on Mark Spitz. There’s a bit on the incomparable Duke Kahanamoku and Johnny Weissmuller, along with America’s original swimming siren Eleanor Holm – the hard-partying backstroke badass who was thrown off the U.S. team on the way to the 1936 Olympics in Berlin because she was tipping back the champagne on the Games-bound boat across the Atlantic alongside the assembled sporting press. Holm was the 1932 Olympic champ in the 100 back and the world record holder, but instead of defending her gold she spent the Berlin Games flirting with Nazis and partying like a Weimar flapper.

Olympic exploits and scandals aside, Sprawson is more interested in how our sport has filtered into our creative, literary consciousness. There’s John Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” a sort of suburban angst update of the legend of Rip Van Winkle. There’s F. Scott Fitzgerald and his gin-soaked observation that “all good writing is swimming underwater and holding your breath.” There’s Tennessee Williams and the Southern gothic tradition where “those attracted to water tend to be dreamers, outcasts, the ‘fugitive kind’ who by temperament, character, or birth are fated to be anachronisms trapped in a world ‘lit by lightning.’” And there’s the observation that Hollywood has captured time and again that “These sapphire pools, liquid emanations of the American Dream, sought-after status symbols, emblems of material success, became for some a means of escape from the contamination of a corrupt society.”

But best of all, there’s this piece of dark wisdom from Baltimore’s most immortal citizen, Edgar Allan Poe. In an essay called “The Imp of the Perverse,” the sharp and cynical-eyed Poe summed up a base instinct in all of us. He wrote: “There is no passion in nature so demonically impatient as that of him who, shuddering on the edge of a precipice, thus meditates a plunge.”

I’ve been dwelling on that line for 17 years, recalling countless workouts, staring at the still water before warm-up. And the countless times since, when the only way to move forward is to plunge ahead.

Haunts of the Black Masseur is available on Amazon.