Harry Hauck: Polo Pirate of the Caribbean

Editor’s Note: erroneous reports out of Puerto Rico said that Harry Hauck, considered by most to be the grandfather of water polo on the island, had passed away after a lengthy illness. Swimming World inadvertently published an obituary to this effect. In fact, Coach Hauck is alive and—even though his health is not great—still with us. Following is an interview done with him in May 2020.

Despite reports to the contrary, Harry Hauck, one of the most important people in Puerto Rican water polo history, has not cleared out from the locker room of life.

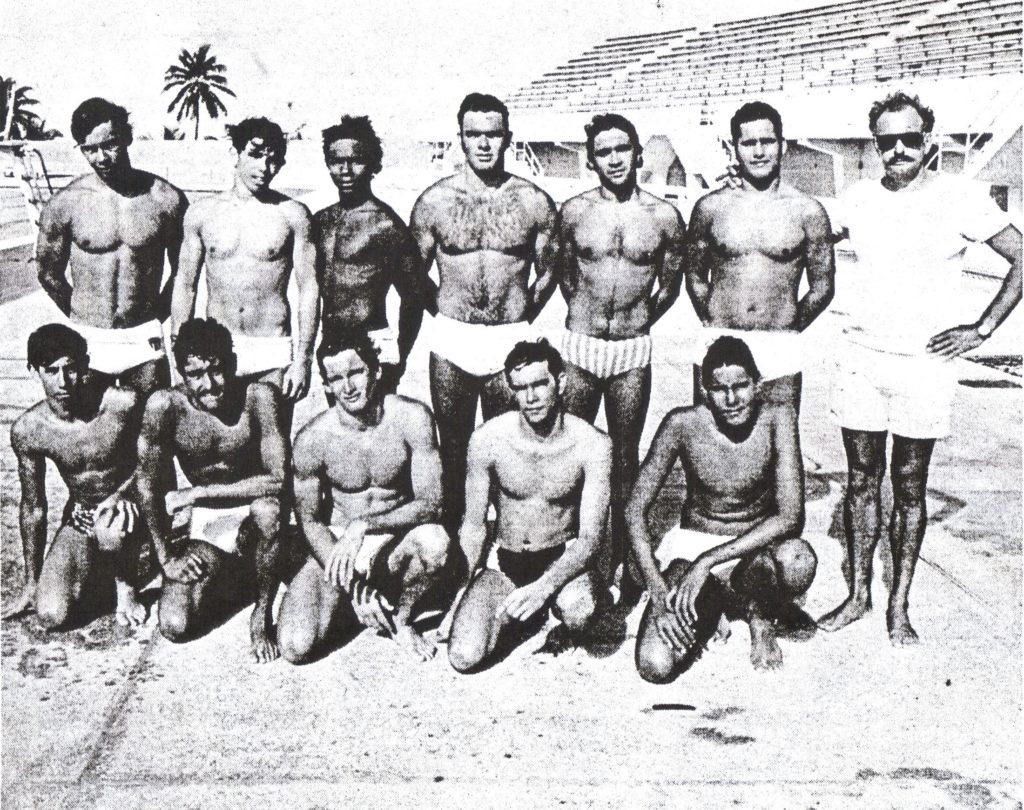

Photo Courtesy: Harry Hauck

As many have attested—from Manuel de Jesus, a long-time coach and official in Puerto Rico, to Carlos Steffens, arguably the best polo player the island ever produced—Hauck is one of a kind, a Puerto Rican “living legend” who, upon his arrival in 1964 was responsible for launching the country’s national team program. If this was his only accomplishment, Hauck’s achievements might not be so grand, his legend not so large.

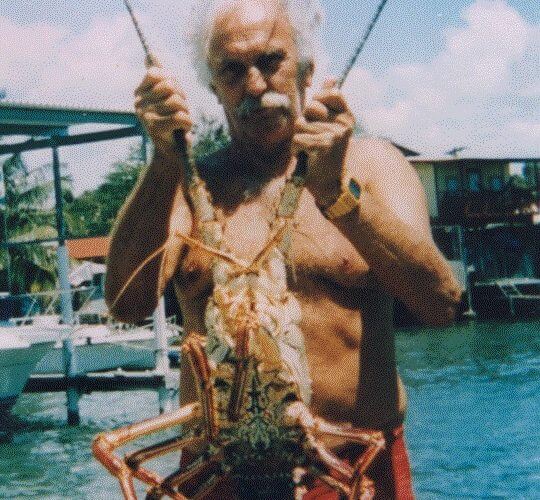

A tireless worker for aquatic success both in his native Michigan and in his adopted home pf Puerto Rico, the swimmer turned Navy frogman, turned coach, turned scuba diver extraordinaire sustained both a national water polo program and a rewarding career in open water swimming, one which took him and his family all over the world.

Following is a transcript of the unvarnished Harry Hauck: his time in Detroit as a swimmer, polo player and coach; his stint with the U.S. Navy during the Korean War; his flight to Puerto Rico where he built a viable national team from scratch; his connection to the 1979 Puerto Rican team—considered to be the island’s best ever—and numerous open water swim exploits.

***

– You said that you are from Detroit with strong connections to swimming and aquatics. How did you get involved with water polo?

I was the only water polo player in the world that was a bonafide member of a water polo team and couldn’t swim a stroke.

– What do you mean you couldn’t swim a stroke?

I could not swim. I had some friends, neighborhood buddies. I used to go down to the local recreation center in Detroit, which had a water polo chairman within the recreation department. At the end of adult swimming, all the swimmers would leave and the water polo team would practice.

I would sit in the balcony and watch them practice. And this was a 25-yard pool, so the shallow end had a big goal. one night I was sitting there watching and the coach hollered up: Hey, we’re short a man, come on down and play goalie in the shallow end.

That’s how I did it. He gave me a membership card to a men’s water polo team. And I couldn’t swim in the deep end.

– But you learned how to swim.

I taught myself.

– Detroit is not known as a polo mecca. Where in the city did this happen?

The St. Clair Recreation Center was [on] the East Side. I ended up on the water polo team. Two years later, I earned my varsity letter swimming for Wayne State University (in 1947).

They didn’t have [a water polo team] when I was there, but they got one later. I ended up as a Navy frogman, three years after I learned to swim.

– How did you go from Wayne State to Navy frogman?

The Korean War [was on] and I enlisted. I had seen the movie about the frogmen. I went through and was accepted. I made it through hell week and was in Team 2 on the East Coast. I was in the Navy from ‘51 to ’55. Once the Korean War was over, I got out.

– The Frogmen are the precursors of the Navy SEALS, right? What sort of training did you do?

Demolition was very prominent in the Pacific. When the U S was patching together all those islands so we could bomb Japan. Once the Second World War ended, they broke up the teams. When Korea started, they reactivated them.

I was one of the early ones activated. It turned out that there was no amphibious warfare in Korea. So, they started doing inland excursions. And that’s how SEALS were born.

– You didn’t go to Korea?

The West Coast had Teams One, Three and Five. The East Coast had Two and Four—and Two and Four were doing all the experimental work. We were in Europe. I dove in Greenland. I did night sneak attacks in Guantanamo Bay.

– You left the Navy in 1955.

When people introduce me as a SEAL, I jump all over them. I said: I was never a SEAL. I came before the SEALS, and they take umbrage with saying you’re a SEAL and you weren’t.

I went to Puerto Rico in 1952 with the Navy. After my UDT (Underwater Demolition Training), I was an instructor in the next class. I came down here as a program instructor and I put through the winter class at the Navy base in [Roosevelt Roads], Puerto Rico. I fell in love with the island. When I got out, I went back to Detroit, met my wife, got married, had kids, graduated from college.

I went back to work for the recreation department. I always had one foot in the islands. In 1964, the US Olympic team with training in California, I had a swimmer on [the team]. And I went out to watch. A guy who ran Swimming World magazine at that time [Peter Daland] put an ad in the magazine for me. I got a phone call from the Caribe Hilton. They said: Do you want to come to Puerto Rico? I didn’t know what the hell was going on. I had a wife and two kids.

So, I burned all my bridges and came down here.

– What was Puerto Rico like when you arrived in 1964?

In ‘52 we were down south at the Navy base and I came up to San Juan a couple of times on liberty. But I didn’t get a feel for the island until I moved down here. Things were just starting to change. The pharmaceutical companies had moved down here on a tax-free deal. And they were hiring a lot of local people and there was a middle-income group created in that period of time.

Caribe Hilton. Photo Courtesy: Hilton Hotels

Before that it was just the rich and the poor.

– Did you start a swim team there?

No. There was a half-a-dozen age group and senior swim teams at the various clubs. The Navy had a team and the Army, too. I came to work at the Hilton and worked there for a while.

There was a guy who was selling scuba trips. Of course, I did that in the Navy. When I quit coaching, I went into business teaching diving. I was an instructor for 44 years.

– Was there any water polo on the island when you arrived?

Nothing! When I lived in the States, the coaches ran the sport. Except when it was an Olympic year. When I moved to Puerto Rico, we were part of FINA. So, the coaches had nothing to say; the civilians ran things. I locked arms with them, and they told me: You go ahead and start the sport, but we’re gonna run it.

That’s basically what happened. I got a team together. We used volleyballs, women’s bathing caps, and put together two teams. And we had a newspaper come and take pictures. And that was the first water polo on the island.

– Do you remember the date?

1965.

– And you had two teams that competed.

They were all my players. You’ve got to remember that, if you’re a track coach, you can move to a country and get a couple of guys to run and jump. If you have a stopwatch you’re in business.

A team sport, like water polo, first, you have to find 11 guys who can swim well and then you have to have goals and caps and balls. They’ve got to learn the rules. And then you got to teach all the officials how to time and keeps score.

And then you got to have somebody to play against.

– There weren’t any referees in Puerto Rico.

Nobody. I taught everybody.

– Carlos Steffens talks about how the New York Athletic Club came to Puerto Rico for an invitational. What do you know about this?

We created a Christmas tournament. I talked the association into holding a water polo tournament at Christmas time. We got the New York AC. we got, a couple of teams from California, they were junior colleges. A team from Switzerland came. That’s when coaches from California came and started recruiting players from Puerto Rico.

You’ve got to remember, I started a sport on an island where there were no water polo players. We played amongst ourselves on clubs that didn’t know what they were doing. And they were standing on the bottom all the time and catching the ball with two hands.

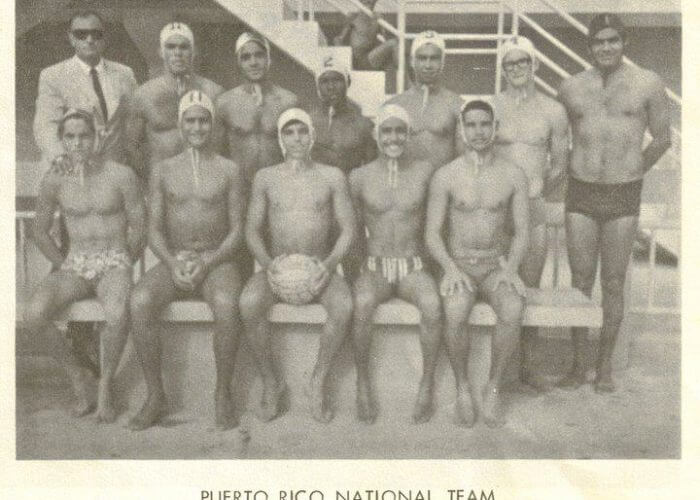

Photo Courtesy: Edwin Purcell

We had the Central American games, which is second only to the Pan Ams in that part of the world. There were teams left over from the old British dynasty. We had Jamaica and Trinidad and the Bahamas. They came for the tournament and we became friends.

There was an age group swimming tournament held in Jamaica. I took a team there, and the Jamaican players were all older guys, but they helped train my guys because they had no one to learn from. From there they got better and better.

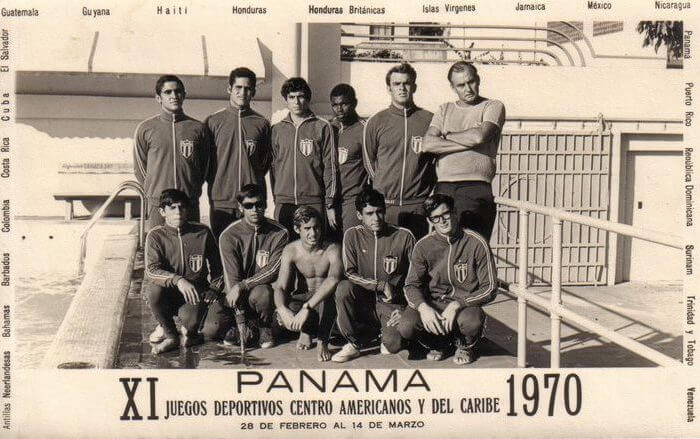

When we went to the senior Central American Games in Panama [in 1970], that was a tryout for the Pan Ams. We had to finish in the top six from this part of the world, and we finished sixth on the last day, So, we were able to go.

– Was 1971 the first time that Puerto Rico ever sent a men’s water polo team to the Pan American Games.

Correct. They were held in Colombia.

– Miguel Rivera, who was on the 1971 team, spoke highly of his relationship with you.

I was going to swim the [English] Channel with my youngest son, and then come back and again with my whole family and swim a relay. So, I took him to England with me.

[Miguel Rivera and the Fantastic, Unbelievable and True Story of Pitt Water Polo and Puerto Rico]

I trained in a walk-in freezer and the veteran’s hospital. I got Miguel a grant because we used a freezing room and some hospital facility. He wrote a paper about cold water and senior citizens swimming.

– One of the things that Carlos Steffens and Miguel Rivera mentioned was that you used any technique possible for training.

We were in shape. We weren’t very skillful but we were in shape.

I had them wear sweatshirts and weight belts—and had seven of those guys play against seven who didn’t have that. That made the guys in weights stronger and faster, they tended to play from behind against what the other half was wearing. It got to the point where you had to shoot more, otherwise you drown with the weights on.

– What’s compelling is, you come to the island in 1964; in 1966 Puerto Rico hosts the Central American and Caribbean Games, and by 1971, you’re leading a team to the Pan American Games—the first time ever for a Puerto Rican team to compete in the region’s top competition.

I went to a Copa America Games in March for the opening ceremony, the pageantry was great. When I went to the Pan Am Games it wasn’t the first time. What was interesting to me was the U.S. was deadly rivals of the Cubans, so when I got there, the U.S. coaches looked down their noses at me. “Who was this clown?”

Ted Newland thought a Latin was running this team. It was me and they didn’t know who I was.

[Passages: Ted Newland, Coach Emeritus of UC Irvine Men’s Water Polo, Passes Away at 91]

Photo Courtesy: Edwin Purcell

So, we’re sitting there, and [Newland] said: You’re gonna vote with us when it’s time to vote. Because I knew all the Cuban coaches from playing against them. I said: You know what? You’ve got five guys [on your staff] and I’m alone here. You got one vote and I’ve got one vote.

I’m just as good as you are.

For me, that was the success of the Pan Americans, that I was able to sit at a table with the so-called California trust.

– Given their proximity, Cuba was an important rival for Puerto Rican water polo. But the Cold War was in effect.

In ’69, the aquatic age group games were held in Havana. I coached the U15 and U17 team there. That was quite a deal because we flew to Havana and I had three children on the team. My sons [Harry Jr. and Timothy] played polo and my daughter [Krista] swam.

Our passports allowed for one round—we were allowed to go there and then come back.

We stayed in a hotel called Habana Libre which was the old Hilton. We had two floors and there wasn’t much to see, and a lot of security. I had a sportswriter call me from San Juan, and I could hear that my phone was tapped.

I was assigned a guide for myself and my 11 players, anywhere we went. We had a place where we could practice once a day. It was a club on the waterfront. We got there a little bit early and the Mexicans were training. I crossed the street and looked out at the ocean. The guide came along and I said: Any chance I can go diving while I’m here.

He said: Oh no, no. You were here in 1954 with the Navy.

I almost fell off the step!

Hauck (far left) and the 1971 national team. Photo Courtesy: Edwin Purcell

We were told by the state department, don’t take anything over there, don’t talk to anybody. [Before we left] I got phone calls from all kinds of people—Cubans—[who would say]: My cousin’s still there, my brother’s still there, would you mind taking this over?

I ended up with a couple of extra suitcases of medical supplies; I asked the people: How will I know who’s who? They’ll come to you, they answered.

When we got ready to go back to Puerto Rico, an old man came [to the hotel]—he was white haired—and I got into the elevator with him alone. I said: I’ve got two suitcases full of stuff. He looked at me and then went in the elevator to the top floor and I gave it to him.

– The core of the 1979 team all started training with you earlier in the decade. Yet you’re were watching from afar because the Puerto Rican Swimming Federation had installed Fernando Salabarría as head coach in 1972.

The association wouldn’t even invite me [in 1979]. I watched part of a game on TV, and the announcers called Salabarría the guy who brought water polo to Puerto Rico. That just rubbed me the wrong way. We’d moved aggressively to play the game and to qualify for Pan Ams—we were just about ready to break loose and do something when ’71 came. And they bounced me out.

That’s left a bitter taste in my mouth over the years.

There was always a little bit of conflict between water polo and swimming. In ’66 I had gotten enough polo players—enough guys to know the rules, handle the ball. They had some background, so when the time came for the ’66 games, I put forth the names of eleven players. The swimming association said: No, no! Four of them are gonna swim, they can’t play polo.

– But, you were part of the whole story; you are mentioned frequently as the originator of polo on the island. You must have a sense of ownership about what happened with polo in Puerto Rico.

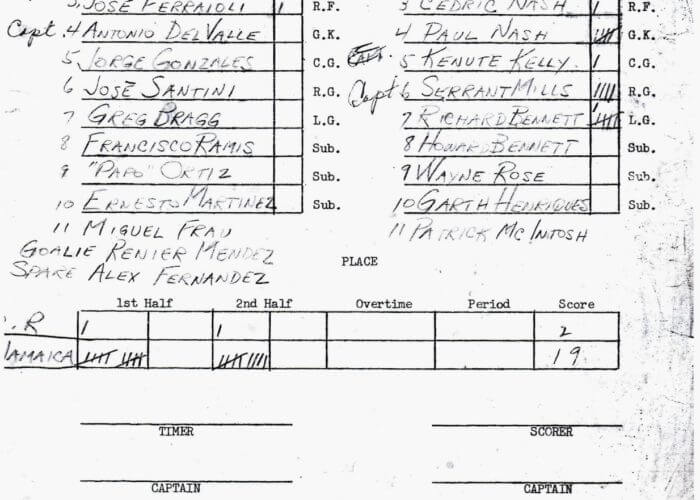

I don’t know what’s happening with polo on the island. One of my original polo players [Antonio Del Valle] became a doctor. He ended up at the University of Puerto Rico. He’s still and MD but he ran the water polo team at University of Puerto Rico—he was the athletic director over there.

1965 score sheet, Puerto Rico vs. Jamaica

He tried to start beach water polo, like beach volleyball.

He kind of keeps me updated but at one point in time we had a water polo league. We had a 12 and under, a 13, a 15 and a senior—we had three different age groups and we actually had a league. One weekend, the games would be in San Juan, the next weekend they would be in Mayagüez, then we’d be in [Ponce].

They had a lot of games going on all the time. And I don’t know what happened; I haven’t heard anything.

When the fiftieth year came around [in 2015], I called Del Valle [and said]: Look, it’s 50 years, we have to have some kind of commemoration. He put together a little tournament for the anniversary, and my second son [Timothy] came with a team from Miami and won second place.

– On an island with 3.2 million inhabitants, you mentioned that only 25% can swim. Doesn’t that seem unusual?

My aquatic life started in a recreation center. Every recreation center had a swimming program. They’d open up the pool at 2 in the afternoon and close them at 10 at night. During that time, you would have team swim, adult swim, women’s night—but you’d also gave swimming lessons. And a swimming team and a water polo team.

I’d go to work with a foot of snow falling, and it’d be 100º in the pool.

It’s hard to understand in a climate like you have here, why people don’t swim. In places like Detroit, Chicago, New York, people swim all winter long and they’re public pools.

Given Puerto Rico’s weather and great swimming tradition, you think there would be more involvement with the water.

When the ’66 games came around, I was surprised there were water polo teams from the Bahamas, Trinidad, Jamaica, the British Islands. Apparently, they played water polo in their Commonwealth Games.

– You made an impressive break from the States. What is the best memory that comes to mind from a lifetime in Puerto Rico?

Over the years I started taking my scuba students to the beach for dives and making them bring back solid waste. I did 200 of those beach clean-ups. I got a bunch of awards from the island. The diving industry gave me an award for that.

Hauck and the 1970 CACG squad.

I’ve done long-distance swimming. I swam non-stop from St. Thomas to Puerto Rico when I was 55 years old for 30 hours to raise awareness of senior citizen fitness. And I swam the English Channel with my family—a mother, father, and four kids. That was to raise awareness of family togetherness.

The last thing I did was a 24 hours swim in the ocean for AIDS awareness as every 24 hours, four people died from AIDS in Puerto Rico. So, I swam non-stop at a beach front for 24 hours.

All the long-distance swims I did—I never made a dime on any of them. One of them took thirty days and I used my own vacation time. There used to be a radio program here called “Living Legends.” They’d start on a Monday and say two things about a person, then [more] on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday. On Friday, they’d wrap it all up and spend the whole hour [on the person].

I was one of those living legends. [Sometimes] I’d meet someone and they’d say: Mr. Hauck – living legend!

I’m a legend here in Puerto Rico; if I go someplace else, I’m nobody. I lived here 54 years.

My life has been aquatics; I worked in a pool before I went in the Navy. I was in a bathing suit all the time I was in the Navy.

My whole life has basically been in a bathing suit—and Puerto Rico’s got the right attitude for me.

Conozco a LA familia. Lamento LA muerte de ambos.