Happy Anniversary: 48 Years Since Mark Spitz Went 7-For-7 at Munich Games

Happy Anniversary: 48 Years Since Mark Spitz Went 7-For-7 at Munich Games

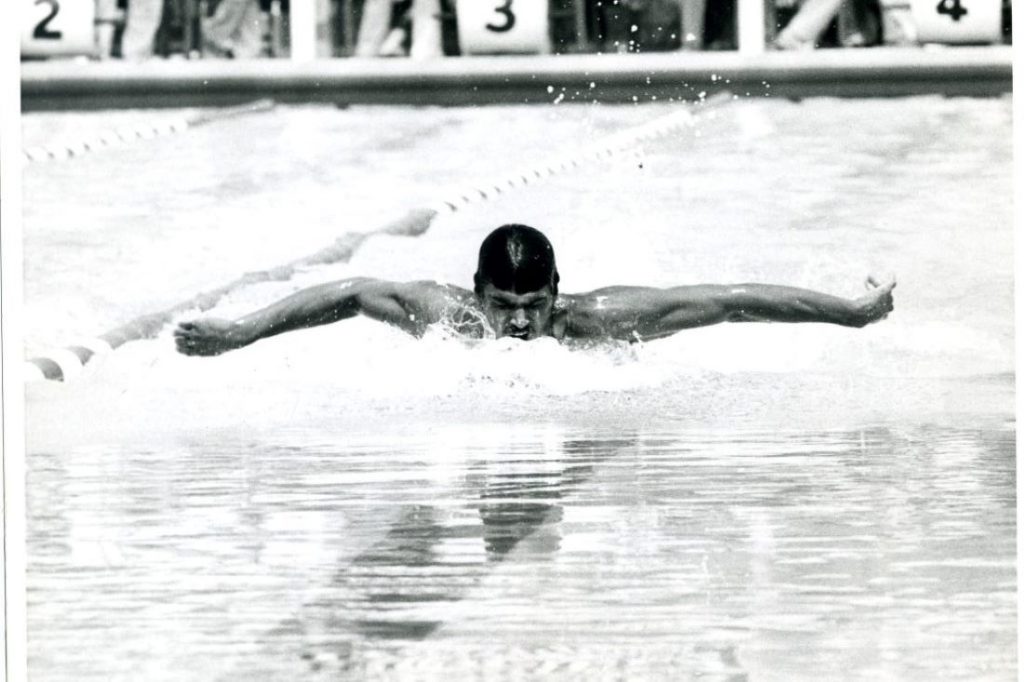

Today, Sept. 4, 2020, marks the 48th anniversary of Mark Spitz’s seventh gold medal of the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. Each of Spitz’s titles was won in world-record time, and the accomplishment became the sport’s measuring stick for greatness for more than three decades. The following piece takes a look at Spitz’s march to Olympic glory.

***********************

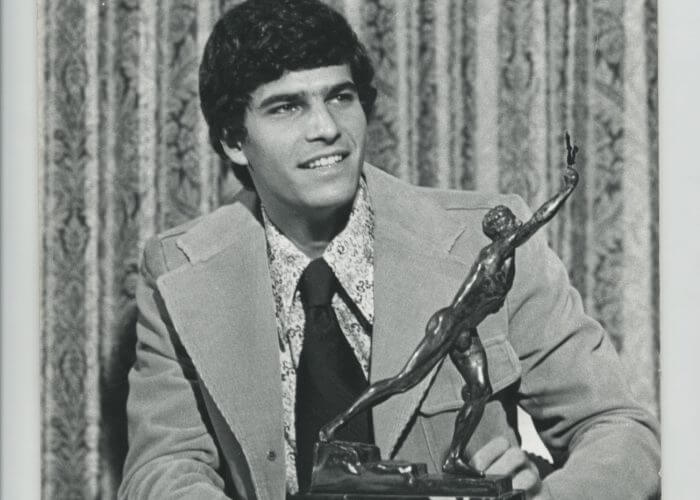

The mustache. The confident look. The chiseled physique. All are standout characteristics of Mark Spitz. Once among the most revered athletes on the planet, Spitz remains an iconic figure in the sporting world. Even today, nearly a half-century after he emerged as the star attraction at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Spitz’s image is easily identifiable.

Success at the Olympic Games can make a career, forever defining an athlete. It’s why the mere mention of Jesse, Nadia and Carl means Owens, Comaneci and Lewis. But what Mark Spitz accomplished in Munich was entirely different from anything seen before, and why he stood alone on an Olympic pedestal until a fellow swimmer came along and knocked him off his lofty perch.

For one week, Spitz could do nothing wrong. He competed in seven finals at the1972 Games and won seven gold medals, none of the events featuring much of a scare. All seven of his victories arrived in world-record time and Spitz left West Germany as a legend and for a whirlwind tour which celebrated his thrilling performance. Truthfully, Spitz accomplished what many expected, but it was also a measure of redemption for what took place four years earlier in Mexico City.

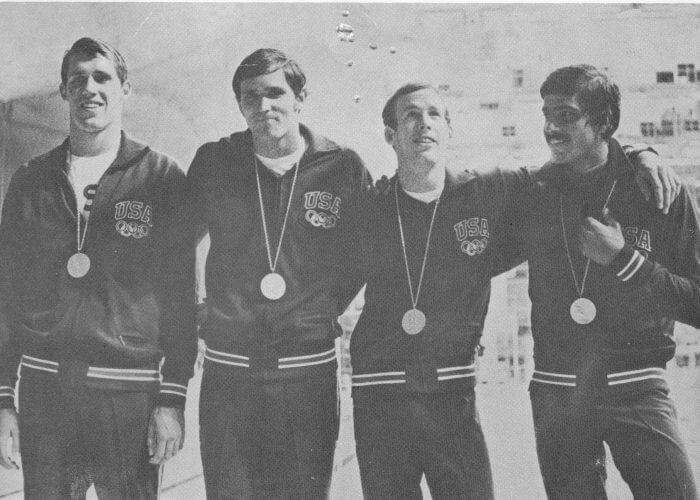

Photo Courtesy: ISHOF Archives

On the surface, the two gold medals, one silver and one bronze Spitz won at the 1968 Games seem like a success. After all, few athletes leave an Olympiad with four medals. But there were much higher expectations for Spitz, both from outside sources and on a personal level. As a multi-time world-record setter, Spitz brashly predicted he would win six gold medals in his first Olympiad. He fell shy of his forecast.

While Spitz won gold medals as a member of the United States’ 400 freestyle relay and 800 freestyle relay, he came up short elsewhere. As the world-record holder in the 100 butterfly, Spitz took the silver medal behind American teammate Doug Russell, a setback which also denied Spitz a place on the 400 medley relay, which went on to win the gold medal. Spitz also “settled” for the bronze medal in the 100 freestyle, an event in which he became the world-record holder by 1970.

The biggest disappointment of Spitz’s Olympiad unfolded in the 200 butterfly. Entering the 1968 Olympics, Spitz had twice set the world record in the event and was viewed as unbeatable in what is one of the sport’s most grueling events. But Spitz flopped in the final. As teammates Carl Robie and John Ferris picked up the gold and bronze medals, Spitz finished last, almost two seconds behind the seventh-place finisher and an inexplicable eight seconds off his world-record time.

“I had a difficult time from the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City where I was expected to win a lot of gold medals,” Spitz said. “And if I just look at my performance of winning two gold, a silver and a bronze, I mean that is pretty remarkable. But the problem was, is that I didn’t win a gold medal in two events I held a world record in. And that was just the reason that I basically had this fire in my system to be able to want to actually go for another four years. I found it kind of difficult to work out and train. But I had a focus and the focus was to do the best I could.”

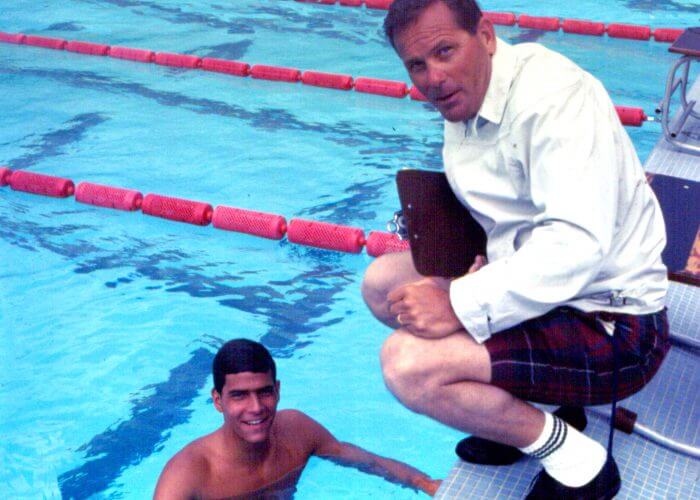

If there was any doubt whether Spitz would bounce back following his Mexico City struggles, they were quickly answered. Originally coached by Sherm Chavoor of the Arden Hills Swim Club in California, Spitz joined forces with legendary coach James “Doc” Counsilman when he enrolled at Indiana University following the 1968 Games. As a member of a Hoosiers squad stacked with talent, Spitz didn’t waste much time returning to form, setting world records over several disciplines. A key was Counsilman restoring confidence in Spitz.

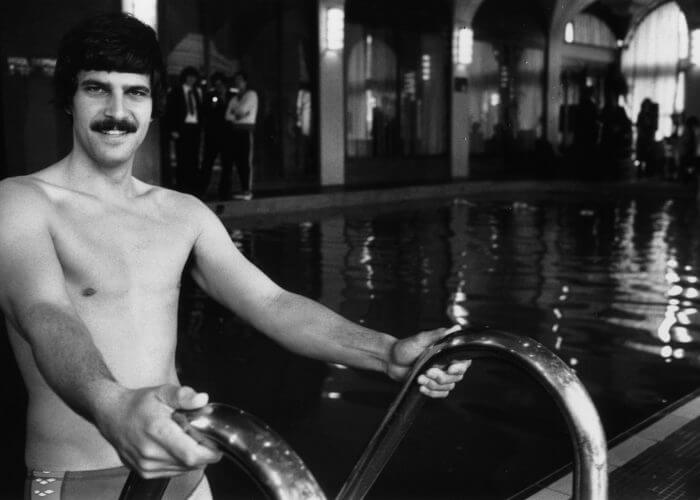

Photo Courtesy: ISHOF Archives

As he guided Indiana to NCAA team championships, Spitz shifted his focus to the 1972 Games in Munich and atoning for what took place in Mexico City. He studied his competition and adopted a mentality of invincibility, a different approach than what he took into the 1968 Games as a cocky 18-year-old. This time around, Spitz looked at each event on an individual basis, not caught up in the overall medal haul. If he took care of business event-by-event, the sum would be what he envisioned as possible.

“I think what a true champion has is the ability to be able to know his competitors and everything about his competition, and then try to make one or two less mistakes than those he competes against,” Spitz said. “And on a regular basis that they do that, quantitatively saying is that that he may have only been four or five percent better than anybody, but since it was always four or five percent better than anybody, the illusion was he was so grand, and that’s what makes a great champion.

“And (then) they’re able to repeat that time and again, regardless of the conditions. Because not every time you come to a swimming pool do you feel great, or if you’re in track and field, not every time you hit that track you feel good. Or in boxing, I knew Muhammed Ali. There were a lot of times that he felt terrible. But he knew he had to rise to the occasion. And they did.”

Spitz knows the feeling.

If there was any lingering doubt attached to his performance from the 1968 Olympics, Spitz put that notion to rest with immediacy. His first event in Munich was the 200 butterfly, the discipline which produced his last-place finish from four years earlier. Really, it was the perfect way for Spitz to erase any demons.

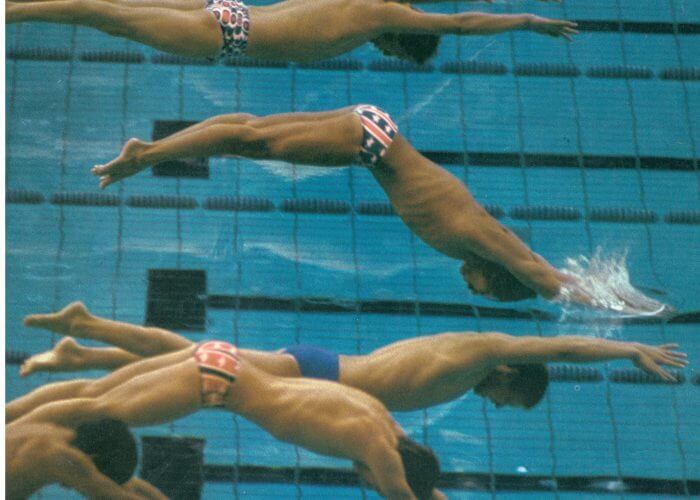

Climbing the blocks on August 28 as the world-record holder, as was the case in 1968, Spitz didn’t have any trouble this time around. He bolted to the front of the field and buried his competition behind a world-record time of 2:00.70. The United States swept the medals, but silver medalist Gary Hall (2:02.86) and bronze medalist Robin Backhaus (2:03.23) may as well have competed in a different race. About 40 minutes later, Spitz added his second gold medal and world record when he anchored a squad of David Edgar, John Murphy and Jerry Heidenreich to a three-second rout of the Soviet Union in the 400 freestyle relay.

Photo Courtesy: ISHOF Archives

As Spitz started his Olympic program, he was equally known for the mustache he refused to shave. While other athletes were intent on shaving all hair from their bodies, Spitz went for an anti-swimmer look, not concerned that the facial hair would cost him a few hundredths of a second here or a few hundredths of a second there. The mustache also proved to be an advantage from a mental standpoint as his competition was consumed with its presence. Several swimmers from the Soviet Union asked Spitz whether it slowed him down. A year later, after they saw what Spitz accomplished, many of the Soviet swimmers sported mustaches of their own.

“I grew that mustache out of spite because my college coach said you need to look like the all-American boy,” Spitz said. “It took me about five or six months to grow that mustache. I went to the Olympic Trials and had intentions of shaving it off. All my competitors in the press were talking about it. I go, ‘Wow, they’re not figuring out how to beat me. I might as well keep this thing.'”

His first two victories supplying momentum, Spitz secured his third gold medal with a victory in the 200 freestyle, overhauling teammate Steve Genter in the latter stages of the race and via a world-record effort. Standing on the podium to receive his gold medal, Spitz placed a pair of adidas sneakers behind him. After the playing of the Star Spangled Banner, Spitz picked up the shoes and acknowledged the crowd by raising his arms. The Soviet Union claimed Spitz was advertising for adidas and, consequently, violating the Olympics’ rule of amateurism. The International Olympic Committee looked into the incident, but cleared Spitz of any wrongdoing. It was obvious that if Spitz couldn’t be beaten in the pool, opponents would try to find a loophole to eliminate their biggest obstacle.

“I’m already a Jesse Owens,” Spitz kidded. “Now they’re trying to make a Jim Thorpe out of me.”

Spitz was referring to the fact that he already had the success of Owens, who won four gold medals in track and field at the 1936 Olympics, but was being attacked like Thorpe. A gold medalist in the pentathlon and decathlon at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Thorpe had his medals revoked by the IOC (years later, after Thorpe’s death, the medals were restored) because he was paid briefly as a professional baseball player.

Spitz’s fourth and fifth medals (and world records) were earned on August 31 when he prevailed in the 100 butterfly and as a member of the 800 freestyle relay. Spitz had no problem in either event, winning by more than a second over Canadian Bruce Robertson in the 100 butterfly and by six seconds with his teammates over West Germany in the 800 freestyle relay.

Photo Courtesy: ISHOF Archives

As Spitz rolled through his program, the pressure he felt at the beginning of the Games largely eased. Still, he had some concern over his final individual event, the 100 freestyle. Spitz was beginning to feel weary from his demanding schedule and he knew Heidenreich would bring a challenge, along with defending champion Michael Wenden of Australia. At one point, the possibility of withdrawing crossed his mind.

“Each day that I swam and I won a gold medal, it was like one brick shy of a load getting off of the cart,” Spitz said. “And so, I felt that I was actually having a better go of it. But I was exhausted by the time it came to my last individual event, the 100-meter freestyle. And I have to say that the last stroke that I took at the Olympic Games, I don’t think I could have taken another stroke. I was 100 percent up until the last stroke, and I literally had one drop of gas in my tank at the end of that. So thank goodness it ended.”

Spitz surged at the start of the 100 freestyle, a tactic which surprised Heidenreich, who expected Spitz to save some energy for the latter half of the race. While Heidenreich closed the gap on his teammate over the last lap, he fell short of catching Spitz, who set a world record of 51.22, ahead of the 51.65 by Heidenreich. Wenden proved to be a non-factor, finishing fifth.

For Spitz, his final day in the pool was primarily a formality. He picked up his seventh gold medal with ease, handling the butterfly leg of the 400 medley relay. The team of Mike Stamm, Tom Bruce, Spitz and Heidenreich was timed in 3:48.16, four seconds clear of East Germany. For Spitz, the end featured a combination of jubilation and relief.

After the relay, Spitz’s teammates carried him around the deck for a well-deserved victory lap. It’s a moment which Spitz has never forgotten.

“That picture with my teammates holding me high above them I enjoy more than the one that was taken with the seven gold medals around my neck,” he said. “Having a tribute from your teammates is a feeling that can never be duplicated.”

Spitz’s achievement figured to be the talk of the remainder of the Olympics, but in the early hours of September 5, only several hours after Spitz completed his perfect week, the terrorist group Black September took 11 members of the Israeli Olympic delegation hostage. A faction of the Palestine Liberation Organization, Black September broke into the building holding the Israeli athletes and coaches and used deadly force in the hostage-taking.

Mark Spitz as an Arena ambassador the first time round – Photo Courtesy: by Graham Morris/Evening Standard via Getty Images, courtesy of arena

When Spitz woke the next morning and made his way to a final press conference, he was unaware of what was unfolding. Soon, he was clued in on the details and because of his Jewish religion, officials informed Spitz he would be ushered out of Munich. By 5 o’clock at night, Spitz was in a car, an Army blanket draped over his head, and taken to the airport for a flight to London.

Ultimately, negotiations between German police and government officials failed and the 11 Israeli hostages were killed, along with five of the eight Palestinian terrorists. The Games went from being a joyous occasion to a somber event.

“It was terrible. I mean, you know, the Olympic Games today is modeled based on the security not only for the athletes, but for the press, the media, the spectators, and the citizens of a host city,” Spitz said. “And the International Olympic Committee has done a great job over the years to protect everybody. But it’s totally different. Here I became a real gigantic event as a sports celebrity winning seven gold medals. Then it became a news event. And then all of a sudden it became a tragedy. And then it became elevated at a much higher level, and we’re talking about it right now, 40 years later.”

Although Spitz retired after the Munich Games, his name has remained a constant in the sport. Anytime a multi-event talent comes along, comparisons to Spitz are made, even if they are a stretch. Really, it wasn’t until the mid-1980s when a legitimate comparison surfaced, thanks to the talent of Matt Biondi.

Like Spitz, Biondi raced the freestyle/butterfly combination and embraced a program which featured seven events. In the leadup to the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, Biondi couldn’t escape Spitz’s shadow. Never did an interview end without Biondi being asked about matching Spitz’s seven gold medals, despite Biondi never once suggesting it was a goal.

“I don’t feel it’s a fair comparison,” said Biondi’s coach, Nort Thornton, of the Spitz comparisons. “But people are going to do it. You can’t stop them. It’s unfortunate people get compared, but that’s human nature. The rules have changed, and people can’t swim as many events as they were able to in 1972. There are certain comparisons like the speed they both travel through the water, but Matt is definitely not Mark. He is his own swimmer. Someday people will be comparing another young swimmer to Matt. That’s the way it works.”

Biondi enjoyed a sterling showing at the Seoul Games, leaving with five gold medals, a silver and a bronze. As impressive as he was, Biondi was actually painted as a failure by some media outlets. The same scenario befell Michael Phelps in 2004, when he became the latest American star to hear the Spitz comparisons.

An Olympian as a 15-year-old in 2000, Phelps started to show his versatility a couple of years later, namely at the 2002 United States National Championships. There, Phelps won the 100 butterfly, 200 butterfly, 200 individual medley and 400 individual medley, victories which were complemented by a third-place finish in the 200 freestyle. It was a week which got the wheels turning in the head of Bob Bowman, Phelps’ coach.

“I thought that Michael could do a lot of stuff, but it was then that I thought about Spitz’s record and told myself, ‘Wow, he can really do this,’” Bowman said of the 2002 National Championships. “That was in the back of my mind, but I still didn’t want to think about seven medals. The way to think about seven medals isn’t to talk about it, it’s to train. When we left that meet, we knew at the least, that Michael was going to be our Ian Thorpe.”

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

When Phelps came back from the next year’s World Championships with six medals, the Spitz talk was in full effect. And when it was announced that Phelps would contest eight events at the 2004 Olympics in Athens, Phelps had no chance of turning back the Spitz queries. Trained by his management group at Octagon Sports, Phelps knew exactly how to handle the Spitz question.

“Records are always made to be broken no matter what they are. Anybody can do anything they set their mind to,” Phelps said. “I’ve said it all along. I want to be the first Michael Phelps, not the second Mark Spitz. Never once will I ever downplay his accomplishment and what he did. It’s still an amazing feat and will always be an amazing accomplishment in the swimming world and the Olympics.

“To have something like that to shoot for, it made those days when you were tired and didn’t want to be (at practice) and just wanted to go home and sleep, it made those days easier to be able to look at him and say, ‘I want to do this.’ It’s something that I’ve wanted to do, and I’m thankful for having him do what he did.”

Phelps’ first attempt at Spitz’s standard came up short in Athens, but the effort was nothing but spectacular. Competing against deeper competition than Spitz and forced to handle a more arduous schedule, Phelps won six gold medals and two bronze medals.

Four years later, he was even better.

At the 2008 Games in Beijing, Phelps was a perfect 8-for-8 and moved ahead of Spitz as the greatest athlete in a single Olympiad. Phelps needed a couple of miracles along the way, notably a come-from-behind anchor leg by Jason Lezak in the 400 freestyle relay and a fingernail triumph over Serbian Milorad Cavic in the 100 butterfly. But Phelps got the job done and became the new measuring stick for Olympic greatness.

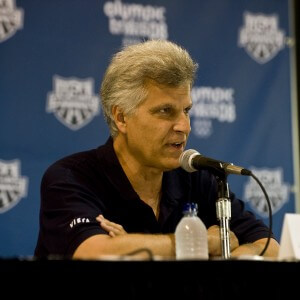

During Phelps’ emergence as a global superstar, Spitz was difficult to read. At times, he seemed gracious and respectful toward Phelps’ talent. At other times, he wondered if Phelps could pull off his pursuit.

“I set a record that lasted 36 years until Michael Phelps broke it,” Spitz said. “It’s amazing that I was an inspiration to someone not even born yet to achieve and excel in my sport. That’s the greatest accolade I could leave for my sport and the Olympic movement. What is a higher regard?”

Yes, almost five decades have passed since Mark Spitz wowed the sporting world with what was the finest performance in Olympic history. While his seven-gold effort has since been surpassed, Spitz’s legacy is going nowhere. He will always remain a legend, what he produced in 1972 a special showing.

Also when the Israelis team was killed by terrorists

Mark was my inspiration to get into competitive swimming at age 11. Met him once during my career.

The power of the mustache’ was on full display.

Peggy Wisette Swantek

Legend. He’s the reason my son is swimming with Santa Clara Swim Club. ? ??????

Oliver Whittleston

Q: Do you know how they fill up Olympic swimming pools? A: Mark Spitz. (This has been a bad joke for 48 years….)

Yep ?, I was in Army stationed in Germany ?? in 1972…exciting times.

No goggles, no cap. Things have changed since 1972

Winston Niles Rumford swimmers should be able to swim without goggles! They do help though!

Winston Niles Rumford but he swam with that moustache

Also, no speed suit or tattoos. It really was a different world.

Lol!! My son’s butterfly stroke looked similar!

John Drake- his life size poster hung over our pool.

I remember it like it was yesterday.

I like the asymmetrical arm action in an Olympic medal winner. It shows you don’t need a perfect stroke to achieve.

Paul Robbins best to teach it proper. It they get it wrong but get gold, great!

Inspired me to take up the sport! See fly swimmers were not always massive!

I always wonder what Mark Spitz could have done had he been born in 1985 instead of 1950. With swimming technology and techniques do you think he could hang with Michael Phelps?

The question should be, could Michael Phelps hang with Mark Spitz?

There is a video of him swimming butterfly (arms) with a glass of water on his head, was posted recently, and he is 70 now ! What a spirit!!!Happy aniversary, Mark!!! You are a legend!!!:)

I think Mark Spitz did a good job of transitioning from sports hero to family man and business professional. He put his swimming glory into proper perspective. Michael Phelps is probably the greatest swimmer of all time, but I am surprised at his emotional struggles after his success at the Olympic games. There is more to life than just swimming glory. You have to have a life after your athletic career ends, and all the personal glory fades into the history books.