Happy 80th Birthday Lance Larson – Sub-Minute Butterfly Pioneer Who Triggered The Timepad

Lance Larson turns 80 today in the same week in which, sixty years ago, he became the first swimmer to race inside the minute over 100m butterfly.

The American, better known for the first place at the Olympic Games that resulted in the faster swimmer being handed the silver medal over 100m freestyle in the days when the naked eye counted for more than the clock, clocked 59.0sec over 100m butterfly on June 26, 1960.

With that swim, Larson had done for butterfly what fellow American Johnny Weissmuller had done on freestyle in July 1922: he shattered the existing speed standard with an effort that swept pioneering pace well inside the minute.

On June 29, 1958, Japan’s Takashi Ishimoto had axed 0.9sec off his own global standard to leave the ‘fly mark at 1:00.1. It would only be a matter of time before the barrier would fall. Come the hour, Larson left no doubt, with a following wind, his 59.0sec now 60 years old as the pioneer turns 80 today.

Lance Larson was born on July 3, 1940 at Monterey Park, California. He grew to be 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m), weighed in at 174 lb (79 kg), excelled on butterfly, freestyle and medley and raced for the Los Angeles Athletic Club and, in college, the University of Southern California

Larson attended El Monte High School. He set CIFSS (California Interscholastic Federation-Southern Section) records of 55.5 and 54.6 over 100 yards butterfly in 1957 and 1958, the latter the same year he took the 100-yard freestyle standard down to 50.9. Larson later became the first high school swimmer to break 50sec over 100-yard freestyle but his pioneering sub-minute 100m butterfly is more widely known.

Racing for USC Trojans at NCAAs, he won free, ‘fly and medley titles and claimed Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) national crowns in all three disciplines, too. Rome 1960 was a crowning moment that might have been all the more spectacular had it not been the last Games before timing would count for more than the naked eye and one of the last before the introduction of a race program more akin to that we know today.

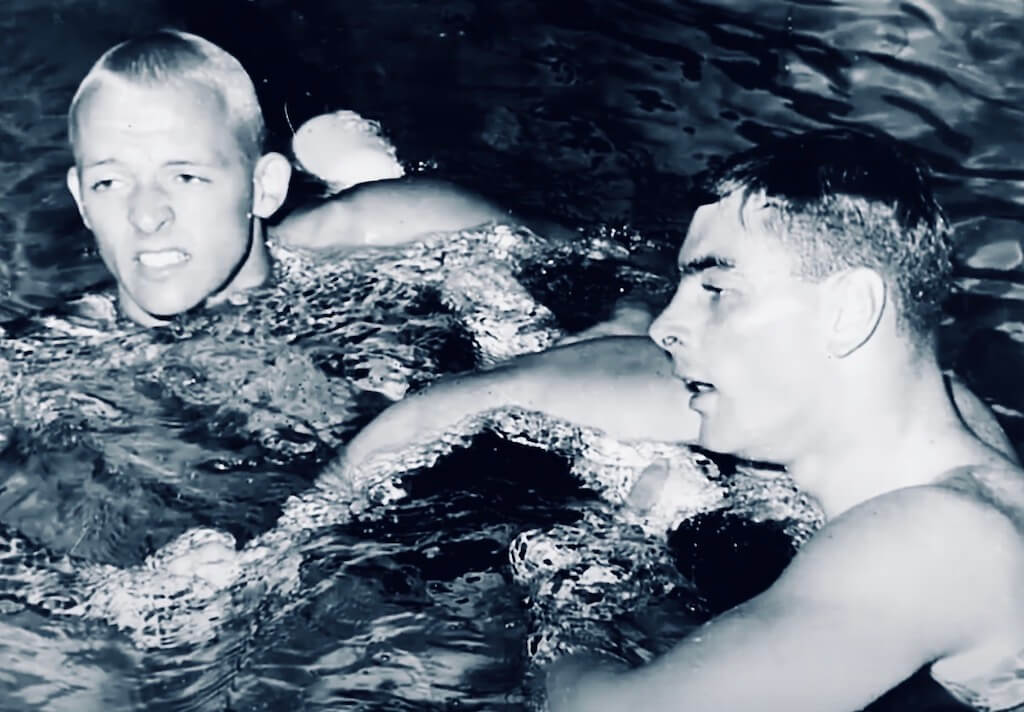

Jeff Farrell, Lance Larson, Paul Hait and Frank McKinney – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

At the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, he claimed gold in the 4x100m medley and a controversial silver as the fastest man home in the 100m freestyle.

Larson later married Betty Lee Puttler (1940–2007) of Newport Beach, California and the couple had four sons, Lance Jr., Greg, Gary & Randy. Lance Lanrson senior remarried in the late 1990s, and has two adopted daughters.

Retired since 2014, he lives in Southern California’s mountain community after a career operating a dentistry practice in Orange, California from 1979 onwards.

He was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame as an “Honor Swimmer” in 1980.

Lance Larson The Unlucky Swimmer Granted Silver As The Fastest Man Home

Lance Larson, right, and John Devitt, middle, after a controversial judging decision handed the Australian gold in a 100m freestyle final at Rome 1960 in which Manuel Dos Santos, of Brazil, claimed bronze – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF film still

Lance Larson may well be regarded as one of the unluckiest swimming champions in history. Consider this unfortunate circumstances:

- his 55.1sec timing over 100m freestyle clocked in the Rome 1960 Olympic final was declared an Olympic record a year after he swam the time only to find himself handed the silver medal behind Australia’s John Devitt

- he was the dominant 100m butterfly swimmer of the summer of 1960, taking the global mark down to 58.7 on July 24 a month before the last Olympic Games not to feature the 100m butterfly (a ‘pure’ sprinter, he was fourth at U.S. trials over 200m butterfly)

- he was part of a USA 4x100m freestyle quartet in summer 1960 that would surely have shattered the world record for Olympic gold had the 4x100m freestyle been added to the program in 1960 not 1964 (Larson and Farrell held the world record with Ed Follett and Joe Alkire at the time of the Rome Olympic Games)

He might have come away from Rome with four golds if the sands of time had shifted in his favour but they did not and the gold he claimed in the 4x100m medley with Frank McKinney, Paul Hait and Jeff Farrell represented his only visit to the loftiest place on the podium. His bonus with team-mates was a world record of 4:05.4, inside the 4:08.2 clocked by his prelim teammates Bob Bennett, Hait, David Gillanders and Steve Clark, who would shatter the 100m free World record a year later on 54.4 in Los Angeles.

Devitt had set the global standard at 54.6 on January 28, 1957 – and that’s where the mark stayed all the way to the Olympic final in Rome. In December 1956, after deciding that only long-course swims would count for World records, FINA declared the 55.4 in which Australian Jon Henricks had claimed 1956 Olympic gold in Melbourne the first global 100m free standard of the new era.

When Devitt became the first below 55sec long-course on January 28, 1957 in Brisbane – breaking the World record of 54.8 by Dick Cleveland, of the USA, in a short-course pool – FINA had a rethink, scored Henricks out of the list and made Devitt’s time the first pioneering effort of the long-course era.

By Rome 1960, Devitt remained a golden shot – but with his 55.0 American record from trials, Larson was a clear threat.

From The Archive:

The 100m Free Final That Accelerated The Age Of Electronic Timing

John Devitt (AUS) was the last swimmer to win an Olympic gold medal in the pool where the human eye was judged preferable to manual timing and the first electronic device that registered manual times to a hundredth of a second.

John Devitt (AUS) was the last swimmer to win an Olympic gold medal in the pool where the human eye was judged preferable to manual timing and the first electronic device that registered manual times to a hundredth of a second.

He entered the Rome 100m showdown as world record holder and 1956 silver medal winner. Third at the turn, Devitt took the lead at 70m and looked like the sure winner. But in the closing metres Lance Larson (USA) surged: there was nothing in it at the touch.

Three judges went with the Australian, three with the American, while the clock favoured the American, on 55.0, 55.1 and 55.1 to the Australian’s 55.2, 55.2, 55.2. Some references describe the use of an electronic-timing device but the machine that was used was electronic only in the sense of relaying the data to a printer and recording times to a hundredth of a second. The times registered on the device were in fact manual, the result of an official pressing a button on sight of a swimmer touching the wall, in the same way that a timekeeper stops a hand-held watch.

That electronic readout also had Larson ahead, 55.10 to 55.16. Despite all that evidence, Sweden’s Henry Runströmer, the chief judge who, under prevailing FINA rules did not have final say in the matter, instructed recorders to change Larson’s time to 55.2 and to grant gold to Devitt. The decision stood. It was over a year before the facts of the case came to light when an investigative journalist uncovered the records of the timing system. Years of protests all the way to Tokyo 1964 failed to overturn the decision.

The controversy motivated Omega to work on electronic timing systems, with time-pads, that would cause further controversy by 1972, when timing was registered to a thousandth and Sweden’s Gunnar Larsson took gold in the 400m medley over American Tim McKee 4:31.981 to 4:31.983. McKee was handed silver, while both men were granted the Olympic record to the hundredth of a second, which has been the standard in swimming ever since the Munich Olympics controversy.

The 100m free final in Rome sparked several documentaries and many a written word down the years. Here are four fine examples. the first with a recollection from Lance Larson himself.

A clearer view of the Rome 1960 final. Devitt ended his career with two golds (100m, 1960; 4x200m 1956) a silver (100m, 1956) and a bronze (4x200m, 1960), and four individual and 10 relay world records to his credit. Oddly, he did not race the freestyle leg of the Australian medley quartet that claimed silver in Rome behind a US quarter, including Larson, that broke the world record.

The Birth of Butterfly In The Era Of Lance Larson

The Rome controversy is what Lance Larson became known for, overshadowing the pioneering speed he achieved on butterfly, a stroke that was officially four years old when Lance Larson cracked the minute 60 years ago, although dolphin and the butterfly arm stroke was much older than that.

Back in 1911, a man called George Corsan, a Canadian chief instructor and pool designer for the YMCA and author of some of the first definitive books on swimming instruction, was to be found teaching a fishtail action in swimming that would ultimately lead to the birth of modern butterfly in 1952.

Between the early use of dolphin action among competitive swimmers and FINA’s vote at 1952 Congress to create butterfly as a stroke apart from breaststroke and sew the seed of medley, breaststroke was a stroke in development: FINA law had enough loopholes in it to make a Swiss cheese blush.

On tour in the US in 1927, Eric Rademacher, of Germany, then world record holder on breaststroke, displayed a technique that involved pulling back to the hips underwater and wheeling the arms overhead for the last stroke into turns. Around the same time, Australian Sydney Cavill, one of several famous swimming members of the Cavill family, was credited as the inventor of the butterfly arm stroke. Communication was not then what it is now and there is no telling who got to a butterfly arm stroke first.

Suffice it to say that the underwater technique was used by all medallists at the 1928 Games, but none, barring Canadian Walter Spence, in sixth, dared use the overhead arm action for fear of disqualification. Their fears were unfounded.

David Armbruster, coach at University of Iowa, took it all further when he instructed his charges to do a fishtail action. One of Armbruster ‘s charges, Jack Sieg, developed a type of sideways kick, beating his legs together like a fish tail. It was 1933, and Armbruster called it the “dolphin fishtail kick.”. A year later, the overhead arm and dolphin kick were placed together for the first time.

References to a dolphin action related by Armbruster, coaching mentor to the legendary James “Doc” Counsilman, in homage to the ubiquitous Corsan appeared in the late 1920s.

In December 1933, Henry Myers became the first person to race continuous butterfly arms when he won a 150-yard medley race. Officials studied the rulebook but could find no reason to declare Myers in default. For the next 19 years, the stroke would be known as “butterfly-breaststroke”. At the 1936 Games, Maria Lenk (BRA) used butterfly arms in the 200m breaststroke heats and semis.

At the London 1948 Olympic Games, the 200m breaststroke final won by Joseph Verdeur (USA), saw seven men use an over-arm stroke.

The one man in the final won by Verdeur who used traditional breaststroke, Bjorn Bonte, of The Netherlands, paid the price of a sport that had yet to batten down the hatches on what the stroke would become: he was last.

During the same years that Rademacher, Myers, and Cavill were developing the overall stroke, a young physicist named Volney Wilson was to be found at the Shedd Aquarium, in Chicago, watching aquatic mammals and fish in the aquarium. Later a collaborator on the Manhattan Project, Wilson, known to his friends as Bill, practiced what he saw the creatures preaching. An avid swimmer, he noticed that fish moved their tails from side to side but the mammals in the water, the whales and dolphins, moved their tails up and down.

Wilson swam at the Chicago Athletic Club, and began to try the dolphin kick himself. He never made it to an Olympic Games and as such, his contribution to the development of butterfly (and at first faster breaststroke before the birth of butterfly and the placing of breaststroke back in a specific box, is often overlooked.

Wilson “Bill” Volney, passed away in 2006, aged 96, a swimmer late into that long life.

Butterfly Spreads Its Wings

Eighteen years would pass after Armbruster and Sieg first using ‘fly arms and a fishtail kick before FINA would recognise the need to distinguish between breaststroke and butterfly.

At its 1952 Congress in Helsinki on July 23, two distinct strokes, “Orthodox Breaststroke” and “Butterfly Breaststroke,” were born. While the 1952 breaststroke/butterfly ended two decades of uncertainty over breaststroke, not all loopholes had been closed.

At the Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games, FINA Congress agreed that “no competitor is allowed to use or wear any device to help his speed or buoyancy during a race”, while “swimming under the water is prohibited except for one initial arm stroke and one leg kick after start and turn” on breaststroke.

That new rule would only take hold on May 1, 1957, too late to stop Masaru Furukawa, of Japan, becoming the most invisible champion in Melbourne, having swum underwater for some 150m of the 200m breaststroke final, surfacing only for breathing, for turns and the final approach to an Olympic record of 2mins 34.7sec ahead of teammate Masahiro Yoshimura and the first Soviet swimmer to win an Olympic medal, Kharis Yunichev.

However, it was the interpretation of existing rules that caused even greater controversy: among six swimmers disqualified in the 200m was Herbert Klein (GER), 1952 bronze medallist and former world record holder. His misdemeanour: a scissor kick and dipping his right shoulder. The judging decision caused schism in FINA: Max Ritter, the Vice-President born in Germany and representing the USA, boycotted the post-Games Congress at which he would have been elevated to President. FINA members felt that Furukawa’s victory was achieved “against the spirit of the sport” but stuck with the judge’s decision on Klein.

The Pioneers Of Butterfly Pace

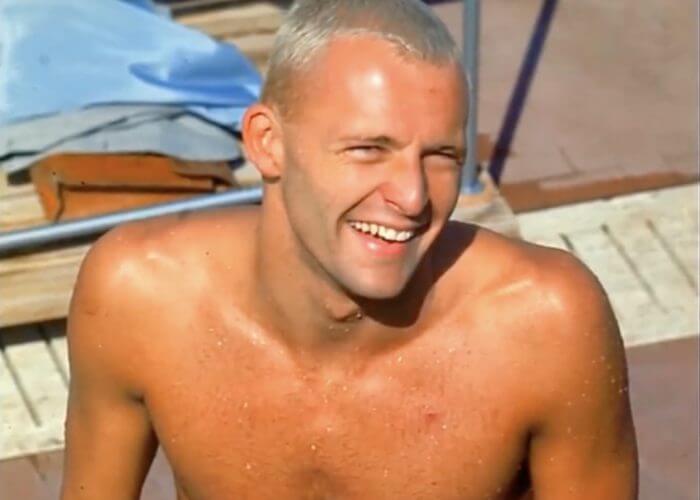

Lance Larson – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF film still

The European Championships in Turin, Italy, in 1954, marked the first big occasion on which the new stroke was seen: Gyorgy Tumpek (HUN) claimed the 200 m butterfly crown in 2:32.2.

The first official world record for a woman on butterfly was set by Jutta Langenau (GDR) in 1:16.6 over 100 m (August 31 1954), that time inside the 1:16.9 in which Eva Skzekely (HUN), 1952 Olympic 200 m breaststroke champion, had set the world breaststroke record while swimming butterfly (May 9, 1951), before the split of strokes. Over 200m, Tineke Lagerberg (NED) opened the record book at 2:42.3 (December 12, 1956). Among men, Tumpek’s

1:04.3 (May 31, 1953) was inside the 1:05.8 clocked by Herbert Klein (GER) with a butterfly action on breaststroke (February 17. 1952). Klein’s 200m breaststroke standard (again, using butterfly) of 2:27.3 (June 9, 1951), was surpassed by Jiro Nagasawa (JPN), over 200 m butterfly, in 2:21.6 (September 17, 1954).

By 1956, the Olympic Games knew butterfly and breaststroke. The inaugural Olympic titles went to Americans Shelley Mann and William Yorzyk. Coached by Charles “Red” E. Silvia, Yorzyk was the first to use two kicks to one ami cycle on butterfly and the first to use the every other stroke breathing cycle. He and Silvia issued the first film dedicated to teaching butterfly.

Among pioneers of the new strokes were Dutch trio Atie Voorbij, Tineke Lagerberg (both butterfly), and Ada den Haan (breaststroke), who in the year they broke world records were deprived by a 1956 Dutch boycott of challenging for Olympic titles.

Medley made it to the Olympic Games in 1960.

Down the years, breaststroke rules were ironed out, clarity introduced on issues of touching walls with two hands, in line and not; on whether the head can go below the surface or not, and so on. Today, one dolphin kick is allowed off the wall on breaststroke – but dolphin kicks can be seen in the course of all four strokes and the medley at Olympic level, the birth of the “Fifth Stroke” a part of that long history (for another day).

Meantime, Corson, he of the 1911 story from Armbruster, was not done back there: much later in life, with his arms legs tied together, the father of competitive dolphin fishtailed down the length of the 55-yard Casino Pool at the Fort Lauderdale Swim Forum to demonstrate where it all stemmed from. He was 90 years old.

At 80, the pioneer of 1960 has a decade to catch up on Corsan. Many Happy Returns Of The Day, Lance Larson!

And Happy Birthday to the legend, Mike Burton …as well

?

Bill Strömberg ? 73 (just not round enough ? … many happy returns of the day, Mike Burton ?

Your cousin Jim…

Bob Perkins of course. Looks just like me! Blonde hair and all!

Your hairs are blond…

Happy Birthday

Mary Skill ?

Larson and Devitt was as close as they come with the decision going to Devitt.

Tim McKee and Gunnar Larsson recorded the same time in the 400 IM in Munich.

Larsson got the gold.

Rules got changed then as well

Yes, all mentioned in the article, Neil.

We have come a long way

Thanks Craig for this great story on my Dad, well done!

— Lance Jr.

Thanks for the kind comment, Lance Jr. Your dad is a special part of the deep thread of rich swimming history. He doesn’t know me but please send him my kindest regards All the best, C

All the best, C

Thank you Craig! Excellent review, I grew up with the story but learned new facets of the controversy from your research and writing. Sharing with tons of friends! Best, Greg Larson

Greg. Thanks for your kind note. Kind regards, Craig