Haley Anderson & Ashley Twichell Stay Safe/Honour Fran By Pulling Out Of Qatar Beach Games

Memory Of Fran Crippen Demands Safety-First Response From USA Swimming

Haley Anderson and Ashley Twichell, the top two American women open water swimmers, will not race at the ANOC World Beach Games in Qatar this weekend as planned because water temperatures are expected to exceed upper limits imposed after the death of their fellow American Fran Crippen in 2010.

USA Swimming confirmed the decision and explained:

“Based on water temperature data and USA Swimming’s recommendations concerning athlete health and safety, National Team athletes Haley Anderson and Ashley Twichell have made the decision not to attend the ANOC World Beach Games Qatar 2019.”

Anderson, the 2012 Olympic marathon silver medalist and twice world champion, and Twichell, also twice a world champion, claimed bronze together for the USA in the open water team event at the World Championships in Gwangju last July.

Their withdrawal from the 10km race this Sunday will be welcomed by all who place athlete safety first. It remains to be seen if open water racing takes place at all at the Beach Games as a result.

Marathon open water temperatures, already 3C higher than the upper limit for a swimmer racing just one lap of a 50m Olympic pool, are just one side of the coin: the air temperature plays a significant part, too, when determining if conditions are safe to race.

At the World Athletics Championships in Qatar last week, the IAAF nominated Braima Suncar Dabo as a candidate for the Track and Field federation’s Fair Play Award after he helped a fellow runner suffering from heat stroke. On the final lap of his 5000m heat, the runner from Guinea Bissau helped carry fellow competitor Jonathan Busby to the finish line when he was on the brink of collapsing.

While concern has been expressed for soccer players at the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, this past week delivered a report suggesting that hundreds of migrant laborers are being “worked to death in searing temperatures there, with hundreds estimated to be dying from heat stress every year.”

A Guardian investigation revealed that among the hundreds of thousands of migrant workers in Qatar to build sports stadiums in temperatures of up to 45C for up to 10 hours a day, mortality rates are alarming.

The dangers of excessive air temperatures are just as just as keen for swimmers, especially in waters of more than 30C.

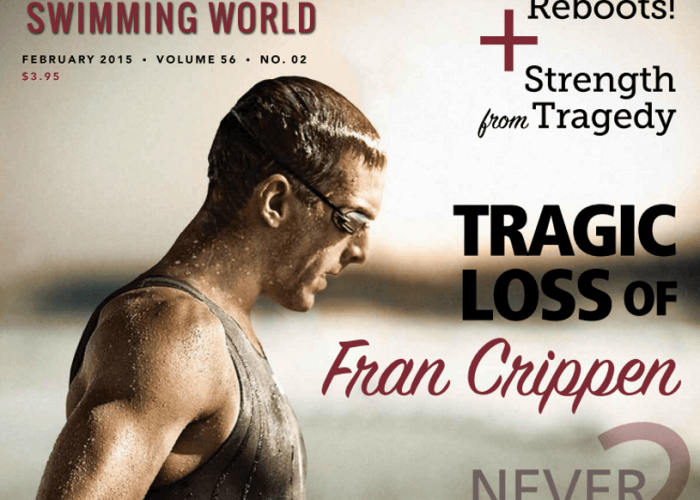

Fran Crippen – Never Again Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Magazine

The place and time of the Beach Games, run by the Association of National Olympic Committees, is extremely sensitive. Two inquiries found serious flaws in the organisation of the 2010 FINA World Cup race in which Fran Crippen died off the coast of the United Arab Emirates in 2010. This month marks the ninth anniversary of Fran Crippen’s death, the first in FINA competition.

A rule setting the upper water temperature limit for racing at 31C came into force because of Fran Crippen’s death. It has not, however, always been observed, even at events where senior FINA officials have been in positions of authority. American and Japanese teams have both withdrawn from international competitions as a result of unacceptably hot waters but races have gone ahead with official approval despite the clear dangers and the new rule book.

Two inquiry reports, one commissioned by FINA, the other by USA Swimming, concluded that there were glaring safety deficiencies on the fateful day Fran Crippen died and noted that FINA had fallen short on oversight at its showcase event.

FINA did not sanction the UAE, while Ayman Saad, the Egyptian executive director of the UAE swimming federation, was subsequently added to FINA’s technical Open water Swimming Committee.

On the day Fran Crippen died, Saad told international news agencies and other media: “We are sorry that the guy died, but what can you do? This guy was tired and he pushed himself a lot.”

Autopsy reports confirmed that water temperatures over 31C and by some estimates up to 34C, combined with air temperatures of over 40C had contributed to heat exhaustion in the swimmer. There was no indication of any problem with his heart or other vital organs. The likelihood, said experts, was that his body could, effectively, no longer sweat, given the conditions, he passed out and drowned.

At the end of the race, several swimmers needed medical attention and some were taken to hospital by ambulance.

USA Swimming’s attention to open water conditions is keen these days. Back in 2010, the federation did not have any professional staff accompanying its swimmers to the UAE, while in the two weeks leading to the FINA World Cup race, Fran Crippen had written to Chuck Wielgus, then the CEO of USA Swimming, to urge him to appoint team staff to travel with swimmers on safety and other grounds.

Another factor that contributed to concern was the rule that insisted swimmers not only attend the last cup race of the season but also finish it if they were not to forfeit their season prize money.

Of the field, all but one swimmer made it to the finish, 81 swimmers in all. American Christine Jennings was among those who emerged from the race in a poor physical condition and received medical assistance before being taken to hospital.

No one had noticed that Fran Crippen was missing until his teammates, led by Alex Meyer, raised a red flag. Only then did a frantic search begin, Fran’s body found some two hours later.

Under pressure from athletes and federations, FINA followed recommendations for an upper water temperature limit of 31C to be set. Despite that, several races have now taken place in conditions that break those new rules that stand as a pledge and promise to the legacy of Fran Crippen, to the Crippen family and to every open water swimmer in the world.

American swimmers have withdrawn from open water competition before on grounds of safety, while in 2015, they boycotted the return of the FINA World Cup to the UAE.

At the time FINA Executive Director Cornel Marculescu told ESPN:

“You cannot banish for life a federation where this happens. This is very sensitive, a big tragedy, but there are deaths and accidents in other sports and the races are still there. For sure, there were mistakes on the course [in 2010]. They will take all the necessary steps so no one can disappear like that again.”

Fran Crippen – Photo Courtesy: ABCNews.com

In 2017, Richard Shoulberg, Fran Crippen’s coach, complained that the 10km events at the Asian Open Water Championships, off the Malaysian coast had been allowed to proceed despite water temperatures of 31.9 degrees Celsius.

FINA official Ronnie Wong, who served as chairman of the international federation’s Technical Open Water Swimming Committee when it established rule OWS 5.5 (specifying temperature limits), gave a thumbs up to the race off Malaysia.

Team Japan complained but Wong and other FINA officials dismissed the protest and let the race go on. Japan withdrew its enquire team on safety grounds.

Wong is a member of the Asian Swimming Federation’s Bureau led by Sheikh Ahmad al-Fahad al-Sabah, who is described on the ANOC official website as “self-suspended” president of the organisation hosting the Beach Games.

Sheikh Ahmad, who caused a stir when he introduced himself to Konstantin Grigorishin, founder of the International Swimming League, as the man who “runs world swimming” even though he has no official function at FINA, is currently awaiting a court hearing in Switzerland over allegations of fraud.

TOKYO 2020 Waters Under Surveillance

Meanwhile the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Marathon may be swum as early as 4 or 5 a.m. next year if conditions demand. A monitoring organisation is to be set up to monitor water conditions and temperatures ahead of the Games next July after swimmers at an Olympic test event complained of hot waters.

“That was the warmest race I’ve ever done,” 2012 Olympic champion Oussama Mellouli told the Japanese Times after completing the 5-km men’s competition. “It felt good for the first 2 km then I got super overheated.”

The event started at 7 a.m. with the air temperature already over 30C in the Japanese capital. “The water temperature was high so I’m a bit concerned about that,” said Yumi Kida, who said she guzzled iced water before the race in an effort to reduce her body heat.

Marculescu said: “Based on this information, we will decide the time the event will start. Could be 5 a.m., could be 5:30 a.m., can be 6 a.m., can be 6:30 a.m. — depends on the water temperature.

“Working with a specialized company like we are going to do here in Tokyo, we will have the right information to take the right decision.”

The Background:

FRAN CRIPPEN – THE U.S. INQUIRY REPORT IN FULL:

Fran Crippen – Photo Courtesy: Fran Crippen Elevation Foundation

1 Open Water Review Commission Recommendations – April 12, 2011

The Commission has been charged by USA Swimming to “review the circumstances surrounding the death of Fran Crippen in order to make recommendations for the improvement of safety protocols, procedures, and precautions for future domestic and international open water competitions.”

Because FINA has declined to provide information as to the circumstances on the day of the race until after it has issued its report, the Commission has not been able to complete a review of the circumstances surrounding Fran Crippen’s death. Requests for information have been made of FINA by the investigators engaged by USA Swimming, by USA Swimming staff and by the Commission. To date, no information has been provided by FINA.

The Commission has decided that the importance of improvements in safety protocols, procedures and precautions in a discipline such as open water swimming, with its particular risks, is such that proposals for the improvements must be considered whatever the circumstances of Fran Crippen’s death may have been.

It goes almost without saying that there must be immediate recognition when a swimmer is struggling or loses consciousness; there must be immediate rescue when loss of consciousness occurs; and there must be immediate resuscitation to address medical emergencies.

While it seems fairly clear that Fran Crippen lost consciousness as a result of heat exhaustion, there are many medical conditions which might lead to the same result. The difference between losing consciousness in a land-based event and an open water event is quite unique. The open water swimmer will sink and start to aspirate water instead of air and the progressive lack of oxygen will not cause the swimmer to “wake up.” Once this occurs, rescue must take place very quickly in order to avoid serious medical consequences, including death.

The recommendations which follow are circulated for consideration by USA Swimming and the open water community generally. They were adopted unanimously by the Open Water Review Commission:

Richard Pound, Chair; Sid Cassidy; Harold Cliff ; Dr. Scott Rodeo; Erica Rose

2 All open water races organized by a responsible federation (FINA for FINA events and USA Swimming for USA Swimming sanctioned events) shall satisfy the following:

Part 1: Approval and Implementation of a Safety Plan

No open water competition will be sanctioned unless the safety plan for the competition has been approved by a committee of safety experts. That safety plan must comply with the requirements set forth in Part 2 (below).

A safety officer approved by the responsible federation and independent of the race organizing committee must be present at each race in order to assure that the approved safety plan is implemented and to assure that adequate safety precautions are in place to deal with race-day conditions. The safety officer must have authority to withdraw the sanction on race day if adequate safety precautions are not in place. The race director and race referee shall each have a similar authority. If the sanction of a race is revoked, but the race organizer nevertheless goes forward with the race, notification of revocation due to safety considerations must be given to all race participants prior to the beginning of the race.

Any one of the safety officer, race referee or race director shall have the authority to stop a race at any point during the course of the race should conditions change and safety become a concern.

Part 2: Safety Plan Requirements

A safety plan shall include the following minimum requirements:

A. Monitoring Swimmers During Race

One of the most critical topics related to swimmer safety during open water races is the concept of “who is watching the swimmers?”

Requirements:

- 1. For all open water races, certified, local lifeguards experienced in open bodies of water must be a part of the safety plan of the race.

- 2. All athletes must be observed at all times during the race by a member of the safety team.

- 3. Each race must have an appropriate number of first responders dedicated to the race, who are able to react to a need for assistance within 10 seconds, and are able to reach the swimmer within an additional 20 seconds.

- 4. Each race must take into consideration its course and set-up and determine if safety personnel should be assigned by zone, by following athletes through the course, or by a combination of both.

- 5. In an unescorted race, there must sufficient safety craft on the course to very quickly remove an athlete from the water. A ratio of one safety craft for each 20 swimmers is required. This ratio can only be modified with the approval of the sanctioning body (for example, in some races, a swimmer could be rescued directly by shore personnel without the use of a safety craft).

B. Safety Communications Plan

A safety communications plan is required for all races. The responsible federation should develop a safety communications plan template which would be made available to all race organizers.

Minimum Requirements:

- 1. A safety communications plan must enable efficient water-to-water, water-to-land and land-to-water communications. Unless otherwise approved by the sanctioning body, two-way radios, with one channel reserved for emergency communications, will be required (for example, it may be acceptable in some circumstances for safety personnel using kayaks to communicate with a system of whistles and hand signals).

- 2. Personnel on all boats, safety craft and feeding platforms must have the ability to communicate with the safety officer.

- 3. The safety officer must have the ability to communicate with all first responders, safety personnel and officials on the course.

C. Feeding Stations

Feeding stations are an essential part of all open water races over 5K because of the need to maintain hydration.

Minimum Requirements:

- 1. For races less than 5K, no feeding stations are required.

- 2. For unescorted races of 5K and longer, there must be a floating or stationary feeding station available every 2K.

D. Course Evacuation Plan

Each race site must have an approved course evacuation plan to get all swimmers and race personnel off the water with steps in place to address all potential emergency situations.

E. Medical Services

All open water races must have a medical and emergency services plan as part of the safety plan for the race. At a minimum, this plan must include:

- A physician on site with experience in providing medical care in endurance events (e.g., marathon, triathlon) and the ability to use the medical equipment described on the medical equipment list included below;

- One Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) per 150 participants;

- One ambulance on site or within a five-minute response time per 250 participants;

- A cooling or heating tent on site, unless the sanctioning body approves otherwise;

- A protocol for air evacuation if a hospital emergency room is more than 30 minutes away;

- Medical equipment as provided on the medical equipment list included below.

First responders must have the following training:

- Basic life Support (BLS) level CPR and first aid;

- Swimming ability that will allow the first responder to keep the athlete safe until further rescue/medical help is available; and

- Ability to use communication equipment and/or pre-agreed hand signals to begin emergency action.

F. Accounting for Swimmers

It is mandatory for all races to have a swimmer check-in prior to and immediately following each race. Races should consider using a “funnel in” before and “funnel out” system after the race in order to help ensure that all athletes are accounted for. All swimmers must comply with the accounting system adopted for the particular race.

All races must be able to account for all athletes who enter the race, compete in and finish the race. All athletes must be given a race number and have that number written on their body by a representative of the organizing committee.

G. Technical Meeting

The following minimum safety information must be presented at all technical meetings:

- course layout

- feeding stations

- rules of the swim

- water conditions

- marine life

- weather conditions

- the safety plan

- emergency situations

- the safety communications plan

- the evacuation plan for clearing the race course

- safety craft

- emergency phone numbers

- local hospitals

Organizing Committees are strongly encouraged to hold the Technical Meeting for all participants and coaches the day prior to the race in a venue appropriate for effective communication.

An athlete who is competing in the race must either attend the Technical Meeting or have his/her representative attend the Technical Meeting. If the athlete or his/her representative is unable to attend the Technical Meeting, he/she will be required to receive a special briefing in order to ensure that he/she has been informed of all important safety factors for the race. All races must also include a pre-race safety briefing to be conducted immediately prior to the race.

All athletes are required to attend this briefing.

H. Safety during pre-race warm-up and post-race warm-down

Race organizers must take precautions to keep athletes safe during pre-race warm-up and post- race warm-down. Specifically, no swimmer should be allowed to enter the race course prior to or following the event without an escort kayaker, paddle boarder, etc., or the race host needs to offer course monitoring and safety during set training hours. Race courses should be closed to boating traffic during designated training hours.

Part 3: Other Requirements for Open Water Races

A. Water and Air Temperature

Specific rules must be adopted in relation to water and air temperature for open water races.

Race officials must monitor water and air temperatures and water conditions throughout the race in order to maintain a safe environment. One hour before the race, the safety officer must record, post and announce the water and air temperatures.

Requirements:

- 1. If the water temperature is below 16 C (60.8 F), no race can be held.

- 2. For races of 5K and above, if the water is above 31 C (87.8 F), no race can be held.

- 3. If the air temperature and water temperature added together (in Celsius) are less than a total of 30, no race can be held.

- 4. If the air temperature and water temperature added together (in Celsius) are greater than 63, no race can be held.

B. Water Quality

Water quality of a race must be considered in two phases:

- 1) the anticipated water quality, based on reliable data, when the sanction is requested; and

- 2) the water quality on the day of the race.

Requirements:

1. For the location of each swim, local municipality water rules shall apply. If the water quality meets the standards of the local testing authority, the water will be deemed acceptable for the race, unless otherwise determined by the safety officer. The organizing committee must have a certificate from the local authority stating that the water quality is acceptable, issued within 48 hours of the start of the race.

2. If an exceptional event which may affect water quality occurs (for example, heavy rain or flooding), the safety officer (race referee or race director) shall have the authority to postpone or cancel the race.

C. No Requirement to Participate in Specific Open Water Races

There shall be no requirement for any athlete to participate in any particular race of an open water series, including those that are a part of the FINA Open Water World Cup and Grand Prix series, in order to receive final point standings or prize money in the series.

Part 4: Other Recommendations

A. Tracking Swimmers During Races

It is strongly recommended that responsible federations work toward a solution of using a

tracking device that is able to work in water (for example, sonar or possibly GPS) in order to

help track athletes in open water races.

B. USA Swimming Support for Open Water

1. USA Swimming should hire a full-time person to manage open water administrative tasks.

2. The Commission recommends that while giving consideration to the timing and the quality of training opportunities which particular international open water competitions provide, USA Swimming establish a calendar of those open water events which will be supported by USA Swimming coaching and/or support staff. For those events for which USA Swimming will not be providing support, the Commission recommends that USA Swimming attempt to obtain safety-related information from FINA and the race organizer and make that information, together with a safety checklist, available to any U.S. swimmer who chooses to participate in that event with a personal coach or otherwise. If FINA requires the presence of a coach or other representative designated by USA Swimming as a condition of an athlete’s participation at a race where USA Swimming was not otherwise planning on sending a representative, then the cost of sending that representative will be the responsibility of the athlete.

C. Medical Screening of Athletes

For any open water competition where the swimmer is entered by USA Swimming, that swimmer must annually certify to USA Swimming that he/she is medically fit and adequately prepared for the race given the anticipated conditions.

Equipment List (Minimum)

- Pocket face mask to allow rescue breathing without contamination

- One rescue flotation device for each first responder

- Mask, snorkel, and swim fins readily accessible

- Binoculars

- Radio and workable mobile phone

- First aid kit to include supplies for lacerations

- Cardiac defibrillator

- Asthma inhaler/bronchodilator

- Diphenhydramine (for example, Benadryl)

- Benzodiazepine medications for treatment of seizure

- Epinephrine pen

- Intravenous fluids (including ability to rapidly cool with chilled IV fluid in hot weather)

- IV needles/equipment, including large bore (18-20 gauge) needles

- Oxygen with masks

- Glucose tablets

My contemporary notes from January 2011 poising the questions that FINA needed to answer:

This week, the FINA Bureau will gather in Frankfurt to consider the most important item ever to land on its desk: the death of an athlete on the international federation’s watch. The meeting will take place with the 2011 FINA open water circuit under way, an uncomfortable situation to say the least, particularly with a UAE event still listed on the current circuit as ‘TBC’. Contracts are in place and necessary legal cautions are in place, we are told, though such things prevented neither an 11th hour switch of race venue nor the most tragic outcome in the history of FINA competition.

In the wake of marathon swimmer Fran Crippen’s death as he raced for the USA off the coast of Dubai at Fujairah on October 23 last year, FINA appointed a task force of experts to conduct an inquiry into the tragedy.

A second inquiry is also underway, one set up by USA Swimming, with senior IOC and WADA representative Dick Pound in the chair. The two inquiries are running in parallel but may not consider the same issues.

Time will tell how deep the inquiries delve. For the time being, there is a widely held belief that FINA will stick to the more clinical details of the tragedy and make recommendations accordingly, with potential rule changes in open water swimming extending to at least some of those demands made by world-class swimmers in an 11-point plan sent to FINA. The US report may look deeper into areas that FINA has traditionally shied away from at times of crisis: self-analysis of the kind many believe essential if FINA is going to make meaningful change that results in it being an organisation fit to run five Olympic sports in the 21st century.

Take these words from one of those close to events on that fateful October 23: “FINA is still using systems and management styles used years and years ago and long-since replaced by better ways of doing things. They have taken advantage of the relative safety of running events in the controlled environment of the swimming pool and have ignored what’s going on in the rest of the sporting world with risk management. There’s no excuse for that. Given that’s the case, this [tragedy] was going to happen somewhere, sometime. The only surprise is that it hadn’t happened earlier.

“The open water environment is not a ‘closed’ environment and FINA have had their management lapses exposed at the greatest possible cost.”

FINA has had 20 years to get it right after adopting open water as the fifth stall in its stable of aquatic sports and organising the first world title race held under its name in 1991. It is reasonable to ask – so what went wrong?

No one in FINA or the wider aquatic sports world would have wished to see the events of October 23. All would surely wish that they could turn the clock back and FINA is on record as stating that it intends to get to the truth of the matter.

Nonetheless, some of what follows will, without doubt, make difficult reading for some who represent FINA, for FINA itself and federation officials (not to mention the most important people in this whole sad state of affairs: the Crippen family). If officialdom is displeased, so be it, for while under the terms of contract it may be possible to walk away unscathed from the likes of crippling debts of Rome, Montreal, Guayaquil and others down the years, it may be possible to still list the GDR on the roll call of FINA Prize winners for its splendid contribution to the Sporting Crime of the 20th Century back in 1986, and it may be possible to behave in other ways that hardly do a fine job of presenting the best image of FINA to the world, it is neither possible nor acceptable to dodge a FINA Constitution that obliges all who have a vote in FINA matters to “govern and administer” FINA and obliges the Federation to “take part in the technical preparations and in the conduct of … FINA events”.

The purpose is not to single out, to name and shame, though names of officials and others are raised where it would be impossible not to do so in pursuit of truth, understanding and a way of making sure that Fran Crippen’s death is not only the first in FINA competition but the last.

What follows is a bird’s eye view of the week that led up to events in Fujairah, what happened on that fateful October 23 and the immediate aftermath of the death of Fran Crippen. It is neither a fictional account nor one that leans on supposition. It is how things panned out according to witnesses who, at least for now, choose not to be named at a time when inquiries are underway and, where appropriate, have seen these words prior to publication and approved them as a fair and accurate account of events.

In order to be as constructive as possible, we break the report up into four key timeframes and deal with each in terms of

- the scene

- the big issue(s)

- the questions that FINA must find answers to.

Below, parts 1 and 2 relate to the week before the tragic race, while parts 3 and 4 relate to the tragic day of racing and its aftermath, before we provide a list of recommendations supplied by experts and witnesses to events in the UAE.

We make no apology for the length of this file, the issue far too serious to pander to a market that needs to digest the news in its coffee break.

PART 1: UAE PREPARES TO HOST FINA 10KM WORLD SERIES FINALE

The Scene:

The race on October 23 was supposed to have taken place in Sharjah. Well before the event the location was moved to Abu Dhabi. Patronage of events in the UAE is sought from the local Sheikh, such patronage usually involves either a financial contribution or the provision of facilities and services required for the event at no or minimal cost to the organisers. Neither the Sharjah nor Abu Dhabi Shiekhs were able to offer patronage for various reasons, with the decision from Abu Dhabi only coming through in the week of the event. There was nothing left to do but to find an alternative venue – or cancel. FINA’s call. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed Bin Hamad Al Sharqi, Crown Prince of Fujairah, stepped in and served as patron to the UAE round of FINA’s event. Fujairah is about a two-hour drive east from Dubai on the Gulf of Oman.

The Big Issue:

When world-class sports events are staged, contracts are put in place well in advance. Those contracts, presumably, include provision for things going wrong and penalty clauses that cover such eventualities as a host wishing to drop out of a commitment at any time, let alone the 11th hour. Imagine what would have happened if we had all turned up at the Foro Italico in summer 2009 only to be told that actually Rome had changed her mind and the venue for the world titles show was to be somewhere across town, a long way from pre-arranged hotels for athletes, officials, media and any fans and families who had planned a trip in support of swimmers. Of course, the open water circuit involves far fewer people and is far more flexible in terms if the logistics and size of the event. There are times when events have to be moved – but protocols and procedures for such occasions must be put in place and controlled by the title-holder: FINA. The federation must take a hands-on approach in the staging of its events.

The Questions that FINA must find answers to:

- Was FINA aware of the problems in the UAE and if so how long in advance?

- Did FINA consider cancellation of the event?

- In a year in which the UAE had already torn up the contract to host the 2013 FINA world championships in five Olympic sports, did FINA express any concern to the UAE over the 11th-hour change of venue for an event bearing its names and the title “World” – and if so, what was the response and what action and decisions resulted from that response?Were phone calls made to the would-be organisers to impress upon them the need to honour commitments?

- Did FINA make any demands of the hosts of an event held under their name and call for responsibilities towards athletes to be honoured?

- Did FINA get involved in or ask to be kept up to speed on all changes to arrangements for travel, hotels, the race course, feeding pontoons, safety measures, monitoring of conditions, training facilities?

- Did the man in the UAE for FINA, Valerijus Belovas of Lithuania and a member of the FINA Technical Open Water Swimming Committee, speak to organisers about the switch in venue and what were his instructions from FINA HQ?

The references to the man in UAE for FINA could equally apply to many other situations at events around the world in terms of questions of authority, roles and responsibilities

The Scene:

Local contractors and volunteers, native to UAE as well as overseas experts on the ground there, were drafted in to help Fujairah in its efforts to accommodate the athletes, and provide transport for them. The first coaches and athletes knew of any switch of venue was a mention of the “possibility” of such a thing as they arrived at Dubai and Abu Dhabi airports. There was confusion and uncertainty for a while before final arrangements for a switch of venue had been made. A fair few of those returning to the UAE for open water racing had lodged concerns and complaints the year before about the UAE round of the FINA competition in terms of the lack of pre-race information and some aspects of organisation of the race, including safety related issues. One team delegate would later say: “FINA representatives were at the two other events held in Dubai and [other venue in the Gulf] last year when safety issues were raised. They must have approached this event knowing that safety was an issue of concern. I and others have stood up at meetings before and raised concerns and been shot down in flames.”

Against that backdrop, the switch of venue was unpopular on one level but not on another level among athletes, coaches and managers. Despite the 11th hour changes and all that would come to pass, many have expressed a view that the arrangements for bussing them from one venue to another and the standard of hotels and food then provided was excellent, far better in fact than swimmers, coaches and managers had experienced at other stops in other countries on the circuit.

The Big Issues:

Complaints had been made about the UAE round of the FINA series in previous seasons and yet FINA was about to stage an event under its auspices and those of its member, the UAE Swimming Federation, without tests, protocols, relatively regular site visits, the construction of risk-management strategies pertinent to the new venue and other pertinent topics being discussed, it would appear to many. The lead-in time to the event was a matter of days and some who worked on the event were called in to help in that very short time frame.

The Questions that FINA must find answers to:

- What discussions were held between FINA and organisers in the UAE to ensure that complaints made and concerns lodged about previous open water events held there were addressed and appropriate changes made?

- Did members of the FINA Technical Open Water Committee make the problems known to the FINA Executive and/or the FINA Bureau, and if so, were those issues discussed and what decisions were taken as a result?

- How soon before an event is staged is it reasonable to have a working events team in place and briefed on all aspects of the competition and related logistics?

- How many of those drafted in to help and part of the organisation of the event had a good command of English, the official working language of FINA?

- Was there a problem with lines of communication?

- What role was played by Valerijus Belovas of Lithuania, a member of the FINA Technical Open Water Swimming Committee sent to represent FINA in terms of playing a hands-on, active part in ensuring that the rules of the international federation would be observed on race day, that conditions were appropriate, given the late change of venue – and did he or anyone from FINA approve the new course and venue and if so how soon in advance of the race on October 23?

- To what extent did the FINA Executive and Bureau get involved in that process and were lines of communication between the FINA representative on the ground in the UAE and those in positions of high authority in FINA open and active?

The nature of the link between those who govern FINA and those who represent FINA and the flow of information between the two and the role of the relevant technical committee and what happens to any recommendations that it makes is an important aspect of any change that improves the working practices in FINA in the future.

PART 2: THE DAY BEFORE RACING

The Scene:

Swimmers, coaches and managers arrived at the pre-race technical meeting conducted by FINA to find that the briefing was to be run by an efficient local resident associated with the Swimming Federation who had been drafted in at the last minute and was asked to take charge of proceedings. The briefing took place outdoors at 6pm, but even at this hour the temperature was still uncomfortably high (around 33C) as it usually is in the UAE in October. While the meeting followed an established order, and cold water was supplied, the location, the lack of light and the heat meant that the athletes in particular were anxious for it to finish. It should be noted that there was no procedure to check athletes and coaches in or out of the meeting to ensure they had received all the required information, as is common in other sports which hold safety briefings. After the introductions of the officials, being Valerius Belovas (FINA Open Water Swimming Committee), Mohammedou Diop (FINA Medical Committee), Saeed Al Hammour (Secretary General of UAE Swimming), Ayman Saad (Executive Director of UAE Swimming), those gathered watched a video about Fujairah (not on the technical aspects of the venue but about the tourist destination). Following the video each of the swimmers was named and their numbers allocated. Mr Osama Al Shasli, the Technical Coordinator for the event was then introduced to provide the technical information about the course, the location of pontoons, and the safety provisions.

At this stage many of the swimmers, including those from the US, chose to leave. They were urged to stay by the person running the meeting (not a FINA representative) but chose not to and left early, prior to the completion of the safety briefing, and before any concerns about safety, conditions and water temperatures were discussed and questions taken from those assembled. Fran Crippen and some of his teammates were among those who left early, missing the main briefing for the race. That point is later made by some at the meeting for an event to which USA Swimming did not send an official manager to speak for swimmers, to raise any issues that might have been pertinent to the safety and welfare of athletes or organise feeding and feeding positions on pontoons for the US swimmers. Jack Fabian, father of swimmer Eva Fabian, was present but not there in any official USA capacity, nor, as a man alone, could he possibly have been expected to monitor the needs of the entire US contingent. Documents and witness statements testify to the fact that Mark Schubert, former head coach to the USA, raised the issue as early as 2008 of having open water swimmers representing the US being accompanied by staff with knowledge of the open water environment.

At this point in the technical briefing in Fujairah, after many swimmers had left the scene, some coaches and managers posed questions on the course and safety and asked for two feeding pontoons to be used and for the second one to be increased in size. There was also some concern over the fact that the second pontoon was not covered – and therefore not a good place to be for three hours in the heat of the day. The layout of the course was triangular, from starting point a 750m leg to the first buoy, then another 750m stretch and then one of 500m back to the starting point. There was no pontoon on the last leg of the triangle. Those gathered were assured that there would be safety boats out on the course but there would be no boat to take coaches and others back and forwards from pontoons to shore during the race (those on the pontoon had to stay there throughout). At that point, one of the organisers called for questions to be brought to a halt because things “could go on all night”.

Belovus then spoke briefly about the event but his contribution was limited and one witness to events said: “I can’t even remember what he said, and I found it difficult to understand him.” Belovas would later also be described as a man who “was there but was not running anything … he was a bystander”.

An anti-doping briefing was provided after the course layout information, but witnesses have reported that they could not understand what was being said by a man whose native language was French and who had a poor command of English, the working language of FINA under its constitution. There were several witnesses who also noted that the English spoken by the race referee was not good enough for coherent comprehension. Witnesses have also noted that the person who ran the technical briefing had exceptional command of English and did a fine job, which included an attempt to interpret the answers being provided by “experts” so that what those experts were saying could be understood by the majority of those gathered.

A few more questions were put after the Anti-Doping Briefing but while some believe that most people “seemed reasonably happy” at that point, the following are comments made by witnesses to the technical meeting there on the day and aimed at FINA and its handling of the situation and the sport:

“At the technical meeting, among questions raised were safety, water temperature, shading for swimmers. Those concerns were all but swept under the carpet by officials and we were left not knowing where we stood. I felt so sorry for the American coach who had so many swimmers to watch. It should not have been for him to have to do that. Organisers should have been watching every swimmer.”

“FINA representatives were at the two other events held in Dubai and Abu Dhabi last year when safety issues were raised. They must have approached this event knowing that safety was an issue of concern. I and others have stood up at meetings before and raised concerns and been shot down in flames.”

The witness then names representatives of FINA and LEN commissions and describes them as “yes men who just say ‘yes’ to organisers because they want to be on the next trip … a whole cultural change is needed.”

“I’ve been shocked about the difference of professionalism in pool swimming compared to open water. It’s tragic that it has taken the death of someone to change things but all we can hope is that Fran did not die in vain and that the concerns of many in the sport will be taken seriously by those who run the sport.”

The Big Issues:

The wisdom of holding technical meetings in anything other than an environment fit for professional discussion is one that needs serious consideration. The lack of provision of boats that could be called on to ferry people from position to position should such movement be necessary and desirable is troubling. The desire to close down questions when the heat is on at FINA events has been witnessed on many occasions and in many a varied circumstance: many believe that it is a habit that ought to be removed from the world of FINA, particularly when it extends to moments when issues of safety and welfare of athletes are being raised. The fact that concerns over safety had been raised in previous years in the UAE is troubling and many would assume that an 11th-hour shift of venue would have reminded FINA to be all the more cautious in its handling of the Fujairah race and in addressing any concerns of officials, coaches or swimmers raised on the eve of racing.

When FINA holds events, it is widely assumed that FINA people are running the show with local organisers and have the authority to say “stop”, “go”, “change this, that or the other”. It is assumed that official functions for organising events are filled by people who have been appointed well in advance of an event under terms of contract. It is assumed that all those who will represent FINA and speak to athletes, coaches and managers will have a solid command of English, as dictated by the FINA Constitution. In Dubai at the world short-course championships, the top table at the technical meeting was heavy with native English speakers and others whose command of English was exceptional. On that occasion, there could have been no excuse for misinterpretation on the part of the audience of coaches, managers and some athletes.

The Roles of National Federations And FINA

One of the issues that has been brought to the public’s attention by the death of Fran Crippen is what the swimmer himself campaigned to have changed back home in his domestic swim federation. Fran Crippen contributed several thousands of dollars towards the costs of getting around on FINA open water circuits.

Fran Crippen and teammates were often unaccompanied, travelling without official representative at technical meetings, without dedicated people responsible for their feeding and general welfare, without open water experts on the water come race day. Two issues arise. The first is the obvious decision that federations have to take: to support open water as a sport or not, and then to decide which events it is prepared to support and state clearly those events to which swimmers travel and compete as natives of their country but without official selection or support from their nation or federation. The second is FINA’s role as guardian of activity that has grown at an unprecedented level over the last decade, with quantity often winning a battle over quality.

If swimmers need officials to represent them and to feed them and care for their welfare and federations cannot or will not supply such care, attention and the funding required, FINA must decide: take responsibility and appoint FINA officials to those roles, or cancel the activity because basic safety and welfare standards are not being met. It is not good enough for domestic federations to send teams out into the world with no funding and no support and yet give the impression of official backing by virtue of the flag flying on the swimmer’s back.

It is not good enough for FINA to keep boasting the worth of activity if it is not prepared to put the necessary infrastructure, including risk-management strategies, and funding in place. Nor should FINA stay wedded to an attitude that its only role is to grant the right to host events held under its name, while organisers bear the costs and responsibilities.

The likes of Long Beach, California, and USA Swimming have the tools to get the job done without too much help from FINA, though they are not prepared to pay the price in dollars that FINA demands for granting the rights to hold a world championship. On the other hand, many of those now winning international bids from international sports organisations chasing the dollar (Dubai, Delhi, Qatar and so on) rely very heavily indeed on overseas expertise and experience to get the job done (and even then, for reasons of cultural remoteness from the sport they want to host and perhaps be a part of, they may well fall down on the job).

By failing to stare the resulting problems in the face, federations both international and domestic are contributing to an image they wish to embrace of an Olympic sport thriving and growing while at the same time keeping quiet the fact that the sport only exists beyond the Olympic Games and FINA World Championships (five sports) because swimmers pay their own way, put up with appalling conditions (be those in the water or back at the hotel or in the snack bar) and have their opinions fall on the deaf ears of people who at times appear more interested in their own meal ticket to the world of sporting globetrottery than in the interests and welfare of athletes.

The Questions that FINA must find answers to:

- What conditions are laid down for technical meetings in terms of the setting and circumstance of such gatherings?

- Why was there was no procedure to check athletes and coaches in or out of the meeting to ensure they had received all the required information, as is common in other sports which hold safety briefings?

- Why was the issue of number of feeding pontoons left to the eve of racing? Is that not something that ought to be in place weeks in advance, long before swimmers even travel?

- Is it wise to have any stretch of water between buoys left without a pontoon from which to feed and observe? What provision, if any, is made in the rule book for distance between feed stations and observation points ?

- Is it wise to place officials (from many climatic zones) on uncovered pontoons for three hours in temperatures of 40C plus knowing that there is no provision for ferrying them back and forth during that time?

- Why did one of those organising the event think it appropriate to stop questions at the technical meeting when the questions being asked were of serious concern to officials and coaches representing the same interests as FINA: the athletes?

- Were questions ‘all but swept under the carpet by officials’ and were coaches and managers ‘left not knowing where’ they stood?

- What discussions were held and actions taken by FINA in the wake of concerns expressed over safety at UAE events in previous years?

- Did the FINA representative at those events take the concerns back to FINA, file an official report that highlighted them? And if so, what became of that work?

- Is it the case that team representatives have ‘stood up at meetings before and raised concerns and been shot down in flames’?

- If so, who shot them down in flames, why and whose interests were served?

- Why did no-one in Fujiarah that day feel empowered enough to say “stop – we will not race without X, Y and Z being in place, without the race changed to such and such a time, etc”?

- Are FINA delegates ‘yes men who want to say yes to organisers because they want the next trip’? If some are, is that cultural and systemic, does it flow top down, or is the accusation levelled at a few who are failing FINA and whose approach is deemed unacceptable by the FINA Bureau and Executive at the helm of the Bureau?

- How does FINA regard that serious charge levelled against those it sent to represent it in the UAE?

- Is there a gulf in the level of management and professionalism in pool swimming and other corners of the FINA world – and if so, what does FINA intend to do about it?

- If FINA sends a delegate as the main man representing the federation at an event bearing its name and the word “world”, what responsibilities does he have?

- Must such an official have excellent command of the official language of FINA, namely English?

- As a member of the FINA technical committee of experts, was Valerijus Belovas of Lithuania, a member of the FINA Technical Open Water Swimming Committee, not the perfect man, indeed the only man, who ought to have run the technical meeting? And if so, why did he not do so?

- Is it standard procedure NOT to use the people appointed as experts to help FINA manage the sport professionally come the critical moment when someone must give the “all-clear – ready to roll”?

- Is it standard procedure to rely on local volunteers to perform such roles – and if so, how are such people chosen and who chooses them?

- Are appointments to key positions made by people with the best possible knowledge of the sport and event at hand?

- Is it obligatory for anti-doping officials, race referees and others sent to represent FINA and organisers and talk to swimmers and coaches at events carrying the title “world” to have a strong command of the English language?

- And if so, why was that not enforced?

- If not, how does FINA intend to solve a clear problem of communication at the most critical moment of any event, the very moment when knowledge of logistics, safety protocols, race arrangements, anti-doping procedures and so forth are being passed on?

- Was it the case that a local volunteer – who did have excellent command of English and very good experience of sport and sports events by all accounts – was drafted in to run the technical briefing at the 11th hour?

- Had no provision been made for that role well in advance of the week of competition?

- What part did FINA play in appointing volunteers to positions of responsibility?

Which takes us to the tragic events of October 23:

PART 3: A RACE DAY THAT WOULD END IN TRAGEDY

The scene:

The next morning, race day dawned with swimmers taking the plunge and noting that the water was ‘warm but OK’. The race referee was Osama Al Shasli, head referee from UAE Swimming but a man who does not appear on the latest FINA list of approved open water officials, a list that does include four other men from the UAE.

Fran Crippen is reported to have noted that the water was warm but said that was ‘good’ because he liked it warm. Such comments are merely passing remarks, of course, to be heard from swimmers in training on many occasions, for warm water is perceived as being “comfortable”. Not over 10km at the speed at which world-class swimmers swim, however – and not everyone was happy before the race, it ought to be noted. This is the statement of a world-class swimmer: “From my perspective, before racing and before anything happened to Fran, I had a feeling that something terrible was going to happen. The day before the race, we trained at 4.30 or 5pm, which was later in day than the lunchtime race was to be held. I got in the water and remember thinking ‘this water is so hot’. I swam about 700m and got out and said to [coach] ‘is there a maximum temp in FINA rule’. He said he wasn’t aware of it but would find out. I said to him that I honestly thought there should be because this water is just too hot. I rang my father and told him that I thought something bad is going to happen. When we swam in there the day before the race, the thermometer reading in the coolest part of the course, where we started, read 33C. But when we got out on the course there was a wall of heat. You could see the haze shimmering off the water at that part of the course. That’s what it was like where they found Fran. I just remember getting out of training saying ‘this water is too hot’.”

The swimmer then noted that if the pool waters in training back in a home programme get up to 29C all swimmers complain that they cannot cope. “And what people have not yet picked up on is that we were swimming in salt water out in Dubai. Not only were we out in midday sun in boiling water but we were getting very dehydrated from having salt water in our mouths. I could hardly speak after the race, it was so bad.”

There is a little discrepancy in the water temperatures that witnesses have provided, the figure varying between 29C and 34C, with many agreeing that the thermometer attached to the pontoon at the start of the race read 31C. There was no monitoring of surface [ambient] temperatures, however, and one official has subsequently said: “There has to be a recommendation for an upper limit to water temperatures. It was 31C as the race went off. But no way was it that at the surface, and of course, they were all in swimming caps as well. It was very, very hot.”

THE RACE:

The PA wasn’t working on the call down to the water at the start of the race. But things got underway, men going off first, then the women. There were a couple of safety boats for each race, though the term ‘safety’ is not stipulated. It is assumed that their role is to follow the swimmers but, again, it is not stipulated where the boats should be and how many swimmers ought to be observed by each boat. One of the boats was the lead boat, contrary to reports that suggested there was no lead boat. A witness said: “The police boat looked like it was doing nothing but it had sonar and was active.” None of those roles or functions had been explained to the touring teams and many swimmers and coaches would later make statements to the effect that there were too few boats and those that were on the water ‘did nothing’. It was not quite the case, though serious issues over the quantity, quality, structure and management and form of surveillance have been raised by the Fujairah race. There are technical questions too, with some noting that jet skis are somewhat useless is they are not accompanied by a rescue board on which a struggling swimmer can be placed.

One witness said: “You need a rescue board hanging off the back of it. A swimmer cannot climb on to a jet ski out of the ocean, nor can the person steering the jet ski carry a second person. You also need surf skis (canoes) so that swimmers can lean on them if they need to, also surf skis are at water level and can more closely monitor a swimmer than a jet ski rider can.”

Some two hours or so after the race, it would be discovered that Fran Crippen died somewhere on the last 500m stretch before the finish point. A witness, breaking down when speaking, said: “It was in the last leg that they found him. He had gone round the last buoy and an official saw him. He went down not long after that buoy. The official noticed that he was not looking at the pontoon ahead [the finish] but back at the buoy and he looked confused.” Fran Crippen died soon after, the precise cause of death yet to be revealed as part of inquiries being conducted by FINA and an independent team on behalf of USA Swimming.

The initial autopsy was written in Arabic and no professional translation service was conducted at the time events were unfolding in the immediate aftermath of the swimmer’s death. We also know that no official count of athletes emerging from FINA open water races took place. The scoreboard at major events indicates the count, of course, but the exercise of counting them in is not part of official procedure.

At the end of the race, several swimmers needed medical attention and some were taken to hospital by ambulance. The drivers of those vehicles in the UAE are, in most cases, just that: drivers. (In some countries, those drivers would also be trained medical staff, such as paramedics).

Of the field, all but one swimmer made it to the finish, 81 swimmers in all. A big race and a number that has raised questions of limits and/or changing the nature of race formats and the extent of provision for safety, vigilance and on-hand nursing and medical provision and facilities. Christine Jennings (USA) was among those who emerged from the race in a poor physical condition. She had waved for assistance on the last leg and had rolled onto her back to rest. By the time a jet ski arrived to offer assistance she had decided to swim to the finish. She was taken to the ambulance but decided she did not need their assistance and was helped back to the air-conditioned tent. A volunteer who happened to be a trained first aider but was not at the event in any medical capacity saw Christine try to walk to the tent, and offered assistance. Christine was taken to the tent, laid down and given ice and cold water to cool her down; her pulse and respiration were monitored by the first aider. After some time the first aider strongly urged her to go to hospital as she felt her recovery would be faster if Christine were to be given medical attention. After further strong encouragement to go Christine agreed and despite having a stretcher there chose to walk to the ambulance.

One witness was taken aback by the lack of trained nurses and medical staff available at the scene of the race. One witness noted the reliance of luck at FINA open water events when saying: “Everything was running fairly smoothly but it was disorganised. I’ve competed in [other sports events] and they ran smoothly because they were well-organised. This was a case of running smoothly at the surface to the point where you needed good organisation to kick in.”

About half an hour after the race Chad Ho was overheard discussing his overall finishing position in the race and joked in the banter common among competitors that ‘at least I beat Fran’. It was then that Fran Crippen’s teammates asked: actually, where is Fran? The frantic search that ensued by Alex Meyer and his teammates is well documented. The timing of events is still hazy. It was at least another half an hour after Fran’s absence was noted before officials were notified that he had not finished. The organisers immediately sent the jet skis out to search but seemed convinced that Fran had chosen to go straight back to the hotel or had gone to the hospital without notifying anyone. One witness noticed that effort had been put into contacting the team hotel and the hospital to which other swimmers had been taken, even though it should have been obvious that Fran Crippen had not passed the posts he would have past had he emerged from the water and would not have left the race scene without his teammates.

When searches at hotel and hospital failed to locate the swimmer, that is when “the panic level was starting to rise”, said a key witness. Organisers were urged to get more boats out on the water to comb the racecourse methodically. The question overheard to have been oft repeated was: why are there not more boats out there searching? Valerijus Belovas was asked the question. He was seen to shrug and heard to say ‘there are supposed to be five’. In fact there were four. Efforts were made to get organisers to use the media boat to join the search but one witness said: “There was no response on that. It was really disorganised. It made an impact on everyone there. There was a feeling of hopelessness and a belief that no-one knew what they were supposed to be doing.”

The result was that swimmers took the plunge, the risk being that it would be swimmers who might end up fishing Fran Crippen’s body out of the water. “That’s not what we wanted,” said one witness. “We did not want them to find him. They had also been in that 10k race, they were exhausted, drained and emotional.”

Some managed all too well to control their emotions at that stage. Witnesses watched as Valerijus Belovas was urged on several occasions to take control of the situation. One said: “He was just standing there, arms folded, watching, not doing anything at all.” Belovas was overheard saying that it was not his responsibility but the responsibility of Ahmed al-Falasi, president of the UAE Swimming Federation. Whatever responsibility the UAE federation held and holds, the truth was that Mr Al-Falasi was not even present at the scene at that time, although he had been seen there earlier in the day – yet still the main FINA man said: no, not up to me. It seemed to some observers as though the highest authority of FINA at the scene was frozen and unwilling to get past his position of “all down to organisers, nothing to do with FINA” and “we have followed the rules”.

The language barrier exacerbated the feeling of disorganisation and frustration as all communication at that stage was in (very heated) Arabic and even the English-speaking volunteer who had run the technical meeting could not get the information needed to relay it to the concerned swimmers and coaches present. If proper procedures had been established, such confusion would not have occurred.

It was left to swimmers and coaches to raise the question of a helicopter and a local volunteer then approached the police to ask for one to be sent in. The volunteer also ran across to the neighbouring Marine Club to ask if they had a helicopter available. No provision had been made to have a helicopter placed on standby, for no risk-assessment strategy existed. It was left too to local volunteers to try to persuade swimmers to get on buses so that they could be taken back to the team hotel. Many did not want to move from the scene.

Something like two hours after the race, UAE Swimming officials were seen running towards the dock area 200m away from the finish line, as the Police Boat started to head back to the dock. A volunteer tried to get the way blocked so that swimmers could not gain access to spare them the reality of what was unfolding. Alex Meyer was among those who pushed past so that he could find out what was going on. A large group of local people who had nothing to do with the race gathered as local volunteers screamed at them to go away. Alex Meyer was overheard delivering the news that Fran Crippen had died.

Ayman Saad, the Managing Director of the UAE swimming federation, would later be criticised for using these words: “We are sorry that the guy died, but what can you do? This guy was tired and he pushed himself a lot.” Some of those there on the day have been keen to note that the man was truly devastated. His choice of words was unfortunate to say the least – and he was not alone. Some FINA officials made similar statements when they ought to have been silent.

A swimmer from the Fujairah race would later say: “As an athlete you don’t ever want to be racing when your welfare is compromised. Open water is quite hard anyway, with tides you have to fight against, jellyish and other things … but when the temperature is too high or too low, you go into the race with apprehension. You never want to start a race of any magnitude with apprehension in your mind. From my personal perspective, when racing, Fran was second in the ranking and there was a quite a lot of money at stake for him to finish the race and win prizes for the whole tour. I have been in situations where if I had not been as competitive and driven as I am I would have pulled out of races. You get a niggling at the back of your mind that keeps you going when it might be better to stop.” Did that not highlight the need to have official vigilance of swimmers and appoint officials specifically there for the task of stopping swimmers who looked like they were struggling? “It’s a really good point and one that I don’t think people have ever thought about before,” said the swimmer. “I’ve been pulled out of a race once but probably should have been pulled out of four or five races for my own good. But for the athlete, you just don’t want to fail and that’s what it means not to finish. We have to learn from this and make our sport the most professional sport it can be and not one where life is at risk, let alone someone losing their life. It was unreal out there.”

Swimmers make money too: one of the things that athletes were talking about at the UAE event, the last of the season, was the money that Fran Crippen would lose if he failed to finish the swim. Among 11 demands put to FINA by world-class open water swimmers is the call to drop a race/prize-money format designed by FINA to ensure a best-of race at the end of the series. The effect of FINA’s current policy is to drive swimmers conditioned to push themselves to the limit and beyond to race on past danger points in events where FINA makes no provision for overriding that nature and pulling swimmers who get in trouble out of races.

Valerijus Belovas would later write: “Organisation of the competition in Fujairah did not differ at all from what I have been observing for as long as 15 years. Organisation of other FINA events was even worse … I would like to emphasize that what happened during the World Cup in Fujairah could happen during any competition. … We need new specifications, requirements to the organization of safety during competitions and it is namely us who have to do this. I am very sorry about what has happened and declare that there were no violations of the competition organization applied in our usual practice during the World Cup in Fujairah.”

In other words he is effectively saying that FINA had made no provision to cope with a crisis that had been waiting to happen. He was sticking to the letter of FINA law and a rule book that does not spell out: when faced with a crisis, roll your sleeves up, take control on behalf of FINA, for this event is under our auspices and we bear responsibility – as such, please do act on FINA’s behalf. A lack of risk-management strategy allows Belovas to reply: act in what way, and how, with what authority? Some witnesses, including the likes of Alex Meyer and others who ran themselves ragged in their desperation to find Fran Crippen might reply: do what your human nature tells you to do – but do something, anything being better than nothing. If Belovas did it by the book, then it is time to throw out the book, many now believe.

Gunnar Werner, the Swedish retired judge and honorary member of the FINA Bureau now at the helm of the task force inquiry run by the international federation, was sent to the scene in the wake of Fran Crippen’s death. He surveyed the scene but witnesses there on the day have complained that no one spoke to them. One said: “I felt like no-one was listening … like he didn’t want to know.”

And what do we make of this comment: “FINA makes money from these competitions but they treat them like a backyard knock-around.”

The Big Issues:

The lack of a risk-management strategy is woeful. The lack of action from the main FINA man was woeful. The lack of warning systems during races was woeful. The lack of adequate vigilance in the race was woeful. The apparent chaos at the end of the race was woeful and more than lamentable. The reliance on willing, local volunteers to think on their feet and try to put in place some facet of management and control on the ground while running, while a disaster unfolded as the likes of the man from FINA stood by, was woeful and unacceptable.

With regards to the future, the apparent lack of action in the face of a view held by many in the open water world, including members of the FINA Open Water Technical Committee, that the sport’s competition circuit suffers from a range of problems is troubling.

Belovas notes: “We need new specifications, requirements to the organization of safety during competitions and it is namely us who have to do this. I am very sorry about what has happened and declare that there were no violations of the competition organization applied in our usual practice during the World Cup in Fujairah.”

In other words: Fujairah was a disaster waiting to happen and happened against a backdrop of warnings that went largely unheeded and did not result in any changes designed to make the differences being demanded by coaches, managers and the swimmers themselves.

The Questions that FINA must find answers to:

- Why was there no risk-management protocol in place?

- How was the race referee chosen and was he listed among the ranks of FINA’s open water approved officials (he is not on the list published in November 2011)?

- Why did the main representative from FINA feel that it was not his responsibility to take control of events?

- What is the legal and executive advice that FINA gives to any representatives when faced with such events as those that unfolded in Fujairah?

- What provision is made for the likes of the official on the last buoy who noticed that something was not quite right about Fran Crippen’s demeanour to sent a warning signal to boats, observers, lifeguards, team staff and medical staff that a swimmer requires close vigilance, with a strong chance of there being a need to pull that swimmer out of a race?

- Are the right types of ‘safety’ vehicles out on the water in open water events?

- Why had FINA never considered the effects of racing 10km in waters over 30C when it places a limit lower than than for pools in which swimmers must swim races just 50m long?

- What attention is paid to temperatures outside of the water and the heady mix of hot water, salt water and ambient heat in the zone swimmers spend two hours pushing themselves to the limit and beyond (the point of the exercise)?

- Did FINA organise instant professional translation of the autopsy report written in Arabic? If not, why not?

- Why wasn’t counselling offered to all present immediately after the tragedy occurred? This is considered an essential part of any accident response plan all over the world, why were the needs of the witnesses ignored so callously?

- Has anyone considered the long-term effect of this on those present? To date, note some of those there on the day and still suffering as a result of the extreme nature of events, this has been completely ignored by FINA.

- How many times has the FINA Open Water technical Committee raised issues that came into the public gaze on October 23 long before that race unfolded?

- Assuming those issues were raised, what did FINA do about it?

- How much consideration does FINA give to local cultures and practices in law, medical provision, including what in some countries is established norm when it comes to ambulances, nursing provision and the like, and other matters when granting bidders the right to host FINA events?

- Should swimmers be placed in a position where, against their better judgment, they race on because FINA operates a forfeit-prizes policy for those who do not finish the last race of the season?

- Should FINA now make sure that no swimmers are driven beyond their limits specifically because FINA’s race/prize format drives them into dangerous waters?

The last part of our report deals with the response to the news that no one wanted to hear.

Part 4: IN THE WAKE OF FRAN CRIPPEN’S DEATH

The Scene:

Information given, quotes (some woeful in their apparent lack of sensitivity) provided by officials in the UAE, a media briefing: all reflected a chaotic handling of events. In the aftermath of the swimmer’s death, at a time when the autopsy report was in Arabic only, journalists not only had difficulty in gaining access to facts but were actually fed falsehoods, the cuttings of the world media tell us quite clearly.

The other troubling aspect of post-race events was the way that US swimmers were handled by the local judicial system. Some felt that they had been interrogated, while the process of form-filling and questioning was onerous and long. That could have happened in any country but questions arise, nonetheless.

The Big Issue(s):

Part of any risk-assessment strategy is how to present information to the media in a coordinated and calm fashion, with regular briefings staged in order to keep journalists up to date with the latest developments. The alternative is to allow scattergun quotes to be delivered by people who either know not enough or know something they’d rather not be known, and for rumours to run wild. Opinion won the battle over fact in the hours after the Fujairah tragedy.

When swimmers attending a FINA event are called on to be interviewed by police, specifically in relation to events at the FINA competition, it would seem appropriate for a FINA-appointed delegate to accompany them, if only as an observer/witness.

The Questions that FINA must find answers to:

- What efforts did FINA make to have the Arabic autopsy report professionally translated before making statements to the media?

- What media protocol was put in place the moment that it was known that Fran Crippen had died?

- Who was appointed to run the media operation specifically charged with handling all calls and questions related to events in the UAE?

- What lines of communication between the ruling FINA Bureau and FINA representatives in the UAE were established?

- What provision does FINA make in case of athletes being called by local judicial authorities in relation to specific race-related events during a FINA competition?

The latter cuts to the core of one of the most important questions facing FINA: where does the international federation draw the beginning and the end of its responsibilities as guardian of athletes during events held under its auspices? Life insurance plans and policies are in place at all FINA events but whatever level that is set at, no amount of money can bring Fran Crippen back and any findings arrived at and recommendations made by the two inquiries underway must focus on making sure that no claim on insurance is required ever again.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Beyond the 11 points raised by world-class open water swimmers in a petition to FINA over the future of their sport, further recommendations provided by experts and witnesses to events in Fujairah:

- No obligation to finish in order to claim prizes won from points collected in previous races

- An upper limit on water temperature and introduction of ambient temperature controls.

- A limit to the number of swimmers on the water at one time; or imposition of a ratio of boats and other safety vessels to swimmers; better instruction as to where safety vehicles should be and how they operate.

- provision of safety craft for stragglers. Use of canoes is common in triathlon and non-FINA open water racing in some parts of the world. A flotilla of canoes should be on standby. Jet skis must be accompanied by rescue boards.

- provision of at least one pontoon on each leg of a race no matter how long that leg is; limit of 750m per stretch on any circuit; maximum distance of 500m between pontoons

- A team representative or FINA official on each pontoon with the authority to withdraw a swimmer from a race, an authority that overrides the will of the swimmer.

- A transponder station on each pontoon not just at the start/finish line) and an official on each pontoon charged with the task of counting swimmers past each point, with the ability to send warning in the case of a swimmer failing to show as expected, the idea is that each swimmer is monitored closely all the way round a course.

- A flag system: if an official/coach/manager spots a swimmer showing signs of distress a specific flag could be used to alert a surf skier that individual monitoring was required for the rest of the race.

- First-aid specialists should be on site at all events (not transport staff but people with specific first-aid training)

- A risk-assessment strategy that includes a rescue plan and clear information about what function is performed by which people and crafts

- Crowd control of events

- A default policy of FINA taking control in the case of crisis.

- All those charges with running meetings, briefings and dealing with teams must have a competent and clear command of the working language of FINA, namely English.

- Translation services on standby in case of emergency.

- Counselling offered to all witnesses to an accident or tragedy.

- FINA must re-assess the licensing fee payable to FINA by the Federations to host these events in light of the extra resources clearly needed to ensure the safety of participants. The primary goal must be the hosting of a safe and successful event, not just the collection of revenue for FINA.

- Beyond the issues raised for the immediate, tragic past and the future of open water swimming, general accountability and the decision-making process, indeed the control of how FINA works, demands scrutiny as a result of the death of Fran Crippen.