For Brian Goodell, Anniversary of Olympics that Weren’t Means ‘Nothing’

For the 40th time since what could’ve been the peak of his swimming career, the last week of July passed by Brian Goodell without much of a thought.

That it’s such a round anniversary since the American distance star didn’t get a chance to defend his Olympic gold medals at the 1980 Olympics thanks to the American boycott of the Moscow Games … it doesn’t much matter to him.

“It’s kind of a nothing burger,” Goodell said by phone this week. “I was looking forward to having the reunion at Olympic Trials and of course that didn’t happen. It’s just kind of the same thing.”

Granted, Goodell has more on his plate these days. The mayor of Mission Viejo, California, a location from which his swimming exploits are inextricable, has plenty to attend to, navigating a town through COVID-19. He’s not even all that connected to a summer without the Olympics, after the virus delayed the Tokyo Games to 2021.

Instead, Goodell has gotten accustomed to a certain level of disappointment surrounding the Olympics. It happened when President Jimmy Carter used the summer Olympians as a political pawn, bullying the United States Olympic Committee into boycotting the Moscow Games ostensibly in retaliation for the U.S.S.R.’s military incursion into Afghanistan the previous year.

Goodell was looking forward to a planned reunion for the 1980 Olympians at the Olympic Trials in Omaha in June, but that was scrapped by COVID. He’s been on Zoom calls with his fellow Olympians, many of whom he remains bonded to by the tribulations of four decades ago, as well as to his former UCLA swimming teammates (another ill-fated program, cut in 1994).

But disappointment has become the norm for Goodell in this arena. He said:

“It’s not really that big of a deal. We didn’t go to Moscow and we didn’t go to Olympic Trials this year, so it’s the same.”

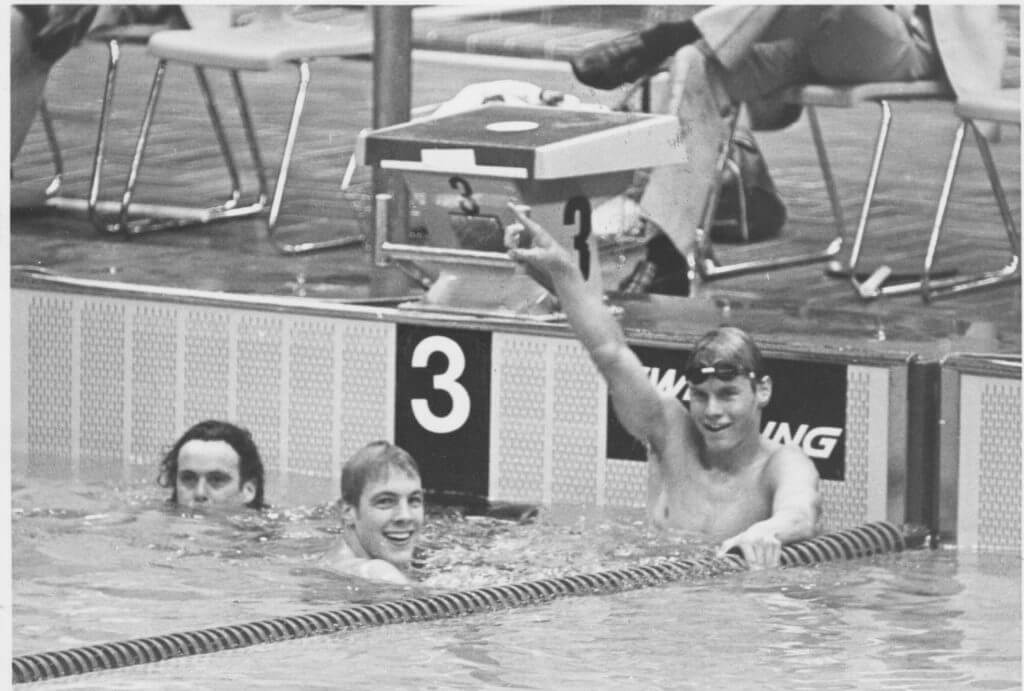

Brian Goodell

The boycott took the sting out of the swimming competition, with the world-power Americans absent. One of the most tantalizing matchups in Moscow would’ve involved Goodell. The storylines were readymade.

On one side was Goodell, winner of gold in the 400 and 1,500 freestyle in Montreal in world-record times, All-American boy from California, wrapping up his career with a second shot at gold.

At the other was Vladimir Salnikov, the home-country hope, an up-and-comer who finished fifth at the Montreal Games in the 1,500. It didn’t take a degree in Cold War studies to understand the hype.

Goodell harbored no particular animosity for Salnikov. Salnikov had taken down the last of Goodell’s three world records in the 400 free at a dual meet in 1979 and lowered it three times, though Canadian Peter Szmidt held it entering the Moscow Games (he didn’t compete, more collateral boycott damage). Goodell’s world record in the 1,500, the first man to break 15:10 with a 15:06.66 at the ‘76 Trials, still held from the final in Montreal (15:02.40). Spicing the mixture in 1980 was the pursuit of history: Both men were trying to be the first to break 15 minutes, a goal Goodell had long sought.

They hadn’t been at a major meet together since the Montreal Games, with an illness keeping Goodell out of the 1978 World Championships, where Salnikov did the 400-1,500 free double. But they’d encountered each other at dual meets between the U.S. and Soviet Union (and the East German women). Salnikov even trained with Goodell at Mission Viejo, in Mark Schubert’s famed “Animal Lane,” for a few stints.

“From where I was in my career, I was bigger, I was stronger, I had more experience,” Goodell said.

“I felt pretty good about my chances, and I had raced against him several times and I had always beaten him.”

In 1978, Salnikov, who as a teenager in 1976 had finished 5th in the Montreal 1976 final on 15:29, won in dominant fashion the World titles over both the 400m (3:51.94) , ahead of Jeff Float and Bobby Hackett, and 1500m (15:03.99), with Hackett third. Goodell was not present. Then, once the boycott guillotine fell, the 1976 Olympic champion didn’t have it in him to crank out the mega-distance yardage any more. He’s admitted to depression that descended in the aftermath. Seeing Salnikov take down the mark in Moscow, going 14:58.27 as part of the 400-1,500 double, was the last snap of the elastic.

“I just couldn’t train,” Goodell said.

“I couldn’t get up in the morning, I couldn’t get to sleep at night. I had a really difficult time.”

Four years on from Moscow, Salnikov missing the Los Angeles Games of ’84 through a Soviet boycott returned, Michael O’Brien claimed the 1500m crown in 15:05, slower than the 1976 podium. That remains the last American victory over the longest race in the Olympic pool.

Goodell doesn’t reserve any warm feelings for how the USOC handled the boycott, a sentiment in which he’s hardly alone. Back then, with the USOC taking a fundamentalist stance on amateurism, there was no pathway to post-grad swimming. Goodell, a 1981 graduate of UCLA, knew that the 1980 Games were his last shot at the Olympics, in an age where many elite swimmers only got one Olympics. The boycott ended his career prematurely.

The attempts of USA Swimming to mollify swimmers that summer landed flat, just as most efforts after the fact have. The boycott decision was rendered in April, and while hope persisted that it could be overturned in the summer, the USOC vote was more or less the death knell.

So USA Swimming conspired to reschedule Olympic trials for the week after the Games, a combined trials/nationals. The stated reason was to give the Americans, in absentia, a chance to one-up the Moscow times. Instead, for people like Goodell, it was a double-blow, unable to enjoy a win if it didn’t top the Olympic time, even though the setting in Irvine felt light years away from the Olympics.

“It was the biggest bummer in the whole fricking world,” Goodell said. “Who wants to swim under those circumstances?”

Goodell had long since begged off his heaviest training. When Schubert approached him that summer about still pursuing the 15-minute mark, Goodell had to admit to his coach that his heart wasn’t in it. “It was just a bummer,” he said. “Everything was a bummer.”

As if that wasn’t enough, Goodell endured a bout of food poisoning at Trials. He set an American record in the 800 free on the first night of the competition, the first American to break eight minutes (7:59.66) after Salnikov had clocked the first global sub-8minute in 7:56.49 the year before. But he slumped to second in the 400 free behind Mike Bruner and dropped to fifth in the 1,500 in 15:34.75, a far cry from the heights of Montreal.

While the round anniversary might have inspired some outside the forgotten Olympians to remember, it hasn’t done much for Goodell. There have been misfires in recognition before, from the hastily prepared medals presented to the Olympians in 1980 that took more than 20 years to actually be recorded as official Congressional medals. USOPC CEO Sarah Hirshland released a letter honoring the 1980 Olympians, and the members of the team got special letters and a commemorative pin.

Not of it means much to Goodell. He’s especially short on patience for the notion that Olympic governing bodies, those that used he and fellow athletes for political purposes, are suddenly disavowing individual athletes’ ability to use events like the Olympics for their own political means in terms of personal displays.

“I think that’s absurd that athletes can’t use their platform to voice their concerns about whatever their concerns are,” Goodell said.

“Absolutely insane. Look what they’re doing in the NBA and the NFL, taking a knee and all that bullshit. People want to say what they want to say. They’re stupid if they think they’re going to hurt their marketability, in my opinion, but more power to you if that’s what you want to do. And now they’re [Olympic authorities] saying they can’t do that? Even now, they’re wearing branding on their clothing and they’re being branded by all these companies and the USOC is making money off it and the athletes still have to toe the line and not have an opinion. It’s stupid, in my opinion.”

Love these old stories.

I agree 100% with you, Michael. LOVE the inside scoop.

Worth mentioning that Salnikov had already clocked 15:03.99 to win the world championships in 1978, by almost 17 seconds and only 1.6 off Goodells mark.

It is mentioned, Alberto… 1978 world championships.