Favourite Pools: Craig Lord On The Stadio Olimpico del Nuoto At The Foro Italico In Rome

Commentary

Favourite Pools. What are yours? As the swimming-less summer of 2020 draws on, the team at Swimming World will take a look at some of the great pools we love the most, why and what makes them so special. We’d like you to join in the fun and memories with your own suggestions, either by leaving a comment or sending us a picture you took of the venue you’ve chosen along with up to 300 words on why the place is one of your favourites: editorial@swimmingworld.com

Rome. Unusually quiet these days in a time of sorrow and sacrifice. The Eternal City has survived much down the years and will emerge from this crisis, too. I look forward to the moment I can once more skirt the Vatican, saunter past the Castel Sant’Angelo and wander over the St. Angelo Bridge just for the love of it and all the angles of Rome. Originally the Aelian Bridge or Pons Aelius, it was completed in 134 AD “by the Roman Emperor Hadrian“, they say, though I doubt he had much to do with it beyond orders and expectations.

Castel Sant’Angelo and the St. Angelo Bridge – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

Much water under a beautiful bridge that spans the Tiber and from there you can wend your way along the flow north to the Foro Italico, crossing at various other points at will and wish.

Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

Rome is a city to walk in and through, every corner and turn in street a step back into the future that plunges you into the past. Within an hour of St. Angelo on foot, the Stadio Olympic del Nuoto comes into view.

The Foro Italico sports complex is built on the slopes of Monte Mario. It was built between 1928 and 1938 as the Foro Mussolini on the cusp of the dictator plunging Italy into its darkest hour. The designers were Enrico Del Debbio and, later, Luigi Moretti, and their design was inspired by the Roman forums of the imperial age.

Built as a bid to get the Olympic Games of 1940 staged in Rome, the Foro would not see Olympic action for another 20 years. The racing pool we know today was built for the 1960 Olympics. It was inaugurated in 1959, Del Debbio joined by Aniballe Vitellozzi as lead designers for a complex that would host swimming, diving, water polo, and swimming part of the modern pentathlon events at Rome 1960.

It is very high up on my list of Favourite Pools.

Down the years, the venue has hosted the European Championships, 1983, and the World Championships, first in 1994 and then again in 2009 at a circus of shiny suits that let Rome, Italy and swimming down. The roar from the crowd in Rome was tremendous, though that for the swimming never quite matched that for the fabulous Bruce Springsteen concert over in the stadium on the eve of the championships.

While there were many terrific stories to write in Rome, the moment tarnished swimming in ways that still cost the sport to this day: as the count of world records sailed past 20 in a few days, I recall one newspaper editor saying “what a complete farce …”. Coverage of the sport in key outlets, including international agencies (some who made a policy around that time of dropping coverage of short-course swimming altogether when it came to having to make financial cuts and judging those on the ‘seriousness’ of sports and a general feel for how that seriousness could be weighed in money and governance) has been in decline ever since.

Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

A wonderful moment, then, in late summer 2017 when Konstantin Grigorishin and his International Swimming League, chose Rome for the Energy For Swim Champions for Charity at the start of setting a new tone and culture in the sport and on the way to the birth of Pro-Team swimming. The ISL celebrated its first season in 2019 and, coronavirus pandemic allowing, will further its revolution with a Solidarity Camp later in the year, the first regular wages ever paid to swimmers by an event organiser part of the mix.

The Tiber as guide, arrival at the the Stadio Olimpico del Nuoto sets a mood for the moment: its a serene place when still and a thrilling place when the lights go on, the crowd takes its place and the swimmers take their marks, an aquatic arena with a spark of setting fit to light the torches of Rome.

Gallery: The Stadio Del Nuoto & Scenes Of Rome

I’ve visited the place dozens of times in the past four decades. Like the city about it, the pool never tires. Below are some contemporary, edited extracts of memories from a few of those visits in my archive:

Rome Revisited

1990 – Retracing The Steps Of A Champion’s Golden Hour

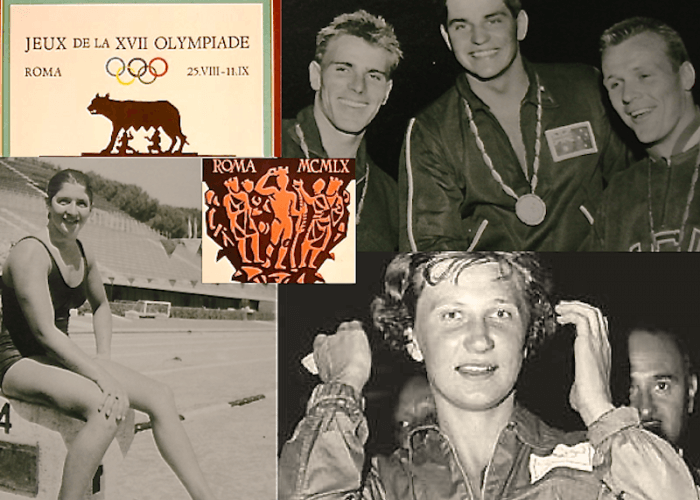

Rome 1960 – clockwise from top right: Murray Rose, John Konrads, George Breen; Anita Lonsbrough and Dawn Fraser – Images courtesy of: ISHOF, NT Archive and BBC still

When Anita Lonsbrough raced to gold ahead of Germans Wiltrud Urselmann and Barbara Goebel in the 200 metres breaststroke at the Foro Italico in Rome in 1960, she took time off work to do so. The result was gold for her and Britain – and a pay cut.

Lonsbrough worked as a clerk at Huddersfield Council at the time. The amateur era meant just that: swimming and Olympic gold had nothing to do with work – and her wages were docked for those days she wasn’t able to show up in the office. She was 19, the same age as Rebecca Adlington was when she became the first British woman in the pool since Lonsbrough to claim gold at Beijing 2008: wait 48 years and two come at once.

No lottery, no sponsorship in Lonsbrough’s day – and the minute the swimming ended, it was straight back home to work. For the class of 1960, savouring the Olympic experience had nothing to do with getting round to see as many sports as possible and visiting the merchandisers, marketeers and a multitude of other distractions for the modern athlete. For Lonsbrough, it meant keeping alive the memories of a day that transformed her life.

The tunnel between pools at the Stadio del Nuoto in Rome – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

Thirty years on from that golden day in 1960, Lonsbrough returned to Rome as a journalist covering the city’s Seven Hills International. Retracing the steps she took on her way to glory, we walked the length of the tunnel that connects indoor and outdoor pools.

Back in 1960, warm-up was in the original pool with its stunning mosaics on wall and deck. The swimmers gathered one floor down near the changing rooms before walking a corridor or marble titles and then the length of the tunnel into the lights and the roar that greeted the finalists to their blocks. Lonsbrough recalled:

“It was magical. The crowd was electric and I knew exactly where my mother was sitting. It still makes me tingle to think about it.”

A Commonwealth champion in 1958, Lonsbrough was a Commonwealth champion before she’d won a national title. Pools back then were not like they are now (even the Olympic pool in Rome, which has had a few major renovations down the years but lost none of its charm).

Lonsbrough arrived at a pool in Waalwijk in the Netherlands in July 1959, saw the murkiness of the water (and was sure she had seen a frog) and resolved to swim “as hard as I could so I could get out as quickly as possible”. The world record fell to her in 2min 50.3sec. That off the back of four to five sessions a week and training in gyms where the most sophisticated technology was often a mat and a medicine ball. Sport was a hobby, coaching was part-time and sports science was yet to be discovered. A good steak was the beef of champions.

Photo Courtesy:

In June, 1960, Urselmann clipped the world mark to 2:50.2 in Aachen, Germany. The Games were held in Rome in September. Everything to race for. Said Lonsbrough looking back:

“It was so thrilling. Travel had an exotic feel and Rome was a glamorous city. We were on top of the world.”

Out of the dive, Urselmann charged ahead, turning first at the 100 metres in 1min 20.2sec – her best 100 metres was 1:19.1. More prudent was Lonsbrough’s split of 1:22.0, with Den Haan and Goebel, of East Germany, on 1:22.9.

Lonsbrough summoned her strength and believed that gold was within her grasp. Down the third length, she clawed back the deficit to Urselmann but the West German was still in the lead with some 15 metres to go, when the pride of Yorkshire sped by. Urselmann was not done yet. As Lonsbrough’s stroke shortened, the German sensed a second chance and began to surge forward. Too late.

Lonsbrough had covered the second half of the race in 1:27.3, to Urselmann’s 1:29.8, and as well as the gold medal, Lonsbrough had taken back the World record, in the first sub 2:50, a 2:49.50.

A Pioneer For Her Sport And Women

Anita Lonsbrough – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

Lonsbrough was back in England within days of her triumph. Life had changed. She was invited as a special guest of honour to a Test match (cricket) and in 1962 became the first woman to win the BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

She swam on until the 1964 Games but abandoned breaststroke in favour of the medley, which made its debut in Tokyo. Lonsbrough was the first woman to carry the flag for Britain at the opening ceremony. As she remembers the moment, tears well in her eyes:

“As we approached the stadium you could hear the cheers from the crowds but walking through the tunnel it went very quiet and dark but then suddenly as we entered on to the track there was brightness and a deafening cheer. I almost felt I wanted to run back.”

She did no such thing, of course, and over the course of the Games, she met and fell in love with Hugh Porter, a world champion cyclist. They later married and were there in Beijing to witness the moment Adlington took a huge weight off Lonsbrough’s shoulders.

The scoreboard at the Water Cube confirmed the unexpected win. Adlington had been considered a “hope” in the 800m but this was the 400m freestyle: Britain, gold and bronze, to Joanne Jackson, America’s World medley champion Katie Hoff in the middle of them.

The British drought is over, 48 years after Lonsbrough’s gold, I spent the first few moments after the race putting out a short, straight take on events:

Rebecca Adlington, of Nottingham, became the first British woman to win an Olympic crown in the pool since 1960 when she claimed victory in the 400m freestyle here at the Water Cube in Beijing. The gold medal was Adlington’s in 4mins 03.22sec, 0.07sec ahead of Katie Hoff, off the USA, with Britain teammate Joanne Jackson third only 0.23sec further back. In their wake in what for the British pair was a brilliantly tactical effort, the reigning Olympic champion and world champion Laure Manaudou, of France, and the current world record holder, Federica Pellegrini.

The last woman to win a gold medal in the pool for Britain was Anita Lonsbrough in 1960. As two Union Flags rose to the rafters for the first time since Sarah Hardcastle and June Croft took silver and bronze at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles in the very same event, champions old and new could not hide their emotions.

There was the mixed zone to get to and then more writing and the medals ceremony to celebrate. I stood next to Lonsbrough, as I had on many occasions for almost 20 years as journalists on swim tour, and then wrote:

From the media stands, Lonsbrough stood tall for the national anthem, her lip trembling, the tears trickling down her cheek just as they had 48 years ago at Stadio Olimpico del Nuoto in Rome after she claimed gold in the 200m breaststroke. Since then, silver has been the best of British women and since 1984 only two British women have managed to make it to an individual final in Olympic waters. Lonsbrough said:

“I’m absolutely delighted. It’s been too long coming.”

The Water Cube – Photo Courtesy: Li Yong

Adlington is only 19 but she was very aware of where her success fit in the gulf of British swimming history. “Yes, 1960! It hasn’t sunk in yet. I’m over the moon!” She looked forward to catching up with the 1960 champion to share notes after the tour of warm-down pool, doping control, lunch and rest in readiness for Wednesday, when the new Olympic champion will attempt to back up by racing towards a second medal and possible gold, in her better event, the 800m freestyle. No British woman has ever won more than one gold medal. [That would change a few days later].

Said Lonsbrough, through tears and laughter: “It’s like a weight has just lifted off my shoulders. Every meet since Rome, every event and awards ceremony, year after year, I’ve been asked about ‘being the last British woman…’ Well, they don’t need to ask me any more! They can ask me something else – that’ll be nice.”

That was the last games at which we would sit together as colleagues but the conversations and laughter we shared down the years, her memories of Pat Besford, the late doyenne of swimming journalism, and much more, ring on in mind and memory and will be cherished until my days are done.

Rome 2009 – A Shiny Suit Circus

Fear not! I won’t trouble you with my vast back-catalogue of campaigning prose and vent on the shiny suits that had to be sunk (and sunk they were) if ‘swimming’ was to survive (it did). But here’s one aspect of my daily coverage from Rome World Championships in 2009: the only medals table I ran was one pertaining to suits, since they were so heavily responsible for outcomes far and wide.

Here’s a summary note from the last day of a meet at which that famous tunnel from the Lonsbrough story above was used as a bazaar. Once used to walk champions to their blocks, the tunnel was where swimmers without sponsors nor money enough nor access to shiny suits that would improve their ability to compete and significantly boost their chances of setting national and other records would now line up at small stalls and wait in temperatures often exceeding 40C in the height of a Roman summer. Their goal: to get hold of a suit as suits were handed back in by other swimmers forced to rent their non-textile equipment by the swim.

At the Rome 2009 world championships, the 13th of their kind organised by FINA, the international swimming federation, since Belgrade in 1973, most swimmers were given freedom of choice as to which suit to wear. Their choices had little to do with brand loyalty in many cases, though some swimmers did prize loyalty, be that through choice or financial expediency.

The winner of suit wars was arena, its X-Glide having sped swimmers to 14 gold, 12 silver and 10 bronze and 13 world records

Rome 2009 was about doing whatever it takes before the sport of swimming is revived in 2010.

The Rome 2009 Suit Wars medals table and the world-record count among the suit makers:

A form of progress that lost its shine – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

SHINY MEDALS TABLE (no relays)

- X: 14 12 10 (36)

- J: 9 12 16 (37)

- L: 6 2 7 (15)

- H: 4 6 1 (11)

- D: 1 2 1 (5)

- One extra bronze, joint 3rd 200m breaststroke, men

WORLD-RECORD BONUS – solo swims only (quartets too mixed up)

- X: 13

- J: 13

- H: 7

- L: 5

- D: 1

- Unknown so far = 4, two suspected to be X suits

KEY: J = Jaked01; X = arena X-Glide; H = adidas Hydrofoil; L = Speedo LZR; D = Descente Aquaforce

Rome 1960 – From The Craig Lord Archive

More than half a century on – the Pool at the Foro Italico in Rome – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

This summer will mark the 60th anniversary of swimming at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome: 45 nations sent swimmers and the medals table was topped by the USA, with 8 gold and 3 each of the other two colours; Australia followed with 5, 4, 3 and Great Britain made the top 3 with 1 medal of each colour.

Washed away by Australia in 1956, American gladiators fought back in Rome. No nation would top the USA again in Olympic waters until 1988, when GDR women won 11 gold medals, buoyed by State Plan 14:25 and the assisted means of Oral Turinabol and more on the cusp of the end of another era, the wind of political change about to blow the Berlin Wall down.

Australian men got the better of their American rivals by one gold medal in Rome – and it was one gold medal with Australia first and the USA second that caused one of the biggest controversies of the Games. American women dominated, with five gold medals out of seven. For the first time since 1908, Britain finished among the top three nations on the medal table and the only solo world record to fall among women, courtesy of Anita Lonsbrough in the 200m breaststroke.

The Foro Italico – later to stage the 1994 and 2009 World Championships – contained two pools connected by a hidden tunnel, from which swimmers emerged in dramatic, gladiatorial style to walk out for their races. The indoor facility provided an ideal training facility, while the outdoor competition pool came complete with the first “wave-breaker” plasticised lane dividers. The addition of butterfly in 1956 led to the introduction of 4x100m medley relays for men and women in Rome, taking to 15 the number of finals, eight of those for men. Of the 45 nations represented, 42 sent men and 26 sent women. Swimmers from Malta, Puerto Rico, Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe) and Turkey, celebrating its first four wins in global waters at the world junior championships this year, were seen for the first time.

At the helm of the men, Murray Rose (AUS) became the first man to retain the 400m freestyle title and teammate David Theile became the first in 36 years to retain the 100m backstroke title.

Dawn Fraser (AUS) claimed the most decisive 100m freestyle victory at the dawn of modern Olympic history, 1.6sec ahead of the most successful woman of the Games, Christine Von Saltza (USA), who took three golds, her victories unfolding in the 400m freestyle and in two American world-record-breaking relays. If Fraser dominated, the men’s 100m freestyle belonged to the other end of the spectrum of tightness, the decision of judges setting in motion a wave of controversy that would roll on through the years.

The 100m Free Final That Accelerated The Age Of Electronic Timing

John Devitt (AUS) was the last swimmer to win an Olympic gold medal in the pool where the human eye was judged preferable to manual timing and the first electronic device that registered manual times to a hundredth of a second.

John Devitt (AUS) was the last swimmer to win an Olympic gold medal in the pool where the human eye was judged preferable to manual timing and the first electronic device that registered manual times to a hundredth of a second.

He entered the Rome 100m showdown as world record holder and 1956 silver medal winner. Third at the turn, Devitt took the lead at 70m and looked like the sure winner. But in the closing metres Lance Larson (USA) surged: there was nothing in it at the touch.

Three judges went with the Australian, three with the American, while the clock favoured the American, on 55.0, 55.1 and 55.1 to the Australian’s 55.2, 55.2, 55.2. Some references describe the use of an electronic-timing device but the machine that was used was electronic only in the sense of relaying the data to a printer and recording times to a hundredth of a second. The times registered on the device were in fact manual, the result of an official pressing a button on sight of a swimmer touching the wall, in the same way that a timekeeper stops a hand-held watch.

That electronic readout also had Larson ahead, 55.10 to 55.16. Despite all that evidence, German Hans Runstromer, the chief judge who, under FINA rules had no say in the matter, instructed recorders to change Larson’s time to 55.2 and to grant gold to Devitt. Four years of protests failed to overturn the decision.

The controversy did no harm at all to the work of those looking to a future in which swimming times would be recorded by automatic timing systems:

A clearer view of the Rome 1960 final. Devitt ended his career with two golds (100m, 1960; 4x200m 1956) a silver (100m, 1956) and a bronze (4x200m, 1960), and four individual and 10 relay world records to his credit. Oddly, he did not race the freestyle leg of the Australian medley quartet that claimed silver in Rome behind a US quarter that included Larson and broke the world record.

Training Under the Boardwalk

Talking in 1996 to one of the world’s leading authors on swimming in his day, Cecil Colwin, now deceased, Devitt recalled the way they trained back in the old days. “At White Bay power station, on Sydney Harbour, there was a stretch of water under the wharf that provided a square ‘swimming course,’ and this is where ‘Coach Tom’ decided we would train; ‘under the boardwalk,’ as you might say, hidden from sight,” said Devitt.

Talking in 1996 to one of the world’s leading authors on swimming in his day, Cecil Colwin, now deceased, Devitt recalled the way they trained back in the old days. “At White Bay power station, on Sydney Harbour, there was a stretch of water under the wharf that provided a square ‘swimming course,’ and this is where ‘Coach Tom’ decided we would train; ‘under the boardwalk,’ as you might say, hidden from sight,” said Devitt.

Training under the wharf, in the mostly heated, swift-flowing water from the White Bay power station, helped Devitt and his training partners to swim year-round in what were then good conditions and at a time when great facilities were much harder to come by.

Barnacles and oysters flourished in the ‘heated’ seawater. For protection, the swimmers wore shoes when swimming. Devitt told Colwin: “The only suitable shoes available in those days were sand shoes, which allowed us to tread safely on the bottom. The shoes filled up with water and became heavy, hence I developed the sort of ‘2-beat Australian kick’ that stayed with me throughout my career.”

The pier – how it looked in 1996, courtesy of Cecil Colwin and Nick Thierry

When not sprinting, the swimmers swam around the perimeter of the water course, one square lap equalling 400m. The current flowed into the course at right angles, each side of the square offered a different experience, with and against a flow that changed pace according to how many turbines were being used in the power station.

Occasionally, Devitt told Colwin, the turbines would stop and the water temperature would drop from pleasant to 15C cooler: shock and cramps ensued.

Devitt said, “The current enabled us to develop strength and power, and, as we grew older, we took advantage of the speed of the current to learn pace judgement.

“We knew just how fast the current was moving and how long we could stay in a particular spot while swimming against the current.

“We continued swimming these 400 metre ‘laps’ until we were thankful to hear the coach call a halt. This routine provided quite a good workout. Some of us called it ‘square bashing’.”

Square Bashing to sprinting with the flow & learning fast turns

“As if square bashing wasn’t enough to keep us fit,” added Devitt, “Tom Penny, always innovative, discovered a canal on the other side of the power station, about 20 metres wide, through which a strong current flowed in one direction. Penny quickly noted that the canal provided the potential for about 120 metres of continuous swimming.

“We knew our coach well, and so we weren’t too surprised when he decided that it would be a good idea for us to swim directly into the current. He didn’t call these ‘effort swims,’ but he would have been considered ahead of his time had he done so.

“After we had swum up against the current in the 120 metres course, we would drift back in its flow to the starting point, all the time practising tumble-turn somersaults on the barnacled walls of the canal. This routine helped us to develop a fast approach into the turn, when actually turning in a proper swimming pool. In this way, we used our time in the water to best effect.”

When Konrads Stepped Up To Take Rose’s Crown

In Rome in 1960, Devitt claimed silver in the 4x200m relay alongside John Konrads, world record holder over 400m but third behind Rose and Tsuyoshi Yamanaka (JPN). The 1,500m was a different story.

Coached by Don Talbot, Konrads took up swimming on medical advice given to his parents after their son contracted a mild case of polio. Between January 11, 1953 and February 27, 1960, the son of Latvian immigrants set 11 world records over 200m (2), 400m (4), 800m (3) and 1,500m (2).

Four days later, after a disappointing 400m in which he finished third and kept bronze after a protest from Britain over Ian Black’s claim to having finish third was dismissed, Konrads delivered over 30 laps, racing tactically on the shoulder of George Breen (USA) until the 1,100m turn, after which he pulled away – taking Rose with him – to a 17:19.6 Olympic record 2.1sec ahead of his teammate, with Breen earning bronze.

Talbot’s autobiography “Nothing but the Best”, relates the coaches version of events in try Talbot style – and then relate the memory of the swimmer who backed up the story in words that showed just what the coaching had brought:

“When you performed badly it wasn’t a pleasant experience to go back to the coach. And I knew I had performed badly. I didn’t understand all the reasons why. But, after the medial ceremony he pulled me aside and said ‘tough luck mate. Now for the 1500 on Friday night’. He just cut off the past in three words and started building my vision of the future, which was the 1500.”

Upsets and Record Runs

William Mulliken (USA) produced the upset of the Games when he won the first 200m breaststroke final since the underwater swimming that gave Masaru Furukawa (JPN) victory in 1956, was banned. Mullikan’s time of 2:37.4, 0.6sec ahead of Yoshihiko Osaki (JPN), was 0.2sec slower than a heats time that established an Olympic record under the new rules, and 2.5sec slower than Furukawa’s underwater effort.

Terry Gathercole, a future head of Swimming Australia, held the world record at 2:36.5 but finished 6th and 3.7sec off his best. Mullikan, coached by Raymond Ray and the first American to win the title since 1924, went on to become a lawyer in Chicago. Behind him for bronze in Rome was Wieger Mensonides, who remains the only Dutchman to have ever won an Olympic medal on breaststroke.

In the year before Rome, Michael Troy (USA) broke the 200m butterfly world record five times, crunching the mark from 2:19.0 to 2:13.2. His Olympic victory of 2:12.8, a world record on this day 55 years ago, came as no surprise and left him 1.8sec ahead of Neville Hayes (AUS). Back in sixth was a young Kevin Berry (AUS), the 1964 champion in the making.

Troy, coached by James “Doc” Counsilman, collected a second gold medal alongside George Harrison, Richard Blick and Jeff Farrell as a member of the USA 4x200m quartet that set a world record of 8:10.2.

Troy, a Naval officer who was decorated for “heroic action” in Vietnam, later worked in real estate in San Diego and coached Michael Stamm to Olympic silver medals (1972) on backstroke behind the dominant backstroke swimmer from 1967 to 1973, Roland Matthes, of East Germany.

These were the days when races ended at a ribbon strung across the pool shy of the end wall beyond the 220-yard mark in this U.S. national-title race a year after Troy’s Olympic win that tells us much about the early journey of butterfly technique on its way to the smoothness of speed we know today:

Farrell, meanwhile, also took gold in the inaugural medley relay alongside Frank McKinney, Paul Hait and Lance Larson, their world record of 4:05.4 leaving them 6.6sec ahead of an Australian quartet that included Theile and Gathercole.

Fraser (AUS) crushed Christine Von Saltza (USA) over 100m but succumbed to the 16-year-old American three times. Beyond being a member of the winning freestyle and medley relays that produced world records of 4:08.9 and 4:41.1 respectively, Von Saltza claimed gold over 400m freestyle in 4:50.6 (Olympic record) and 3.3sec ahead of Jane Cederqvist, the only Swedish swimmer ever to win an Olympic medal in the event and the first woman to break 10mins over 800m at a time when 400m was the Olympic limit for women.

The final also saw Ilsa Konrads (AUS), who held world records over 440yd (1) 800m (4) and 1,500m (1), finish fourth and Fraser fifth. Von Saltza, who ended an Australian run on the 400m world record when she clocked 4:44.5 at the US trials on the eve of the Games in Rome, also held the world record over 200m backstroke.

In 1961, Von Saltza retired at 17 to enter Stanford, where she read Asian history. Half-way through, she took a leave of absence and coached swimming across Asia. After serving as an assistant chaperone-coach for the USA women’s team in 1968, she spent 25 years as a programming engineer for IBM.

The 100m backstroke title went to Lynn Burke (USA) in an Olympic record of 1:09.3, just 0.1sec shy of her own global mark. Coached by George Haines, Burke was the first American woman to win the title since 1932. She later became a model in New York, an author, business woman, and mother to three children.

The only solo world record, a 2:49.5 over 200m breaststroke, fell at the hands of Anita Lonsbrough (GBR), a 19-year-old clerk at Huddersfield Corporation in Yorkshire who had her wages docked for taking time off for training and travel. In Rome, Lonsbrough slept for 12 hours before a final that she won by 0.5sec over Wiltrud Urselmann (GER). After her racing days were done, Lonsbrough worked as a swimming journalist, for a British newspaper and BBC Radio, her swansong world titles Rome 2009.

The Tale of Mrs. Thurlow

![Faith Leech, right, with Dawn Fraser and Lorraine Crapp [courtesy: ES Archive]](http://www.swimvortex.com/wp-content/uploads/FaithleechDawnFraserLorrainecrappbio-250x159.jpg)

Faith Leech, right, with Dawn Fraser and Lorraine Crapp, centre [courtesy: ES Archive]

Between January 1956 and the eve of the Olympic Games late that year in Melbourne, Crapp established a phenomenal seven world records in the 100m (2), 200m (2), 400m (2), and 800m (1). Of those standards the 400m set her apart in the history of distance freestyle as the first woman to race inside 5 minutes. She did so by a massive margin: first on 4:50.8 and then, on the eve of the Games, clocked 4:47.2. At the 1956 Games, she finished a close second to Fraser in the 100m and won the 400m in 4:54.6, 7.9sec ahead of Fraser. She won a second gold medal as a member of the world-record breaking (4:17.1) 4x100m freestyle quartet. She might have gone down as the first woman to win four gold medals at one Games had there been a 200m and an 800m event for women in the Olympics in those days.

Crapp had a rhythmic, free-flowing, well-coordinated freestyle that was described as “poetry in motion”. Her coach, Guthrie, also coached coaches, Harry Gallagher and Don Talbot among his protégés. Guthrie was an innovator who pioneered the application of interval training introduced by sports scientist Professor Frank Cotton and took the calisthenics dry land training methods of Bob Kiphuth (USA) to the next step by using pulley weight machines. Her status is world swimming well established, there was a new line in her story as she headed to the Rome 1960 Games: on the eve of departure for Italy, she secretly married team doctor Bill Thurlow.

Thurlow travelled apart from the team and stayed in a rented apartment in Rome. After lights-out in the Olympic Village, Mrs Thurlow would tip-toe out and join her husband. When Australian officials found out, they put a curb on her movements, even though other married athletes had been allowed to stay with partners outside the village.

Demoralised, she raced well below best and lost 2.7sec to Carolyn Wood (USA) in the 4x100m freestyle. The USA took the title in a world record 2.4sec ahead of Australia. Subsequent to her retirement, the Thurlows won first prize in one of the Sydney Opera House Lotteries. Crapp was one of the eight flag-bearers of the Olympic Flag at the opening ceremony of the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

The End of an Era

Rome marked the end of an era, Tokyo 1964 the start of a new one, the birth of medley in the mix of a bigger program in the Olympic pool.

In Tokyo, the programme would grow to 18 events, 10 of those for men. The price of adding a 200m backstroke, a 400m medley and a 4x100m freestyle relay to the men’s programme was the loss of the 100m backstroke. For women, the 400m medley was the only new event.

The Tokyo Games, the first to be fully televised, also witnessed the first automatic timing system seen at the Olympics.

What new line in the book of firsts will Tokyo 2020, now in 2021, write?

Do you have a favourite pool and venue and memories to share. Let us know in comments or by sending us 300 words or so and at least one picture from your archive (noting the source): editorial@swimmingworld.com

- All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine, the International Swimming Hall of Fame, nor its staff.

Great read and swimming history one not likely to get anywhere else.

Loos in Farmer’s Branch. It was awesome seeing your name using colored light bulbs on scoreboard and two 25 TD pools with bulkheads. Thought I was big time.

Nostalgia for me. FOOTHILL JC POOL in LOS ALTOS CALIFORNIA

Where I broke my first National record in 1964 also the first I believe 50 meter/25 yd pool in Northern California

Jeff, Jenny, Pablo, and Janet were drying off away from camera

Hard to be my local Des Moines, IA YMCA pool…

North Sydney Pool. No other words required!

Les Hopkins loved swimming in that pool, for various reasons ?

At one stage there were more World Records broken in this pool than any other in the World

Great article.

Although the first thing which comes to my mind is the doped Chinese women’s team, which almost caused Krisztina Egerszegi to retire – good she didn’t

Thanks Kim. Yes, the place is haunted by the things that tainted what would and could and should have been amazing showcase for swimming but ultimately tainted it, 1994 and 2009 for different reasons.