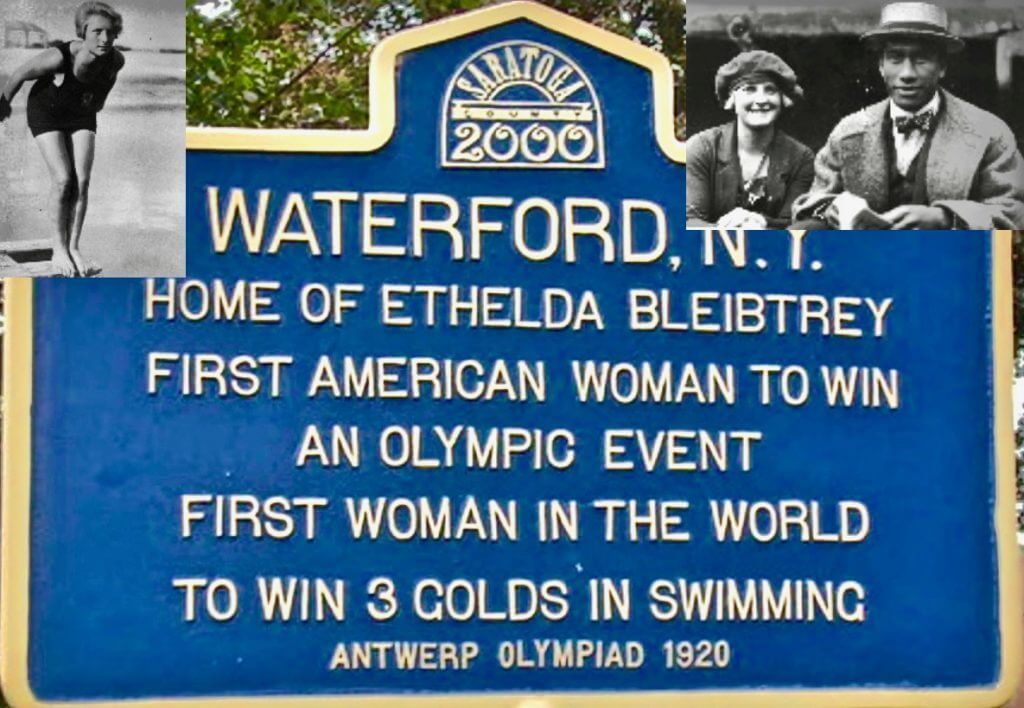

Ethelda Bleibtrey’s Pioneering World Record 100 Years Ago This Day

Ethelda Bleibtrey World Record: American Pioneer, 100-Year Anniversary

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the first women’s world record over 440 yards (later 400m) freestyle – and the first global standard set by Ethelda Bleibtrey. A year later, she would become the first American woman ever to claim Olympic gold in the pool – and the first women to claim three golds, too.

Over the 440 yards freestyle in New York on August 16, 1919, Bleibtrey set the first official world record over the distance, in 6mins 30.2sec. Since then 13 other Americans – in 31 efforts in total – have set the global standard over 440y and then 400m, the current standard 3:56.46, set by Katie Ledecky for Olympic gold in Rio de Janeiro on August 7, 2016.

In the same year Bleibtrey – born in Waterford, New York, on February 27, 1902 to John and Maggie Bleibtrey – swam her name into the record book, she made headlines and became a pioneer for women’s rights, too: at Manhattan Beach, Bleibtrey, who learned to swim on medical advice given to her because she suffered from polio, removed her stockings before wading in for a swim.

Her summons for “nude bathing” and indecency prompted a public outcry and the swimmer was freed from jail, while swimming was freed from stockings by a change in the law. Being paddy-wagoned down to the New York police station for a night in jail proved worthwhile: the Big Apple got its first big swimming pool in Central Park after Mayor Jimmy Walker intervened.

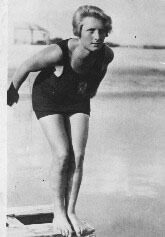

Ethelda Bleibtrey – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

Bleibtrey had carved herself a place in the pantheon before turning professional in 1922: she went down in history as the first American woman ever to claim Olympic gold in the pool, the first woman ever to claim three Olympic gold medals at one Games and the first to set five world records in the course of making three podiums.

Her first public display after turning professional led to a second arrest: she took a dip in Central Park’s reservoir in a campaign to force the city to build a pool there.

When Bleibtrey was asked to look back on her career in the 1960s, when Don Schollander (USA) became the first swimmer to win four gold medals at the same Games, she told the International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF):

“At that time, I was the world record holder in backstroke but they didn’t have women’s backstroke, only freestyle in those Olympics.”

Olympic Triple Gold

Time and events being what they were and are, Bleibtrey remains the only woman to have won every event open to her at an Olympic Games. In Antwerp 1920, the then 18-year-old set five world records, improving the global standard in both heats and finals of the 100m (1:14.4, confining Australia’s 1912 champion Fanny Durack’s 1:16.2 to history, and 1:13.6) and 300m freestyle (4:41.4 and 4:34.0), and helping the US 4x100m freestyle relay team to a 5.11.6 victory.

Ethelda Bleibtrey with the other hero of Antwerp 1920, USA teammate Duke Kahanamoku – Photo Courtesy: ISHOFPhoto Courtesy:

Bleibtrey went on to enjoy a glamourous life: she surfed with the Prince of Wales in Hawaii, dated oarsman Jack Kelly in Atlantic City, and went on a world tour, taking in the Panama Canal, Australia and New Zealand, her journey into Oceania at the behest and invitation of Australian pioneer Fanny Durack, the first Olympic swim champion among women in 1912. Coaching and swimming teaching became part of Bleibtrey’s life in New York and Atlantic City before she became a nurse in North Palm Beach, Florida.

Looking back at Antwerp, she recalled racing “in mud and not water”, the tidal estuary used for the Games, and participated in the first athletic sit-in when teammate Norman Ross organised a protest until the U.S. Olympic Committee provided a more classy style of travel for the team’s return home.

On the occasion of her induction in 1967, Bleibtrey told ISHOF:

“I have my memories and I guess some of those other people remember too. I owe a great deal to swimming and to Charlotte Boyle, who got me in swimming and L. deB. Handley, who coached me to the top.”

Bleibtrey passed away on May 6, 1978 in the summer that saw Kim Linehan, of the USA, hack the world 400m mark back to 4:07.66 three weeks before Australian Tracey Wickham clocked a stunning 4:06.28, a mark that stood as a World-Championship record until Laure Manaudou, of France, took the global crown in 4:02.61 at Melbourne 2007.

The Swimming Suffragettes

Women were granted access to the Olympic arena only eight years before Bleibtrey made her mark – and five years after the arrest of Australian Annette Kellerman at Revere Beach near Boston, USA, for ‘indecent exposure’ and the pioneers in the pool were moulded of the same defiant spirit.

Sarah Frances “Fanny” Durack was born to Irish parents in Sydney on October 27, 1889. She learned to swim in Sydney’s Coogee Baths using breaststroke, the only stroke open to women at the time. From 1906, she and friend and rival Mina Wylie dominated the scene – but it was their fight to get to Stockholm that set their stories apart.

While the men in charge of selecting the Australian team for 1912 declared it a waste of time and money to send women to Sweden, rules of the New South Wales Ladies’ Amateur Swimming Association declared that no women could compete at events where men were present. A public outcry resulted in a vote at the association that cleared the way for Durack and Wylie to make the journey to Europe – as long as they paid for themselves.

That vote sounded the death knell for the rule dictating segregation of the sexes and a successful appeal for funds contributed to Durack and Wylie’s passage to Stockholm and to the first gold and silver medals in the pool for women. Among the 27 debutantes in Stockholm were the first Olympic relay champions: in the 4x100m freestyle, Isabella Moore, Jennie Fletcher, Annie Speirs and Irene Steer gave Britain gold in a world record of 5:52.8.

Many years later, Fletcher told ISHOF:

“We swam only after working hours and they were 12 hours and six days a week. We were told bathing suits were shocking and indecent, and even when entering competition, we were covered with a floor-length cloak until we entered the water.”

After the Games, Durack and Wylie went on a ‘worlds tour’ to promote women’s swimming and were beaten by rivals using the ‘new American crawl’. Illness prevented Durack from defending her title in 1920.

Here’s a more recent take on what it was like in the day of Durack:

In Durack’s absence, Bleibtrey dominated the headlines – for her swimming and her spirit. Four years on from Antwerp, the Paris 1924 Olympic Games witnessed the emergence of Gertrude Ederle, who in 1919 had become the first official world record holder over 880yd, in 13:19.0. Disappointed with one gold and two bronze medals in Paris, she set herself a new challenge: crossing the English Channel.

Not only did Ederle become the first woman to achieve this feat, but she did so in a time almost two hours faster than the world record held by a man. Ederle then went on a world tour for six months in the company of Aileen Riggin, Olympic diving champion and the first woman to win Olympic medals both in the pool and off the boards at the same Games, at Paris in 1924. Riggin later became one of the first women sports journalists in the world. She died in 2001, aged 96. Ederle died in 2004, aged 98.

Beyond those who excelled in the pool, none were more important to the advancement of women’s rights than Charlotte Epstein, a New York City courtroom stenographer and ardent advocate for American women’s competitive swimming. Beyond being the woman who picked Ederle out from the pack when looking for a representative to swim the English Channel, Epstein played a large part in the expansion of swimming for women, both nationally and internationally, in the early twentieth century. At the FINA Congress in Paris, July 1924, Epstein was invited to advise on rules for ladies suits, her views contributing vastly to the emancipation of women.