Even Superheroes Lose

By Claire Alongi, Swimming World College Intern.

Sometimes, it seems like athletes might actually be superheroes. Our favorites seem to always be on the winning side – untouchable. From basketball players who soar over seven feet tall to athletes like Michael Phelps with the ideal physique for his sport, it seems like these stars exist in a class all on their own. Yet sometimes we are reminded that even those who seem invincible are humans too, just like the rest of us.

The World Aquatics Championships, hosted by FINA in Gwangju, South Korea, recently came to an end. So too did the reign of many legendary records. It’s both euphoric for the new swimmer being crowned world champion and humbling for the athlete passing on the title. But these moments are more complex than just that. They should make us reflect on what it means to win and lose. They provide a way to reflect on the history of the sport and what it takes to be the best.

What is Loss When it Comes to Swimming?

There is no definite delineation between where a loss ends and a win begins. In fact, the two may not be so opposite as they may seem.

It’s easy to define “losing” as not finishing first or adding a few seconds. If you aren’t first, you’re last – right? Well, not really. Losing doesn’t need to be such a bad thing. Losing means you have something to reach for, whether it’s a new time, breath count or a better breakout. And what might have seemed like a bad race may not have been that bad after all. Maybe you didn’t come in first, but you still got a best time.

It’s easy to interpret your efforts through a narrow lens of criticism and negativity, thinking in black and white terms. Everything you did seems like the biggest mistake ever. But sometimes you need to take a step back and see the bigger picture of not just your race but also your long-term development.

Celebration and Perspective

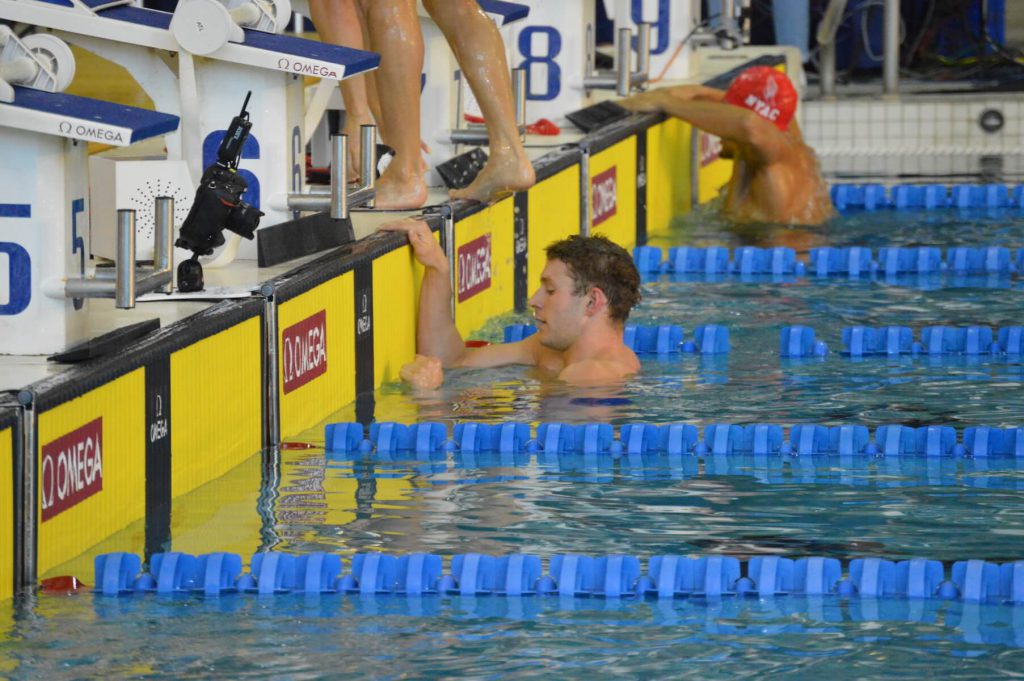

Regan Smith reacts – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

There were quite a handful of surprises in Gwangju this year. After Katie Ledecky‘s shocking defeat in the 400 free (though not beating Ledecky’s world record), teenager Ariarne Titmus led the Australian women to a new record in the 800 free relay with a time of 7:41.50. Another teenager, American Regan Smith, broke Missy Franklin’s 200m backstroke record from 2012 with a time of 2:03.35. Simone Manuel broke the American record in the 100m freestyle for women, all with a lane one seed. Phelps lost not one but two world records: one to Hungarian Kristóf Milák in the 200m fly and the other to Caeleb Dressel. Dressel broke Phelps’ 100m fly record that stood for a decade by swimming a lightning fast 49.50.

Looking back at the beginnings of our competitive sport, one of the first world records listed for the 100m fly was posted by György Tumpek of Hungary from 1957. He went a 1:03.4 – nearly 14 seconds slower than Dressel’s new record. Around the same time, Phillipa Gould set a record in the 200m backstroke of 2:39.9 – over half a minute slower than Smith’s new record. If someone had told Tumpek in 1957 that a day was coming when someone would break 50 seconds in the 100 fly, he likely would have expressed staggering disbelief. A similar reaction would come from explaining to Gould that the 200m back record would come close to breaking two minutes.

The Bigger Picture

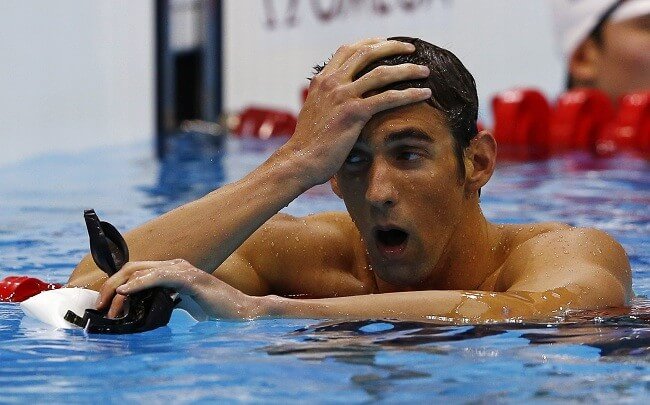

Photo Courtesy: PATRICK B. KRAEMER

Most people will never know what it’s like to win a world record, nor will they comprehend the time and effort it would take to get there. One can only assume that witnessing your own record broken by someone else is anywhere from downright painful to sickly bittersweet. But instead of seeing it as an individual loss, perhaps it’s time to re-frame it as a win for the sport: for human ability and strength as well as a moment to remember that professional athletes are not, in fact, superhuman.

In a Washington Post piece describing losing as it applies to youth sports, sports psychologist Caroline Silby says, “If parents get angry, blame unskilled players, or dwell on a loss, they ruin the whole point of being on a team: a sense of belonging. Athletes who have that feeling — that they are connected to something larger than themselves — are less stressed and have higher self-esteem.”

When people are pushed to the limit – whether by themselves or their parents – to be crafted into the superhuman Olympian they see on the news, they lose sight of the purpose and higher connection that sport can bring. The concept of an impenetrable super athlete is false: Parents and athletes are chasing something that doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean that losses should be tossed aside or dwelled on for too long. It does mean that people should think about their wins and losses critically to recognize that there’s much to learn (both good and bad) from a race.

When Losing Isn’t Really Losing

Photo Courtesy: Instagram, @missyfranklin88

Ledecky dropped out of several races in Gwangju due to illness. Last year, Franklin wrote a heartfelt letter announcing her retirement from swimming. She described retirement as not an end but a “new beginning.” At times, we see our heroes falter or walk away from the sport altogether. But by moving on or losing a race or a record, they are not becoming any less great. All those records – standing or broken – act as goalposts for the next person to race toward. They are what has propelled the sport to get faster and faster.

Being the best doesn’t mean being perfect. Humans aren’t perfect. Yes, even Olympic swimmers are imperfect, shocking as it may seem.

So to all the athletes out there representing their country or just jumping in the pool for summer league, remember to celebrate your wins. Don’t get bogged down in your losses. In a sense, they aren’t really losses at all.

-All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine nor its staff.

This is such an important message — and so beautifully written!

Really awesome article! Impressive writing and a nice, new perspective. Well done